Introduction

Island regions possess unique natural environments and rich cultural heritage, often attracting significant numbers of tourists annually. However, poor tourism management can lead to severe ecological degradation and social tensions, especially in fragile island settings. To address these risks, many island communities and governments are turning towards sustainable tourism models to support local development. This approach seeks to mitigate tourism’s negative impacts while realising its potential to raise ecological awareness and create employment opportunities (Grilli et al., 2021; Pan et al., 2018). Sustainable tourism is thus recognised as an integrated practice that considers both present and future consequences of tourism development for all stakeholders. Rather than viewing tourism in isolation, this perspective frames it as an activity that spans multiple sectors, industries, places, and social groups—each with their own complexities and interdependencies (Duedahl, 2021).

This multifaceted nature of tourism in island contexts is rooted in what scholars term “islandness,” the distinct spatial, social, and symbolic characteristics of islands (Foley et al., 2023). Islandness encompasses the physical separation of islands from larger landmasses, producing a sense of spatial boundedness and remoteness (Conkling, 2007; Parker, 2021). Meanwhile, oceans function as connective spaces, facilitating continuous flows of culture and resources that link islands with continents and other islands in a broader relational network (Pugh, 2018; Ronström, 2021). In this view, islands are not isolated but embedded within complex networks of historical traditions, ecological connections, migration, and global exchange. This embeddedness makes islands particularly responsive to global changes, such as climate change, volatile energy prices, shifting tourism markets, and geopolitical disruptions. In small island contexts, the effects of such changes are magnified by the limited capacity to buffer shocks, owing to restricted ecological resources, small economies, and constrained institutional support (Foley et al., 2023; Folke et al., 2010; Kelman et al., 2011). As many small islands transition from subsistence-based economies to tourism-centric models, their growing dependence on external markets, international visitors, and foreign investment increases their exposure to global instabilities and heightens vulnerability. These vulnerabilities are compounded by the compact and interconnected nature of island societies, where even minor policy changes or external shocks can have far-reaching consequences (Kelman et al., 2011).

These interdependencies of systems—ecological, social, and economic—render tourism development a “wicked problem,” difficult to define, prone to unintended outcomes, and which generates new instabilities (Rittel & Webber, 1973, p. 160). In such contexts, linear or siloed planning approaches are insufficient. Instead, tourism challenges demand integrative and collaborative responses that can work across knowledge domains and stakeholder groups rather than single-group-dominated approaches (Baggio et al., 2010; Liburd & Edwards, 2018). The collaborative approaches discussed in this study are framed through the lens of co-design, a Scandinavian participatory design methodology originating in design research and technology design (Ehn, 1993; Simonsen & Robertson, 2012). We use co-design in a broad sense to refer to a structured process through which diverse stakeholders, including both experts and non-experts, collaboratively explore, envision, and develop innovative and context-sensitive solutions (Sanders & Stappers, 2008). It rests on the foundational principle that everyone is capable of creativity, and thus, emphasises facilitating active co-creation rather than just consultation.

Co-design holds particular importance in island tourism development due to the complexity and entanglement of socio-ecological systems in island contexts. In this setting, co-design enables the meaningful integration of plural knowledge systems, such as ecological wisdom from local fishermen, experiential insights from residents, and institutional perspectives from planners. The co-design process includes key collaborative practices of sharing knowledge, collectively identifying concerns, building ownership, and enabling participatory decision-making (Akama & Prendiville, 2013; Clatworthy, 2011). By bringing these diverse perspectives into dialogue, co-design creates a platform for more inclusive, adaptive, and locally grounded development, which leads to more resilient and equitable tourism futures (d’Hont, 2020; Neilson & São Marcos, 2019).

In the context of island tourism development, the object of co-design is twofold. On the one hand, co-design aims at the creation of tangible solutions or novel development ideas that address specific challenges. On the other hand, and equally important, the object of co-design is the cultivation of a social process: building shared understanding, shaping collaborative processes, strengthening relationships, and redistributing power among diverse actors (Liburd et al., 2017; Simonsen & Robertson, 2012; Steen, 2013). These aims are closely aligned with concepts of “collaborative governance” (Emerson et al., 2012, p. 1) and “cross-sector collaboration” (Bryson et al., 2006, p. 44). As such, co-design is not only a technical intervention but a social process. It is a process of co-learning and co-imagination, where new meanings, values, and behaviours emerge through participation and collaboration (Emerson et al., 2012; Steen, 2013).

However, despite the recognised value of co-design, local residents often struggle to participate meaningfully in island development processes. This exclusion stems from structural conditions such as commercial dominance, hierarchical governance, and reliance on external expert narratives (Connell, 2018). Tourism development is frequently led by external actors, such as resort developers and tour operators, who prioritise profit, frequently commodifying natural resources at the expense of ecosystems and community livelihoods (Connell, 2018; Thompson et al., 2018). Multi-level governance arrangements, involving off-island authorities, also impose top-down conservation measures, like marine protected zones, that may clash with traditional practices and marginalise groups such as fishers (Connell, 2018). Dominant sustainability discourses often favour scientific objectivity over local knowledge, reinforcing epistemic hierarchies that diminish residents’ ability to influence decisions affecting their environments (Moran & Rau, 2016). As a result, community voices are frequently overshadowed by the influence of powerful institutions and individuals that control resources and decision-making (Bason, 2010). These exclusions result in development concepts or solutions that neglect the needs of marginalised groups, limiting their ability to benefit economically or socially from tourism-led development.

