Introduction

The Chiloé archipelago in southern Chile offers a unique case study of how island geography influences the impact of global and regional forces. Following the 1973 military coup that thrust Chile into the global networks of an emerging neoliberalism, new forms of industrial activity intensified in resource-rich areas like Chiloé. The archipelago’s inland sea was considered ideal for salmon aquaculture, which experienced a significant boom throughout the 1990s. As more of the population is pulled into wage labour and away from their agrarian and seafaring activities, researchers have documented the resulting socio-cultural changes. Before the salmon boom, Chiloé had some industrial activities, including a wood distillery that produced coal, alcohol, acetate, and tar from the native forests, as well as the timber extraction industry during the 20th century. However, most people relied on long-standing subsistence activities, which are believed to date back to the colonial encounter between Spanish settlers and indigenous inhabitants, that gave rise to the “Chilote” people (Daughters, 2019, p. 44). Nevertheless, following Pandolfi (2016), the discourse around a homogenous Chilote mestizo culture has been sustained at the risk of flattening other local identities. Although a majority of the population identifies as Chilote, experiences and identities vary widely across different areas of the archipelago. While the history of Chiloé has often been characterised as one of isolation and poverty (Barton & Román, 2016; Daughters, 2019; Grenier, 1984; Mansilla, 2009; Urbina Burgos, 1998), interrupted by the imposition of the neoliberal model, change and identity are not uniform and are closely tied to the islands’ geography.

Recently, challenges have intensified, particularly with the contentious project of the bridge over the Chacao Canal, which aims to connect Chiloé’s Isla Grande with the Chilean mainland. This project remains controversial (Cordero et al., 2023; Lazo Corvalán et al., 2021). More recently, virus outbreaks and toxic algae blooms (Bustos, 2014; Bustos & Román, 2019) have dramatically revealed the effects of industrial aquaculture on the local ecology. In response, the region’s complex identity is being rearticulated by protests and social movements. Bustos and Román (2019) examine Chiloé’s emerging political identity within the context of natural resource conflicts and ecological instability resulting from the imposed neoliberal framework. This was particularly evident after the 2016 ‘Mayo Chilote’, a widespread revolt triggered by severe algae blooms, which were reportedly caused by salmon waste runoff (see also Mondaca, 2017). The protests dramatically revealed that for the last three decades industrial infrastructures have become embedded in everyday life for many locals. The towns and small cities have grown rapidly, forming a new urbanity and an emerging Chilote modernity (Daughters, 2019). Several scholars, including Barton and Román (2016), acknowledge the unevenness of such processes, showing how they unfold alongside livelihoods that have defined Chiloé for centuries (Bacchiddu, 2017; Daughters, 2016).

