1. Politics and remoteness: Decisions made by others

The complexity of islands is often overlooked, either due to perceptions that they are simply an extension of the mainland or because multiple islands tend to be grouped together for analysis. As such, opportunities to identify the specific characteristics of these territories are missed, thus exacerbating inequalities in terms of potential, access and expectations (Baldacchino, 2008; Hay, 2013; Lois, 2013).

There is a debate concerning the top-down approach of state intervention initiatives that identify problems – conceptualised as shortcomings or deficiencies – and propose solutions that pay little attention to the reality of everyday island life. For example, place-centred policies, which do not consider the people living there, look at problems in a fragmented way with the expectation that addressing one part will significantly contribute to solving the entire problem (Quintana Vigiola, 2022). Then there are the welfare-based approaches, which highlight the vulnerability and dependence of island inhabitants as reasons to attend to them quickly and efficiently (Fernandes & Pinho, 2017; Román, 2020), even if this means overriding local expectations or making them dependent on the political centres through subsidies (Olfert et al., 2014). Tensions arise when measures are introduced that are not agreed upon locally, do not correspond to local interests and may even interfere with them, promoting a sense of disappointment and frustration among islanders (Bustos & Román, 2019; Lois, 2013; Mascareño et al., 2018).

Inhabiting islands is subject to external decisions, given the historical centre-periphery relationships often established with the continent (Favole & Giordana, 2018; Lois, 2013; Mascareño et al., 2018), which can result in their distinctive features being overlooked. This marks a growing disconnect between inhabitants and decision-makers, especially those in public roles, where territorial identity contrasts with political identification or a sense of belonging to a state project. Thus, a sense of unfairness is amplified by tensions in terms of complex and poorly formalised decision-making processes (Baldacchino, 2020; Korson et al., 2020) or of conflicts resolved from a central and distant authority (Bustos & Román, 2019; Delamaza Escobar et al., 2023; Núñez et al., 2019).

Key differences regarding identity emerge in relation to other places: inhabiting an island carries with it a biographical hallmark derived from the daily experience of living with a liquid and permeable border. While there is an ongoing debate concerning the correctness of limiting the notion of islands to land surrounded by sea – in which relationships and areas of influence could become more meaningful in terms of islandness (Pugh, 2016; Rankin, 2016) – a phenomenological perspective allows us to attribute a role to the ocean itself, in the sense that it must be adjusted and adapted to, and somehow welcomed as a participant in the day-to-day (Álvarez et al., 2019; Hay, 2013; Hayward, 2012). This, in turn, defines a notion of closeness with other people who inhabit other islands (Ducros, 2018; Randall et al., 2014).

In this work, we aim to understand perceptions of the role of the state and how its interventions are assessed from a remote and sparsely populated island. We focus on the centre-periphery relationship in a sub-national context, where decision-making and control of state interventions is top-down, reproducing asymmetries and exclusions in a fractal and multi-centred model (Favole & Giordana, 2018). Also, visions of islands as lagging behind, located beyond the continental peripheries, are consolidated (Knoll, 2021). All of this calls for adaptive measures to guide the role of the state according to local capacities and needs (Amoamo, 2013; Chia & Torre, 2020). Our research question is about what is involved in inhabiting an island when assessing the presence of the state in these places. The contribution of this paper is an analytical proposal of islandness in a sub-national context, recognising different elements that together shape an insular political position. To do this, we examine how politics and territorial integration take place in remote areas. We present the focus on islandness as deployed in processes of identity, politics and territory and we describe our study case: the archipelago district of Guaitecas in southern Chile.

In Chile, territorial management is vertical, with the same institutions and policies in place for the length of the territory – a system with little practical value in such a geographically and socially diverse country. Administrative structures are replicated in very diverse territories, both in terms of their distance from the centres of decision-making and their geographical characteristics (Aroca & Soza-Amigo, 2013; Boisier, 2004; Galilea Ocón & Letelier Saavedra, 2013), as well as the expectations of inhabitants (Núñez et al., 2019; Román, 2020). Until 2021, the only decentralised territorial administration was provided by municipal councils, which had significantly reduced resources and power available to them compared to the sectoral agencies at the centre. Since then, the so-called “regional authorities” have been elected, but these still have limited power.

The Aysén region, to which Guaitecas belongs, has the lowest population nationwide – a fact that impacts the possibilities of representation for its inhabitants. In this case, the image of democracy as the electoral representation of each and every individual tends to obscure territorial diversity. The size of the population in this part of the country and the high concentration of inhabitants in the Chilean capital mean that it does not have the leverage to place debates that take specific local issues into account on the national agenda (Bronfman, 2013; Gamboa & Toro, 2022), accentuating the hyper-peripheral nature of the relationship between the island and the mainland (Favole & Giordana, 2018).