Building on the challenges outlined above, we investigate how co-design practices facilitate equitable and dialogical participation among stakeholders in island tourism development. It draws on a six-month co-design project on Mayu Island, a southern coastal island in China, with the purpose of developing locally grounded solutions to persistent tourism-related challenges. The design team engaged government officials, committee members, residents, business entities, and tourists in a co-design process aimed at surfacing and articulating locally grounded problems, perspectives, and narratives. The emergence and exchange of diverse perspectives led to the joint proposal and implementation of two solutions: one addressing managerial problems linked to trash brought by tourists on the island, and the other tackling social and regulatory tensions surrounding informal vendor spaces in public areas. The findings highlight the effectiveness of employed co-design tools in transforming stakeholder knowledge into actionable solutions, empowering marginalised groups, and enhancing the inclusivity of decision-making processes. Building on these insights, we propose an evolving co-design infrastructure as a practical framework for island tourism development. This infrastructure comprises three interconnected components of mapping, narrating, and deriving, collectively supporting stakeholders in navigating the dynamic challenges and opportunities of tourism. By fostering collaboration and accommodating a wide range of viewpoints, this approach empowers stakeholders to actively participate in decision-making processes, ensuring that frequently overlooked voices are heard and enabling the co-creation of more inclusive and sustainable solutions.

Diversity, Openness, and Infrastructure in Co-design

In this section, we review the literature related to the co-design practice in island tourism, with a particular focus on the role of stakeholder diversity in framing problems and generating innovative ideas for promoting sustainable tourism development. By examining key concepts such as stakeholder diversity, openness, and infrastructure in co-design, the review emphasises the importance of integrating diverse perspectives, fostering meaningful collaboration, and developing adaptive frameworks to enable long-term, inclusive solutions for sustainable development.

Stakeholder Diversity in Fostering Innovation

Island tourism represents a multifaceted landscape involving diverse stakeholders, including residents, public sectors, business entities, and tourists. Each group brings unique perspectives and knowledge to the co-design process, and their active participation is essential to addressing the socio-economic and ecological complexities of island development. However, the success of co-design hinges not merely on assembling these perspectives but also on effectively integrating them. Boschma’s (2005) theory of proximity provides a compelling lens for analysing this integration, emphasising the roles of two proximities: cognitive proximity, defined as shared knowledge bases and ways of thinking, and organisational proximity, understood as the structural capacity for collaboration.

Building on this framework, cognitive proximity plays a crucial role in bridging the gaps between residents and public sectors. Residents possess valuable knowledge derived from their lived experience with ecosystems, such as seasonal changes and biodiversity (Simonsen & Robertson, 2012). This localised knowledge not only enables the development of solutions tailored to specific contexts but also uncovers overlooked issues and inspires innovative approaches grounded in people’s lived realities (Akama & Prendiville, 2013). For instance, fishers’ insights into marine biodiversity can inform conservation plans that balance ecological preservation with community livelihoods (Neilson & São Marcos, 2019). Similarly, Clifford-Holmes et al. (2017) demonstrate how local knowledge of water systems—such as practical decision-making, everyday information use, and long-term familiarity with water demand patterns and the impacts of maintenance funding—can compensate for gaps in formal data on supply–demand dynamics. Their study highlights the complex interdependencies between municipal infrastructure development, service delivery cycles, and the ongoing maintenance of water resources, suggesting that these forms of local insight are crucial for navigating infrastructural uncertainty and planning more responsive service systems.

Extending beyond cognitive proximity, organisational proximity highlights the public sector’s critical role in providing resources and governance structures that support the broad participation and effective implementation of co-design projects. The public sector’s resource support, such as funding, venues, and operational costs, is important to ensure inclusive access to co-design activities and encourage consistent participation, particularly for marginalised communities (Bason, 2010; Pirinen, 2016). In addition to providing material support, the public sector can offer clear policy guidance for co-design projects, for example, outlining what kinds of outcomes align with broader development strategies or are more likely to receive continued support. Such guidance increases the chances that co-design solutions will be officially supported, compliant with regulations and administrative systems, and feasible to maintain in the long term. As Bødker and Zander (2015) argue, even promising solutions risk failure without adequate policy and resource support, underscoring the public sector’s critical role in transforming local knowledge into sustainable, actionable policies.

Shifting Toward Openness and Adaptability in Co-design

The complexity of island tourism arises not only from the diversity of stakeholders and overlapping interests, but also from the spatial, ecological, and relational characteristics of island contexts. These characteristics give rise to tightly coupled socio-ecological systems, in which even small changes can cascade across environmental, economic, and social domains (Baggio, 2008). Here, Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) theory can help better understand and respond to such dynamics of small changes triggering cascading effects (Preiser et al., 2018). CAS theory frames tourism development as an emergent phenomenon shaped by adaptive agents and feedback loops. It highlights features, such as nonlinearity, uncertainty, and emergent behaviours, where cause-and-effect relationships are fluid and interventions may trigger unintended consequences. In practice, these characteristics are evident in island tourism development, where stakeholder tensions and conflicting priorities frequently arise. For example, on the Azores Islands, marine conservation policies triggered social tensions when local fishers, who were excluded from the process, faced livelihood disruptions and declining trust in scientists (Neilson & São Marcos, 2019). Similarly, a luxury tourism project on Denarau Island in Fiji increased flood risks due to rapid infrastructure expansion and poor land-use planning (Bernard & Cook, 2015). These divergent interpretations complicate consensus-building and make problem definition itself unstable. Such ill-defined and evolving challenges underscore the need for design approaches, which are open, context-sensitive, and responsive, to ongoing change and uncertainty.

Addressing these challenges in the island tourism development context requires more than goal-driven optimisation; it demands a continuous orientation toward learning and adaptation. From this standpoint, co-design is not simply a participatory process, but an adaptive design practice that brings together diverse stakeholders in a shared effort to sense, negotiate, and iteratively reframe problems. This involves revisiting and adjusting one’s understanding of a problem as new insights emerge. Dorst and Cross (2001) expand on this idea through their framework of co-evolution, which conceptualises design as an ongoing interplay between problem understanding and solution development. Rather than separating problem definition from problem-solving, the two evolve in tandem, each informing and reshaping the other. This cyclical approach is particularly suited to contexts where challenges evolve with each intervention.