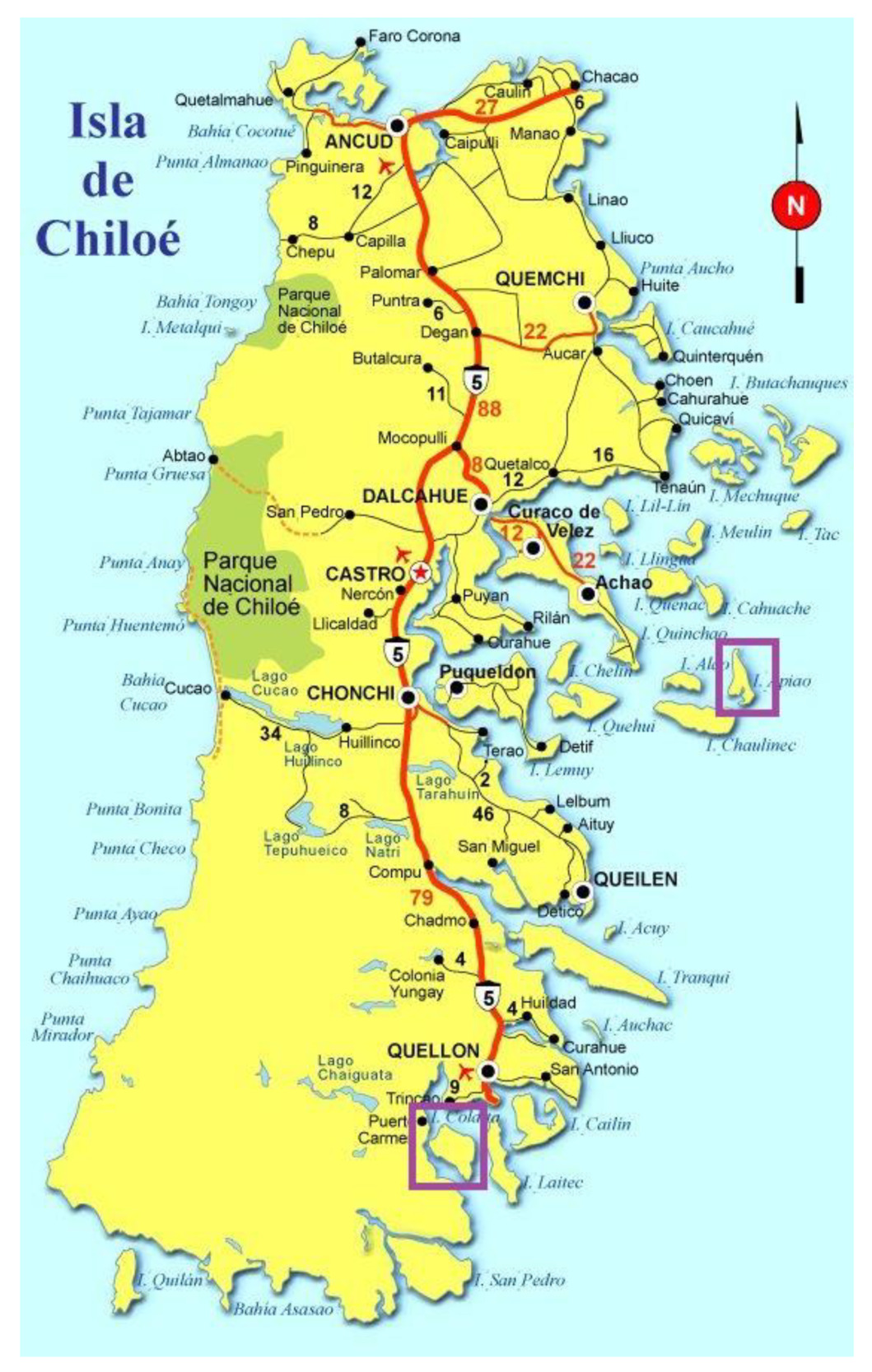

This paper draws on ethnographic research conducted over the course of a year (2018-2019) in various areas of Chiloé. However, each author has engaged in long-term anthropological studies in these areas—one with over 20 years of participant observation in Apiao and the other with 6 years in Coldita—where the transformations are particularly noticeable. We attempt an unprecedented approach to the analysis of Chiloé, ‘unpacking’ the archipelago and considering different ‘layers of isolation’ by comparing ethnographies from two different islands. These locations—one in the archipelago’s interior sea, far from Isla Grande, and the other in the indigenous southern area near a long-industrialized city—demonstrate the diverse ways people engage with both recent and longstanding processes of change. They also highlight how varying distances from urban centres impact different locations in distinct ways. This may offer new perspectives on Chiloé’s culture and history, as well as a deeper understanding of its engagement with modernity.

The first case examines Quinchao island and its town, Achao (population 3,500), which serves as a key hub for several outer islands. We focus on a group of islanders who received a government housing subsidy and relocated from the distant island Apiao (population 600) to Achao. Some of these individuals maintain connections to Apiao through government-subsidized transportation, effectively living in two places at the same time. This dual existence helps ease the transition from traditional livelihoods to urban life. The shift toward consumer modernity is counterbalanced by a process of “re-territorialization” (Richmond, 2018, pp. 1047–1048), which underscores enduring connections to traditional ways of life.

The second case examines the Huilliche community of Tweo Coldita on Coldita Island, located near Quellón, a rapidly industrializing city. The population of Quellón has surged from 34% urban dwellers in 1982 to 65% in 2017, with the current population at 27,000, two-thirds of whom reside in the city. Quellón serves as the main hub for migrants from nearby islands and other localities, offering opportunities in salmon and shellfish aquaculture, industrial fishing, education, retail jobs, and general wage labour. Most of these migrants are of indigenous descent, establishing city homes near their relatives while maintaining strong connections to their places of origin. Some individuals have residences both on the island and in the city. Colditans have been involved in extractive industries for over a century.

With these accounts we show how socioeconomic transformations that affect Chilote livelihoods might be considered from the concept of ‘layered isolation’. Building on recent work on the uneven and ambiguous emergence of contemporary Chiloé, we highlight the importance of both its island identity and archipelagic dynamics. When considering how the Chiloé province relates to the broader regional and global systems of power, it is easy to overlook what is happening on the smaller islands. If Chiloé is partly defined by the tensions of its isolation from continental Chile, there are various layers of isolation across Chiloé that are shaped by the archipelagic geography itself. If ‘islandness’ risks homogenizing difference, then an ‘archipelago-ness’ might help us maintain a critical and ethical openness to difference in its fragmentation (Cockayne et al., 2017; Vannini, 2011; Williams, 2012).

To explore these layers of isolation, we use ethnographic comparison as a key method for understanding the diverse experiences of islanders. We begin with a brief contextual overview of Chiloé and the transformative forces shaping it today. Next, we detail how Apiao islanders are embracing a profound transformation in their lifestyle while maintaining ties to their home. We then discuss how Colditans maintain their relationship with the city, highlighting both similarities and differences from their livelihoods, influenced by Colditan history and notions of personhood. Finally, we analyse what these perspectives reveal about Chilote engagement with modernity and tradition, and the various layers of isolation that can arise from any archipelagic geography.

Consumer Modernity and Mobility in Chiloé

The original indigenous inhabitants of Chiloé, the Chono and Huilliche, engaged in seafaring and small-scale agriculture, practices that shaped the Chilote population after the arrival of Spanish settlers in 1567. This new population, descended from both groups, blended culturally with the Spaniards while maintaining some distance (Saavedra Gómez, 2015). Today, distinct Chilote traditions are seen as threatened by the expansion of the salmon industry and other modernization processes, as many people move from the countryside to towns dominated by industrial activities (Alvarez & Hidalgo, 2018; Daughters, 2016, 2019). Chiloé’s geography complicates the spread of these transformative forces. The main island, Isla Grande, hosts urban centres like the provincial capital, Castro (population 34,000) and Quellón, while about 40 smaller islands lie in the inland sea facing the continent. This archipelagic geography, which shaped Chilote society, also made the region ideal for industrial aquaculture (Schurman, 2004), providing remote communities with opportunities for salaried work.

While the literature acknowledges the fragmented geography of Chiloé (Lazo Corvalán & Carvajal Hicks, 2018), it is often discussed as if it were inhabited by a homogenous population with the assumption that residents share similar lifestyles, goals, and concerns despite some notable exceptions (FSP, 2018; Lazo et al., 2020). Recent academic contributions on Chiloé in this journal have generally portrayed Chiloé as an island community (Barton & Román, 2016; Bustos & Román, 2019). While this is accurate, it downplays the fact that Chiloé is an archipelago of multiple islands, each experiencing distinct versions of contemporary social and economic realities, and varying degrees of access to commercial towns and the mainland. This is where the concept of layers of isolation becomes relevant.

An important aspect often overlooked in the literature is the significant indigenous presence within Chiloé’s population. According to the 2017 Census, 28% of residents in the Los Lagos region, which includes Chiloé, identify as indigenous. In the Quinchao and Quellón areas, the indigenous population makes up about 50% of the total. Although these statistics are based on self-identification and can therefore be variable and imprecise, ethnicity remains a crucial factor in the social landscape, as Chile’s indigenous population tends to be significantly poorer than the non-indigenous population (CORFO, 2019, pp. 6–7). Indigenous islanders seeking active participation in town life often face the triple stigma of being from a remote area, being peasants, and being indigenous (Bacchiddu, 2017).