Inhabiting islands requires a capacity for innovation and creativity in adapting the available means – whether material or institutional – to the needs of territories for which they have not been designed. But it also requires creativity to overcome the challenges and barriers imposed by the centre-periphery relationship with the mainland (Amoamo, 2013). We find new forms of territorial management and governance, which also highlight the discrepancies between available resources, imposed goals and local aspirations, emphasising the risk of implementing iconic yet irrelevant or inefficient initiatives and wasting opportunities to strengthen governance in these territories (Nurhasanah et al., 2023).

2. Islandness as a political position

Through the notion of islandness we refer to three interrelated arguments: those of politics, territory, and identity. Inhabiting an island is a particular experience that involves very clear boundaries and experiences related directly to the geographical context (Hay, 2006; Vannini, 2011). Island biographies are marked by the impossibility of accessing or leaving an island in the event of poor weather; the distance involved, which necessitates prior planning of all journeys; or the lack of services that, in territories with better connections or closer to large, populated areas, are guaranteed. The sea and the coast represent a frontier between the familiar and the unfamiliar, between safety and uncertainty (Hay, 2013; Hayward, 2012; Pugh, 2016; Rankin, 2016); as a barrier, it is permeable rather than insurmountable.

These biographies construct stories that speak to inhabitants of islands everywhere, creating an insular perspective that contrasts with that of the mainland, which knows little of such experiences (Bustos & Román, 2019; Ducros, 2018; Vannini, 2011). As such, islandness is linked to everyday life in conditions that differ from those of other territories, whether for geographical, historical or political reasons. From here, a dichotomic notion of island identity is constructed, characterised by an opposition to continental principles and values (Grydehøj, 2016), which is at the same time liminal, given the permeable and mobile character of the sea as a border (Wang & Bennett, 2020).

The political element derives from previous relations with the institutional structure of the mainland. The literature describing the links between island inhabitants and state structures highlights emotions such as frustration and anger (Lois, 2013; Mascareño et al., 2018; Parker, 2021). These links have taken dramatic forms in Chile with the occupation of the Rapa Nui and Tierra del Fuego Islands where state sovereignty served to facilitate and legitimise economies that depend largely on the abuse – ranging from slavery to genocide – of local inhabitants, as recently as the twentieth century (Corvalán, 2019; Foerster, 2012; Foerster et al., 2014; Harambour & Barrena Ruiz, 2019). These negative perceptions remain in effect today in response to centralised decisions that remain largely irrelevant, as they stem from mainland agendas and impose a greater burden at the local level, without local demands being considered (Román, 2020, 2021).

The territorial arises from participation in public debate to foster inclinations regarding disputed agendas that benefit local interests. This is motivated by the perception that decisions taken at the central level harm the inhabitants of distant territories (Álvarez et al., 2019; Barton & Román, 2016; Cramer, 2016). In this sense, islandness is the manifestation of a process that channels frustrations, identities, and interests to dispute the power of the mainland (Bustos & Román, 2019; Mascareño et al., 2018).

Understanding these three arguments of identity, politics, and territory simultaneously through the notion of islandness avoids the emergence of causalities and prioritises their interrelation, especially in terms of political positioning. Island identity also feeds on a perception of exclusion that reinforces the sense of belonging to a community and of distinction from mainland actors (Barton & Román, 2016; Randall, 2021; Randall et al., 2014; Vannini, 2011) with self-esteem as an island inhabitant presenting itself in dispute against mainland expectations. As such, islandness can also be understood as a way of defining one’s place in the world within contexts of social destructuring (Giddens, 1996). Frustration can also be seen as somewhat of a given insofar as a strong distinction between island and mainland will give way to less tolerance of actions undertaken from mainland administrative centres (Bustos & Román, 2019; Ducros, 2018; Mascareño et al., 2018) or to consideration of its population without explicit acknowledgement of the territorial context (Korson et al., 2020). Finally, the struggle for spaces of power can be characterised from the mainland perspective as the advance of populism, especially if there is no understanding of the reasons behind islanders’ demands (Lois, 2013; Parker, 2021). However, it can also fragment political positioning at the local level, as in the case of leadership originating from other islands or, more notably, from the mainland.

Lastly, it is worth raising the question of a possible geographical determinism inherent to insularity. The island condition imposes a limited material foundation upon which relations of dependence on the mainland are inevitably built (Hayward, 2012; Pugh, 2016). For example, waste management often requires the transfer of refuse to designated locations off the island, while the majority of processed products come from the mainland (Bergamini et al., 2021; Kelman & Randall, 2018). Certain services are also only available off the island, where choice is greater, quality is higher, and prices more attractive. However, these relationships of dependence can also be found inland, meaning that the obligation to resolve everyday problems outside a given geographical area is not exclusive to island areas (Cramer, 2016; Howard et al., 2016; Tuan, 2007). Two further mutually reinforcing factors are derived from island status: the social construction of a territorial identity and the trajectory of unsatisfactory relations with mainland powers. Thus, the natural barriers of the sea and the coast are part of a larger issue of which the condescension with which mainland powers govern island areas is also a part. Behind islandness lies a fundamentally political and historical phenomenon that feeds on the geographical situation in which it manifests itself.

