Introduction

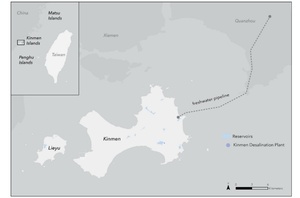

In August 2018, Taiwan’s water-stressed islands of Kinmen began receiving freshwater from the Chinese mainland through a 17-kilometer undersea pipeline. As of 2021, this pipeline provides more than 70 % of Kinmen’s drinking water (Kinmen County Waterworks, 2022, p. 14), relieving the islands’ water stress. Kinmen’s water dependence on the mainland is not an uncommon situation for islands. Many islands are subject to natural resource scarcity and often rely on nearby continents for resource provisions, such as the case of Singapore and Malaysia (though this dynamic has changed after Singapore’s development of desalination, see Usher, 2019) and the Turkey-Northern Cyprus pipeline (Mason, 2020). While Kinmen has sought to develop its own water sources by constructing reservoirs and a desalination plant, these infrastructures have failed to provide stable clean water. All the reservoirs are of poor quality, and the desalination plant operates at a low capacity due to high production costs. These challenges are familiar among many islands. For example, the operation performance of desalination has been poor in most Pacific islands due to inadequate maintenance and high operation costs (Falkland & White, 2020). In Caribbean small islands, centralized waste infrastructure is often impractical due to dispersed populations (Crisman & Winters, 2023). In all, many difficulties and failures of infrastructure are related to the unique material and social conditions of islands, such as their relatively small land mass and population, isolation from markets, and strong influences from the ocean.

To understand what and how island conditions influence water supply infrastructure, this paper engages with infrastructure literature and island studies. Recent work on infrastructure has recognized the normality of infrastructure breakdowns and failures (Schwenkel, 2015; Wakefield, 2018), attending to moments when infrastructure projects fail to perform due to the unruliness of the environment (Colven, 2020), issues with expert practices and knowledge gaps (Barry, 2013; Harvey & Knox, 2015), or a lack of maintenance and repair (Carse, 2014; Gupta, 2018). While most of these studies are not based on islands, the above conditions are common in island contexts, in part stemming from islandness characteristics. Islandness is a concept that describes the attributes that distinguish islands from other types of geographic locations, such as boundedness, remoteness, peripherality, and smallness (Baldacchino, 2006; Conkling, 2007; Foley et al., 2023; Grydehøj, 2020). Applying this idea, the insufficient maintenance on islands can be partly attributed to their relative remoteness to markets, which makes it difficult to obtain materials and technical personnel. Similarly, the inconducive island environment in relation to water infrastructure could be understood as a consequence of boundedness and smallness, which offers limited space for freshwater circulation and renders the water infrastructure more susceptible to influences from the surrounding ocean.

This paper links islandness to water supply infrastructure by asking two questions: What island conditions have contributed to the failures of Kinmen’s water infrastructure? How are these conditions related to islandness, and what are their common effects on islands’ water infrastructures? In answering these questions, the paper bridges infrastructure literature and island studies, fields that have previously exhibited limited interaction. Specifically, islands are critical sites to explore infrastructure failures, as many islands lack the material and social conditions necessary for proper infrastructure functioning. Moreover, water supply infrastructure provides a useful entry point to understand debates around islandness, as many islandness effects are particularly apparent in the case of water infrastructure. This leads to another important point, that the islandness effects are relational and meaningful within the context of water supply issues. This view is influenced by the recent ‘relational turn’ in island studies, which critiques the dichotomist and fixed perspectives on islands, stressing the importance of islands’ relationship with other islands, continents, and the ocean, as well as a more grounded and island-centered view on islands (Baldacchino, 2008; Pugh, 2016). For example, the idea of boundedness was critiqued as based on a mainland-centric perspective that sees oceans as a hard barrier, which is contested from the perspectives of islanders (Hau’ofa, 1994; Hay, 2006). In this paper, boundedness is not perceived as an inherent status of islands. Instead, the effects of boundedness are regarded as a material reality that matters to drinking water supply and is possible to be transformed by other factors. From the standpoint of water supply, the ocean does indeed create a boundary that limits the availability of freshwater on islands. Meanwhile, this effect could be altered through human intervention, such as desalination technology, which is capable of converting saltwater into freshwater. Though as demonstrated later, there are other barriers to the successful implementation of desalination on islands.

Additionally, islandness effects are not deterministic but contingent on other social and material factors, such as the geology and climatology of islands, or the island’s distance and relationship to nearby continents. For instance, although the other two offshore island groups of Taiwan – Penghu and Matsu, also suffer from water shortage due to similar island characteristics, they follow divergent modes of water supply regimes. Kinmen had relatively abundant groundwater sources due to having a larger groundwater aquifer and the privilege of buying freshwater from the Chinese mainland because of their close proximity and frequent political and social exchanges. While Matsu has also proposed to receive freshwater from the mainland, the demand for water has not been as urgent due to its small population, and its archipelagic form makes it more complicated and expensive to transfer water (Gao, 2023). Penghu, on the other hand, was not close enough to Taiwan or the continental mainland to be transported freshwater economically and had to boost its desalinated water production (Interview with technocrat, January 2022). The factors of possessing a groundwater aquifer or being close to a continent, are not commonly shared by all islands. As such, this examination considers an island’s social and material properties in relation to the ocean, other continents, and its historical contexts, while still providing generalizability and analytical value.