Chiloé towns have grown rapidly in recent decades as industrial flows reshape the landscape and everyday life (Barton et al., 2013). Some authors have analysed the consequences of these processes on livelihood and identity. Lazo et al. (2020) note that some islanders are gradually exploring new possibilities, imagining leaving their marginal islands. Others noticed how Chilotes aim to participate in the urban social and economic sphere, often by accumulating cash through seaweed extraction (Morales, 2011; Morales & Calderón, 2010), expanding their “maps of desire” (Bacchiddu, 2017), and embracing modernity or experiencing new “imaginaries of modernity” (Morales, 2011, p. 185). Daughters (2019) described intergenerational conflicts faced by those reassessing Chilote tradition and modernity in today’s landscape.

Daughters (2016) and others have also documented the persistence of ‘traditional’ culture and livelihoods, especially in the smaller islands. There, the archipelagic geography becomes more limiting as some rural insular communities lack reliable and fast connectivity, while others enjoy it, or are closer to the city, like Colditans. Fishermen remain a powerful force in Chiloé. Bustos and Román (2019) detail their involvement in the recent unrest and protests against the government response to the latest environmental and economic collapse. The transformation of seafaring activities, along with activities like aquacultures, have been the main driver of change in Chiloé in recent decades.

An archipelagic approach to layered isolation may offer new perspectives beyond the tradition/modernity divide, highlighting local ways of engaging with these issues and potentially blurring that distinction (Saavedra Gómez, 2023). Evidence shows inventive strategies that merge traditional activities with wage labour. For instance, until two decades ago, Coldita Island had a salmon farm where locals worked while still tending their fields, gardens, and forests. Recently, shellfish farms have been established, and islanders now sell mussel seeds or participate in harvesting. In Apiao (Bacchiddu, 2017), consumer modernity has reached this rural community, with satellite dishes, mobile phones, and other consumer goods connecting them to broader consumer culture.

Layers of Isolation

Following Roberts and Stephens, we think of archipelagos as relational: a “temporally shifting and spatially splayed set of islands, island chains, and island-ocean-continent relations” (2017, p. 1). However, modern colonial thought has for centuries assumed fixity and dependency of islands to continents: archipelago islands have been treated as if they were all the same, as “interchangeable” (Roberts & Stephens, 2017, p. 29). The idea of “interchangeability” imposed onto the complex interactions within the Chiloé’s archipelago homogenizes islanders’ identity. But archipelagos are not constituted by a single kind of insularity. Rather, they emerge from a multiplicity of distances, of emergent “archipelagic relations” between islands, peoples, land, and sea (Stratford et al., 2011, p. 117). Moreover, as Baldacchino (2008) notes, longstanding portrayals of archipelagos as peripheral to modern continental life are entrenched in archipelagic relations. These representations have been challenging for islanders to overturn and, paradoxically, continue to shape their lives. Indeed, archipelagos are “culturally contingent” (Roberts & Stephens, 2017, p. 6), and thus dependent on history, on people’s experiences, and on the different ways they are represented. Roberts and Stephens propose that “thinking with and through” archipelagos means being attentive to the archipelago’s natural form, without missing its metaphoric dimension. This is because the concept of archipelago mediates “human’s cultural relation to the solid and liquid materiality of geography” (2017, p. 7).

Like other archipelagos affected by the epistemic violence of colonial modernity (Roberts & Stephens, 2017, p. 17), Chiloé and its islands have often been viewed as isolated, perceived as either distant from the ‘modern’, unchanged, resistant to change, or irrevocably altered. Catepillan (2020) has described how, in the 19th century, an “imagined landscape” (p. 120) that equated Chile’s identity and geography to its central valley began representing Chiloé as “insular” and “exotic”; a distant, poor, inhospitable and homogenous archipelago. These metaphors have nested in its archipelagic relations, for example, through the tradition/modernity opposition. But isolation is not merely a metaphor; the various islands of Chiloé interact with more developed islands, especially Isla Grande, the mainland, and each other in often diverse and precarious ways. These relationships are influenced by geographical challenges, varying distances, and limited connectivity, which frequently hinder access to modern life. There is not a single “mode of isolation” within Chiloé but manifold (Roberts & Stephens, 2017, p. 15). In Chiloé, the metaphor of the archipelago as one of isolated ‘islandness’ and homogeneous tradition has been consistently deployed, downplaying islanders’ experience and levelling their diverging concrete realities in terms of both isolation and change, as if these were evenly spread throughout the archipelago.

The concept of layers of isolation recognizes that isolation is there both in metaphorical and material terms, but also relationally and therefore unevenly. In Chiloé, isolation is layered because islanders engage with marginalization in differing ways, according to their relative distance from those islands where modernity is being reproduced more effectively. We suggest that this engagement with modernity evinces islanders’ capacity for ‘invention’ (Wagner, 1981, 2019), and their creative strategies in dealing with these distances. This layering includes isolation from the continent as a determinant archipelagic relation.

Certainly, considering an archipelagic approach for Chiloé’s diverse ways of engaging with modernizing processes is not new. In its 2016 study, Fundación Superación Pobreza (FSP) argues that islands respond differently to recent socioeconomic processes. They describe “the diversity that these islands manifest between each other and the diverse interactions they establish with modernity, breaking the prejudice of homogeneity that describes them exogenally” [our translation] (2016, p. 15).

Barton and Román allude to the contradictory transformations taking place in “late modernity” (2016, p. 660). However, the resulting picture of Chiloé seems potentially restrained by neglecting local differences that, we believe, transcend the traditional/modern dichotomy. Although thinking of Chiloé as an island is perhaps unavoidable, we propose an emphasis on its archipelago-ness to grasp the significance and appreciate the impact of this rugged, fragmented geography on its various layers of isolation and its highly differential connectivity. We attempt to understand the forces reshaping Chiloé at various levels of intensity, embodying dynamics of difference in different localities, and how these processes affect them (Cockayne et al., 2017; Williams, 2012). The archipelagic geography complicates the smooth dispersal of such forces. The tendency to assert a uniform, singular Chilote identity risks missing out on the variations existing across space, silencing those several pockets of mobility (Lazo Corvalán et al., 2020) that mark these different layers of metaphorical and material isolation. Considering an archipelagic geography is essential for understanding how global and regional processes unfold unevenly across different areas.