To further navigate the uncertainties of ill-defined problems, abduction reasoning provides a valuable tool for designers. Rooted in Peirce’s theory (2014) and expanded by Steen (2013), abduction enables designers to hypothesise potential solutions based on incomplete or ambiguous information. These hypotheses are iteratively tested and refined, allowing designers to flexibly adapt to shifting contexts and emerging insights. By generating plausible outcomes and exploring their implications, abductive reasoning complements the broader co-evolution process, helping designers uncover hidden opportunities and reinterpret challenges through continuous exploration. As highlighted by the co-design tourism experts Sproedt and Heape (2014), “instead of asking ‘how can we effectively achieve a more or less known goal?’, we should ask ‘how can we effectively explore, create, and give meaning to something new, and engage in the process of encouraging new things to emerge?’” (p. 2). This shift toward openness supports continuous adaptation, allowing stakeholders to adjust strategies and respond to emerging challenges in complex systems like tourism.

Infrastructure in Co-Design: Building Foundations for Collaboration

This subsection introduces an important concept of ‘infrastructure’ in co-design practice (Björgvinsson et al., 2012). In its traditional sense, infrastructure refers to foundational systems that support socio-economic activities, such as water pipelines, transportation networks, or energy grids. In the context of co-design, the term has been reinterpreted and extended. Originally developed in Star and Ruhleder’s seminal work (1994) on information infrastructure, the concept has since been extended by participatory design scholars to describe the socio-material conditions that support sustained collaboration (Björgvinsson et al., 2012; Karasti, 2014). In the co-design context, infrastructure refers to the background arrangements—social, spatial, institutional, and technological—that enable ongoing participation, knowledge sharing, implementation, and adaptation over time. The verb “infrastructuring” has emerged to capture the ongoing, processual work of building, maintaining, and adjusting these enabling conditions over time (Karasti, 2014, p. 141). From this lens, infrastructuring is not viewed as a one-time activity or limited to the project timeframe, but rather as dynamic, evolving processes that foster inclusive and long-term engagement. This more organic approach allows solution opportunities to emerge gradually, shaped through continuous interaction and evolving relationships among participants (Hillgren et al., 2011).

Building on the understanding of infrastructure as a dynamic and relational foundation for ongoing participation, two important perspectives help deepen our grasp of how infrastructure functions in co-design. Firstly, Björgvinsson et al. (2012) conceptualise infrastructure as “arenas” that gather heterogeneous participants, legitimate marginal actors, and sustain constellations of socio-material relations necessary for transformative design efforts (p. 143). Infrastructure in co-design can take many forms, including physical spaces, digital platforms to facilitate collaboration (Seravalli & Simeone, 2016), decision-making frameworks to coordinate actions across stakeholders throughout the process (Akama & Prendiville, 2013), and shared artefacts or reference point to bridge diverse perspectives and terminologies (Björgvinsson et al., 2012). In this sense, infrastructure is not simply a background system, but a key enabler to turn differences into constructive negotiation and a source of innovation. Second, as Le Dantec and DiSalvo (2013) argue, infrastructuring is different from designing solutions to known or clear-defined problems. Instead, it invites stakeholders to surface, articulate, and explore issues that are complex, emergent, or unclear. To infrastructure is to create conditions for people to give shape to what matters to them, make space for different interpretations, and enable ongoing responsiveness to changing contexts and concerns. By staying open and flexible, infrastructure helps design activities remain relevant in dynamic environments.

To support diverse stakeholders and adapt to changing needs, co-design infrastructure often features “incompleteness” and “redundancy” (Simeone, 2019, p. 361). Incompleteness introduces uncertainty, allowing for continuous adjustments and innovations even after a project is completed. This flexibility helps to accommodate differences and resolve conflicts among stakeholders while enabling refinement in response to evolving situations. Redundancy involves overlapping or additional components, offering stakeholders the ability to engage in ways that best suit their preferences. For instance, remote experts may favour digital platforms, whereas residents might benefit more from in-person workshops (Eisenberg, 2006). Together, these traits foster inclusivity by providing flexible modes of participation, accommodating diverse perspectives, and promoting collaboration and innovation. Importantly, these infrastructural qualities are not just about accommodating differences. They facilitate constructive dialogues by providing spaces for stakeholders to express concerns and negotiate differences.

Project Overview: Co-designing for Mayu Island

Case Background

This study is based on a co-design project conducted in 2022 on Mayu Island, a small 0.24-square-kilometer island located at the estuary of Shantou City in southeastern China. Mayu Island was historically a resting point for fishers and gradually developed into their permanent settlement, recorded as early as the late Qing Dynasty (around 1840). Today, it is home to around 800 residents. Local governance is carried out by the Mayu Residents’ Committee with six members, under the direct administration of the extra-local Shantou Municipal Government.

During the recent decade, due to a decline in fish stocks, the Shantou Municipal Government has sought to transform Mayu Island from a fishing-based economy into a tourism-oriented island through a series of policy directives and development incentives. As a result, external businesses began investing in tourism-related industries on the island, especially new restaurants and cafés. With greater financial and operational advantages, these enterprises have increasingly displaced local vendors and eateries. This has created visible tensions between traditional livelihoods and emerging economic forces. Meanwhile, as tourist numbers have grown, residents have faced increasing pressures in daily life, including excessive beach litter, congested parking, and disruptions to everyday community rhythms. The second author, an educator from Shantou University, a local institution that has actively collaborated with government bodies in recent years to support regional economic growth and sustainable island development, became aware of these issues. He approached the Shantou Municipal Government and the Mayu Residents’ Committee, offering design consultancy support. His proposal involved using design research methods to develop novel tourism development ideas aimed at addressing the challenges and enhancing island community participation. Consequently, a cohort of 27 designers was assembled including the second author and other four design professionals from the second author’s design company, and 22 third-year undergraduate design students from Shantou University where the second author taught.