3. The arrival of the state in Aysén

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Aysén region was the only part of the Chilean territory that had not been formally incorporated through a political-administrative process. This fact is fundamental to the imaginary of abandonment and oversight in the region (Grenier, 2006; Rodríguez Torrent, 2021). Another factor is sovereignty exercised mainly by private entities (livestock concessions, entrepreneurs, settlers, and seasonal inhabitants) both on the mainland and on coastlines and islands, all of which contribute to a sense of state absence (Harambour, 2019; Marín, 2014; Núñez et al., 2010). The delay in integration was due both to challenges of connectivity and to notions of Aysén as an unoccupied territory (Harambour, 2019; Ibáñez Santa María, 1972) with no pre-existing inhabitants and reserved for environmental conservation, thus neglecting any sense of legacy in the use of the place (Núñez et al., 2014).

The state only began to appear in the region in the early 1900s with the foundation of the first settlements in mainland Aysén. The coast remained untouched. The first state authorities for Aysén were elected in 1948, and it was not until the following year that the region’s inhabitants were able to vote in parliamentary elections. The first elected parliamentarians had no direct connection to the territory, originally representing constituencies in the present-day province of Llanquihue in the Los Lagos region to the north. They were men from a variety of cities and localities in central and southern Chile, such as Santiago, Valdivia, and the island of Chiloé.

The 1969 elections saw voting on the first deputies expressly responsible for Aysén. The people of Aysén chose a teacher born in Coyhaique (Baldemar Carrasco, Christian Democratic Party) and a doctor (Leopoldo Ortega, Communist Party) – both with a history in the region and political leanings to the centre and left, respectively (Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile, 2020). Senators continued to be elected in conjunction with the island of Chiloé and the Magallanes region to the south.

It was only in 1989 that the Aysén region was able to vote for its own senators: Hernán Vodanovic (Party for Democracy) and Hugo Ortíz (National Renewal) – both lawyers and members of the Santiago elite. The deputies elected during this period were mostly men with experience in the Aysén region and from a range of professional backgrounds (engineers, veterinarians, lawyers), with centrist parties dominating. Since the 2000s, the majority of elected deputies have had a background in Aysén, and there have been no apparent links with business groups. For the first time in the history of Aysén, the legislative period of 2017 saw the election of senators with political and professional backgrounds and links to the territory: David Sandoval (Independent Democratic Union) and Ximena Órdenes (Party for Democracy). This was also the first time that a woman had been elected as a parliamentary representative of the region (Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile, 2020).

Democratic parliamentary elections came later to Aysén than to other regions of the country, a factor that adds to the centralism involved in the definition of its representatives (cf. Rosales, 2009). Electoral processes for the region’s deputies and senators only began in the mid- and late-twentieth century, respectively. To this are added the difficulties faced by inhabitants in accessing their polling stations due to the serious connectivity problems from which the region has suffered historically, especially for the inhabitants of rural and isolated locations.

4. Methodology

Our case study is located in the archipelago district of Guaitecas in southern Chile. It allows us to generalise our findings to other contexts (Yin, 2012) in which distance or islandness may cast light on similar processes. In addition, the case study design allows us to simultaneously address ongoing phenomena and historical data through primary and secondary sources (Yin, 2009).