Improvements in transport and accessibility have increasingly allowed Chilotes to reach larger towns like Castro and Quellón, which are attractive due to their modern amenities. However, the vast archipelago poses mobility challenges, particularly for those in remote areas. Achao, on Quinchao Island and accessible by ferry, serves as a key port for outlying islands. Its large supermarkets draw visitors who make monthly trips from Apiao, a journey of two hours (Bacchiddu, 2017; Lazo Corvalán & Carvajal Hicks, 2017). In contrast, Colditans commute weekly to Quellón, with a boat trip of 45 to 90 minutes. There, they find sporadic jobs (e.g., boat repair, firewood, and sea product sales) or more stable positions in aquaculture centres and schools. Despite working in town, Colditans frequently return home to cut firewood, collect mussels and algae, and attend to domestic animals. These regional contrasts reveal layers of isolation often overlooked in Chiloé literature.

In the following sections we illustrate the contradictory forces of different aspects of change and continuity through ethnographic data. First, we describe and interpret the changes in everyday life and concepts of home for a group of islanders who have recently relocated to Achao from the remote island of Apiao. Being able to maintain a strong connection with their home island, the processes of de- and re-territorialization acquire a new significance, leading to a novel expression of Chilote modernity. Then, we discuss the Huilliche community of Tweo Coldita, whose history is marked by a close relationship with the city. Unlike Apiao residents, Colditans have been keeping two houses (one in the island and one in the city) for decades.

A “Miracle”: The New Townhouse Owners

The following section considers the urbanization of 131 indigenous families, including some from Apiao, who were offered subsidized housing a few years ago. Those who wished to settle in Achao and fulfilled the necessary requirements (such as having a bank account with a minimum deposit), could apply for the housing benefit. The project faced several bureaucratic hurdles that delayed approval and implementation, making its success uncertain until the final stages.

Successful applicants obtained a small house in a high-density town settlement for 290,000 CLP and committed to living in it for five years without renting it out or selling it. The new homes are compact, lacking front or back gardens, and are in close proximity with their neighbours. They have no space nor permission to raise domestic animals. This contrasts dramatically with their island lifestyle, characterised by expansive rural properties which allow for practical use of the landscape, provide a distance between neighbours, and allow for the cultivation of gardens and storing firewood. Despite the changes, they express satisfaction with their new life, aided by improved local transportation, including more frequent passenger motorboats with powerful engines, partially funded by the state. This enables them to regularly travel between their new home and Apiao, where they maintain their fields and domestic activities. They effectively manage dual residences, blending their traditional lifestyle and resources with their new urban environment, thereby stretching their social and cultural practices while aligning more closely with middle-class lifestyle.

In the following ethnographic section we used pseudonyms; permission to reproduce the data has been obtained by all informants. Achao has always been the main urban reference for the islanders of the Quinchao municipality. They are used to travelling there regularly to run errands and do their shopping. Moreover, their adolescent children attend school there, since Apiao rural schools only offer education to younger children. They usually travel to town once or twice per month, returning home in the afternoon on the same boat that took them in the early morning, with a heavy load of groceries, bringing back to their island homes a little bit of the town. Only some lived in the town, usually renting someone else’s property.

“Who would have ever thought that this miracle would have happened? Who would have ever imagined this one or two years ago?” María says with radiant joy as we approach her new dwelling. She is now the proud owner of a small townhouse, part of a housing project that relocated her and several other indigenous islanders to Achao from their native islands. Lucía, another member of the housing project, wishes to show us her new place. She nervously checks her pockets looking for her keys, an entirely new experience for her and the others, used to the handmade wooden doorknob common in Apiao, where nobody locks household doors. In the town, keys are mandatory.

The need for keys to enter the townhouse, far from being simply anecdotal, introduces one crucial difference between island life and town life. In town, the door is used only when leaving, returning, or letting someone in. On the island, however, the door is in constant use because daily activities extend into the backyard, which is an essential part of the household. The backyard includes spaces like the fogón for preparing pig feed, the orchard and greenhouse for harvesting, and the storehouse for firewood and potatoes. It is also where domestic animals are fed, where washing is done, and where wood chopping and animal slaughtering take place. The door is crossed frequently and fastened typically with a simple handle or thread to pull, making movement in and out easy and continuous.

We plan to visit another Apiao neighbour who also benefitted from this project, but nobody seems to be home. Peeping through the window curtains, someone from our small party comments: “You turn around a bit and someone stole your TV set, the town is not at all like the island.” It becomes clear that life in the new townhouses presents new concerns for many, and in contrast to María’s enthusiasm, not all testimonies are positive; ambivalence seems pervasive among many Apiao islanders. They tend to describe the town as an expensive, exhausting place that is good to know and access, but also a demanding experience for whoever must be temporarily away from the island. People often comment on how hard, and tiring, it is to walk on the pavement or the cement, a common experience when in the town. Furthermore, the town has always been considered dangerous when compared to the island, where everybody knows each other, and what to expect from each other, as opposed to the town’s unpredictability.

Magda, another proud homeowner, commented: “Now we are not from Apiao anymore, now we belong to Achao!” This statement carries multiple layers of meaning. On the surface it suggests that she now identifies with the town as the place of ‘belonging’, leaving the island as part of the past. Beyond this, owning a house in town also officially shifts their place of residence, symbolizing a broader desire to embrace change. This change connects these indigenous islanders to a form of Chilote modernity that emphasizes the “right to consume” (Miller, 2018, p. 127), blending elements traditionally viewed as opposing, such as modernity and traditional island life.