Islandness as a Contextual Lens

The island is not only a geographic context, but also a distinctive socio-cultural and ecological unit (Foley et al., 2023). The attributes of Mayu Island are aligned with three key elements of islandness: kinship-based governance, complex relationships with outsiders, and cultural ethos of wellbeing and resourcing. The first attribute is kinship-based governance, a form of authority exercised by elite families, commonly observed in other island contexts (Robinson, 2018). Two leaders of the Mayu Residents’ Committee came from the same dominant local family, whose relatives owned the island’s biggest restaurant. Decision-making, as observed during meetings and learnt from interviews, routinely favoured outcomes beneficial to the family’s business interests. Crucially, this use of public resources for familial gain was considered a socially accepted norm, with little stigma attached to the wider community.

A second element of islandness concerns residents’ mixed attitudes towards outsiders. On the one hand, island’s close-knit kinship networks foster a strong sense of internal cultural homogeneity (Baldacchino, 2012), leading to scepticism or wariness toward external stakeholders. On the other hand, self-perceived as small in terms of agency or power, they often have high expectations for the positive change that external resources and expertise might deliver (Nunn, 2004). The same patterns were observed in Mayu island residents. Prior to the arrival of the design teams, Mayu Island had experienced an influx of outside commercial ventures-such as cafes and restaurants disconnected from local culture, which were met with resistance by residents. To bridge this divide, the teams spent a week engaging in local consumption as tourists, building mutually beneficial relationships and gradually earning trust and recognition.

A third defining aspect on Mayu Island is the local approach to development and resource management. The island’s ethos, encapsulated in the local saying “work when there’s money, sleep when there isn’t” reflects a deep-seated preference for leisure and balance over relentless commercialisation. The interviews with island participants revealed that any development or economic initiative perceived as threatening residents’ daily wellbeing—through excessive noise, litter, or exclusion from public spaces—was likely to encounter resistance. Equally central is the tradition of collective resource management. On Mayu Island, fishing boats are commonly owned and maintained by multiple families. This practice of shared stewardship extends to local businesses, where residents often recommend each other’s services, a perception of shared resources observed in other island contexts (Nakamura & Kanemasu, 2022).

Stakeholder Landscape and Proximity Challenges

Understanding Mayu Island’s geographic, cultural, and ecological context is only part of the picture. Equally important is recognising the stakeholder landscape that shaped how tourism development unfolded on the island. To unpack these dynamics, we draw on Boschma’s (2005) theory of proximity to examine three key stakeholder groups: the Shantou Municipal Government, the Mayu Island Residents’ Committee, and Mayu Island residents. While each group played distinct roles, significant gaps in cognitive and organisational proximity impeded coordinated action and strained trust throughout decision-making processes.

The government was primarily responsible for initiating projects and evaluating the impact. And the committee served as the intermediary link between the government and residents. They were responsible for project execution and management but had no power of decision-making. These structural asymmetries were compounded by cognitive distance. The government operated with macro-level data and targets, often disconnected from the everyday experiences of individual residents. The committee, inclined to align with the government’s emphasis on macro-level concerns, similarly failed to register more localised concerns, such as venders struggling to sustain their businesses or the operational challenges of providing services. Organisationally, the absence of inclusive and structured collaboration mechanisms further widened the gap. Residents, with comparatively limited resources and institutional access, had few opportunities to contribute meaningfully to planning processes. Their perspectives were often underrepresented or filtered through official channels. In return, many residents expressed persistent distrust toward both the government and the committee, perceiving their decisions as driven more by political agendas than by the lived realities and everyday needs of the community.

