1. Introduction

Commonwealth Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are broadly recognised as facing considerable challenges in accessing finance for climate change adaptation or for projects to pursue the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) (United Nations, 2023; Kattumuri, 2023). Public sector financial support from bilateral and multilateral sources is provided predominantly as debt finance, leading to substantial debt burdens and risks of debt stress (International Development Committee, House of Commons, 2023; Piemonte, 2022). Despite SIDS receiving a rising share of public sector climate finance (Piemonte, 2022), access to these funds is uneven, and the overall volume remains insufficient (Robinson & Dornan, 2017).

Securing stable investment is now considered key to SIDS’ future development but is impeded by perceptions that SIDS are ‘too risky’ due to internal and structural factors in the country. These include high costs, poor and slow decision-making, corruption, lack of economies of scale, exposure to natural disasters, and perceived inadequacy of a robust pipeline of ‘investable projects’ (Ameli et al., 2021; Kattumuri, 2023; UNESCAP, 2019). In response, previous scholarship and policy work on SIDS finance emphasised the quality of domestic governance in SIDS as the primary factor for derisking investment, and consequently attracting private sector finance (Dornan, 2015; UNESCAP, 2019). Despite significant investment in governance capacity building, investment in SIDS remains inadequate (The Commonwealth, 2021).

As a counter to this narrative, recent discourses within multilateral forums have reframed the challenges in attracting investment not as domestic governance failings but as a consequence of the design of the international public multilateral financial system or the private sector financial industry (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2023; UN OHRLLS, 2022). As an illustration, in April 2023, Barbados Prime Minister Mia Motley expressed:

The world is running out of time to fix its international financial system that is broken, outdated, infested with short termism and downright unfair. Too many countries are being prevented from fighting the climate crisis and from creating decent opportunities for billions of people – their citizens (. …) either we proceed with the status quo, which will lead to a decoupling of the international financial system from developing economies, or we can adapt the current system to the present world. (United Nations, 2023, p. 1)

Existing mechanisms to support SIDS with climate finance, such as the Green Climate Fund, have faced criticism for their complex accessibility requirements, bias towards largeness, and reliance on loan instruments that exacerbate existing indebtedness (Treichel et al., 2024). Moreover, equivalent funding mechanisms for non-climate-related development have yet to emerge for SIDS (Habib et al., 2024).

We contribute to this ongoing discourse by introducing a novel institutional model for systemic risk governance that will provide an alternative pathway—a financial system adaptation—for SIDS to access finance for climate mitigation/adaption and more generally. The core principle of this model, called the Common Pool Asset Structuring System (COMPASS), is to recognise the common challenges faced by SIDS, and the similar types of assets they hold, and use these insights to build investable portfolios of projects alongside proactive strategies to derisk the investment process for all stakeholders in the investment cycle. COMPASS is designed to attract multiple types of finance (public, private, and philanthropic) either singularly or in combination as blended finance, depending on project and user needs.

COMPASS was developed as part of a broader action-research collaboration between the authors and the Commonwealth Secretariat in support of their 23 SIDS members and the challenges they face arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change. While Commonwealth SIDS are diverse in size, geography, culture, and levels of economic development, this research was driven by the insight that they share similar challenges in accessing international finance. This research explored the question: How can we transform the capacity of governments in SIDS to attract sustainable finance to contribute to resilient economies?

COMPASS has been presented to the policy community through a series of policy briefing notes (Habib et al., 2024). This paper establishes a theoretical and conceptual foundation for COMPASS and demonstrates its underlying principles and logic. In the remainder of the paper, we focus on accessing finance of any type for SIDS members of the Commonwealth only, while acknowledging that the issues raised, and COMPASS, has broader application to other SIDS and small states.

In addition, this paper makes three key contributions to the literature and policy discourse. First, we briefly review the technical and governance literature on risk management, focussing on its application to SIDS to explore the ‘under investment trap’ faced by SIDS (Ameli et al., 2021). To better understand why this underinvestment persists, we critique the current policy proscriptions for overcoming this trap and extend the neoclassical perspective on risks/barriers (Dandage et al., 2018; Yaqoot et al., 2016) to incorporate political-economic and systems-based variables to provide a more context specific and richer account for the phenomenon. We, therefore, incorporate into the barrier-risk relationship key ideas from complexity and institutional economics (Arthur, 2021; Ostrom, 1990, 2005) transition studies (Geels, 2011) and sustainability science (Wyborn et al., 2019) to include ideas such as the importance of transition and cultural context, changing power relations, bio-geography, climate change, and social justice as part of the story in explaining the risks and barriers inherent in private sector investment in SIDS.

