Introduction

In the current globalised world, the attention directed towards the development of region-based tourism has gained significant momentum (Qu et al., 2023). This heightened focus is particularly pronounced in remote tourism destinations seeking greater visibility and prominence within the industry (Bjarnason, 2014, 2021). Certain insular and archipelagic locations are disrupting the market thanks to an increased public interest “in the environment and in tranquil, less developed areas such as coastal settings which are still pristine for tourism purposes” (Agius et al., 2021, p. 149). In this regard, Iceland stands as a dynamic insular destination characterised by a landscape shaped by frequent volcanic eruptions and natural calamities (Ágústsdóttir, 2015; Ólafsdóttir & Dowling, 2013; Sæþórsdóttir et al., 2019). Historically reliant on fisheries for sustenance and economic stability, the nation faced a profound economic downturn following the Great Recession of 2008. This downturn, marked by the devaluation of the Icelandic Króna (ISK) (Jóhannesson et al., 2010), paved the way for an incessant surge in tourism demand, leading to a significant national dependence on the tourism economy (Macheda & Nadalini, 2019). The enthusiastic influx of visitors, backed by robust governmental intervention for tourism development, resulted in a staggering fivefold increase in international arrivals between 2010 and 2017 (Gamma, 2018). Traditionally, Keflavík Airport (KEF) has served as Iceland’s primary international gateway handling approximately 98.5% of all international flight arrivals (Icelandic Tourist Board, 2019, 2023). Meanwhile, smaller airports like Akureyri Airport (AEY) and Reykjavik Airport (RKV) have predominantly facilitated domestic connections (isavia.is, 2022). However, national air travel underwent notable shifts in early 2022 when the airline company Niceair announced its intention to initiate international flights to and from AEY following runway expansion and the addition of an international gate at the airport. Despite its promising kick-start, the company faced insolvency within a year, prompting the competitor IcelandAir to announce a direct connection between KEF and AEY (IcelandAir, 2023). This manuscript advocates that airport expansion and consequent regional development entails negative as well as positive factors. Gössling and Higham (2021) highlight the evolving approach to global tourism development with heightened awareness among travellers, stakeholders, and policymakers regarding the adverse environmental impacts of air transport. A main limitation is that delving into the increasing airline traffic emissions is out of the scope of this research. The study aims to envision North Iceland’s imminent tourism development as an emerging insular destination with Akureyri serving as its pivotal transit hub and service centre.

Literature Review

The Never Ending Story of Perceived Destination Development

Academic discourse has persistently sought to define a tourism destination encompassing its development stages (Butler, 1980), performance dynamics (Haldrup & Larsen, 2009), and concurrent strategies for self-promotion (Lew, 2017). An emerging destination corresponds to an industrial district with a multi-scale group of characteristically homogeneous places conceived as micro destinations where the entire community is influenced by corporate decision-making strategies (Rodríguez & Raúl, 2018). Policymakers and stakeholders tend to give weight to the construction of ancillary elements like hospitality facilities and robust infrastructures as primary tools for the ultimate flourishment of the area (Laws, 1995; Mazzola et al., 2022). Howie (2003) further stresses that a destination is characterised by accommodations, primary services, and transport to and from different attractions. The ramifications of destination development extend beyond a mere open system catering to the destination itself including increased employability, improved infrastructure, and year-round tourism (Dalimunthe et al., 2020; Gamor & Mensah, 2021). Effective destinations are considered “amalgams of tourism products offering an integrated experience” where accessibility to the place, activities, events, and tailored customer services are available on-site (Buhalis, 2000, p. 2). The importance of developing products and services is also exacerbated by Anholt (2007) and Turok (2009), who emphasise the need for diversification in the burgeoning tourism sector on micro and macro economies. Pike et al. (2016) further underline the need for meticulous management strategies accompanying every product development, ensuring the potential long-term fostering of a strong tourism destination image. Analyses of tourism policies have underscored the potential positive and negative impacts on host communities, the latter often connected to mismanagement (Leiper, 2000). Ritchie and Crouch (2003) call for a strategic approach wherein destinations avert mismanagement by concurrently developing infrastructures and services, leveraging contemporary and progressive management strategies to favourably compete with more sustainably successful counterparts. The development of tourism destinations remains under scrutiny as questions about their ability to effectively address capacity management and regenerate existing resources persist (Santana et al., 2022). Capacity building could tackle critical capacity issues among the community (Moscardo, 2008). In this context, destination management organisations (DMOs) must cultivate human capacity, diversify approaches, and understand the perspectives on seasonality of tourism actors (Getz & Nilsson, 2004; Medina et al., 2022; Novelli, 2017). Innovative thinking and transitioning existing goods and services serve as essential assets to tackle seasonality issues and control incoming arrivals, particularly in peripheral and emerging destinations where product and market diversification wield significant influence (Pham et al., 2018). Wyckoff (2014, p. 2) exerts direct influence on creating “quality places” where people are inclined to live, learn, work, and engage in recreational activities.