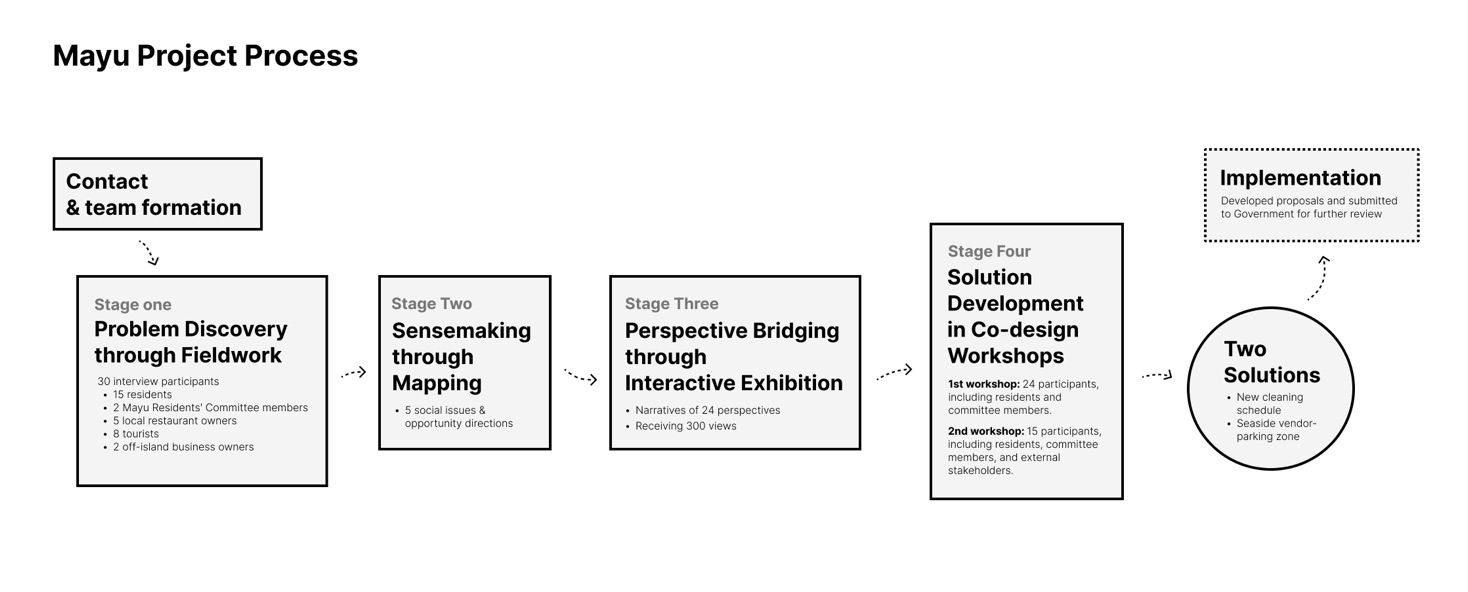

The Project Process of Four Stages

With this contextual and institutional groundwork established, we now turn to the co-design project process itself. The project began in October 2022 and spanned six months. It followed the four stages of 1) problem discovery through fieldwork, 2) sensemaking through mapping, 3) perspective bridging through interactive exhibition, and 4) solution development in co-design workshops (Figure 1). The cohort of 27 designers was divided into five teams that conducted the first stage of fieldwork independently, then came together for the second stage of mapping. For the subsequent stages, the second author and other four professional designers led the process. Below we will briefly introduce the four stages.

During stage one, the project began with fieldwork combining observation and in-depth interviews to discover problems. The five design teams each focused on a distinct stakeholder group of fishermen, residents, tourists, internal business owners, and external business entities, closely observing their daily routines and activities. Building on observations, they conducted 30 interviews in total, each lasting around 30 minutes. Interview participants included three government officials, ten fishermen, five restaurant owners, eight tourists, and two off-island business owners. Interview questions focused on everyday challenges, aspirations for the island’s future, and their views on tourism’s impacts and the roles and responsibilities of different stakeholders.

To synthesise and sense-make the results of the fieldwork, the five teams joined collaboratively mapped stakeholders and issues in stage two (Figure 2). In mapping stakeholders, the teams identified key stakeholders and visualised their relationships. This included both points of tension—for example, between those resisting tourism and those who supported it—and areas of collaboration, such as the joint promotion of local seafood to visitors. In another map, the teams discussed and clustered the issues emerging from the interviews, especially the challenges that were commonly experienced by or significantly impacted multiple groups. Also, within each issue, teams discussed underlying causes, specific events, involved stakeholders, and patterns of interdependency. This collective sense-making process identified five major issues: severe parking congestion, widespread beach litter, a lack of adequate public rest areas for residents and tourists, undesirable dining experience for visitors, and the underrepresentation of local cultural narratives in the tourism experience. The teams presented these findings in a midterm report to the Mayu Residents’ Committee and resident representatives.