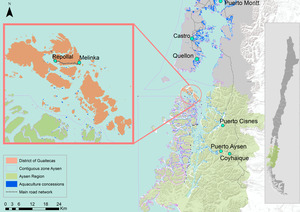

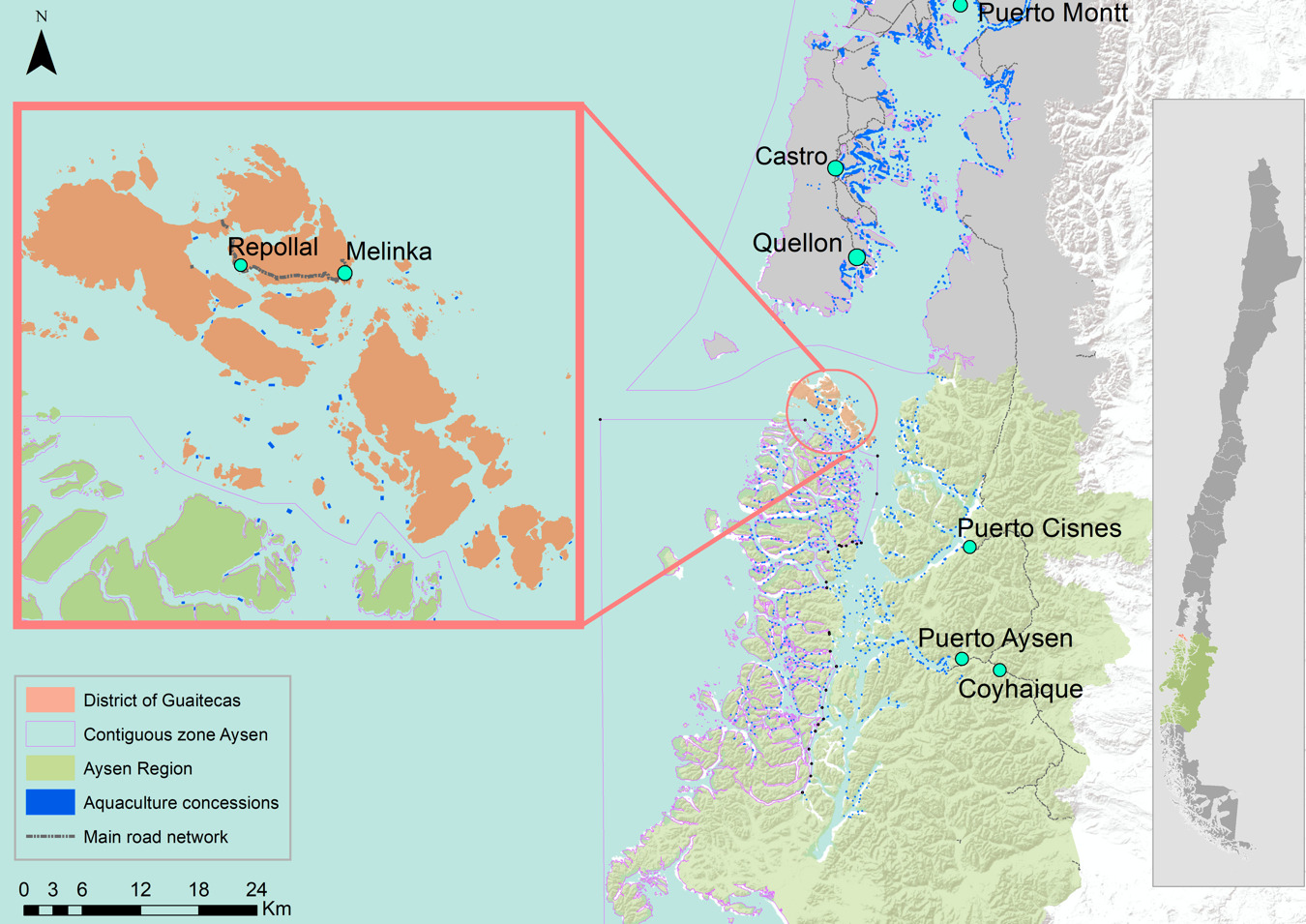

Guaitecas comprises around 40 islands and covers an area of 620.2 km2 (I. Municipalidad de Guaitecas, 2018). Almost all its 1,843 inhabitants live in the villages of Melinka and Repollal on Ascensión island. Guaitecas is part of the Aysén region, but maintains cultural, family, and economic ties with the Los Lagos region (see Figure 1). Its location leaves it in a unique situation. It lies in the far north of Aysén, around 24 hours by land and sea from the regional capital Coyhaique and 6.5 hours from the nearest urban centre with basic services and commerce (hospital, banks, pharmacies, public offices). However, it is only 5 hours by sea to Quellón, in the Los Lagos region – a town of over 27,000 inhabitants.

Guaitecas lies within the main fishing grounds for the red sea urchin (Loxechinus albus). Chile accounts for 43% of global echinoderm catches (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, n.d.). The Aysén region is the largest contributor with 33.3% of the national total (Servicio Nacional de Pesca y Acuicultura, n.d.). The Guaitecas archipelago is in the middle of the so-called contiguous zone: a maritime area in which, unlike the rest of the country, fishers from one region are permitted to operate in another in exchange for compensation paid between their respective regional governments. Paradigmatically, national legislation created on the subject has only been implemented in this particular case, establishing that fishers from the Los Lagos region are also permitted to work in the Aysén region (Álvarez B. et al., 2016), but that the fishers of Aysén cannot operate in other regions.

Furthermore, the district lies in the middle of the salmon farming region. This is a major industry for Chile, which ranks second in global production (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, n.d.), and Aysén is the country’s second most important region for aquaculture. There is also significant naval and air traffic in the region, along with diving, accommodation, and transportation services (Saavedra, 2017; Saavedra Gallo, 2015; Saavedra Gallo et al., 2016).

Its population originates from all over Chile. The majority are fishers and their families attracted by the various booms in maritime productive activities. They maintain ties with their families back home, mainly on the island of Chiloé or in Puerto Montt, capital of the Los Lagos region. The settlement of Guaitecas occurred during a series of productive rushes, beginning with logging (mainly cypress) in the mid-nineteenth century (Martinic, 2005; Molinet et al., 2018; Ponce Figueroa et al., 2009; Saavedra Gallo et al., 2021). The founding of Melinka in the late 1850s marked a milestone in the formal occupation of the archipelago (Saavedra Gallo, 2001; Ther-Ríos et al., 2021), although it would be a couple of decades before settlement became stable (Torrejón et al., 2013; Westhoff, 1867). Today, the district is home to a small but growing population, resident mainly in Melinka itself, and has a significant proportion of people of Huilliche-Lafkenche indigenous heritage. The archipelago’s predominantly productive activities are evident in its overwhelmingly male population. Its economic dynamics show contained levels of income poverty, but the level of multidimensional poverty is higher than that for both the region and the country due to the lack of services (see Table 1).