Complexities to Breaking Seasonality

Seasonality is characterised as a “temporal imbalance” (Butler et al., 2001, p. 5) inherent in the ebb and flow of tourism activities, measurable through statistical analyses encompassing visitor numbers, expenditure, transport patterns, employment rates, and admission to attractions. Scholars and policymakers alike have grappled with the challenge of sustaining tourism activities across seasons (Butler, 1998). In addition to the phenomenon’s effects on the economy and society, furthering research on seasonality is crucial as new insights, for example via quantitative studies, could offer optimisation tools (Medina et al., 2022). Cesarani and Nechita (2017) found that seasonality, accessibility, and competitiveness disrupt traditional service models in rural destinations. Despite concerted efforts by tourism stakeholders to design collaborative strategies, spreading events across the year to attract visitors during low seasons, seasonality remains a formidable challenge for emerging tourism destinations in particular (Butler et al., 2001). Central concerns revolve around the substantial alterations in the lifestyles of residents, ensuring consistent access to amenities and preserving overall well-being (Dodds & Butler, 2019; Gil-Alana & Huijbens, 2018). Levin (1999, p. 2003) characterises tourism as a complex, non-linear, and adaptable system where the internal and external environments and factors defy predictability. In insular destinations, extreme climates and remoteness present formidable natural factors that exacerbate the challenges of adaptation (Baum & Lundtorp, 2001; Senbeto & Hon, 2019). Santana et al. (2022) established the need to focus on emerging coastal destinations and evaluate adverse effects by stipulating innovative solutions for connectivity. The importance of favourable connections to the outside world is underscored by Ólafsdóttir and Dowling (2013) and Koo and Papatheodorou (2017) who advocate for infrastructure development in order to stimulate interest in tourism and foster economic development. Numerous studies highlight the significance of air transport and confirmed that airports positively influence connectivity, local retention, social inclusion, and economic prosperity (Alamineh et al., 2023; Florida et al., 2014; Kanwal et al., 2020; Ke & Baker, 2022; Nguyen, 2021; Smyth et al., 2012) leading the local population to positively perceive and support airport infrastructure due to such benefits (Caballero Galeote & García Mestanza, 2020; Halpern & Bråthen, 2011; Song & Suh, 2022). Bianchi and Stephenson (2013) in comparison with Higgins-Desbiolles and Bigby (2022) remark the democratisation of tourism mobility and stress the rights of local residents in such developments. Additionally, Zhang and Xie’s (2023) study shows that airports promote urban economic growth, compared to cities without such infrastructure. The higher the amount of connections between an airport and its surroundings, the higher the potential benefits for an entire region (Lee et al., 2021), in particular in peripheral, small, or mid-scale areas where the improvement of market accessibility is directly dependent on the expansion of outputs, exports, and investment scales (Chen et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2021; Mazrekaj, 2020).