Secondly, using investment in marine renewable energy (MRE) as an illustrative example, we employ our critique to develop a typology of specific structural, operational, and transitional system level risks (Dandage et al., 2018) faced by SIDS governments and investors, beyond the standard range of investment risks. This highlights both the governmental perspective under explored in the literature and provides a more holistic understanding of the challenges faced by SIDS.

Third, we contend that these challenges require de-risking through innovations in risk governance. Drawing on collective action theory (Ostrom, 1990) and the historical precedents of collaboration between SIDS, we present and discuss the COMPASS model. In addition to delivering finance for SIDS, COMPASS is also designed to deliver investors a portfolio of SIDS projects with overall net positive benefits and thereby opens up new markets for impact and SDG-themed investments.

This paper is organised as follows. Section two revisits mainstream critiques of why SIDS struggle to attract investment. While recognising that the mainstream arguments around governance still hold, this section uses a systems-based approach to present a broader interpretation. Section three discusses the system level risks facing SIDS governments and investors linked with existing investment approaches. In section four, we consider whether conventional approaches to risk management developed in the global north could be adapted as de-risking strategies for SIDS before presenting COMPASS in Section five. Section six concludes this paper.

2. Revisiting the Literature on SIDS as a ‘Risky Investment’

The challenge of SIDS in accessing finance is extensively discussed in scholarly and policy literature. The prevailing narrative is that most, but not all, SIDS are “too risky” for private sector investors and, therefore, have limited capacity to attract funding beyond the public sector (UNESCAP, 2019).

There are two broad themes that provide a framework for understanding this phenomenon.

Both mainstream neoclassical and behavioural finance literature (Ramiah et al., 2015; Sharpe, 1964; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974) frame the problem of investment risk management as a technical exercise involving the evaluation and choice of alternative asset valuation models (Fama & French, 2006; Villadsen et al., 2017) and a debate over the selection of input parameters. Investment decisions are driven by perceptions of future risk levels and expected profitability, incorporating reputational, market, credit, and project risks (Demirel et al., 2022; Schmidt, 2014). Implicit is the notion that if the asset pricing and the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) appropriately reflect the risks involved in the investment, then decision-makers possess the requisite information to formulate rational investment decisions. Risk-based asset pricing is also supported by project-specific tactics—such as technology prototying and hiring suitably skilled staff—aimed at mitigating or offsetting risk. As a final recourse, insurance tailored to the nature of the project is deployed (Pritchard, 2014). In this framing, the high WACC faced by SIDS reflect market assessments of its potential, and how market failure has occurred. Using this lens, low investment in SIDS is an unproblematic result of the operation of investment markets.

A second strand within the financial literature scrutinises how public policy influences investment decisions by reducing entrepreneurial risk and the cost of capital. It is the duty of relevant competent government authorities, using their mandates, to implement reforms to legal frameworks, policy and planning frameworks, political commitment, and measures directed at managing corruption (Benavides-Franco et al., 2023; Fleta-Asín & Muñoz, 2021). Public authorities carry the responsibility of creating an attractive space for investors, who, in turn, are ‘price makers’ in a hyper-competitive market of governments seeking capital for financing economic development. This is the case for institutions and regulations both specific to the project and more generalised to the ‘business environment’ within which the project takes place (Mignon & Bergek, 2016; Polzin, 2017; Polzin et al., 2019).

The literature on foreign direct investment (FDI) in SIDS underscores the pivotal role of governance in shaping their attractiveness to private investors. Frequently referred to as the “governance puzzle,” this challenge is intricately linked to issues such as corruption, political instability, and the delicate balance between maintaining national sovereignty and fostering investor-friendly environments (Forte & Neves, 2023; UNESCAP, 2019). Scholars have identified the need for targeted reforms in legal and policy frameworks, supported by public financing and international donor aid, as essential to reducing financial, regulatory, and market risks (Leal Filho et al., 2022; Ragosa & Warren, 2019). Specific sectors, such as renewable energy (RE), highlight these challenges, where domestic governance is central to overcoming barriers to investment (Dornan, 2015; Ragosa & Warren, 2019). However, despite significant efforts to enhance governance and create enabling conditions, private-sector investment in SIDS has continued to decline since 2017, exacerbated by the economic disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic (The Commonwealth, 2021). This stagnation underscores the need for innovative solutions that integrate governance reforms with sustainable development priorities to break the cycle of limited private-sector engagement.