Island water infrastructure and islandness

Island infrastructure and infrastructure breakdown

Critical perspectives on infrastructure have underscored its capacity to reconfigure material and social relations and to serve political intentions (Anand et al., 2018; Larkin, 2013). In the context of islands, transportation infrastructures have drawn particular interest. Through materializing linkages and facilitating new material and social flows, they can significantly alter islands’ remoteness, insularity, island identity, and development trajectories (Grydehøj & Casagrande, 2020; Lee et al., 2017). Another trend of focus examines how islands became targets of geopolitical maneuvering through infrastructure. The Chinese-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) offers illustrative cases of how China has restructured or challenged the geopolitical constellation on islands (Davis et al., 2020; Rodd, 2020).

While the material and political capacities of infrastructures on islands have received ample attention, there has been a notable lack of focus on their failures, namely, instances where infrastructures do not function as planned in island contexts. In infrastructure research, scholars have acknowledged the normality of breakdown, instability, and suspension of infrastructure (Gupta, 2018; Schwenkel, 2015; Wakefield, 2018). First, biophysical environments can be ‘unruly’, introducing uncertainties and disrupting infrastructure functioning (Bakker & Bridge, 2006; Colven, 2020). Second, expert practices and knowledge production of both the environment and infrastructure can involve controversies due to the complexities of biophysical systems and the politics surrounding how and what knowledge is produced (Barry, 2013; Harvey & Knox, 2015). Lastly, infrastructure requires constant maintenance, repair, and reworking (Carse, 2014; Gupta, 2018; Ramakrishnan et al., 2021). Shortages in state care, capital, resources, or labor can impede infrastructure from being adequately maintained (Gupta, 2018; Schwenkel, 2015). In all, infrastructure does not always operate smoothly but demands supportive physical and social conditions.

The above insights hold particular significance to islands, where the physical and social environments are often inconducive to infrastructure development. For example, with small landmass and population, many islands fail to provide the conditions that water infrastructure requires, which are often bulky, high-cost, and labor-intensive (Björkman, 2015, p. 14). Moreover, being far from mainland markets can result in maintenance inconvenience (Grydehøj & Kelman, 2017; Kumar et al., 2020), and being proximate to the sea implies greater impacts from the ocean environment (Kumar et al., 2020; Radosavljevic et al., 2016). The following section engages with the idea of islandness and relational island thinking to conceptualize these island-related conditions and explore their implications on water supply infrastructure.

Islandness and relational island thinking

The concept of islandness, which can imply characteristics like smallness, boundedness, isolation, insularity, peripherality, otherness, or island culture and identity, has been a central focus of island studies (Baldacchino, 2006; Conkling, 2007; Foley et al., 2023; Grydehøj, 2020). Studies of and on islands have explored the effects of islands’ distinct (or sometimes imagined) characteristics on various aspects. In political research of islands, attributes like boundedness, remoteness, isolation, and peripherality, offer partial explanation of why many islands become sites of exception and exploitation, such as laboratories for experiments (DeLoughrey, 2012; Greenhough, 2006; Hennessy, 2018), detention centers (Bousiou, 2020; Mountz, 2011), or locations for nuclear testing and waste dumping (Baldacchino & Tsai, 2014; Davis, 2005; DeLoughrey, 2012). Studies on climate change also stress the role of peripherality in influencing climate change vulnerability and island communities’ coping capacity (McNamara et al., 2019; Nunn & Kumar, 2019). Moreover, the characteristics of smallness, boundedness, isolation, and fragmentation, can contribute to scale mismatches and data gaps in climate modeling (Foley, 2018).

While islands’ unique material form has positioned them to become a subject of inquiry, the ideas associated with islandness are by no means universal or coherent. Instead, islandness is experienced differently, and island-related characteristics are relative in many senses, depending on viewers’ perspectives as well as other social and physical factors. For example, the idea of boundedness may not apply to an islander who sees the sea as resourceful rather than a barrier (Hau’ofa, 1994). Meanwhile, other factors like transportation infrastructure, can significantly alter an island’s level of isolation and remoteness, or even reshape island identity (Grydehøj & Casagrande, 2020; Scanlon, 2024). Many have also contested the view of smallness, suggesting that small is often context-dependent and produced (Foley et al., 2023; Nimführ & Otto, 2021), which can render islands vulnerable (Kelman, 2018). The relational turn in island studies, such as the archipelagic, ‘aquapelagic’, or ‘islandscape’ approaches, have attempted to revoke the pre-assumed characterizations of islands and the dualistic view of island/continent and land/sea (Hayward, 2012; Nimführ & Otto, 2020; Pugh, 2013; Stratford et al., 2011). The important insight here is not to treat islands or island-specific characteristics as static or given but as practiced and in relation to other continents, oceans, and islands.