Secondary sources consulted consist of public reports, historical reports on the study area, population and state investment statistics, and scientific literature, which we subjected to review (Castro Posadas, 2013). These were selected according to criteria of location (they are focused on the study area), historical (they allow us to recognise tracks and patterns of occupation and construction of a state project), and public concern (local press) as shown in Table 2. These sources were subjected to content and thematic analysis to guide the data collection and the selection of theoretical approaches.

The main data source are the accounts of 39 informants gathered through semi-structured interviews between September 2021 and October 2022. This technique provides access to the various terms with which people refer to their reality, avoiding the biases and exclusions that often emerge from rigid questionnaires, and facilitating the capture of respondents’ own forms of expression (Creswell, 2014; Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002).

Selection of informants came through theoretical sampling (Glaser & Strauss, 2017) to represent leaders of organisations present in the district: neighbourhood associations, fishing unions, trade unions, sports clubs, and indigenous organisations. The sample also included district-level elected authorities and state officials with positions of municipal responsibility or involved in the public services present in the district. In addition, we interviewed representatives of private companies operating in Guaitecas.

Interviews were conducted in the district of Guaitecas, except for two conducted in the city of Puerto Montt and one via video call. The interviews lasted approximately one hour and were audio-recorded for subsequent transcription, with the prior authorisation of the participants established by signing an informed consent form in which the anonymity of the data was made explicit. To ensure the confidentiality of the identity of the interviewees, codes were established for each interview and any explicit mention of an organisation or person that could compromise the anonymity of the quotations presented was omitted.

There were four axes in the interview guideline, in addition to an introductory section to characterise the informant and their relation to the region: 1) characterisation of the territory (particularities from inhabiting); 2) local politics (issues of interest, representativeness, and legitimacy and spaces for discussion/deliberation, participation, and expectations); 3) representative democracy and state (appreciation of the state and elected authorities, relationship of these with the territory and its inhabitants, escalation/channelling of demands); and 4) future trends (development options, possible changes, contrast between ideal future, and possible future). Triangulation techniques were applied at various stages of research, addressing informants previously interviewed and those with academic experience on the topics addressed.

Throughout interviews, we have assessed the pertinence of the emerging categories, their relative relevance, and the analytical possibilities of guiding interpretations in other contexts. Table 3 provides a summary of the categories and codes derived from the thematic analysis that we used to organise the data and represent it according to consistent criteria (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and avoidance of linearity, whereby purely temporal organisation can induce chronological causality (García, 2013).

5. Who is the state in Guaitecas?

For the inhabitants of Guaitecas, the state is a distant and foreign entity. It is seen as an external and centralised figure whose body is located in distant cities, such as Santiago, Valparaíso, or Coyhaique (depending on the service in question), and which has the ability to make decisions and act to solve problems. The municipal council is seen as an intermediate entity that stands out from the rest of the public structure, does not necessarily represent a gateway to the state, and has only a limited capacity for problem solving. For inhabitants it is a familiar and easily accessible space, but it also implies that, in the event of political differences with the administration of the day, access to certain spaces can be cut off. At the same time, public institutions present in the territory are not always perceived as being part of the state, since their work is focused on the management and delivery of services and they are limited to directing the demands of the population through regular channels, without any guarantee of satisfactory outcomes:

The municipal council is the state, but, strangely, it’s not seen as such. They’ve gained a degree of independence because they have faces, they’re people, they’re neighbours; so for them the state is [the ministerial authority]. It’s a stranger who comes from elsewhere, who can sort your life out, or maybe not, but it’s very difficult to get it to do so. It’s like… I don’t know, a shooting star. Suddenly you can make a wish and it solves a problem. That’s the state. Far, far away (employee of a private company, April 2022).

The public officials who embody the figure of the state in Guaitecas are professionals from mainland Chile. They are seen as unfamiliar with the dynamics of the district and its inhabitants, and as unreliable and barely credible, making it difficult for them to establish ties with the community. The local inhabitants involved in public service live with the dichotomy of being part of a regulatory or supervisory body and, at the same time, fellow residents. They are in the middle of the tension that characterises the definition of identities in these places, in which continental values become fundamental to assert an insular position (Grydehøj, 2016). Their loyalties are questioned whenever they are faced with discontent over the functioning of a given service or institution. In turn, they express frustration and exhaustion associated with their daily human interactions and the levels of institutional bureaucracy that operate in the archipelago.