It quickly became evident that Magda’s statement was an exaggeration, a misrepresentation, or at least, a half-truth, given what transpired in the rest of our conversation. During our visit, it became apparent how compact everything is in the new houses compared to their homes on Apiao. In Apiao, the household’s physical space is expansive, while in the townhouse, it is much more confined. Everything is smaller: the stove—which is central to social life—the kitchen, the bedrooms, and even the view from the window, which is limited to a glimpse of the street or the neighbour’s house. The contrast is striking. Sipping yerba mate in the tiny kitchen, they shared how they left everything untouched in their island homes, including the surrounding fields. “Nosotros dejamos todo vigente” (“we left everything in perfect working order”), they say, listing every aspect of their countryside property and homemade belongings: their firewood, the necessary resources for meal preparation (cultivated crops and greenhouse vegetables), and especially the main Chiloé agricultural product, their potato fields. “There’s everything there. We told the municipality people, we live off our produce, they have to understand that we must tend to our fields. We sowed recently, so we have to go back,” they explain. They list every item left at home, emphasizing the importance of their stove. It is an expensive appliance, used to cook and heat up the kitchen, where people mostly spend their time. When people move temporarily to a different location, they leave the stove behind and regularly go (or send someone) to light a fire in it to prevent its deterioration. A working stove implies a strong connection between people and household. It symbolises a guarantee of continuity. They also pointed out that they had to sell or slaughter their domestic animals (sheep, cows, pigs, and chickens) because they need to be attended to daily and no-one could do it. These changes in their everyday routine leaves these migrants with more free time to devote to other paid or unpaid activities.

In some cases, the new houses are seen as a temporary arrangement: “If we manage to put up with this for five years, we can return there.” Inquiring further into the logistics of their new life, it appears that in most cases a family member travels regularly to the island bringing back firewood, potatoes, vegetables, and shellfish or seaweed. One of the women admitted that her husband was still living in Apiao, attending to their pigs and chickens, as well as to the fields; she travelled regularly to join him, and always stayed for several days. Over winter, these women found some activities to engage with in the town (attending craft courses, taking responsibilities at their children’s school); in summer, it is essential that they return to Apiao to work on the shores, collect luga, a seaweed, for profit that will be saved for winter (Morales, 2011; Morales & Calderón, 2010). Mere home ownership does not equal being able to afford life in the town; the municipality facilitated the islanders’ urbanization but did not provide any incentive to support a permanent move. Each person faces the challenge of finding paid employment, which can be difficult without the social connections that often ease the job search. Additionally, many available jobs demand specific skills that not everyone possesses. One possible solution to this dilemma is to inhabit two places simultaneously.

Until recently, travelling from Apiao was not easy, nor cheap. Private transport connected the island to Achao twice a week, weather permitting; usually one person per household would travel monthly, buying groceries for the family and often for the neighbours and close relatives. In the last 10 years the municipality has been partially funding transport to and from the islands. It is now possible to travel several times per week paying a fraction of what used to be the ticket price. The local boats are faster and much more comfortable than they used to be, consequently, people travel often and circulate more.

The declaration of belonging to a place captures the complexity of moving from one location to another, leaving behind one household and establishing another in a distinct geographical and social landscape. Such transitions are multifaceted and create an ongoing sense of disconnection or rupture in the lives of the islanders. Don Francisco, who moved out of Apiao permanently several years ago, and sold his family’s land, laconically commented on his fellow islanders’ new lifestyle: “eso es vivir a medias” (“this is living half a life”). This local expression conveys the fragmented, divided experience of someone who cannot live fully, because they are painfully lacking something fundamental to be able to enjoy life. Don Francisco and his large family moved to another rural area of Chiloé; they argue that they are happy there and adamantly deny missing the island.

Having closely observed their daily practices and compared them with life in Apiao, one striking difference is the shift from self-sufficiency to dependence on cash for basic needs, where once a trip to the beach provided a meal, now a trip to the shop is required. Each family member must now seek employment and earn money consistently to sustain their new lifestyle away from the island. This transition underscores a larger issue beyond finances: it reflects the broader challenges of adapting to an urban life that demands different resources, skills, and connections, ultimately reshaping their sense of identity and belonging.

The Colditan Viviente

The Tweo Coldita indigenous community occupies two territories that face each other, one on the south of Coldita island and the other on the Isla Grande of Chiloé. They are separated by a narrow canal. The community consists of some 20 extended families occupying patches of clear land by the forest, or fields. Fields are dispersed across the territory, all with direct access to the sea. Most Colditans can trace some form of kinship with other fellow Colditans: “somos todos parientes,” “we are all kin,” they say. An indigenous community is an organization defined by Chilean Indigenous Law, grounded on social relations between the inhabitants of a certain territory. It is in this sense that Tweo Coldita is called a community, but not every inhabitant of its territory belongs to it. The 2017 census registered 69 people living in its three localities (Oratorio, La Mora, and Blanchard), but this figure excludes the floating population (around 20 people) commuting from Quellón to Coldita, staying in their houses sporadically.

Colditans have maintained a close relationship with Quellón for more than a century. This is a port city whose multidimensional poverty—encompassing access to healthcare, sanitation, education, nutrition, housing quality, and employment—affects 36% of households (INE, 2017). Many homes lack proper sewerage, while several salmon and mollusc processing factories operate close to residential zones, emitting noise, odours, and fumes. Large transport trucks from the aquaculture and fishing industries destroy the city’s asphalt and unpaved roads. Quelloninos moor their boats along unregulated shores. The poorer residents build their houses with unreliable material and no council supervision. People from nearby islands take precarious jobs or illegally board artisanal fishing boats to work on the high-seas and earn cash, which is often spent on groceries and alcohol.

Many Colditans have migrated to Quellón and built their houses precariously on unstable soil, lacking basic services. These houses, often made from zinc planks and hardboard, are situated near salmon processing factories and the shoreline. Some received housing subsidies, however, the majority use plots that were sold or lent by kin. Those who live in Coldita but travel regularly to Quellón stay with relatives and send their children to live with them when they enter high school. They rely on a strong network of acquaintances and kin to find jobs or places to stay. They say that everyone knows everyone in Quellón, because they all come from “las islas,” the islands. When building or improving their city homes, Colditans may bring materials from the island, recycling remnants of fogones (smokehouses), warehouses, and even demolished or fallen houses. They buy used stoves or bring spare ones. Unlike the Apiao case, these houses resemble those on the island: they usually have a relatively spacious kitchen where visitors are received, and a small garden with dogs and cats. Most houses have their front yards covered with shells, a common sight on the island. These are the remnants of shellfish-based meals; sometimes, the fragments are used for fertilizing their city gardens, just like in Coldita.