Islandness and island water supply infrastructure

Incorporating insights from infrastructure literature and island studies, this paper seeks to understand failures of island water supply infrastructure through the lens of islandness and relational island thinking. To be sure, previous studies have identified various challenges in islands’ water resources and governance. Islands have limited surface freshwater, and the freshwater is often prone to seawater intrusion (Sharan et al., 2021; Werner et al., 2017; White & Falkland, 2010). In addition to environmental constraints in freshwater availability, many islands are also found to possess governance issues (Belmar et al., 2016; Cashman, 2014; Mateus et al., 2020; Mycoo, 2018). For example, Belmar et al. (2016) observed that the traditional command and control paradigm of water management works poorly in island contexts due to human resources constraints, limited science and technical capacity, high costs and maintenance of infrastructure, and strong patron-client relationships. Cashman (2014) highlights a lack of data to be the main barrier to water security in the Caribbean. These challenges identified in the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are of high similarity to the Kinmen Islands, suggesting that despite their differences in locations, geology, and socio-economic contexts, islands share similar conditions that pose challenges to water supply. However, the relationships between islandness and water supply infrastructure remain under-conceptualized.

Though not directly focused on water, an overall examination of the role of islandness on islands’ socio-ecological systems can be found in Nel et al. (2021). They see islandness as a fundamental element that “materializes socio-ecological islandscapes” by testing the influences of islandness through variables such as isolation, island size, number of inhabited islands, and shipping connectivity. Their attempt successfully demonstrates the role of islandness in shaping social and ecological components of island systems through a quantitative evaluation. However, this approach focuses on which variables matter more than the others and does not explain how and why these variables are at play. Besides, extensive data collection and variables across multiple islands in consistent formats are required for the model to be effective, and as mentioned, such data is often lacking on islands (Cashman, 2014; Foley, 2018). With a similar inquiry but a different approach, this paper analyzes the effects of islandness on water supply infrastructure through case study and document analysis. In doing so, it offers specific insights into how and why water infrastructure failed to function properly on islands. Importantly, the islandness factors identified in this paper are not considered as possessing determining effects but are contingent upon other factors and matter specifically to water supply infrastructure. For instance, the smallness and boundedness of an island create a set of material conditions that make it challenging to capture and preserve freshwater. But this effect is also attributed to other factors – flat topography adds to the difficulties of circulating water, and population, as well their perceived need, determines whether there is ‘enough’ water. The idea of ‘smallness’ per se, is also a characterization based on the standpoint of water provision. An island is small in the sense that it does not provide enough catchment area to preserve water. As such, the effects of smallness on islands’ water infrastructure are examined with a recognition that ‘small’ is only one of the conditions that cause challenges, and that ‘small’ is not intrinsic but a relative idea.

Materials and methods

Kinmen Islands and water supply

The Islands of Kinmen constitute a group of twelve islands with a total area of 151.66 km2. The majority of the land area and population are concentrated on Kinmen main island and Lieyu (also known as little Kinmen). While the registered population of Kinmen is around 140,000, the actual population residing on the islands is estimated by most villagers to be only around 50,000 to 70,000, as many people currently live in Taiwan main island but keep their households registered in Kinmen to continue receiving social benefits provided by the Kinmen County Government (Interview with villagers, 2021-22).

Located less than 5 km off the coast of the mainland of Southeast China and 200 km from Taiwan, the islands historically had frequent exchanges with the Chinese mainland. However, since the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan in 1949, Kinmen became a military frontline against Communist China. During this period, most of the reservoirs, irrigation dams, groundwater wells, and centralized water supply systems were established to support the influx of military population. After forty years of militarization and isolation, the islands’ military status was lifted in the 1990s. In the 2000s, communications between Kinmen and the mainland were resumed under a policy called Mini-Three-Link, allowing direct exchanges between the islands and the Chinese mainland. The frequent interaction facilitated the idea of a cross-border freshwater pipeline, which was realized in 2018 and has since become the main source of water supply for the islands (see Figures 1 and 2).

The public water supply on the islands is operated by the Kinmen County Waterworks (KCW), a local government entity that is also responsible for managing the islands’ water infrastructure and sewage. Over the past decade, the KCW provided approximately 7.5 million m3 of water annually (Kinmen County Waterworks, 2018, 2022). In addition to residential and public water consumption, the water supply also plays a crucial role in supporting the island’s two main industries: tourism, which attracts 1.5 million tourists annually, and the sorghum liquor distilling industry, contributing more than half of the income for the Kinmen County Government.