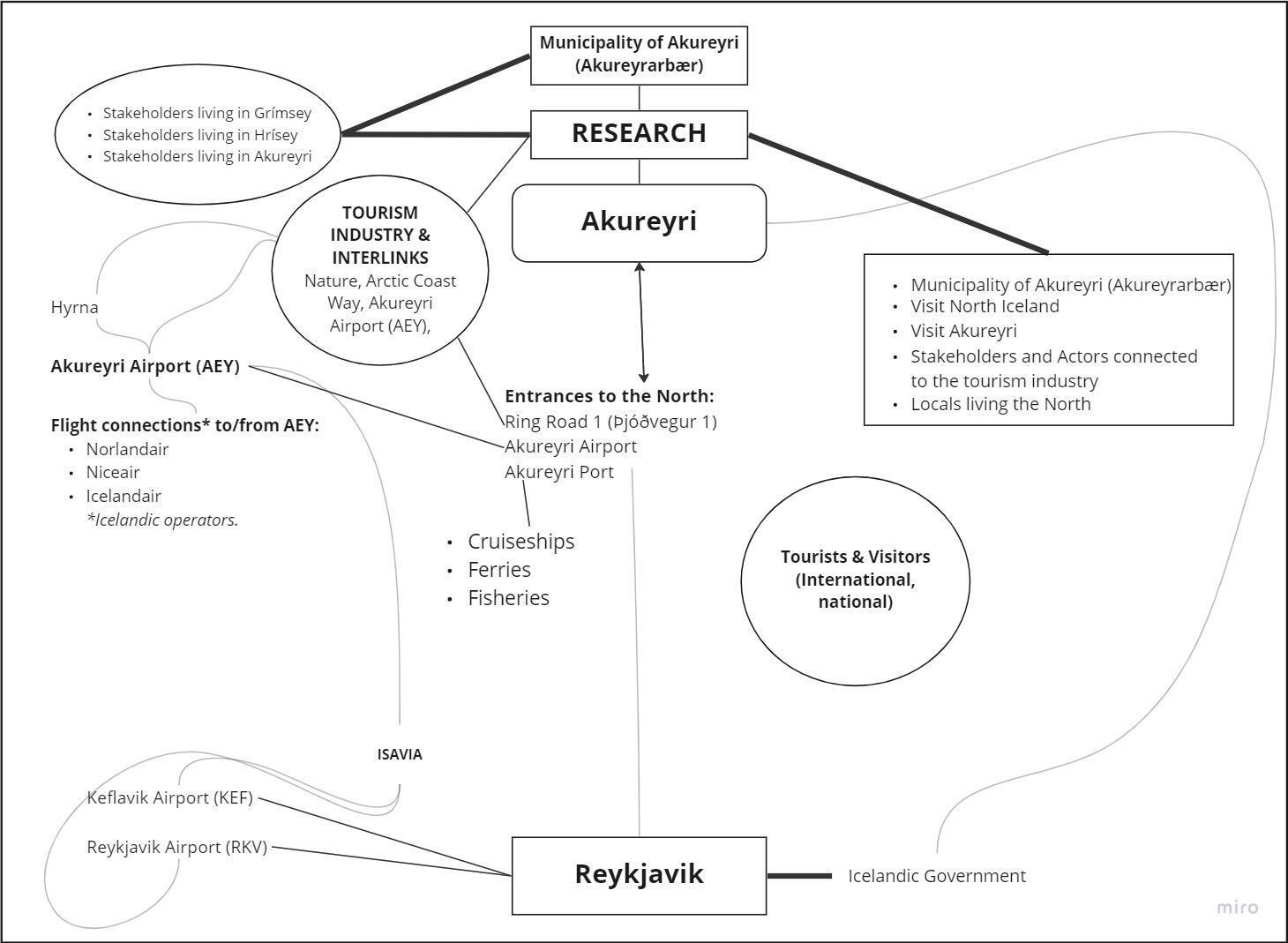

Methodology, Method, and Social Arenas Mapping

This study adopts the social constructivist research paradigm, aiming to construct realities shaped by multiple paradigms. Tourism stakeholders and actors participating in the study contribute to socially constructed knowledge (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). The research follows an inductive approach, inspired by grounded theory guidelines outlined by Peters (2010). Utilising mixed qualitative methodologies, the researchers conducted a total of fifteen qualitative interviews informed by systematic literature review principles (Jahan et al., 2016). Integrating these methods enhances reliability and trustworthiness through triangulation achieved in a thematic analysis (Richards & Richards, 1991) and a comparative analysis across methodologies (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The research commenced with an extensive review of literature followed by a destination analysis that formed the foundation for developing a detailed Social Arenas Map inspired by Clarke (2011). This process involved identifying and mapping the contextual landscape encompassing North Iceland’s tourism industry, its stakeholders, and the country’s overall tourism development related settings during the research period. This multifaceted approach aimed to delineate the non-human elements, companies, and individuals directly or indirectly involved in tourism development. Moreover, it facilitated an exploration of power relations, influence, and contributions to the emerging destination’s progress, which emerged during stakeholder interviews, allowing for new thematic elements to surface. To illustrate the stakeholder landscape, the researchers conducted both a destination analysis and carried out a stakeholder mapping (Nicolaides, 2015). While initial assumptions are inherent in the onset of any research project (Hesse-Biber, 2017), it is imperative to regard the Social Arenas Map as the authors’ representation of observed reality contextualised within the respondents’ environment (A. Clarke & Robertson, 2001). The chosen inductive approach has enabled the manuscript to evolve subjectively throughout the research process (Bryman, 2008).