Like the Apiao case, Colditans have a double residence. They come and go from their island fields to their city homes, bringing firewood, shellfish, fish, potatoes, vegetables, seaweed, and meat. In the city, they buy food that is unavailable back home to supply their island houses. Some of those who left their fields unattended for some time would eventually return, clear them, and resume activities like sowing potatoes or tending to livestock. Nevertheless, despite recognizing that some people are still minding their fields, Colditans feel the territory is being abandoned.

Constant travel between Coldita, the surrounding islands, and Quellón go way back. During much of the 20th century, people travelled by paddled boats or sailboats to sell their products to factories, especially timber and shellfish. Motorboats became widely available around the 1990s. For more than three decades, Colditans have had access to faster travel: first, through a service offered by the Coldita salmon centre from the late 1980s until around 2000; then, with bigger motorboats partially funded by the state. Today, some Colditans own vessels with outboard motors or slower, inboard ones. Colditans have been living between the city and their island for many years.

The Colditan concept of “viviente,” literally “living person,” is useful in understanding the relationship between Colditans and Quellón. Proper vivientes are defined by their dwelling in a field between the forest and the canal, separated from others. Vivientes must keep the field clear through seasonal cleaning, removing roots with oxen, animal grazing, slash-and-burn, and potato sowing. The forest must be kept at bay for two good reasons: a practical one as its growth makes agriculture difficult and a cosmological one as it is full of dangerous entities. These are spirits, unnamed creatures, lost animals, and aires (wind currents). Aires cripple whoever roams the forest, sometimes because witches manipulate them.

Vivientes leave traces in the land: trees, marks of potato plots, flowers, paths. They must know how to work by keeping the forest at bay, building fences, sowing potatoes, tending to animals, keeping an orchard, cooking, cutting firewood and timber, building houses and warehouses. They must also know the tides, which can often be strong in Coldita. Twice daily the canal recedes so much that one can cross from one section of the territory to the other on foot. Timing and the strength of the tide must be known beforehand, as it is said to affect the cultivated land’s quality, the sap of trees (which determines its suitability as timber), or where to anchor a boat.

Vivientes must also know how to relate to neighbours and kin; keep a proper distance with others, know how to talk and listen, be respectful, and be willing to help those in need. Even though the island is depopulating, which has greatly affected communal work, Colditans still exchange products between them: molluscs, potato seeds, fish, meat, firewood, clothes, even boat engines. They also buy and sell from each other, and thus money coming from the city is kept circulating within the community. Differences in income between Colditans certainly arise, but accepting offers to work with neighbours and paying workers properly are fundamental to maintaining ongoing social relations (see also Bacchiddu, 2012).

Two centuries ago, Colditans’ ancestors migrated from northern Chiloé, looking for new places to live (Saavedra Gómez, 2023). They settled in Coldita, becoming vivientes there, clearing land, following the tides, relating to others. Around 1908, Quellón was growing near a large wood distillery (Destilatorio de Quellón), built by a timber company (Sahady et al., 2009). Colditans say that their ancestors cut timber for this distillery from the nearby mountains, sending them to Quellón in large ships (Saavedra Gómez, 2023, p. 109). By the end of the 1950s, a sawmill was constructed in Puerto Carmen, near the Tweo Coldita community. Colditans worked for this sawmill, learning how to operate machinery. Land around this sawmill is now rightfully reclaimed by the Tweo Coldita community as their own (Saavedra Gómez, 2023, p. 113).

Spurred by the neoliberal policies of the Chilean state, a salmon aquaculture centre was installed in the Coldita canal in 1987, employing locals until 2003. Today, Colditans work in the shellfish aquaculture industry. They collect, process and sell luga seaweed as well as trap-caught crabs in Quellón and work seasonally in artisanal fishing. Colditans connect the island and the city through their work. For more than a century, they have been engaging with numerous productive activities, companies, and institutions, always maintaining a tight relation to their island environment. Recent modernizing processes have intensified wage labour and migration, yet Colditans manage to inventively transform and adapt as they engage with urban modernity.

An ethnographic example of the relationship between Colditans and Quellón will shed light on this. One of the most striking similarities between island and city houses are the shell fragments on orchards and patios. Coldita is filled with shell mounds. Researchers (Álvarez & Aránguiz, 2009) and Colditans agree that they belonged to the Chono, a seafaring people that lived between the Reloncaví estuary and the Penas Gulf when the Spaniards arrived (Núñez, 2018). Colditans have a paradoxical memory of the Chono. According to those who claimed to have seen them, they resembled otters and sea lions, not humans, but they also asserted that Colditans might actually descend from them. Colditans’ oldest ancestors came to the island long ago, sailing like the Chono from one place to the other, and building provisory houses on the beaches (Saavedra Gómez, 2023). The concept of quelcún, common throughout Chiloé (Cárdenas, 2017), indicates this practice of making a refuge at the beach when sailing to faraway places. In Coldita, to clear a field covered by the forest one needs to settle on the coast and make a provisional home, a rancha, like making quelcún, and similar to how the Chono lived.

Some Colditans have built their island houses over Chono shell mounds. A man was given a forested piece of land next to the Coldita canal by close kin. According to him, the place contained a hidden cave, and long ago an old woman fed witchcraft-related entities there. As his family made a rancha and cleared the field, they were constantly surrounded by baudas and coos (birds connected to witches). When they completed the task, the birds flew away. The family built a house on a big shell mound where they found stone tools and bones, which they say belonged to the Chono. Spreading their own shells around the house for at least two decades, they have enlarged this mound. A relationship between the Chono, Coldita’s history and the power of witches is apparent here, as they co-exist in the same place.

Belonging to the past, the Chono are both related and unrelated to Colditans. These ties take the form of witchcraft. Coldita is imbued with the dangerous, ancient power of witches. Also, Colditans build ranchas and make quelcún just like the Chono did. Unlike them, however, they have settled and stayed in their fields. Nevertheless, they are divided between the city and the island, historically moving in-between. In a way, their relation to the Chono questions their autochthony, their belonging to a place, as witches would do (while clearing a place to live, the man and his family were menaced by witch-birds, by a long-gone entity and by Chono skeletons). Colditans are both from and foreign to this territory: both past and present migrations and the need for clearing new dwelling places are the viviente’s driving forces. Migrating to Quellón and back is not a novelty. Quellón is embedded in their own complicated history and in their own sense of relating to the territory.