Before Kinmen began receiving freshwater from the mainland in 2018, groundwater and surface water accounted for about 58% and 40%, respectively, of its water supply, with only 2% coming from desalination (Kinmen County Waterworks, 2018; refer to Figure 2). The western part of Kinmen benefits from a groundwater aquifer with a maximum thickness exceeding 100 m (Liu et al., 2008), providing the area with potable groundwater for public supply and sorghum liquor distilleries. In contrast, the eastern part of the islands lacks abundant and clean groundwater, relying instead on reservoirs to capture rainwater (see Figure 1 for locations of reservoirs). However, the water in these reservoirs constantly falls below drinking water quality standards and requires advanced treatment. The reservoirs are susceptible to pollution, given their small size and proximity to settlements. Despite an average annual precipitation of around 1,100 mm, uneven temporal distribution of rainfall and a high evaporation rate pose challenges for creating enough runoff to replenish freshwater in the reservoirs (Kinmen County Agricultural Research Institute, 2019; interview with technocrats, January and April 2022). Meanwhile, the KCW has sought to utilize seawater through desalination, but the islands’ limited technological capacity and poor seawater quality in the area have hindered successful and economical utilization of desalinated water. Although the islands’ water stress has been alleviated with the current supply of 70% of its freshwater from the mainland, the ongoing tensions between Taiwan and the Chinese mainland may cause potential disruptions to this cross-border water source. As such, securing 70% of the islands’ own water sources remains a crucial objective, particularly from the standpoint of Taiwan’s central government (Interview with technocrat and government official, January 2022, June 2023). Therefore, it is necessary to explore the challenges faced by water infrastructure on the islands.

Methods

This research is based on a case study of failing water infrastructures in Kinmen and a document analysis of water supply on Taiwan’s offshore islands. The analysis draws from two primary sources – documents and interviews. The first source includes technical reports, policy documents, news media, and council records related to water supply and infrastructure on the Kinmen Islands, along with Taiwan’s other two major offshore island groups – Penghu and Matsu. The reason for including data on the other two islands is to identify both similar islandness effects and differing conditions shaped by relational factors, such as archipelagic forms, seawater quality, and their varying relationships with the continental mainland.

The second set of data was collected during twelve months of fieldwork in Kinmen and Taiwan between October 2021 and September 2023. The fieldwork consisted of 52 key informant interviews and informal conversations with government officials, technocrats, technical staff, contractors, scholars, and island residents. Respondents were identified either through local introductions or by directly contacting individuals listed on agency websites. The author is a graduate student from Taiwan studying at a US university. This positionality is generally welcomed by the government agencies in Kinmen and Taiwan, which helps facilitate access to interviews.

The document and interview data were analyzed to (1) understand how water infrastructure projects in Kinmen have failed; and to (2) identify factors related to islands that are being discussed as having an impact on water infrastructures. These factors were coded and analyzed using NVivo software. For example, “smallness” as a constraint on water supply was mentioned by 13 interviewees and in 10 technical reports, thus being identified as a critical islandness factor. These factors were then grouped into three categories, and their various impacts were discussed in terms of how they influence the water infrastructure in Kinmen and the other two islands.

Water supply infrastructure failures in Kinmen

Eutrophicated and salinized reservoirs

There are thirteen drinking water reservoirs in Kinmen, with ten located in the eastern part of Kinmen and three in Lieyu. The reservoirs used to contribute 40% of the public water supply, but this number has plummeted to 3% in 2021, as Kinmen currently relies on the mainland for 70% of its water supply (refer to figure 2). The reservoir water has been unfavored because of its poor quality. All the reservoirs in Kinmen have long been in a state of eutrophication (Meng, 2002). From 2011 to 2020, the average Carlson trophic state index (CTSI) for those reservoirs was 67.43 (National Taipei University of Technology, 2021, p. 190), falling on the higher end of the eutrophic range (CTSI between 50 and 70). At times, certain reservoirs were tested hypereutrophic, with the highest CTSI number being 91.34 (National Taipei University of Technology, 2021, p. 190).

The crisis of poor water quality in the reservoirs reached its peak in 2011 when residents in eastern Kinmen discovered a type of sewage worm (Tubifex hattai) coming out of their tap water. To address this issue, the Kinmen County Government and Taiwan’s central water planning agency, the Water Resources Agency (WRA), formed an emergency response team. Besides efforts to enhance and improve the water treatment process, they installed water tanks with advanced treated water at the entrance of every village in the eastern part of the island as a substitute for tap water supply (shown in Figure 3). Since then, residents in eastern Kinmen began retrieving drinking and cooking water from these public water tanks. Nowadays, despite the resolution of the worm issue and warnings from the KCW that water in the tanks is not necessarily better or different from tap water, most residents continue to hold a distrust of tap water and persist in the habit of obtaining water from the tanks (expressed by at least ten Kinmen’s residents in personal conversations, 2021-23).

The deterioration of reservoir quality in Kinmen can be attributed to multiple factors, but most of my interviewees and technical reports emphasized the limitations imposed by island conditions – of being small and bounded by the ocean. On the Kinmen Islands, streams are short and catchment areas are small, posing difficulties in maintaining constant streamflow and water quality. A technocrat from the WRA remarked that Kinmen’s reservoirs should rather be called small ponds (Interview with technocrat, May 2023). Indeed, the average reservoir size is 0.46 million-m3 in Kinmen, which is more than 140 times smaller than the average size of 65.29 million-m3 on Taiwan main island (Water Resources Agency, 2021). Although the idea of ‘small’ is relative, and the islands’ smaller population implies less water needs, the problem is that smaller reservoirs tend to accumulate nutrients more easily due to reduced turnover and circulation. Without sufficient rainfall to replenish the water and with exposure to the sun, the water quality deteriorates rapidly.