Using the case of RE, two recent studies have made important contributions to understanding this problem for Commonwealth SIDS. Work by Ameli et al. (2021) shows that the relatively higher weighted average cost of capital (WACC) for RE in developing countries creates an ‘investment trap’ where “[h]igh-risk perceptions [reflected in high WACC] produce high premiums, increasing the cost of capital for low-carbon investments” (p. 2) and, therefore, significant lack of commercial or publicly-funded investment in RE. Exacerbating this self-reinforcing investment trap, Kling et al.'s (2021) study provides growing evidence that climate vulnerability in SIDS limits access to debt finance, further increasing funding costs.

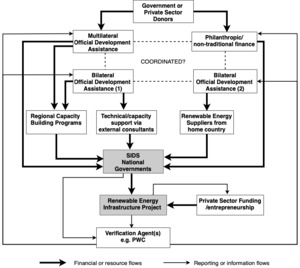

The standard advice around regulations and policy capacity building is insufficient for SIDS to overcome negative risk perceptions and, consequently, this ‘investment trap.’ To illustrate this with respect to RE, Figure 1 summarises the typical funding processes for funding RE projects in SIDS (Figure 1). Here, bilateral donor agency funding (e.g. development agencies) dominates, with the donor identifying, vetting, and managing projects, engaging with (expensive) external verification agents to certify and report on impacts. Donors (Figure 1) provide funds (thick lines) to development banks and/or philanthropic funds who, in turn, provide the funding to bilateral development assistance or regional programmes and then onto the SIDS national governments who are responsible for implementation. Funding is often channelled through technical consultants and suppliers drawn from the donor country, ensuring that a proportion of funds stays within the donor economy (Betzold, 2016; Dornan & Shah, 2016; Samuwai & Hills, 2018). Information provision (thin line) flows from the recipient country and the designated project to the verification agent and then back to the donor agency. Additionally, multilateral development agencies fund either regional capacity-building programmes, for example, the Pacific or Caribbean Renewable Energy and Efficiency Centres (CREE, 2022; PCREE, 2020), or directly fund SIDS national governments, again drawing on (expensive) external consultants to design and implement projects (World Bank, 2018). Private sector finance usually plays only a small role (Betzold, 2016; Dornan & Shah, 2016; Samuwai & Hills, 2018.

To explore why this model in Figure 1 can perpetuate an ‘investment trap’ in Figure 2 we rework the high WACC/low investment cycle set out in Ameli et al. (2021) and combine it with key elements from Figure 1. Here, Ameli et al. (2021) argues that the high cost of capital flows through to low investment in SIDS, which exacerbates a lack of economic development, high unemployment, high domestic risks and underdeveloped finance markets (Figure 2, black text) (Ameli et al., 2021; Blechinger et al., 2016; IPCC, 2023). In turn, this underinvestment contributes to worsening climate impacts, social instability, poor business environments, a poor pipeline of investable projects and, consequently, reinforces the high cost of capital. Ameli et al. (2021) uses a systems framing to argue that this self-reinforcing mechanism could be overcome with reform of sustainable finance frameworks to encourage international finance to invest in developing countries and development of local green bonds markets.

This contrasts with the FDI literature reflected in figure 1, which proposes that SIDS require donor funded technical support for capacity building in order to improve domestic governance and consequently address the ‘poor pipeline of investable project’. In Figure 2 we replicate this capacity building pathway from Figure 1 in the red text.

Both perspectives have a common focus on an institutional (relational, rules based) analysis and policy response to the investment trap. We agree with the implication that the core drivers of the high WACC are themselves institutional in origin but argue that Ameli et al. (2021) and the FDI’s literature approach cannot adequately explain the persistence of the investment trap.

Adopting an institutional perspective, we propose that the linkages between adaptive agents in a system contributing to a high WACC also influence persistent perceptions of risk. Using a systems framing, we identify additional factors that act as barriers throughout the investment cycle in SIDS. Drawing on insights from transition studies (Geels, 2020), systems dynamics (Sterman, 2000), and finance risk management (Pritchard, 2014), we argue these variables collectively explain the entrenched low-investment trap observed in SIDS economies.

We identify three broad types. First, structural risks associated with SIDS ‘islandness’ and political economic context, including extreme exposure to the impacts of climate change (IPCC, 2023), economic and population size, and therefore, project size, remoteness (Briguglio, 1995), high sovereign debt levels, and reliance on complex and variable processes for accessing donor finance (Figure 2, green text).