Interviewing Process

The interviewing process took place over two periods, encompassing a total of fifteen participant-tailored interviews. The first period occurred from February to April 2022, followed by a second round in July and August the same year (see overview in Table 1). During the initial phase, interviews were conducted with residents residing in Akureyrarbær (Municipality of Akureyri). They participated under the condition of anonymity regarding their names and specific employment occupations as requested under ethical guidelines. Each interviewee was apprised of the research scope and purpose and provided consent for recording (American Anthropological Association, 1998). These participants represented communities from Akureyri, Grímsey, and Hrísey, contributing diverse perspectives shaped by the varying nuances of tourism development across the area. The first round of interviews took place at specific locations in North Iceland, whereas the subsequent round utilised web conference software for convenience. The choice of interview locations during the initial round aimed to contextualise and justify methodological interviewing decisions based on the respective work areas of the participants. The second round involved interviews with stakeholders deeply entrenched in regional tourism directly or indirectly linked to the expansion of AEY. These stakeholders offered nuanced insights into North Iceland’s regional tourism development, providing critical perspectives stemming from their extensive knowledge and occupations within the field.

A final composition of both stakeholders and local tourism actors led the researchers to a concise representation of perspectives from a wide range of professionals and residents on proceeding infrastructural and tourism development-related processes. All interviews were recorded and transcribed, and the data sets underwent a thematic analysis, which allowed for a coding process through a simplified data reduction strategy (Saldaña, 2015).

The analysis of primary data collections obtained through desktop research unveiled the disparities among Iceland’s north and south, the intricate dynamics of infrastructure development and the complexity of emerging destinations to position themselves in the global tourism agenda. The Icelandic government has invested six hundred million ISK in augmenting the infrastructural capacity of Akureyri and Egilsstaðir airports to carry the expected tourism flows (Ćirić, 2020). The project can be conceived as a bottom-up initiative which was then supported by national authorities and turned into a top-down strategy. The construction reaffirms the centrality of infrastructure for destination development (Dalimunthe et al., 2020). As a matter of fact, our data uncover a critical factor intrinsically linked to both infrastructure development and regional tourism: the pivotal role of air transport as a security imperative. Iceland, characterised by its dynamic geological features and frequent volcanic eruptions, possesses a distinctive landscape that shapes communities and ecosystems as well as posing challenges (Ágústsdóttir, 2015; Ólafsdóttir & Dowling, 2013). Stakeholders underline the significance of secure air transport in the face of potential disruptions while highlighting the vulnerability of KEF’s location and emphasising the need for alternative sites like AEY for emergency landings:

Now [August 2022] we have these volcanic eruptions. What happens if something disturbs KEF? The importance of seeing that Akureyri [AEY] can be a place where you have the security of being able to get planes down and having space for them, which is a problem today because we can have three planes at the same time, while with the expansion, the situation would improve a lot to handle eventual emergencies and special cases. (Hjördís)

To this complexity and the advanced handling of emergencies in exceptional situations, María Helena adds:

This is a matter of security for international flights and for Icelandic flights, as this is a reserve airport. Last summer there were seven private jets at the airport, which means that not one flight can be diverted to AEY because there is no space on the apron. What if KEF closes and there are ten jets coming and they need to land because of fuel shortage.

Both interviewees identify Iceland’s flight network vulnerability, pinning significant reliance on KEF for international flights while underlining AEY’s potential in emergency situations. Despite the recognition of air infrastructure’s importance, María Helena underscores that several factors impede efforts to bolster air transport and expand airport capacities: “Remote locations like Akureyri struggle with fuel costs and complex landing procedures due to its deep valley location, necessitating specialised pilot training and higher operational costs.” The interviewee’s insights highlight the multifaceted challenges of improving air infrastructures, acknowledging the complexities beyond mere expansion desires, such as geographical constraints and financial burdens, which affect the region’s competitiveness and operational viability in attracting more tourists on a year-round basis (Baum & Lundtorp, 2001; Bjarnason, 2021). Hjaltí from Visit North Iceland stresses the challenge of explaining ‘the job to the state,’ which nevertheless appears to have borne fruit: “We have long been pushing for a bigger terminal and a larger apron. The state has a plan and has declared that it wants to distribute the tourists - that it is better to have more airports and entry points” (Hjaltí).