Due to the small size of the islands combined with a lack of mountains, it is hard to find ideal locations to construct reservoirs that have large enough catchment areas and buffer zones from human activities. Many reservoirs are built downstream to have larger storage potential (Interview with technocrat, November 2021). However, this increases their vulnerability to nutrient runoff, wastewater, and sometimes seawater intrusion. Some reservoirs located adjacent to villages are affected by pollution from wastewater and farming activities, and two downstream reservoirs have encountered issues of salinization. Notably, Jinhu Reservoir experienced seawater intrusion 34 times within only five months immediately following the completion of construction (Control Yuan, 2011, p. 6). The 6.3 billion TWD (approximately 20.3 million USD) reservoir has never been able to fulfill its intended purpose of providing drinking water.

The accumulation of nutrients or salinity in reservoirs has also increased difficulties in treatment processes and thus led to higher material and maintenance costs (Tamkang University, 2015, p. 65). In Kinmen, water treatment plants on the eastern island have had to implement advanced treatment units with reverse osmosis (RO) technologies, which significantly elevates the cost of producing water. Moreover, these treatment plants were designed to process multiple sources of water, and due to the unstable quantity and quality of different water resources, the treatment process becomes more complicated given the need to constantly switch treatment approaches based on their differing treatment needs, including chemical usage (Interview with contractor, May 2022). The lack of professional personnel and extended transportation time for technical parts to arrive on the islands, further compounds the challenges in supplying drinking water (Interview with contractor, May 2022).

Malfunctioned and costly desalination

As concerns grew over the declining quality of reservoir water, authorities in Kinmen and the WRA began exploring alternative water sources in the 1990s. Desalination emerged as a potential solution for the islands that lack clean freshwater resources. However, it did not turn out as expected and instead demonstrated several challenges, including underqualified contractors, a high malfunction rate, and substantial energy demand and production costs.

To begin with, the construction of the desalination plant in Kinmen was not smooth. The project first started in 1998, with an anticipated completion date within the year followed by a year of trial run. However, it ended up taking seven years to complete. During the trial period, it was discovered that the system was experiencing multiple equipment malfunctions, and some necessary technical parts were even missing (Taipei Iron Works, 2005). The pretreatment facility was unable to properly process the low-quality source seawater, leading to malfunctions and fouling of the RO system (Central Region Water Resources Office, WRA, 2016, pp. 32–34). When the desalination plant finally began operation in 2004, it could only produce 1,000 cubic meters per day (CMD), half of its designed capacity of 2,000 CMD. The plant’s RO recovery rate was 25%, much lower than the typical rate of 35-45% (Control Yuan, 2012, p. 11). Its average production from 2004 to 2015 was 713CMD (refer to Figure 2), accounting for less than 4% of the total water supply in Kinmen (Environmental & Infrastructural Technologies, 2010, pp. 3–15; Kinmen County Waterworks, 2015, 2018).

The technical failures and construction delays can be largely attributed to the underqualification of the contracted companies and the inexperience with desalination technology at the time of construction (Li, 2006; RSEA Engineering Corporation, 2005). This experience was not exclusive to Kinmen. The desalination plants built in the early 2000s on Taiwan’s offshore islands presented a series of issues caused by poor design and exacerbated by a lack of proper maintenance due to the islands’ remote locations or damage caused by typhoons and waves (Chen, 2017; LotSoar Consultants, 2015; Yang et al., 2012). Many of these plants failed to perform at their designed production levels and some quit running after only one to three years of operation. About 6 desalination plants (out of 8) built in this period had serious issues (including the Kinmen Desalination Plant) that the local county governments and the WRA have received corrective measures from the national ombudsman institution of Taiwan (Control Yuan, 2005, 2009, 2012).

These unsuccessful experiences illustrate the challenges of building and operating advanced infrastructure on islands. The high expenses of constructing desalination plants on offshore islands, combined with the common practice of governments to adopt lowest cost bidders and short-term contracts, often resulted in no qualified contractors with the high technical requirements willing to undertake projects on islands (Control Yuan, 2012, p. 14; Environmental & Infrastructural Technologies, 2010, pp. 14–4; Interview with contractor, May 2022). Several companies could not achieve contract requirements and had to quit the projects due to their financial loss or incapability to complete the construction (Control Yuan, 2008; RSEA Engineering Corporation, 2005). Some individual desalination projects were divided into parts sub-contracted to multiple companies, later leading to incompatible integration (Control Yuan, 2012, p. 16). A desalination project planned for Kinmen’s offshore island Lieyu was canceled after four rounds of bidding, as no contractors were willing to bid on the project due to its perceived lack of profitability (Control Yuan, 2012, p. 25).