For example, newly arriving professionals initially attempt to enforce the rules before realising the need for flexibility and the application of adapted criteria based on local conditions. In some cases, bureaucracy within their own institutions makes it difficult for them to make decisions in accordance with the specific requirements of their work, as they are designed in a sectoral, fragmented way, without considering the complexity of the place itself (Quintana Vigiola, 2022), and they often struggle to remain in the district for long. Such professionals are quickly replaced, and the cycle begins again, thus reinforcing the opinion of inhabitants that those who come from elsewhere neither know nor understand them (cf. Cramer, 2016).

6. What is expected of the state?

Allocation of resources for the effective management and implementation of public policy is challenging in an archipelago district. The inhabitants of Guaitecas expect solutions to the main shortcomings of the district: sewerage and sewage treatment, hospital car, quality drinking wate, landfill, housing, up-to-date land management and planning instruments, and better access to public services. Although the authorities are well aware of these problems, their resolution requires political will and coordination between various agencies. However, this is not happening at the regional level (Montecinos, 2020) and the national agenda transcends local debates (Rosales, 2009). Local expectations therefore point to direct investment in the basic problems that make daily life more difficult, but which also hinder local development, including the possibility of starting a business:

The colour of the water, whether it’s drinkable, whether I can drink it. They also require sanitary certification for some businesses. So, if you want to run a tourist attraction, then you come across the barrier that, for example, we don’t have mains sewerage. There are a lot of requirements and, as people are unable to meet all of them, we simply cannot move forward (artisan, October 2021).

This conundrum provides insights into the assistentialism with which decisions are made in places such as Guaitecas: when developmental initiatives are not observed, this serves to reproduce a perspective that renders the territory responsible for its backwardness (Román, 2020, 2021). Since the allocation of resources and targets is often performed externally, there is a general lack of awareness concerning local expectations and the challenges of inhabiting (Bustos & Román, 2019; Ducros, 2018). Thus, in Guaitecas we find examples such as port infrastructure that is unsuitable for artisanal fishing, urban amenities that are crumbling because of a failure to account for the marine environment in design specifications, or productive projects that have not been adapted to local interests and capacities. This points to the need not only for a more significant injection of resources, but also for greater involvement on the part of local actors in decision-making at both the municipal and regional level, where they can express their needs and expectations.

Combined this leads to a sense of disaffection with politics and state institutions (Cantillana Peña et al., 2017; Mascareño et al., 2018). However, people find spaces for participation and deliberation through the various social organisations that exist at the local level. Those best known among our informants are fishing unions, sports clubs, and neighbourhood associations. In addition, there are indigenous organisations (one community and one association), social organisations, and productive organisations.

Interest in participating in these organisations is linked to obtaining immediate benefits for the satisfaction of specific needs such as the delivery of money or material goods. As such, they tend to swing into action in response to particular circumstances but struggle to maintain enthusiasm for long-term goals. Once the immediate issue is resolved, many of them return to a dormant state of existence.

Those organisations with a stronger presence in public life have one thing in common: charismatic leaderships that succeed in positioning their needs within discussions and challenging and confronting authorities directly. The idea has also spread that protest is the only way of ensuring that external authorities pay due attention to local voices. This has led to frequent blockades of transportation hubs, namely the port and the airfield, with the press repeatedly branding the district as conflictive as a result (Diario Regional Aysén, 2021; Radio Las Nieves, 2019, 2023; Vega, 2018; Verdejo P., 2020). While residents acknowledge certain improvements on the island – such as increased digital connectivity, infrastructure for maritime and air connectivity, repairing the road between Melinka and Repollal, implementation of full secondary education at the high school, and a 24-hour electricity supply – it is generally considered that a number of these advances have only been possible thanks to concerted efforts on the part of local leaders, who have had to fight and be exposed to secure basic services:

I like to speak out; I like to put up a fight when there’s a good reason for it […]. The only bad thing is that you end up as the villain. The leader’s always the villain, because if some members say, “we have to speak up,” we speak up. And that figure is me (leader, September 2021).

Inhabitants of Guaitecas often seek to gain attention for local demands by skipping directly to the regional or national level in an attempt to increase visibility and exert pressure on the relevant agencies. Actions of this type are hindered by distance and cost, meaning that little time is available in which to meet with the authorities and raise or resolve their concerns. There is a perception that impact can only be achieved by leaving the island, since requirements voiced remotely tend to receive little attention and are often ignored. Thus, islandness is manifest not only in a history of unsatisfactory relations with the state, but also in the reproduction of a sense of difference from the mainland and its authorities (Bustos & Román, 2019; Mascareño et al., 2018; Parker, 2021; Vannini, 2011). On the other hand, although these escalation strategies often succeed in achieving immediate attention, they do not necessarily lead to definitive and satisfactory solutions.

7. How is the relationship with the state experienced?

Islandness is manifested in the way the role of the state is perceived: the inhabitants of Guaitecas perceive themselves as subjects with biographies characterised by their insular context, identify a predominantly unsatisfactory relationship with the state, and show initiative to organise themselves to transform this relationship. They express pride and appreciation for their home. They consider themselves hard-working, selfless, and courageous for living in the hostile environment of an island territory, but also because of their relationship with authority, marked as it is by distrust and difficulties in establishing effective communication. They highlight the capacity of locals to come together in difficult times and to support each other as a community through spontaneous initiatives that seek to remedy a specific situation, such as raising funds for medical treatment outside the district or for repairs to a neighbour’s damaged house.