Second, following Geels (2020) and Geels and Schott (2007) we argue that governance aspects of socio-economic transitions associated with the execution of large-scale projects must also be explicitly considered (Figure 2, blue text). Three types of domestic governance challenges—political risk, risk associated with new operational routines and competing users, and social capital risk—that can influence the capacity of SIDS governments to deliver a conducive business/investment environment.

Third, while all investments and projects encounter project specific risks, SIDS face additional risks and barriers associated with limited data availability, and the relative underdevelopment of (some) Blue Economy technologies and industries for which SIDS have a natural endowment. Exacerbating these project and operational risks are the lack of investor networks and financial sector cultural biases (Ameli et al., 2021) that work against SIDS (Figure 2, orange text).

Individually, and collectively, these factors can act to push WACC higher (and returns lower) for investors relative to other global investment opportunities. To break this cycle, tailored innovations are needed to reduce investment risks for both investors and SIDS governments. Critically, these innovations for derisking need to be “tailored to the particular strengths and challenges in [SIDS]” (To et al., 2021, p. 1098).

Overcoming these barriers, therefore, requires an understanding of how these risks are generated and what institutional reform is required to actively manage them. These risks are explored in detail in the next section to craft a new understanding of the barriers to investment in SIDS.

3. Understanding Systems-Level Risks

To derisk the investment process, the previous section delineated three distinct dynamic risk profiles—structural risks, transitional risks, and operational risks—encountered by investors, governments, and other stakeholders within a SIDS investment cycle. These risks are interpreted as supplementary to the conventional political, economic, and financial risks typically anticipated by investors in larger jurisdictions (Baker & Filbeck, 2015).

3.1. Structural Risks

In the mainstream finance literature, structural risks are defined as any element operating in the market that could amplify the impact of adverse economic shocks (Hodula et al., 2023). The capital pricing model posits that investors should only be rewarded for bearing systemic or non-diversifiable risk that cannot be controlled or managed through active risk management strategies (Schwendiman & Pinches, 1975). Applying this same concept of non-diversification of risks to the context of SIDS, we identify four types of structural risks that could amplify project losses and deter investment for both investors and governments.

-

High public debt levels. SIDS are experiencing a high indebtedness, with debt levels increasing sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic (The Commonwealth, 2022). IMF data show that central government debt exceeds 72% of GDP across Commonwealth SIDS and small states with one-quarter having a debt/GDP ratio above 100% (2020 data, IMF, 2022). High debt levels are exacerbated by development assistance increasingly taking the form of concessionary loans to recipients rather than as grants, adding to the debt burden for SIDS. The relationship between public budgets and investment, particularly for infrastructure, means that high debt levels drive up project interest rates for investors and governments.

-

Exposure to climate change. SIDS have high exposure and high vulnerability to rising sea levels and storm frequency due to climate change (IPCC, 2021). Infrastructure investments in individual islands and energy projects can over-expose investors to irreducible climate-related weather events that damage projects (IPCC, 2023). The risks to physical infrastructure are likely to dynamically shift and increase over time as climate impacts grow more intense (IPCC, 2021). This will increase the costs associated with project insurance, depreciation, and rebuilding. This cost is largely unquantifiable, but, as an indicator, hurricane Maria’s impact on Dominica exceeded 225% of GDP (Wilkinson, 2023)

-

Small Size of Projects. Given the relatively small size of SIDS, this often, but not always, results in investable social or infrastructure projects that are too small to be of interest to private sector investors who seek to minimise relative transaction costs per unit of dispersed funds (Demirel et al., 2022; Treichel et al., 2024). This places SIDS in a poor competitive position relative to other projects seeking funds in a global market that can offer investors larger infrastructure opportunities that are more efficient to manage and operate (IRENA & OEE, 2023).

-

Funding application risks. SIDS governments, operating with limited skilled staff and resources, struggle to develop high-quality funding applications. The complex, varied, and time consuming process used by different funding agencies often necessitate engaging external consultants (Robinson & Dornan, 2017). This investment of time and resources represents significant opportunity costs and risks if projects fail to materialise (Afful-Koomson, 2015), potentially deterring SIDS from pursuing funding opportunities.

3.2. Transitional Risks

The structural risks discussed in Section 3.1 require resolution for both investors and SIDS governments to pursue investment in social or physical infrastructure. Although not commonly addressed in the literature, SIDS governments also face a specific set of socio-political risks associated with the transitions in economic, social, and political life that large-scale investment may bring to their communities and the administrative burden this will create.