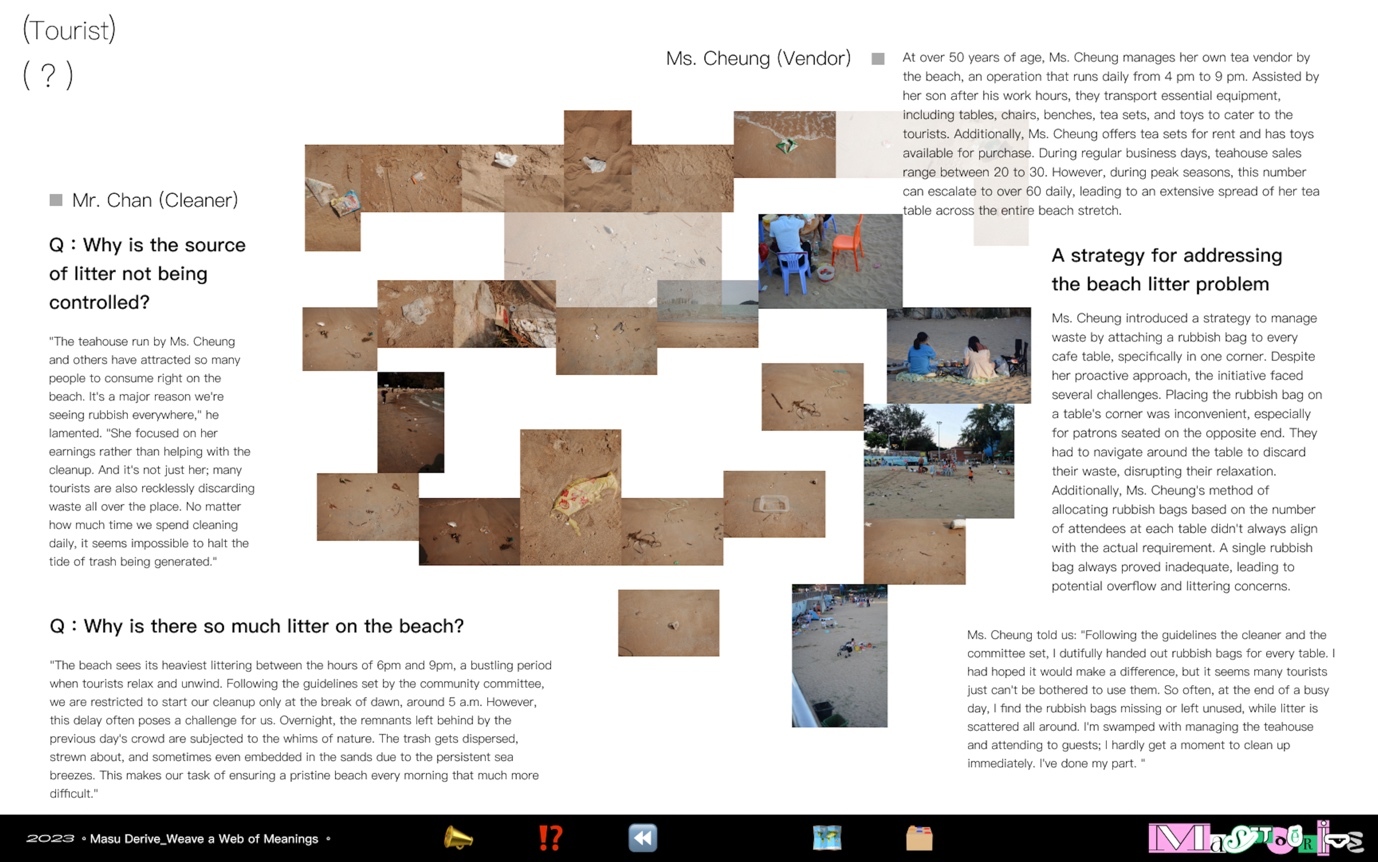

In stage three, following the midterm presentation, the student teams concluded their involvement, and the professional designers continued the work. To broaden participation in the exploration of issues and solutions, the team developed a digital exhibition titled “Masu Derive” on a webpage. “Masu” reflects the local pronunciation of Mayu Island, while “derive,” inspired by Guy Debord’s (1958) concept in psychogeography, describes a purposeful journey through an environment to discover hidden connections shaped by lived experience. The exhibition featured interactive narratives centred on the five issues identified in stage two. Each issue was presented through multiple perspectives of individual experiences and knowledge. These interactive narratives followed a non-linear, web-like structure, organised around 24 perspectives, comprising both human stakeholders (e.g., vendors, cleaners, residents, and tourists) and non-human elements (e.g., litter, fishing boats) (Figure 3).

The team distributed the webpage link to the “Masu Derive” exhibition through networks connected to government officials, committee members, residents, and external business stakeholders. In total, the webpage received about 300 views. Recipients were invited to explore the exhibition’s web of interconnected narratives, with particular encouragement to engage with perspectives beyond their own. By doing so, it was aimed at prompting them to consider new viewpoints and exchange insights on the same issue. For example, the viewer could start with the narrative of a fisherman who owned a boat, then follow links to see how his activities connected with residents, tourists, and other parts of island life. The exhibition’s interconnected narrative nodes allowed viewers to move seamlessly between detailed first-person narratives and explore each issue in depth from multiple perspectives, fostering a more comprehensive understanding of the intertwined nature of issues. These immersive and multi-perspective experiences gained from interacting with the “Masu Derive” exhibition laid the foundation for the co-design workshops in stage four.

At the last stage, two co-design workshops were organised, focusing on collaboratively developing solutions to the five issues identified earlier. The first workshop brought together 24 participants, including residents and the Mayu Residents’ Committee members. The second workshop included 15 participants, broadening the invite to external stakeholders who had engaged with the “Masu Derive” exhibition. In both workshops, participants formed small groups of five to six members, working collectively to discuss challenges, propose solutions, and reflect on the narratives presented in the exhibition. The “Masu Derive” exhibition remained central to the sessions, serving as both a reference point and a stimulus for dialogue, enabling participants to revisit diverse perspectives while envisioning actionable solutions. After thorough deliberation, each workshop collectively selected one proposal to carry forward. The proposals were evaluated by participants based on a combination of criteria, including feasibility, cost-effectiveness, alignment with community values, and potential for implementation within existing structures. In the first workshop, a cleaner proposed an adjusted cleaning schedule to address the issue of beach litter. In the second, a businessman suggested repurposing an underutilised coastal parking lot as a dedicated street vending space.

In the following section, we examine these two cases in detail, tracing how the co-design strategies enabled collaborative insights to emerge from stakeholders to address the two issues of beach litter and street vending.

Results: Addressing Beach Litter and Street Vendor Tensions

Next, we examine how the co-design process outlined above, especially the interactive exhibition “Masu Derive” at stage three, fostered collaboration in both understanding the issues arising from the tourism development and in formulating context-sensitive solutions. The exhibition served as a platform for synthesising and visualising complex relationships between perspectives and issues. By navigating interconnected narratives, stakeholders gained insight into how their own concerns related to those of others. This fostered a shared knowledge repository and helped reduce cognitive gaps. Also, the exhibition amplified the voices of those often excluded from traditional decision-making structures and provided valuable interpretations to forming collective understandings of issues. Here, we use the two issues of excessive beach litter and street vendor disputes to illustrate how the co-design process facilitated shared reflection and helped shape context-sensitive solutions.

The first issue of excessive beach litter had long plagued the island, exacerbated by the growing influx of tourists. During interviews, different stakeholder groups tended to blame to one another. Residents argued that tourists should be responsible for disposing of their own waste. Tourists, in turn, felt that food vendors should manage the waste generated by their stalls. Food vendors insisted they were already overwhelmed by the demands of service and lacked the capacity to monitor litter in public areas, suggesting instead that cleaners should bear the primary responsibility. Cleaners, however, expressed frustration over their excessive workload and called for additional staff support. Mayu Residents’ Committee members, citing budgetary constraints, did not see the need of extra hiring, instead attributed the litter issue to what they perceived as insufficient diligence and accountability on the part of the cleaning staff.

These fragmented narratives were interwoven into the “Masu Derive” exhibition (Figure 4), allowing viewers to explore the issue of litter from multiple perspectives of tourists, vendors, and cleaners. Notably, litter itself was also presented as one of the 24 perspectives. With these interconnected narratives, it became clear that how litter, like plastic bags and bamboo skewers, left on tables by tourists were not promptly cleared by vendors and were eventually blown by the gusty sea breeze onto different parts of the beach. Such multi-perspective experiences moved stakeholders from blaming to each other towards recognising shared responsibility. More interestingly, the links disclosed that gusty sea breeze, a previously overlooked factor, was actually a key contributor to litter dispersion. These insights were discussed in the co-design workshops. And at the first workshop, a cleaner proposed a solution that could effectively address this issue. She recommended adjusting the beach cleaning schedule to better coincide with periods of peak litter accumulation and prevailing breeze patterns. Previously, cleaning shifts ran from 5–8 a.m. and 1–4 p.m., but by then much of the litter had already been dispersed by the sea breeze. This new proposal shifted the schedule to 9 a.m.–12 p.m. and 5–8 p.m., aligning cleaning efforts with peak tourist activities and before sea breeze could scatter the trash. This minor adjustment was perceived to make cleaning more effective, reduce cleaners’ workload, and significantly improve overall beach maintenance.