The harsh life of Quellón is familiar to the viviente. Through the shell mounds, the cosmological complications of autochthony are transposed from the island to the city, from the Chono to Quellón. Colditans believe that witchcraft is abundant in the city. Distances between houses are too narrow, and people from many places have arrived in recent years, bringing their own kinds of witchcraft. Just like the shell mounds, witchcraft is present both in Coldita and Quellón. In living in two places at the same time, going back and forth from Quellón to the island as they have done for more than a century, Colditans have spread seashells throughout their urban patios, just like the Chono shell mounds they have been feeding in Coldita. They are reproducing an ambiguous relationship to the past, the present, and places of dwelling that is profoundly historical. Through the seashells, Colditan vivientes elicit the long-time connection between the island and the city, which makes the issue of belonging, and thus of tradition and modernity, diffuse.

Indeed, Coldita’s history of settlement and migration, of creating vivientes, cannot be severed from Quellón’s history of modernization. Traditional livelihoods are immersed in the coming and going between the rural and the urban, and thus in the very experience of weaving archipelagic relations. This experience includes both material distance and local concepts such as witchcraft, autochthony, and the memory of the Chono. In the Colditan imagination, the Chono’s nomadic nature resembles their past and present trajectories between Coldita and Quellón. This shows how the dichotomy between tradition and modernity might not accurately reflect their lived experience.

Comparisons

Questions remain as to why islanders leave Apiao and Coldita for a new life. There is an upheaval in adjusting to an urban setting where the appeal of paid employment and a more ‘modern’ lifestyle can be achieved. One way to think about this is that the shift to urban life often reflects a desire for greater connection and less isolation, as people seek opportunities and amenities that their island homes may lack. Town life seemingly solidifies an “imaginary of wellbeing” (Alvarez & Hidalgo, 2018, p. 135) or several “imaginaries of modernity” (Morales, 2011, p. 185). For some, moving out of the island is an empowering way of ‘moving forward’ and a chance to partake in what they perceive as modernity (Bacchiddu, 2017). Chilotes have been historically mobile and prone to regular and seasonal mobility, looking for opportunities to work (Saldívar Arellano, 2018, 2019), relying on their initiative, their profound knowledge of the landscape, and their multiple family connections.

How islanders perceive their integration into modernity and their understanding of what modernity entails is a key aspect of their experience. For some it means staying in their place of origin, where their roots are, in their productive family lands. On the other extreme are those who embraced a full change and moved out of the island, sold their properties there, letting go of an important part of their personal and familiar history. Others, like the new homeowners of Apiao, have placed themselves in the middle point of these two extremes. For Colditans, this has been a long-term strategy.

A recurring theme in the literature (Bustos & Román, 2019; Daughters, 2019; Miller, 2019) is the view that Chiloé’s tradition and modernity are fundamentally incompatible. In this context, ‘tradition’ encompasses Chiloé’s cultural identity traits, such as solidarity, community spirit, and attachment to traditional lifestyles, food, and values. Conversely, ‘modernity’ is associated with characteristics of neoliberal logic and development. Our research demonstrates the need to consider local realities when addressing the concepts of modernity and tradition, and how they are experienced. It also shows that this dichotomy may be artificial and does not accurately reflect islanders’ experience.

‘Tradition’ is often contrasted with neoliberal economic values, such as aggressive market participation for immediate gain, short-term thinking, and individualism. Few Chilotes fully embrace these values, as neoliberal investments generally benefit a minority and have been promoted by the Chilean government for decades, leading to widespread distrust and resentment towards the state. The state is considered neglectful; any prospect of betterment, economic benefit, and advance must be taken advantage of. Colditans have managed to do so for decades, engaging with novel productive activities, techniques, companies, and the city, especially through the double-residence strategy. In Apiao, a handful of families managed to secure a house in the town, adhering to the urbanization project.

The perceived fundamental incompatibility with modernity is part of how modern colonial thought represents islands and archipelagos’ ‘tradition’, an idea that becomes embedded in local experience. In Apiao an often-heard expression is "aquí somos los últimos" (“we are the last ones”), while Colditans voice preoccupations that their territory is being abandoned. But there are differences between these islands. In Apiao, the statement signals the realization of being consistently neglected and excluded from development projects. The islanders tend to believe, and incorporate the vision that others have of them, and this belief becomes ingrained. “Why would you come here, and why would you keep coming?” a genuinely perplexed local asked us once. “There’s nothing here, it’s all so rural and unpractical (…) why would anyone be interested in coming here?” From her point of view, the interesting bits of Chiloé lay elsewhere. Apiao was just a far-away, difficult-to-reach, rural and marginal place that offered nothing to urban, educated people.

Colditans experience this differently. Even though they resent the fact that work and educational needs have forced them to abandon the island, it is also true that they are closer to the city than Apiao inhabitants, both geographically and historically. The current process of migration, forced by intense modernization is familiar to them: they have migrated before, and migration is part of who they are. They have been building city houses for a long time, similar to those of the island. Money is not a novelty, but it is ingrained in social relations back home. The opposition between life on the island and life in the city is less explicit because they have engaged with it for a long time, and maintaining ties with Coldita seems easier. Some people return, or keep their animals in Coldita, or build new houses there. In the city, Colditans use plots that belonged to kin and build their houses near other islanders. Some own boats and travel back and forth with relative ease, transporting family and neighbours. They carried local, ‘traditional’ characteristics to the city, like small orchards, old stoves, shell mounds, and witchcraft. For Colditans, the opposition between tradition and modernity, although identified as such, is not absolute. Their ancestors worked for timber factories in the past. Companies have been part of their life since at least the early 1900s.

Both Apiao and Coldita islanders have embraced change, though in different ways over time. Understanding ‘layered isolation’ is crucial for addressing ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’ within Chiloé’s archipelagic geography. As Roberts and Stephens (2017) suggest, Apiao and Coldita are not interchangeable within the Chiloé archipelago; their inhabitants interact with both the material and metaphorical aspects of isolation in different ways, ‘layering’ their archipelagic connections to modernity accordingly.