Hjaltí believes that addressing Akureyri’s development deeply hinges on the regional DMOs’ as well, calling attention to its role in attracting increased investment from stakeholders, who in turn build accommodation infrastructure and facilitate space for conferences and trade shows. Despite the north’s perceived lower attractiveness compared to the south and the capital region, the assertions made by Baggio and Sainaghi (2011) underscore the policymakers’ critical role in mitigating seasonality by leveraging the destination’s existing capacity and economic potential. Guðrún, director of the Icelandic Tourism Research Centre, emphasises that addressing these issues is not solely a responsibility of policymakers as collaboration among stakeholders should form the cornerstone of any strategic management approach:

It is very important that municipalities and communities try to visualise and try to understand how tourism can benefit their livelihood and strengthen them in a positive way in the long run. So, it will not be just to run after tourism, but it is important that they begin to understand how to manage this from the very beginning. (Guðrún)

On a related note, Hjördís notes the government’s disproportionate focus on development in the Capital Area, identified as the epicentre of Icelandic tourism, perpetuating a “core-periphery dualism” (Koo & Papatheodorou, 2017, p. 238) that results in an uneven economic investment. A bias is evident as the overwhelming majority of air arrivals have passed through KEF and gravitated towards stays in the south and the capital region (Icelandic Tourist Board, 2023). The lack of air infrastructure investment in the north relates to a ‘which came first: the chicken or the egg’ problem, as entrepreneurs and policymakers do not want to build anything before, they see the development happening (Smyth et al., 2012). Hjaltí explains the paradigm for the northern region:

We need to start with the nest. And the nest is the airport. Without the nest, we haven’t got any chicken or any eggs… for us in the north, this is the case, this is the reason why it is so vital for us to get international traffic and proper airport facilities. From there, we can build in many different ways, but we need the connection. (Hjaltí)

The sentiments shared by our interviewees spotlight a perceived surge in Iceland’s tourism activity, with burgeoning interest from foreign airlines and travel agencies, signalling an acceleration in the growth pace. Hjördís anticipates North Iceland is emerging as a secondary destination, catering to individuals seeking alternatives to the well-trodden paths of the south: “Many people have already been to the south. Now, people are eager to get to another place, so this is very important for Iceland as a whole, that we have something.” María Helena from Visit Akureyri affirms this feeling, stressing the necessity for winter-time utilisation of facilities to ensure year-round viability:

As soon as we get planes and companies flying directly to Akureyri, people stay longer in the area… They [the entrepreneurs] want to see that they can sell the destination during wintertime as well. It is not enough just to sell during the high season, the peak of summer. Nobody has seen a value for something which is going to stand empty for most of the year, but if you have direct flights coming as well during wintertime… it means that you can hopefully fill up many of those beds also and get a better value out of your investment.

Tourism can play an important role in economic growth while contributing to the development of related services and infrastructure (Nguyen, 2021). Overall, the industry representatives agreed that accommodations, various modes of transport and other services should be in place to tackle the incoming flows, aligning with findings on factors that affect a positive tourism development. These sentiments indicate a strong sense of destination capacity for upcoming developments related to tourism in their area and North Iceland.

Extended Capacity Development

Amidst the potential economic benefits, the rapid pace of emerging destinations can catch stakeholders unprepared for substantial tourist influxes, necessitating the enhancement of local community knowledge and human capacity (Getz & Nilsson, 2004; Novelli & Burns, 2010). Hjördís highlights the undersupply of facilities in the area for an all-year destination:

I think that we don’t have enough hotels, we see that in the summer… This doesn’t happen overnight but in an ideal world this is what we need. Then of course infrastructure. There will be demand for more accommodations and more activities and services. A reason for tourists to stick around in that particular area… we need more of this and all year-round in the less developed areas, not just in Akureyri. (Hjördís)

If the latter statement further accentuates the need for innovative services and products as compelling assets for diversifying the existing offer compared to competitive tourism destinations (Pham et al., 2018), another contributor stresses the importance of understanding multiple aspects, including tourists’ needs and wants in the current economy (Pike et al., 2016):

The pandemic makes it obvious that not all segments are the same… foreign tourists were not arriving, domestic tourists started to visit, their requests were different, for example whale watching was not so demanded. Now, service providers are still wondering about what kind of activities tourists would like to experience if they are in town. (Anonymous)