The second issue of street vendor disputes reflected a complex dilemma among three stakeholder groups. Street vendors had long been part of Mayu Island’s local economy, and their numbers increased alongside the rise in tourism. Many operated in crowded public areas, which raised concerns from the Shantou Municipal Government about hygiene, traffic, and a deteriorating public image. In response, government officials issued public hygiene directives and instructed the Mayu Residents’ Committee to remove vendors from these spaces. However, the committee was aware of the vendors’ economic struggle, recognising that many were low-income residents who relied entirely on food vending to support their families. In an attempt to mediate between the government’s expectation and vendors’ livelihood needs, the committee had tried to explore alternative vending sites. Yet these efforts were unsuccessful, due to limited budgetary resources. As a result, the committee adopted an inconsistent approach, allowing vending at some times while prohibiting at others. This partial enforcement created the appearance of indecisiveness or incapacity, leading to dissatisfaction and complaints from both government officials and vendors.

The exhibition of vendors’ narratives highlighted their precarious economic circumstances, also revealed their roles in offering unique local food and service to tourists, which could potentially address another issue of lacking appealing dining experiences. These narratives helped government officials and committee members gain a more empathic understanding and appreciation of vendors, fostering a stronger motivation to seek solutions to support their business operations. Building on this shared sense of purpose, participants in the co-design workshops actively explored ways to support vendors. While interacting with the exhibition, a businessman noticed an underutilised coastal parking lot situated away from the main tourist thoroughfares. Despite the remote location, the site offered scenic views and a spacious layout. Thus, he proposed transforming this area into a proper seaside food market. This could not only provide more vendors with a dedicated, organised space, but also enhance the island’s cultural identity and enrich tourist experience. Its budget-friendly nature further strengthened the appeal of the proposal. Recognising its multiple benefits, the committee members promptly endorsed the idea. In the two months that followed, the committee developed a formal business plan for redeveloping the site, which was subsequently submitted to the government for further consideration.

A Co-design Infrastructure of Mapping, Narrating, and Deriving

Drawing on the co-design project presented above, we propose an infrastructuring process that includes the three components of mapping, narrating, and deriving. The three together constitute an infrastructure—an ongoing socio-material arrangement—that supports sustainable island tourism development. Mapping broadens stakeholders’ understanding of complexities. Narrating deepens empathy by connecting abstract issues to personal experiences. Deriving enables exploratory pathways toward future possibilities. Importantly, rather than being discrete steps or activities, these components function as an interconnected, enabling system that provides a flexible foundation for participation, sharing narratives, and adaption. Rather than prescribing a linear sequence, we encourage these components to co-exist and overlap at any stage of the design process. For instance, the three activities can take place simultaneously during one sense-making discussion or co-design workshop. This perspective shifts the focus from performing isolated tasks to fostering the ongoing conditions and capacities for collaborative knowledge-building and innovation. In the following sections, we introduce each activity in detail, highlighting how they contribute to building a co-design infrastructure within the context of island tourism development.

Mapping: Continuously Visualising Connections in Complexity

Mapping plays a critical role in organising and visualising interconnected elements within a complex system like island tourism. When stakeholders hold conflicting views or prioritise their individual interests, mapping offers a means to synthesise and structure these perspectives into an intelligible web of relationships. The process typically begins by identifying key nodes, like people, events, problems, and aspirations, and connecting them through lines of influence, causality, or interaction. In doing so, disparate elements are integrated into a coherent visual framework that reveals underlying patterns and dependencies. With this, the seemingly isolated issues are seen as part of a larger, interconnected system. This holistic perspective helps stakeholders anticipate how proposed interventions might ripple across the network, generating not only benefits but also potential unintended consequences for different groups. Moreover, mapping is not a one-time activity. It will evolve as new relationships and insights emerge. New nodes and lines are added as stakeholders deepen their understanding. Mapping’s openness allows it to be continuously adapted, ensuring that it remains relevant as the situation evolves.

Narrating: Transforming Abstractions into Concreteness

While mapping provides a broad view of interconnected relationships, stakeholders who have not directly experienced these relationships may find them abstract and difficult to grasp. This is where narrating comes in, allowing the abstract connections to be translated into human-centred concrete narratives. By sharing narratives rooted in personal experiences, they add a human dimension to the nodes and lines identified during mapping, helping stakeholders better understand the realities and nuances behind abstract relationships. For instance, in the issue of street vendor disputes, the vendor Ms. Cheung’s narrative revealed how her overwhelming workload of managing over 40 tables left her little time for a thorough cleanup. Encountering such a first-hand account would help to disrupt preconceived biases, discouraging stakeholders from hastily attributing the problem to vendor laziness or irresponsibility. Instead, the narrative fosters mutual understanding and empathy, opening space for more collaborative and context-sensitive problem-solving.

Deriving: Exploring New Perspectives and Possibilities

The third activity, deriving, encourages stakeholders to delve deeper into the content generated by mapping and narrating, much like a drift through narratives and perspectives, uncovering new angles and hidden opportunities. This deriving exploration can start with prompts, such as “Which perspective surprises you, and why?” or “If you followed a piece of litter, where would it take you?” These questions can be randomly selected by stakeholders or assigned to specific individuals to guide their exploration. For instance, in the co-design workshop, the government official was intentionally guided to start with fisher’s narratives, the perspective they had previously overlooked. In another case, a businessperson was wandering across the threads of parking and vending narratives, leading them to identify a previously neglected coastal parking lot as a promising site for a future street market. These explorations, much like wandering through a new city, foster the discovery of new relationships and ideas and integrate fresh insights back into mapping and narrating, ensuring a continuous cycle of growth and evolution.