Commonwealth SIDS have adopted ambitious targets to develop their Blue Economies—ocean-based activities like MRE, blue carbon, fishing, and shipping—as a strategy for economic diversification and resilience. These technologies and industries operate within complex socio-technical systems of institutions, governance, market structures, and cultural practices. Transitioning from existing systems, such as diesel-based energy to MRE, requires dismantling current socio-technical regimes and developing new ones better suited to Blue Economy economic activity (Kivimaa & Kern, 2016). While the literature extensively explores the politics and power dynamics in sustainability transitions (Köhler et al., 2019), specific risks for SIDS governments in these transitions remain underexplored. In this context, using examples from MRE investments, we identify three types of risks.

-

Competing user and social capital risks. MRE investments will require installation of new infrastructure in maritime or land zones that are likely already economically active, are important ecological sites or of significant cultural value to the community (Wright, 2015). In countries with (sometimes highly) limited land or near-shore resources, and in many cases strong traditional links to specific spaces, this raises the risk of conflict between competing user groups of spatial resources, and potential compensation for groups who lose access (Kerr et al., 2015). Aversion to conflict or preference for consensus is particularly strong in many SIDS (and Islands), where communal values and cooperative decision making is highly valued (Higgins & O’Tool, 2021). Such conflict could be disruptive to islander social identities, local affiliations, and psychological well-being (Lucas et al., 2017; Matheson et al., 2024). Siting projects in rich fishing grounds, transport routes, or areas of high biodiversity may also undermine the ability of SIDS governments to meet international treaty obligations. Additionally, incorporating participatory decision principles as part of project development to address these risks will necessitate the use of collaborative, community-based decision-making (McCauley & Heffron, 2018). This approach may lengthen and complicate decision-making processes, increasing transaction, and project costs.

-

Political Risk. While political risk is often discussed from an investor’s perspective, SIDS governments also face significant political risks in that they require local political support—and face political risk—to allocate scarce resources towards foreign-invested projects over other priorities. This support is crucial for navigating the transition phase, where established patterns of economic and social activity are disrupted (Lucas et al., 2017). For instance, the transition to MRE could lead to government-owned utilities losing market share, facing sunk costs, and workers losing employment opportunities and community legitimacy. Simultaneously, project proponents and foreign investors may gain wealth, influence, and control over vital energy assets, which may be contested and require SIDS governments to expend significant political resources to resolve (Köhler et al., 2019). The risk for SIDS is that such investments may create new social inequalities, undermining long-term economic development objectives and principles of economic justice. While these risks are also faced by other governments and sites of infrastructure investment, the small, often isolated, and high networked nature of SIDS communities make these risks particularly acute.

-

Investing in new operational routines to operate new infrastructure. Investing in new infrastructure—for example, a new MRE generating facility—will require SIDS electricity utilities to establish new daily operational practices and maintenance schedules, source new inputs and installation equipment, which are already in global short supply (Cartwright, 2022; Presley, 2022; Tang, 2022), develop new work practices and routines around scheduling, and develop new pricing structures. This introduces learning costs, transaction costs, adjustment periods, and ‘teething problems’ as new systems are developed over time (Köhler et al., 2019). These transition processes need to be managed against the need to maintain energy reliability (World Energy Council, 2019). This risk is exacerbated by the well-recognised difficulty SIDS face in accessing technical expertise either locally or through costly international consultants who operate on a ‘fly-in/fly-out’ basis (Dornan, 2015; Leal Filho et al., 2022; Weisser, 2004).

3.3. Operational and Project-Specific Risks

In any project, investors will always face resolution of a range of risks relating to the materiality of specific projects under consideration and their ongoing operation. These challenges are heightened when operating in the remote and small economies of SIDS, which is mainly recognised as a capacity issue (Lucas et al., 2017). We concur with these findings and extend them by highlighting three additional challenges of operating within SIDS that are less recognised.

-

Financial sector bias. Investors seeking to capitalise on project opportunities in SIDS face a unique set of challenges. First, SIDS often operate outside the established networks of the international finance sector, making it difficult for investors to uncover and nurture potential investment opportunities. Unlike other jurisdictions, there are limited avenues for building relationships and gaining insights into prospective projects within SIDS. Compounding this challenge is the need to overcome deeply ingrained cultural biases within the financial sector itself. The phenomenon of “home bias,” which refers to the tendency of investors to favour domestic investments over foreign opportunities, can act as a formidable barrier, further deterring investors from considering projects in SIDS.