At the same time, they feel that the state owes them a debt for “being here flying the flag” (district authority, October 2022) in an isolated district that itself is on the periphery of a region described institutionally as an extreme zone. The debate often becomes stuck on this point. While Guaitecas advocates for differentiated treatment in terms of access to goods and services and for flexibility in certain institutional procedures, regional authorities, and public services perceive that such assistentialism would weaken local capacity to play by the rules that govern the rest of the country:

Assistentialism. They feel that […] the country is in their debt. The region is in their debt. Chile is in their debt. So they don’t pay… they don’t pay the electricity, the water. […] Let alone licences, planning permits… nothing (municipal official, April 2022).

Those involved with politics or the institutional structure claim that Guaitecas and its peculiarities are known to regional decision-makers, who visit the district regularly. The inhabitants of Guaitecas are not shy to get involved in participatory events and discussions of the problems that afflict the community. However, because of factors relating to the bureaucracy of these processes, many such initiatives have fallen by the wayside. Those who participate feel that events of this type are useless, preferring instead to seek solutions of their own.

The size and location of the district also play a role. Its electoral impact at the regional and national level is very small: the district accounts for less than 1.5% of votes in the Aysén region, which, in turn, has the least number of voters nationally (Servicio Electoral de Chile, n.d.). This limits opportunities for parliamentary visibility and restricts the potential to influence national politics and to foster the emergence of leaders capable of generating networks of local interest outside the district. It also highlights the difficulty of sustaining development in a scenario of hyper-periphery, reproducing on every scale the gaps with the political centres and accentuating the shortcomings caused by distance (Favole & Giordana, 2018; Knoll, 2021).

As for its spatial relationship, the location of Guaitecas in the middle of the contiguous zone and surrounded by the expanding salmon industry, means that the forces in play exceed local capacities for escalation and political dialogue, putting the community at a perceived disadvantage. As a result, when faced with what they consider a threat to their interests, the inhabitants react by blockading air and sea access and preventing travel to and from the island for all but residents. In this sense, the identity element of islandness manifests itself through the generation of trust and security (Giddens, 1996; Hay, 2013; Hayward, 2012; Pugh, 2016): the exclusion of the external, even temporarily, affords a degree of control over the processes affecting the archipelago:

There is this idea that, by taking control of those access points, it is the people of Melinka versus the outsiders. […] The outsiders just look on. It is those who truly feel Melinkan that participate in those things (employee of a private company, April 2022).

Furthermore, at the local level, inhabitants perceive a lack of means and tools with which to express their needs or concerns in formal spaces of participation and negotiation, whose conditions are established by the state. This raises a barrier to participation in the discussion because local representatives often present their points of view in a forthright and emotional manner incited by the elemental nature of the demands and deficiencies that they constantly find themselves having to express. This takes a personal toll on leaders and discourages representation. Some do manage to access circles of deliberation and negotiation, but these are people whose personal characteristics and educational background enable them to speak on institutional terms, adopt its language, and observe its deadlines, acting as linkages between local demands and regional and national decision-making.

Inhabiting an island generates a complex evocation, in terms of the simultaneity of ties with the territory, that is difficult to explain to those who have no experience of daily island life (Hay, 2013; Hayward, 2012; Tuan, 2007). As such, even when islanders manage to make themselves heard by the authorities, the idea persists that they are not understood or considered and, above all, that their ideas and knowledge do not permeate the institutional structure and its instruments. Local radio and social media are important here, as they allow islanders to express themselves on their own terms.

8. Informality as a normalised practice

Although there have been significant advances in terms of decentralisation (Galilea Ocón & Letelier Saavedra, 2013; Montecinos, 2020), state intervention in Guaitecas has been top-down. Predominantly, there is effort to expand national hegemony, modifying the practices associated with a particular way of inhabiting. Adaptation to norms from an island context requires efforts and resources that depend on the capacity of each individual.

Thus, the failure of the institutional structure to deliver the necessary tools to allow inhabitants to participate fully in the country’s development – instead offering only instruments not designed for the conditions of the island setting – constitutes both a practical and ethical problem. It imposes inconveniences on daily living, preventing inhabitants from meeting certain requirements or attending to their personal needs. This is clearly evident in the case of companies, but it also affects family life when it comes to formalities, health checks, or school education:

Islandness – because I think it is characteristic of this place – determines a great many things. We have a piece of land surrounded by sea and relatively distant from the larger population centres. Distant from the opportunity structure, from access to culture, to education and to information (employee of a private company, September 2021).