Besides contractors’ issues, the poor and high variation of seawater quality around Kinmen was a common explanation for the plant’s unsuccessfulness. Located at the estuary of Xiamen, the seawater near Kinmen receives discharges from the megacity with a population of 5.3 million, resulting in its high turbidity (Interview with technocrats, November 2021, March and April 2022, May 2023). During the trial period, the turbidity of the intake water ranged from 4.17 to 212 NTU (Central Region Water Resources Office, WRA, 2016, p. 32) consistently remaining above the recommended value of 4 and often exceeding the maximum threshold of 6. With such high turbidity levels, the pretreatment facility was unable to effectively remove particles from the source seawater, which then clogged the RO system quickly, affecting its performance. In addition, the total dissolved solids (TDS, a measure of organic and inorganic materials dissolved in the water) of the source seawater fluctuated from 33,200 mg/L to 45,800 mg/L, while the plant’s designed threshold was 39,000 mg/L (Central Region Water Resources Office, WRA, 2016, pp. 17–18). The high TDS concentration could result in increased osmotic pressure, leading to elevated energy consumption.

Energy is another crucial factor in the operation of desalination plants. As noted by a technocrat, desalination is an exchange of energy for water (Interview with technocrat, November 2021). The typical energy demand for seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) is in the range of 4 to 6 kWh/m3 (Al-Karaghouli & Kazmerski, 2013, p. 347). In Kinmen’s case, this figure was 10 kWh/m3 due to its small production size, the poor quality of the source seawater, and the reduced performance of the RO system (Central Region Water Resources Office, WRA, 2016, p. 34). The energy consumption of the desalination plant was four to ten times higher than that of the reservoir water treatment plants (Song, 2015, pp. 5–19). This high energy demand presents a significant challenge for the islands, where 97% of the energy depends on imported fuel, and the cost of energy production is also higher than in Taiwan (Taiwan Power Company, 2022).

Even after the desalination plant was remodeled in 2018, which included replacing the conventional sand filtration system with an ultra-filtration (UF) system and expanding the production capacity from 2,000 CMD to 4,000CMD, the production of desalinated water has remained low owing to high treatment costs. The cost ranges from 0.92 to 2.2 USD/m3, depending on the scale of production (Central Region Water Resources Office, WRA, 2018, p. 154). This cost does not include the construction or energy costs, which are covered by an offshore islands’ development fund. To make a desalination plant cost-effective, the production scale must increase. Yet the contradiction is that the KCW is hesitant to increase desalinated water production due to its relatively high cost, especially when other water sources are available (Interview with technocrat, November 2021). Since Kinmen began buying water from the mainland in 2018, it is unlikely that the production scale of desalination on the islands will increase in the near future. Currently, desalination water is considered as a ‘back-up’ water source, and Kinmen’s dependence on water from the mainland has, in a way, undermined its motivation to enhance local water production.

Discussion: Islandness and water supply infrastructure

In the cases of reservoirs and the desalination plant in Kinmen, some islandness effects on water supply and infrastructure were brought up in my conversations with the technocrats. These issues were not exclusive to Kinmen but were also commonly mentioned in water infrastructure planning reports on Taiwan’s offshore islands. In this section, the islandness effects are categorized as related to (1) smallness; (2) remoteness and peripherality; and (3) ocean materiality. The discussion delves into multiple ways these factors affect (or are perceived to affect) island water supply infrastructures.

Smallness: small water storage capacity and small production scales

Technocrats and technical reports have consistently highlighted smallness as the main constraint, creating both physical and social conditions that are unfavorable for water supply infrastructure. The most mentioned hydrological and infrastructural disadvantage resulting from the small size of islands is having relatively short or no streams and small freshwater storage, which can lead to challenges in capturing water and maintaining water quality. The small size of reservoirs, compounded with little rainfall and streamflow to replenish the water and close proximity to the ocean and human settlements, keep the reservoir water constantly in poor quality condition. This is not just the case in Kinmen – the other two offshore island groups in Taiwan are smaller in size and have no apparent stream, resulting in similarly poor reservoir quality. Out of the 26 reservoirs across the three islands, 25 are eutrophicated (National Taipei University of Technology, 2021, pp. 19, 219). A report reviewing reservoir quality management standards in Taiwan concludes that it is practically challenging for reservoirs on the offshore islands to achieve drinking water quality standards and suggests adopting a different water quality measure for offshore islands (National Taipei University of Technology, 2021, p. 209).

On the other hand, the social-economic effect of smallness is the difficulty of achieving an economic scale of infrastructure service provisions (Kumar et al., 2020), leading to a higher cost of producing water and a lack of investment interests for professional contracting companies (Environmental & Infrastructural Technologies, 2010, pp. 14–4; Interview with contractor and technocrat, May 2022, May 2023). Compared to water provision networks in Taiwan, water supply systems on Kinmen and other offshore islands serve fewer households, and water treatment plants are more dispersed, resulting in higher management and production costs (Lo, 2015, p. 51; National Chiao Tung University, 2015, pp. 5–8). A contractor highlighted the stark contrast that the water production in another treatment plant in Taiwan is fifty times more than that of the plant in Kinmen, leading to much lower management costs (Interview with contractor, May 2022). The challenge to achieve an economic scale is especially the case for desalination, which costs significantly more when produced on a small scale. Comparing two desalination plants in the Penghu Archipelago, the water production cost for the 4,000 CMD plant on Penghu’s main island is about $1.76 USD/m3 while the cost for a 400 CMD plant on Penghu’s offshore island rises to $3.87 USD/m3 (Executive Yuan, 2019, p. A-17; applying an exchange rate of 0.032). Contradictorily, smaller islands often have no choice but to rely on desalinated water due to the scarcity of freshwater (Interview with technocrat, May 2023).