-

Data availability for SIDS. Investment requires SIDS and investors to access robust, verifiable and transparent data that supports the identification of investment opportunities, specifically at the project level and on the overall quality of economic management and governance of the country (Habib et al., 2024). Data availability at the national level in SIDS is generally poor (UN, 2023). Data at appropriate scales to support MRE development in SIDS is inconsistently available in global or regional data sets and carry a high degree of uncertainty, risking a potential overestimation of usable electricity (Abba et al., 2022; Leal Filho et al., 2022; Lucas et al., 2017). Furthermore, data for resource assessments at finer scales, suitable for project-level evaluations, are fragmented and limited in availability (IPCC, 2021), raising risks around resource suitability.

-

Investment in pre-commercial technology. Current estimates identify wind and wave resources as promising for the Pacific and Caribbean regions (World Bank, 2021). However, ocean bed geomorphology limits fixed wind generation’s feasibility, favouring floating wind technology, a pre-commercial innovation yet to be tested in SIDS’ tropical conditions (IRENA, 2020). Similarly, blue carbon science lacks the robustness to support large-scale carbon trading, though efforts are addressing knowledge gaps (Macreadie et al., 2019, 2022). Tourism and fisheries, critical sectors, face escalating climate change risks (IPCC, 2021). These factors mean SIDS’ natural investment opportunities often involve higher risks compared to alternatives available to the global financial sector.

While the risks discussed in this section have been presented separately, in practice, these risks are interlinked and mutually reinforcing. Managing these risks will require governance innovation beyond the current prescriptions in the literature. We turn to examining governance innovation in the next section.

4. COMPASS: Governance Innovation for SIDS Finance

Existing frameworks for mitigating SIDS-specific risks predominantly emphasise enhancing domestic governance through institutional reforms, defined as the evolution of local institutions to address structural inefficiencies (Room, 2011). This approach is supported by technical assistance provided by regional agencies, the Commonwealth, and development banks (Asian Development Bank, 2021; Commonwealth Secretariat, 2021; Dornan, 2015). While such capacity-building efforts have yielded demonstrable benefits, they remain insufficient to address deeply entrenched systemic challenges, including climate change vulnerability, small market size, high levels of indebtedness, and persistent gaps in data, technology, and bias. These challenges lie beyond the control of individual governments and require multilateral, systemic solutions. Furthermore, current financial models that focus on single-jurisdiction project delivery and localised capacity building fail to account for the interconnected nature of these risks, which demand collective and innovative responses to effectively mitigate their impact on SIDS economies.

To analyse these risks, we consider four critical questions:

-

What are the potential or existing approaches to risk management?

-

Is the risk effectively managed within the existing risk governance models employed by investors and the financial sector?

-

If not, how can we articulate the governance or policy challenges facing SIDS in addressing these risks?

-

How can we draw upon the history of cooperation in SIDS and the theory of collective action (Ostrom, 1990) to create a new approach to governance that addresses these risks and barriers?

By systematically analysing each risk through these four questions, our goal is to pinpoint deficiencies in existing risk management frameworks, and, in response, identify innovative governance strategies to address these gaps.

This comparative analysis, summarised in Table 1, examines both public and corporate risk management strategies (columns 2 and 3) and their gaps in addressing the risks identified in Section 3. We then propose a collective governance model (columns 4 and 5) as a response to these various risk categories.

We draw several observations from Table 1. 1. First, most SIDS-specific risks are either not addressed or inadequately addressed by existing risk management approaches, particularly within the financial sector. Further, existing financial sector approaches are poorly adapted to SIDS (Dornan & Shah, 2016). This provides significant scope for innovation in how SIDS may learn from, use, and adapt risk management strategies to suit their specific circumstances.

Second, the cooperative concepts (Table 2, column 5) identified as potential responses to risk management challenges are not new ideas - either in the literature (e.g., Ostrom, 1990) or in practice for SIDS.

SIDS have a track record of collectively implementing economic and political institutions to manage specific risks (Table 2) in order to overcome the broader systemic risks discussed in Figure 2. Table 2 sets out a select range of examples in fisheries management, climate change, insurance and finance, but many others also exist.

Third, standard risk management tools (Table 1, column 3) implicitly assume a minimum efficient project size so that the costs of risk management and system transition are substantially outweighed by expected benefits. These minimum sizes are often larger than what is required by SIDS. Pooling resources to increase project scale or spread risks is a natural option to overcome this challenge.

To move beyond the single jurisdiction/capacity building model of SIDS finance, we argue that SIDS can leverage their historical experiences with collaborative risk management and established political relationships (Table 2) to create a robust organisation that institutionalises their track record of cooperation on mutual economic interests.