Both respondents foresee an uncertain scenario and at the same time underline the unique value of connectivity. Academics highlight the need for more regional-based island research to compensate for the lack of knowledge and experiences (Qu et al., 2023) and distinguish destinations as conglomerates of goods and services which provide unified visitor experiences (Benur & Bramwell, 2015; Buhalis, 2000). Despite the imminent development that the region is expected to undergo, interviews with stakeholders revealed a spectrum of views regarding the area’s future trajectory. Data gleaned from our fifteen interviewees align with similar studies from Norway, Spain, and South Korea where stakeholders’ opinions and relations to airport developments were examined (Caballero Galeote & García Mestanza, 2020; Halpern & Bråthen, 2011; Song & Suh, 2022). In this particular research, the respondents see the benefits of the airport expansion project and consider tourism development as an opportunity for democratisation through the airport expansion, which could allow emerging insular destinations to be connected with the outside world (Higgins-Desbiolles & Bigby, 2022). Eyrún emphasises the locals’ notions about airport expansion in relation to the ongoing development:

Locals understand that the development is not only for tourists. Previous studies carried out by the Icelandic Tourism Research Centre have shown that majorities of residents in the north overall seem satisfied about tourists in their areas, and further see how enterprises benefit their daily lives, for example, through increased connectivity to the outside world. (Eyrún)

Her observation is that locals grasp that the development is not solely for tourists (emphasis added), while noting the local community’s genuine satisfaction with these advancements, as stated by Lee et al. (2021), who emphasise that inclusive approaches have the ability to foster sustainable growth and be beneficial for the local communities in the region. Eyrún’s point of view is shared by other respondents. One states that “the vast majority of people I speak to are happy to directly fly to Denmark, London and maybe Germany next year [in 2023].” (Hjaltí), while another adds:

Everybody living here in the north, and probably also in the east and west, they really like that this airport is expanding and that we will get more flights. They see opportunities both for tourists to come to them, and then also themselves being able to go abroad more easily. (Hjördís)