Implications for Co-Design for Islandness

Having introduced the three defining attributes of Mayu Island: kinship-based governance, ambivalent relationships with outsiders, and a locally rooted ethos of wellbeing and shared resourcing, we now reflect on how these contextual dimensions shaped the co-design process. Further the discussion aims to offer implications for future co-design initiatives in similarly situated island contexts.

The first implication concerns the enduring influence of kinship-based governance. When decision-making is deeply intertwined with family networks, rather than attempting to challenge or bypass these structures, we suggest engaging with them pragmatically. Rather than confronting the blurred boundaries between public and private interests as a problem to solve, we suggest leveraging these kinship relationships to guide decision-making toward long-term, collective benefit for all island residents. This approach reframes kinship not as a barrier to equitable participation, but as a stabilising infrastructure through which collective outcomes can be anchored and sustained. For other small island contexts with similar governance ecologies, co-design efforts may benefit from accounting for how authority, trust, and accountability are embedded in social ties. Designing with kinship is not a compromise of neutrality, but a recalibration of what legitimacy and sustainability mean in place-bound co-design.

The second implication relates to the ambivalent relationship island residents often hold toward outsiders, which calls for a facilitator-oriented mindset for co-design processes. Their scepticism toward external actors coexists with a hopeful receptiveness to external knowledge and investment. This paradox results in trust that is both withheld and projected. Navigating this tension requires designers to adopt not a solution-provider role, but a facilitator mindset. A solution-driven approach focuses on delivering the most optimised solution crafted by experts. While well-intentioned, such an approach can result in outcomes that lack resonance with local communities and fail to integrate diverse stakeholder perspectives. It was evident in Mayu residents who had past negative experiences with outsider-led commercial ventures that were disconnected from local values. While the facilitator-oriented mindset reframes the designer’s role from experts to connectors, people who cultivate dialogue, enable participation, and foster mutual understanding and shared ownership of outcomes. This mindset was reflected in our design choice of building the interactive exhibition “Masu Derive.” By deliberately avoiding the delivery of the answer, or presenting summarised findings, the design team chose to stage multi-perspective and first-person narratives, unresolved and complex issues, to encourage mutual learning and collaboration. In such settings, co-design is legitimised not by problem-solving expertise as an expert, but by relational accountability as a facilitator. Thus, external designers or experts are neither heroes nor intruders, but facilitators.

The third implication concerns the island’s locally rooted ethos of wellbeing and collective resource cultures, which profoundly shape how development proposals are assessed and embraced by residents. Some island communities, such as Mayu, tend to hold a deep cultural preference for balance and leisure over relentless commercialisation, and they show low tolerance for the disruptions often brought by tourism development. This emphasis means that across all three activities of the co-design infrastructure, community wellbeing and everyday social cohesion must be treated not as peripheral concerns, but as central guiding values. Equally important, when island communities practise collective stewardship, like residents sharing fishing boats and mutually supporting business in Mayu Island, it challenges the dominant co-design assumption about the individual as the primary decision-making unit. Instead, island co-design should focus on relational economic actors-such as boat-sharing cooperatives, family-run stalls, and neighbourhood alliances-acknowledging that action and responsibility are often held collectively. It has broader implications to island tourism development, which is co-designing for shared rhythms, distributed responsibility, and culturally specific definitions of progress.

Conclusion

This article presents a case study of a co-design process that addressed persistent challenges in tourism development on Mayu Island. Rather than merely proposing ready-made solutions, the design teams focused on creating a set of socio-material arrangements—including mapping stakeholders and issues, exhibiting narratives from 24 perspectives, and co-design workshops—to encourage stakeholder participation and collaboration in understanding issues and proposing solutions. Through this process, we propose an open, dynamic co-design infrastructure, comprising three interconnected components of mapping, narrating, and deriving. Mapping expands understandings of complexities, narrating deepens empathy by connecting to personal experiences, and deriving opens up new avenues for imagining. These three are not isolated steps or linear activities, but rather integrated, evolving socio-material arrangements that shape and sustain the conditions for ongoing collaboration, shared meaning-making, and adaptive problem-solving. It is this capacity to continually hold open space for participation that marks this co-design process as an infrastructure rather than simply strategies or tools.

Consequently, the outcomes generated through the co-design process, both the solutions and the strengthened stakeholder relationships, support more grounded and enduring forms of island tourism development. By fostering collective ownership and bridging gaps in understanding and coordination, co-design builds local support, improves implementation feasibility, and enhances the capacity for long-term adaptation. These features contribute to more resilient outcomes that are better equipped to respond to the evolving needs and priorities of island communities and their partners.

Despite these promising outcomes, our study has several limitations. Foremost, given that infrastructure is an evolving process that should be deeply embedded within the island’s social fabric, our study lacked the long-term perspective necessary to fully understand and assess the sustainability and effectiveness of the resulting infrastructure over time. While our co-design process produced desirable immediate outcomes and a set of co-design activities, further attention should be devoted to examining how these activities could and would become integrated within local routines and practices after the withdrawal of the external design team. Future research would benefit from longitudinal studies that explore how stakeholders independently sustain, adapt, and evolve the co-design infrastructure, particularly in response to ongoing changes in ecological, social, and economic conditions. This would provide deeper insights into the long-term impact of infrastructuring practices and their potential as enduring catalysts for sustainable island tourism development.

_and_the_map_of_issues_(right).jpeg)

_and_the_map_of_issues_(right).jpeg)