This approach aligns with broader international calls for reform of the global financial architecture. Building on insights from Table 1, we propose a new financial governance institution that would enable SIDS to work collaboratively with investors across sectors, financial instruments and countries, achieving necessary scale while actively derisking the investment cycle. The following section presents an operational model for this institution.

5. Introducing the Common Pool Asset Structuring Strategy (COMPASS)

In this section we present the Common Pool Asset Structuring Strategy (COMPASS), a new financial governance model as a new approach for SIDS to collaborate with investors. Developed in partnership with the Commonwealth Secretariat through the “Their Future, Our Action” project, COMPASS is designed to shift SIDS from making individual funding applications to collaboratively developing investable projects and opportunities which is subsequently presented as a portfolio to investors. Once finance is secured, projects are then implemented simultaneously across multiple countries under national regulations (Habib et al., 2024).

COMPASS enables SIDS to directly address seven key risks from Table 1: reducing transaction costs, increasing project size, facilitating equity finance access, managing data and technology risks, and mitigating climate and political risks.

COMPASS differs from conventional financing in three key ways. First, it emphasizes diverse funding sources beyond debt finance to incorporate a broad array of funding options. Second, it establishes a COMPASS Secretariat and inter-country coordinator to help identify common projects, access technical support, and facilitate private sector relationships. Third, it repositions SIDS to control project initiation, design, and resource flows, prioritizing their needs over investors’.

Using an example of MRE investment, an area of strategic importance to Commonwealth SIDS (Commonwealth, 2013), we envisage COMPASS working as follows.

5.1. Reducing Transactions Costs

The COMPASS secretariat provides technical and managerial support for national governments and entrepreneurs to identify and develop the business case for projects across different SIDS and in finding investors. Investors engage directly in open dialogue on project development and contracts with project proponents, who are coordinated and supported with technical advice via an agent within COMPASS and/or a project lead. Investors provide funds (thick lines, Figure 3b) for a project lead who distributes the funding to national governments for project implementation. This process improves the project value/transaction cost ratio closer to a level experienced by investors in other regions.

The investment relationship is facilitated between multiple SIDS, COMPASS and the investors through the use of accessible, transparent and robust data sets (thin lines, Figure 3b) made available via a dedicated software platform. This platform is co-designed to meet the information and data needs of SIDS, investors, and beneficiaries, taking into account, for example, the different data verification processes used by different types of investors and their rating agencies (Dimson et al., 2020).

The specialist software could be managed by a regional or multilateral agency or even a national government, acting as an administrator and facilitator, while participating SIDS retain and share their own data directly with investors. In this way, SIDS would engage with technology platforms to leverage their self-generated knowledge to facilitate institutional reform for their own benefit. This could have fundamental implications for changing the balance of power between SIDS and bilateral and multilateral donors (e.g., Soma et al., 2016).

5.2. Increasing Project Size and Accessing Equity Finance

To achieve the scale required to effectively reduce transaction costs, investment projects, such as a MRE project, would be developed collaboratively between SIDS who share common geographical, MRE resource, population, and energy demand characteristics, all characteristics that determine the size and type of MRE technologies suitable for use in specific locations. MRE investment projects and activities around specific technologies are initiated and rolled out simultaneously across multiple SIDS, allowing for pooling of resources, increasing scale, reducing transactions, and facilitating mutual learning and support. The bigger size of the projects will also facilitate access to equity markets as the collective project now meets private sector minimal sizes. Technical consultants and suppliers needed to deliver the MRE project are purchased directly by SIDS governments using a common contract to get value for money.

5.3. Addressing Data Gaps and Access to Technology

COMPASS would support SIDS to pool resources and collaborate on commissioning the appropriate data collection and research needed to advance, to a commercial stage, the MRE technologies that suit their biogeography. This approach would retain ownership and control of strategic data and, potentially, technology, and resources in the hands of SIDS governments. Where partnership with commercial players is required for IP and other technical reasons, collaborative approaches to market, through COMPASS, would significantly increase the bargaining power for SIDS. COMPASS could further support them through the provision of technical and legal advice.