Partaking in modernity can be attractive for many. Bustos and Román (2019) noted, “the modernization ideal still prevails among its inhabitants” (p. 110). At the same time, Barton and Román (2016) wonder whether modernity is good for Chiloé overall. Daughters (2019) and Morales (2011) consider how modernity attracts people from small islands like Llingua and Apiao to work in the salmon farms. This shift disrupts or weakens traditional family networks that previously supported extensive cultivation and reciprocal arrangements, thereby altering the local economy, cultural identity, and daily life. Some authors suggest that Chiloé joined modernity through industrialization, especially with the salmon industry, which has undermined traditional community values and various subsistence activities. This change has created a dependence on salaried jobs (Román, 2015). Others argue that industrialization brought “a contradictory and complex version of modernity” [our translation] (Bustos, 2015, p. 241), unravelling a perverse relation between Chiloé workers and salmon farms, that Bustos names Stockholm Syndrome, where the abused idolize their abusers (2015, p. 251). While the industrialization of Chiloé has had irreversible and even destructive effects, in our experience it has also facilitated the emergence of new forms of tradition and local modernity. This process involves the integration of indigenous practices with new urban logics and practices creating unique local adaptations (Ravindran, 2015).

Conclusions

For Apiao islanders, owning a house in the town implies a re-invention and transformation of family connections. Regular commuters who cross the inland sea to shop in Achao rely on town connections for various forms of support, such as storing purchases, providing information, mediating with state or school employees, acting as guardians for the schoolchildren, and, crucially, providing hospitality. This last is a fundamental point. Hospitality is a cornerstone of social life in Apiao as it shapes both the principle and practice of sociality (Bacchiddu, 2019). While some ties may weaken, others are strengthened; the ability to offer hospitality in town is immensely empowering. Living in the town is a novelty, and the opportunity to be hosts allows indigenous structures and practices to evolve, enabling islanders to take the lead and build a different, novel future for themselves. The crucial aspect of this phenomenon is that these islanders maintain both experiences: they do not choose. To the state and some envious locals, it may seem that they have made a clear choice, however, their decision reflects an embrace of both the old and the new. The system of reciprocal obligations is not severed, rather adapted to fit new circumstances, interweaving new ways of doing things alongside traditional obligations, drawing on familiar customs to navigate the unfamiliar.

The Coldita case also contrasts with accounts that underscore a break between tradition and modernity. With its long-term relationship with Quellón, extractive activities and modernization, Coldita’s case shows that local history and local concepts (viviente, for example) are essential when addressing the issue of Chiloé modernity and its relation to tradition. An archipelagic perspective and the concept of ‘layered isolation’ illustrates that the opposition between modernity and tradition is experienced differently throughout Chiloé; its meaning is sometimes reformulated, and the opposition itself is nuanced or blurred.

We would like to highlight the concept of ‘invention’, following Wagner (1981, 2019), as the capacity to produce new symbolic references within a conventional context. In this case, the dyad tradition/modernity (within an archipelago usually represented as homogenous) stands for those same symbolic conventions which are re-conventionalized in practice. In Apiao, vivir a medias, (‘living half a life’), may indicate precariousness and dependency on institutional assistance. But it is also a manifestation of inventiveness: to enjoy a benefit with positive consequences in the long term, with practical outcomes such as access to health, or being nearer one’s adolescent children attending town schools. Inhabiting two places at the same time is part of a complex of inventive strategies that downplays local knowledge and emphasizes local needs to take advantage of state assistance. However, it must be said that not all strategize in the same way or with the same outcome. The same event is interpreted as ‘living half a life’ or as ‘a miracle’. In Coldita inventive strategies have been deployed for a long time now. Colditans have integrated a plethora of practices, in the past and in the present, that have connected them to Quellón and to global markets. The concept of viviente has been re-invented along the way, to engage with modernizing processes, incorporating new references, activities and priorities. For instance, in the last decade there has been a general turn from agricultural and timber activities to activities at sea, and thus new ways to work and relate to modernity. With strategies such as resorting to consolidated urban kin networks, steadily going back and forth from the island, selling produce in the city, spreading shell fragments in the yards, and notions like witchcraft, they have managed to keep an unstable relationship with Quellón, which complies with their ideas on autochthony.

In this paper we have highlighted the ways two island communities inventively engage with modernity. The notion of layers of isolation shows how the archipelagic geography of Chiloé allows the emergence of different histories and strategies, illustrating how islanders deal with tradition and modernity in unique ways. Their inventiveness challenges the representations of the Chiloé archipelago as a homogeneous cluster of islandness and isolation. Indeed, these ethnographies illustrate Chiloé as deeply archipelagic. Layers emerge as these islanders inventively engage with the materiality and the metaphor of isolation, making sense of ongoing processes of change while inhabiting two places at the same time, blurring the sometimes-monolithic opposition between tradition and modernity.

The notion of layers of isolation extends beyond Chiloé and can be usefully applied to other archipelagic realities. It serves as a valuable tool for examining and understanding how interconnected land-and-sea clusters develop distinct and inventive responses to contemporary global issues, revealing the diversity within these unique geographical contexts.

Acknowledgments

Fieldwork in Apiao was part-funded by C.I.I.R. (ANID/FONDAP/15110006); fieldwork in Coldita was funded by ANID BECAS/DOCTORADO EN EL EXTRANJERO 72180097.

Our manuscript benefitted from the valuable comments of three anonymous reviewers. Jacob Miller was part of the conversation that led to this article and we thank him for that. Giovanna gratefully acknowledges her Apiao friends and acquaintances for the many conversations over mate along the years and the various life changes we endured in the meantime. José Joaquín would like to acknowledge the inhabitants of Coldita, especially those of the Tweo Coldita indigenous community, who kindly opened their homes to him. He also acknowledges the priests of the Quellón parish, Father Luis Mora and Father Luis Neun, for kindly providing accommodation at the parish’s house in the city when needed. He is also grateful to Raúl Espoz, without whose support the fieldwork wouldn’t have been possible.