Remoteness and peripherality: low technical capability

Islands are often perceived as relatively remote and peripheral. Despite this view being mainland-centric (Hau’ofa, 1994; Ronström, 2021), and recognizing that the level of remoteness and peripherality can be changed by transportation infrastructure (Grydehøj & Casagrande, 2020; Leung et al., 2017), many islands are distant from terrestrial resources and markets. This geographical condition can result in low technical capability, making it difficult to operate and maintain centralized modern water supply systems.

Peripherality can lead to a lack of data, which has been identified as a recurring issue on the offshore islands of Taiwan (e.g. Environmental & Infrastructural Technologies, 2007, 2010). The environmental data collection in Kinmen and Matsu began much later than in Taiwan main island, due to the two islands being peripheral and the limitation from militarization (Interview with technocrat, December 2021; LotSoar Consultants, 2015, pp. 2–1). Take weather data for example, while the first weather stations in Taiwan main island and Penghu were established as early as in 1896, it was not until 2003 that the Central Weather Bureau of Taiwan established weather stations in Kinmen and Matsu (Central Weather Administration, n.d.-a, n.d.-b). Before this, only basic weather information such as temperature and precipitation was recorded. Moreover, in Kinmen’s case, some early data was inaccurate or even fabricated (Interview with technocrats, December 2021, April 2022).

On the other hand, global big data often does not apply well to island-scale analysis (Foley, 2018). A scholar mentioned that it is extremely difficult to model climate change’s impacts on Kinmen due to the mismatched scale of global data, though the islands may be the earliest to experience sea level rising (Interview with scholar, July 2023). This is similar to what Foley (2018) has observed in the SIDS – when applying global data, the gird cells of islands are sometimes incorrectly characterized due to the smallness of islands, and the spatial gaps of data can be large due to the fragmentation of islands. The absence of comprehensive and fine-scale data has contributed to problematic design and planning of infrastructure projects, as big water infrastructure is often grounded in western scientific and statist information (Birkenholtz, 2023). For example, the limited tidal data in part resulted in the improper design of Jinhu reservoir, leading to immediate seawater intrusion (Control Yuan, 2012). Similarly, a lack of marine data collection caused issues in the construction of Kinmen desalination plant (RSEA Engineering Corporation, 2005). These two cases also underscore a general absence of marine data, which is attributed to the governments’ peripheral attention to the marine environment (Interview with technocrat, December 2021).

The senses of peripherality and remoteness have also deterred professionals or contractors from working on islands. A management head at a water treatment plant in Kinmen expressed the difficulty of finding professional personnel to work on the offshore islands. A job post was opened for two years without any applicants (Interview with contractor, May 2022). For some who are willing to work on offshore islands, there were complaints toward them, suggesting that they put less care towards work and do not remember things they were taught to do, because “the sky is high, the emperor is far away” (Tian gao huangdi yuan, a Chinese saying meaning being remote from the central government and thus beyond its control; interview with scholar, January 2022). This phenomenon was observed in Matsu as well, as a report suggested that the staff lacked training and there was a lack of expertise when it came to determining proper chemical amounts, ratios and timing for treatment (National Chiao Tung University, 2015, pp. 3–3). So too, there is little incentive for contracting companies to invest in maintenance enhancement due to short-term operations (National Chiao Tung University, 2015, pp. 3–10). Profit margins are lower on islands compared to mainland areas as it takes more time and money to order and ship materials to islands (Interview with contractor, May 2022). While infrastructure scholars have emphasized the importance of maintenance (Carse, 2014; Ramakrishnan et al., 2021), the shortage of technical labor and care due to their relative peripherality, coupled with challenges in obtaining land-based resources because of remoteness, can impede infrastructure maintenance and the successful operation of infrastructure on islands.

Additionally, the low technical capability coupled with smallness has also created obstacles in enhancing energy security. Over 95% of the energy generated on the offshore islands of Taiwan comes from imported fuel (Taiwan Power Company, 2022), which is not only non-local but also carbon-intensive and uneconomical. Although there has been some progress in renewable energy, achieving energy self-sufficiency on small islands remains challenging due to limited space for land-based renewable energy (Grydehøj & Kelman, 2017), low economic feasibility from small-scale production (Iy-Hsing Engineering Consultants, Inc., 2007, p. 4-5), and the lack of grid connections and storage capacity (Cho et al., 2021; Nordman et al., 2019).