5.4. Mitigate Climate Exposure and Political Risk

Countries participating in COMPASS to progress MRE investment would not necessarily be co-located in the same region. For example, the World Bank data identifies Mauritius, Fiji, and New Caledonia as having very high potential for offshore floating wind development, while some of their geographical neighbours do not (World Bank, 2021). Based on this common potential, these countries could collaborate with a third-party investor on a potential project around floating wind generation. In this way, COMPASS is broadly analogous to managing risk through an ‘insurance pool’ approach (Thoyts, 2010). Spreading projects across multiple geographical areas will also help investors manage risks around resource availability. The COMPASS approach will also diversify, and therefore lower the overall risk faced by investors across political and regulatory risks, a key part of attracting the non-debt finance needed by SIDS (Egli, 2020; McCauley & Heffron, 2018). COMPASS could, therefore, become a mechanism through which to pursue public-private partnerships, a management strategy often proposed as a response to debt risk (Madan, 2020), and address their limitations in developing country contexts (Leigland, 2018).

COMPASS’s primary purpose is to address structural risks associated with size and location. However, it may provide supplementary support for risk management in other important ways too. The focus of COMPASS on seeking investors interested in impact investing means that it is more likely for SIDS to find project partners that recognise the value of incorporating community, indigenous input, and ecological sustainability into project design. Further, the ability to negotiate with investors, as a group, provides a strong basis for SIDS to bargain for more favourable rights around any intellectual property associated with the technology and the project. Not all risk types are addressed by COMPASS. For example, risks around building political support must continue to be addressed by the relevant governments.

Collective action responses to common problems are not a novel approach. Many SIDS have strong traditions of collaboration either bilaterally or through regional organisations (CARICOM, 2023; Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2023; Commonwealth, 2022) to improve mutual economic outcomes. For example, the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (a tuna fisheries collective bargaining agreement) in the Pacific have been successful in increasing fisheries licence fees for Pacific SIDS by a factor of about 7 (Raghoo et al., 2018). Further, global collaborative approaches to provide a financial guarantee for RE investment in developing countries have also been proposed (Matthäus & Mehling, 2020). The COMPASS model proposed here seeks to expand and strengthen these collaborative efforts in order to provide a stronger mandate and supporting resources for seeking financial investments.

6. Conclusion

The need for institutional innovation to accelerate investments in SIDS, whether for climate change-related adaptation, mitigation or development purposes, is now a widely recognised narrative in academia and policy circles. Yet, few studies have developed conceptual models to show what this innovation might look like. Through creating a typology of SIDS-specific investment risks, this paper builds and presents a new approach to financial governance—the COMPASS model—to specifically address these risks using a framework that is demand-driven by SIDS, and is adaptable to localised needs, contexts and capabilities.

Our analysis makes two important contributions to the literature and, more broadly, to the ongoing political and policy debates around SIDs and finance.

First, we build on the earlier governance literature but adopt an explicit systems perspective in understanding risks and barriers to investment in SIDS. This broadens our understanding of the types of risks within the system and, therefore, the types of responses that can be developed. In particular, we argue that climate impact and market size associated with SIDS geophysical characteristics—their ‘islandness’—are key barriers to investors that governance reform cannot address, and therefore, a new approach is required.

Second, we argue that the key to overcoming these barriers is ‘scaling up’ the size of projects so that investable projects are designed to expand beyond the structural and resource specificity of the individual islands and take advantage of collective opportunities such as aggregate purchasing of technology licensing, the sharing of R&D risk or collaborative energy generation. By scaling up and reducing transaction costs and spreading risk SIDS place themselves in a strong position to attract funding support for investment in projects such as MRE.

Unlike exist mechanisms, such as the Green Climate Fund, the COMPASS model can be equally applied to other system-level investments where countries face similar opportunities but are constrained by systemic risks. Examples include onshore tourism development, biodiversity conservation, or skills training for youth. The key is recognising that SIDS and investors share common SIDS-specific risks and barriers, and by collaborating on strategic governance around risk management they can create new shared opportunities. The COMPASS model in this paper provides an example of how this could be done.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support and collaboration of the Centre for Resilience and Sustainable Development (CRSD) at the University of Cambridge, whose pioneering methodologies provided a critical foundation for this research. We extend our sincere thanks to our partners at the Commonwealth Secretariat for their strategic guidance and to the researchers, practitioners, and local communities who contributed to the COMPASS project’s innovative approach to resilience and sustainable development.

A special note of appreciation goes to the young leaders from Small Island Developing States (SIDS) who joined the research team virtually during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Their resilience, creativity, and commitment to building a more sustainable future have been a driving force behind this work, reminding us of the vital role that youth play in shaping the global response to complex challenges.

We also deeply appreciate the support of our funding partners the Commonwealth and Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) fund , without whom this work would not have been possible, and the broader academic community for their ongoing encouragement and critical feedback. Finally, we recognize the dedicated efforts of the CRSD research team for their commitment to advancing evidence-based solutions for complex global challenges.