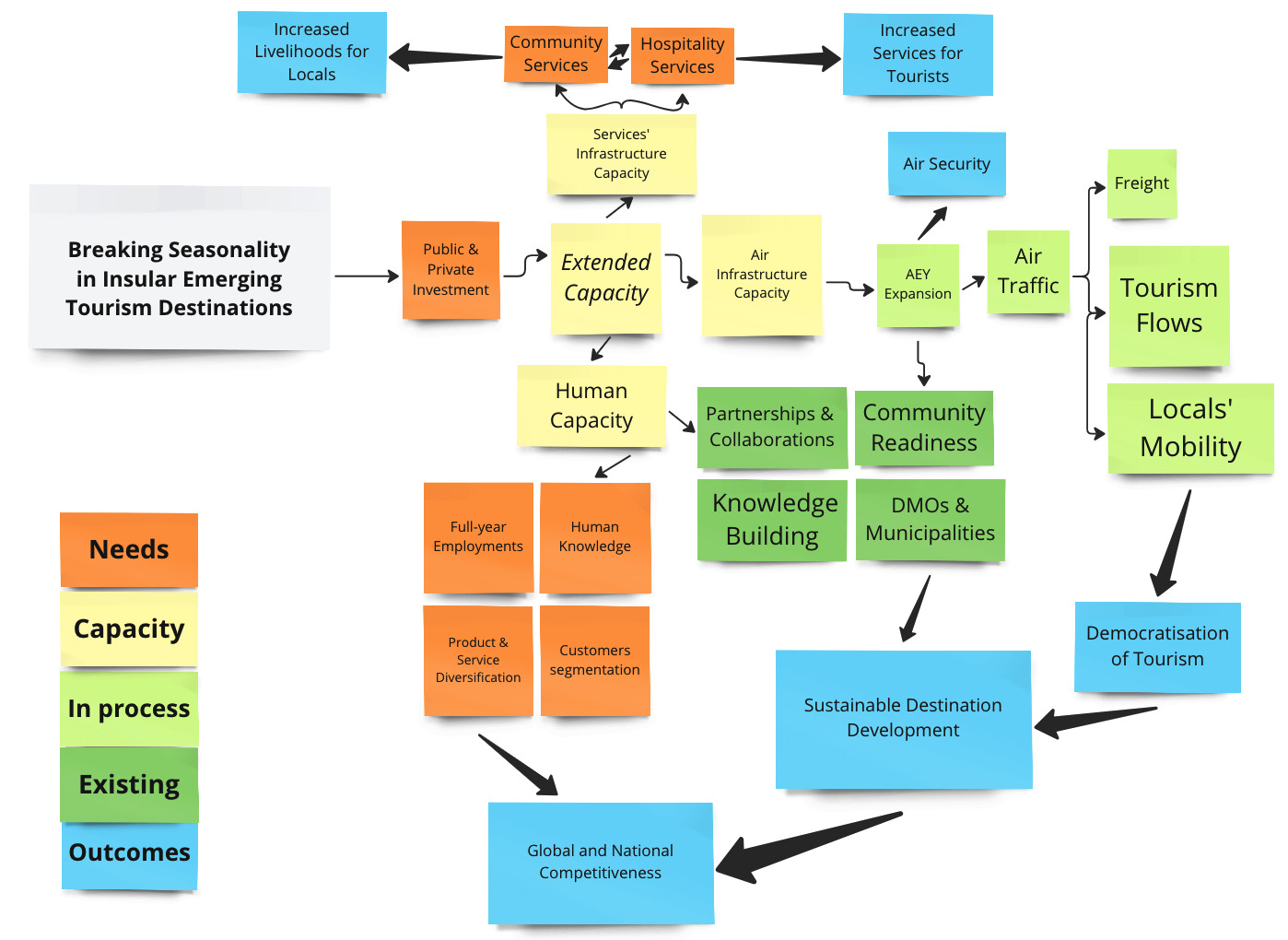

Respondents are indeed on a par with literature findings and initiatives by the Icelandic Route Development Fund which show support for expansion (Government of Iceland, 2015), indicating that strengthening air infrastructure could have the potential to enhance the wellbeing of residents (Florida et al., 2014; Ke & Baker, 2022) and extend their lifeline in the region as a conglomerate of communities constituting an emerging insular tourism destination (Rodríguez & Raúl, 2018). Our data shows that capacity building strategies need to be developed simultaneously at a destination level in a more holistic approach. In this study we identified and analysed the groups of infrastructure capacity, human capacity, services’ infrastructure capacity as an amalgam under a shared term ‘extended capacity.’

Discussion

The study delves into the pivotal role of air infrastructure as a catalyst for hospitality development in emerging insular destinations. Figure 2 shows that in the case of Akureyri, adjusting seasonality is not a linear process beginning from the mere investment on air infrastructure, but from the point of designing policies to simultaneously develop the aforementioned ‘extended capacity.’

While the airport expansion and its investment are viewed by the interviewees as an asset towards socioeconomic improvement and a tool to tackle existing seasonality issues, it proves to be complex in practice. Seasonality has been examined by various academics (Butler, 1998; Butler et al., 2001; Getz & Nilsson, 2004; Gil-Alana & Huijbens, 2018; Pham et al., 2018; Sæþórsdóttir et al., 2019; Senbeto & Hon, 2019; Þórhallsdóttir & Ólafsson, 2015) and studies from various locations have illustrated the complexity of overcoming and tackling the phenomenon. In this study, and as visualised in Figure 2, the authors have identified other ‘extended capacity’ components that are vital to consider while designing processes for better handling seasonality challenges.

Baggio and Sainaghi (2011), along with and Novelli and Burns (2010), concur that comprehending the pivotal influence of policymakers in adapting to seasonality by maximising available capacity and economic opportunities reveals a distinct, yet somewhat uncommon level of stakeholder preparedness. This readiness manifests through an acute awareness of sustainable development facets, fostering a shared responsibility for destination development alongside policymakers.

Baum & Lundtorp (2001) argue that the geographical constraints and financial burdens faced by emerging insular destinations significantly impact their competitiveness and year-round operational viability. The willingness displayed by interviewed participants to address seasonality issues and collaborate to enhance the destination’s success by attracting more tourists represents a paradox. Despite their readiness, the destination lacks sufficient hotel capacity and services, raising the question: What should be prioritised, attracting investment or tourists? Our primary data confirm a deficiency in hospitality facilities, a significant impediment affecting residents’ livelihoods due to the absence of a competitive array of on-site tourism services and products.