Ocean materiality: material impacts on infrastructure

Another crucial material condition of islands is that they are bounded by and proximate to the ocean. The infrastructures on islands are therefore susceptible to various impacts associated with the ocean. First, islands’ water resources are exposed to salinization, which can occur through seawater intrusion or leaching of residual saline water from the marine sedimentary environment (Mirzavand et al., 2020, p. 2465). Salinization has affected both groundwater aquifers and reservoirs on Taiwan’s offshore islands (Jang et al., 2012; Liou et al., 2009; LotSoar Consultants, 2015). In Penghu, all the groundwater wells were tested high in electrical conductivity (EC) and total dissolved solids (TDS) (NCKU Research and Development Foundation, 2016, pp. 26–27). The prevalence of salinization on islands is also attributed to their small size, offering limited buffer distances for surface and groundwater aquifers to be protected from ocean influence.

Marine weather conditions have frequently affected offshore water infrastructure construction, maintenance, and transportation of materials. During construction phases, strong wind and waves in winter and typhoon seasons can pose difficulties, causing delays in the cases of desalination plants in Kinmen and Matsu (Environmental & Infrastructural Technologies, 2010, pp. 6–27; Kinmen County Council, 2000). In worse case scenarios, typhoons have caused breakdowns and damage to water infrastructures. Although damage from typhoons is not exclusive to islands, their recovery time is often longer due to the lack of alternative energy sources, technical capacities, and transportation inconveniences. For example, during Typhoon Meranti in 2016, Kinmen experienced power breakdowns, water treatment plant shutdowns, and difficulties in repairing and replacing damaged components due to transportation disruptions (Interview with contractor, May 2022). Together, the strong influences from the ocean environment and marine weather conditions can make islands ‘unruly’ to the operation of advanced water supply infrastructure.

Lastly, despite advancements in desalination technology, seawater quality can significantly determine the viability of utilizing it as an alternative water source. Technical challenges aside, poor seawater quality, characterized by high turbidity or the presence of specific types of algae, can exceed the processing capacity of desalination facilities, leading to elevated electricity demand and sometimes malfunctions or failures (Interview with contractor, May 2022). The high turbidity of seawater around Kinmen caused the breakdown of infrastructure and prevented water production from being economical. This fluctuating seawater quality near Kinmen is often attributed to its location at the estuary of Xiamen. Compared to Kinmen, the Penghu Islands, being farther from densely populated mainland areas or islands, have cleaner seawater that enables smoother desalination operations (Interview with technocrats, November 2021, March and April 2022, May 2023). These differences suggest that ocean materiality is dependent on an island’s location and its relation to other continents or islands. The materiality of the seawater near Kinmen, influenced by its proximity to Xiamen, is a relational factor that has, in part, determined the feasibility of desalination.

Conclusions

Research on infrastructure has attended to the instances where infrastructure does not operate as planned, highlighting factors such as uncooperative environments (Bakker & Bridge, 2006), complexities in knowledge and expert practices (Harvey & Knox, 2015), and a lack of maintenance and care (Carse, 2014; Gupta, 2018). This research suggests that these conditions are often commonly experienced on islands due to effects of islandness. Specifically, islands can be unruly to the functioning of big water infrastructure due to their smallness and susceptibility to strong material influences from the ocean. Additionally, the remoteness and peripherality of islands create socio-material conditions that make infrastructural maintenance and knowledge production challenging, which are often critical for successful infrastructure planning and operation. These challenges faced by the reservoirs and the desalination plant in Kinmen are also observable in other offshore islands of Taiwan and islands in different regions (e.g. Mateus et al., 2020; Sharan et al., 2021), indicating a degree of generalizability of islandness effects on water infrastructures.

However, it is crucial to recognize that these conditions are not inherent or fixed; rather, they are relational and contingent upon other factors. The small size of reservoirs, for instance, does not necessarily result in insufficient water but depends on climate and geological factors. Similarly, low technical capacity may not be the case for islands with enhanced connectivity or could be improved through policy implementation. Singapore’s success with desalination suggests that small island nations can achieve high technical capability, not only due to effective policies but also because the islandness attributes associated with low technical capability – remoteness and peripherality, do not apply to Singapore. Furthermore, while islands may share many common conditions, their overall water supply scenarios can vary. Comparing Taiwan’ offshore islands – Kinmen has the options of utilizing groundwater and freshwater from the Chinese mainland, whereas Matsu and Penghu have to rely heavily on desalination water due to the lack of alternative options. Additionally, the individual islets within the three island groups show varying water supply conditions.

Despite different modes of water supply, the findings indicate that the necessary conditions for advanced and centralized infrastructures are often deficient on islands. This is not just the case for desalination and reservoirs, but also for other infrastructures such as wastewater systems and submarine pipelines, as there is evidence of failures in those infrastructures in Kinmen and other islands. However, while islandness creates specific challenges for water infrastructure, islands are also the most in need of water resources. The three offshore island groups were among the earliest in Taiwan that have adopted desalination technology for public water supply, driven by their limited alternative water resources. This underscores a dilemma for islands, emphasizing the need for further research and efforts to gain a deeper understanding of resources and infrastructure on islands.

Acknolwedgment

I would like to thank Dr. Trevor Birkenholtz, the Nature Society Working Group at Penn State, and the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. I am also grateful to the interview respondents who made this research possible. The research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council National Science Foundation - National Research Trainee Program LandscapeU Grant [DGE 1828822] and the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)