In contrast, inhabitants perceive a threat to local identity and a feeling of cultural loss, particularly in relation to artisanal fishing activities and the preparation of traditional seafood dishes. Examples of this are: the shellfish bans imposed during the so-called red tide events, especially in areas with no testing facilities, the closure of the fishing register, specific requirements for artisanal fishing vessels, or the eviction of riverside carpenters from the coastline. This leads to expressions of hopelessness and frustration at inhabitants’ perceived lack of control over their own lives and their vulnerability to the designs of an external other. From there we understand the opposition to the continental as a mechanism for defining their own identity (Grydehøj, 2016). It also gives way to the normalisation of informality and to acts performed under the expectation of not being found out and penalised, because opportunities for employment, entrepreneurship, and family life are limited in the district:

Young people are disappearing, because “you have to do the course.” “You have to have your card in order to board.” “You have to have your document to hand so that we can let you sail.” […] “If we catch you, we’ll fine you.” Where is the support for citizens? (fishing leader, April 2022).

Informality emerges as a means of adapting to these gaps between regulations and the island reality for the district to continue to function despite the shortcomings. Sceptical that conditions can improve, inhabitants seek solutions with whatever is at hand. Thus, the lack of housing is addressed by means of land occupations, basic needs are covered by subsidies of different kinds, and social organisations cover more functions than they claim to cover. In conjunction with external disdain for local knowledge, opportunities are continually lost for the appropriation of instruments to make them relevant to the potential and needs of the place (Chia & Torre, 2020).

In Guaitecas there is a recent history of local management problems. Informality and adaptations can lead to bad practices, but informants refer to the need to work in a grey area when it comes to the administration of public funds and regulations. However, emphasis is usually placed on the penalisation of these adaptations (Román, 2020). Ultimately, any attempt to bring order to the various areas that have been neglected in order to comply with standards of public administration can be disruptive and cause discontent among the population.

Moreover, the state apparatus has fallen behind in its responsibility for marine management, as evidenced by recent events concerning the salmon industry (Barton & Román, 2016; Zanlungo M. et al., 2015), and has failed to treat the archipelago as a space that is both maritime and terrestrial. Furthermore, in Melinka, regulation is seen as an external menace that threatens sources of employment in a place with few options for making a living. Local institutions do not have the capacity to regulate informality, instead only managing it to ensure that it does as little harm as possible.

9. Conclusions

Our aim was to explore the consequences of inhabiting an island in observing the state and how island life affects notions of identity, politics, and territory. From there, we elaborate on a notion of islandness that allows us to access the framework that defines political positioning in centre-periphery dynamics in an insular sub-national context.

There is distance between islanders and decision-makers. This distance is both physical and technological: the separation created by the sea and restricted connectivity generates communication gaps, in media outreach, and in frequencies and opportunities for encounters. Most relevant, however, is the disconnect that occurs in relation to mutual communication and understanding. Its remoteness affects opportunities for recognition of the nature of daily life in Guaitecas at the regional and national levels. The challenges of daily life and the aspirations and development priorities of inhabitants are not channelled vertically, and priority is given to knowledge that can be easily assimilated by institutions. This results in distrust and frustration with the initiatives implemented by external authorities, reinforcing a sense of identity that frames them as inappropriate to the archipelago, and generating greater distance from the figure of the state.

In some instances, efforts to channel demands have been successful, but have come at great personal cost to leaders, who have had to strive to mobilise extensive multi-scale networks while struggling with feelings of loneliness in the role and fear of harm by the authorities. These leaders are fundamental in translating the evocative character of islandness into a language that can be understood beyond the peculiarities of their territory. They are an essential link if the aim is to reduce the gaps between centre and periphery. The relationship with the state generates complex responses that often include disappointment, resignation and resentment in the face of what is seen as inaction and a lack of appreciation for the people of Guaitecas. This stems largely from the fact that the district’s principal shortcomings correspond to basic issues considered elemental elsewhere in the country. As inhabitants of an island, they feel that they are viewed with disrespect and as different from residents of other parts of the country. The desire for recognition and respect lies at the heart of this emotional response, and the persistent lack of acceptable reactions discourages long-term work and association.

Finally, we find informality to be a critical element when it comes to reflection on island governance. In a territory of this type, resources and regulations must be managed that generally do not consider its physical and organisational characteristics or the expectations of inhabitants. Especially in a country where the population is highly concentrated in cities in a small number of regions, a district like Guaitecas is faced with a development model that is not necessarily effective. Thus, goals proposed by the state may not only be irrelevant to inhabitants, in that they fail to target the objectives important to them, but may even act against them, imposing unachievable requirements or diverting local perspectives toward an objective imposed by external forces. With this in mind, dealing with regulatory breaches requires an approach that looks beyond the punitive and the formative. What is instead required is a disaggregation of development projects to identify those goals that are relevant to the diverse territories in question, and, based on these, to rethink the rules of the game.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by ANID/FONDECYT/11200916 and ANID/FONDECYT/ 1210331. We thank those who shared with us their time and knowledge in the field. We also thank Fabiola Miranda for her support during the completion of this work, Paul Salter for his input in editing the manuscript, and the reviewers for their accurate and constructive comments.