Policymakers and stakeholders should be aware that the insufficiency of resources and capacity may perpetuate a persistent core-periphery divide (Koo & Papatheodorou, 2017), leading to a scarcity of high-calibre locales (Howie, 2003; Ritchie & Crouch, 2003; Wyckoff, 2014). This challenge is mirrored for destination planners who face the risk of increased fluidity in the movement of goods, people, and ideas, potentially compromising the pursuit of sustainable development (Santana et al., 2022) and favouring a privileged subset of stakeholders (Jovicic, 2016). Indeed, the case of Akureyri underscores the pressing need to fortify local community knowledge and human capacity, a critical factor emphasised by Pike et al. (2016) as essential for community readiness. Hence, we argue that an ‘extended capacity’ management approach represents a pivotal, yet frequently overlooked aspect in mitigating seasonality in emerging insular destinations.

Academics argue that the advantages for host communities to join the tourism enterprise are numerous, ranging from enhanced access to amenities and facilities to the democratisation of tourism enabled by robust mobility and connectivity to the outside world (Caballero Galeote & García Mestanza, 2020). As seen in the figure 2, the expansion of AEY runways not only spurs destination growth but also promises benefits for residents in both eastern and western regions, fostering equitable mobility for all Icelanders and encouraging a more evenly distributed tourist flow across the country. This expansion signifies improved regional air safety. The significant investment totalling six hundred million ISK to develop the extension of AEY airport holds a dual-folded agenda: the revitalisation of the north and a transformative impact on the global tourism landscape (Centre for Aviation, 2022; Ćirić, 2020).

Conclusion

The analysis of air infrastructure’s role as a catalyst for hospitality development in emerging insular destinations reveals several critical seasonality aspects and potential future directions. The study emphasises uncertainties surrounding forthcoming advancements following the airport expansion, including necessary services and products required, together with the unspecified tourism flows and investor interest. Advanced transport connectivity significantly impacts various aspects of a place, yet despite Iceland’s poised tourism growth, the diminished inflows during shoulder seasons present a fundamental challenge for the northern region’s prospects for sustainable development. Stakeholders apparently prioritise the fast development track even though they are aware about some aspects of sustainability, however, the absence of year-round businesses poses risks for investors and affects the region’s tourism potential. Furthermore, it was identified that ‘extended capacity’ in destination hospitality infrastructure is essential to address the needs of both locals and visitors. Additionally, we advocate for simultaneously building extended human skill capacity to diversify tourism offerings by stakeholders as crucial to transform the future of insular emerging destinations. Addressing seasonality and strengthening the ‘extended capacity’ framework simultaneously with infrastructure capacities are critical to extending benefits to the Northern Region’s residents and visitors. Air transport enhancements can influence Akureyri and the broader northern region, fostering off-peak travel, air security in the region, service diversification, and spreading investment. We remark that collaboration among tourism stakeholders is crucial, therefore the methodology employed highlighted and unveiled inclusive community engagement, socioeconomic benefits, and challenges inherent in remote insular destinations, further showcasing the need for comprehensive analysis in future research endeavours. The paper provides a Social Arenas Map where interdependencies among stakeholders and actors in North Iceland are identified, showcasing the broad connectedness together with the links between local and national tourism ecosystems. As aviation connectivity unfolds, it offers an opportunity for North Icelandic stakeholders to collectively strategise sustainable development, potentially fostering responsible travel experiences by mobilising tourism flows all over the country and not solely consolidated destinations, and thus, increase the visits to more insular emerging destinations.

Concluding Remarks

Our contribution to the Island Studies Journal showcase a span of complexities related to seasonality and air infrastructure development in a remote insular destination. Other capacity types focusing on environmental aspects, such as CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions, have not been studied. Similarly has the cruise tourism industry and its influence on carrying capacity and local residents’ sentiments hereto been left out of the scope of this research. Hence, for a greater overview, valuable to both practitioners and academics, the authors propose a continued research focus on environmental aspects and an in-depth analysis of residents’ opinions to the presence of tourists. The mere fact that interviewed stakeholders and locals do not oppose sustainable development could suggest a solid basis for a democratised tourism development (Higgins-Desbiolles & Bigby, 2022). A progress counting both locals and tourists could further a prosperous development alongside the expansion of AEY and in tackling seasonality issues. Ultimately, it calls on policymakers’ support to furthering development (Butler, 1998) and adjusting seasonality conflicts and imbalances in the northern region of Iceland. The actualising of implementations carried out in practice could ultimately determine the state of tourism development in Akureyri and neighbouring areas, and potentially have an effect on Iceland’s sustainable tourism progress.