1. INTRODUCTION

Island depopulation is an international challenge and is seen as an endemic problem in remote and peripheral areas (Chalmers & Danson, 2006), however, the severity of the impacts associated with population decline and how they manifest themselves vary across geographic contexts. Depopulation can directly affect community resilience by increasing community vulnerability, negatively impacting community confidence (Scottish Government, 2019), eroding local culture and indigenous language use (Atterton et al., 2022), and prompting changes to public infrastructure such as the closure of a school (Lehtonen, 2021). In a vicious cycle of decline, the reduction of services due to depopulation makes islands less attractive to both current and prospective residents (Atterton et al., 2022), potentially resulting in further depopulation and even the collapse of the community (Kim, 2021).

Depopulation of many of Scotland’s islands is a long-term trend. Census data indicate that the population of rural Scotland peaked in the early 1880s, but in the decades that followed, population decline was the trend for the majority of rural areas, most significantly in the north-west and far north of Scotland and the northern Scottish islands (Anderson & Roughley, 2018). During the early 1970s in Scotland (Anderson, 2016; Highlands and Islands Enterprise, 2015; Jones et al., 1986) and elsewhere, for example, in the United States of America (Lewis, 2000) and in France (Fielding, 1989), evidence for a rural population turnaround was reported. However, census data suggest that population growth was, and continues to be, spatially uneven: for example, in many national contexts, the populations of accessible rural areas have increased, while remote and very remote rural areas continue to experience population decline.

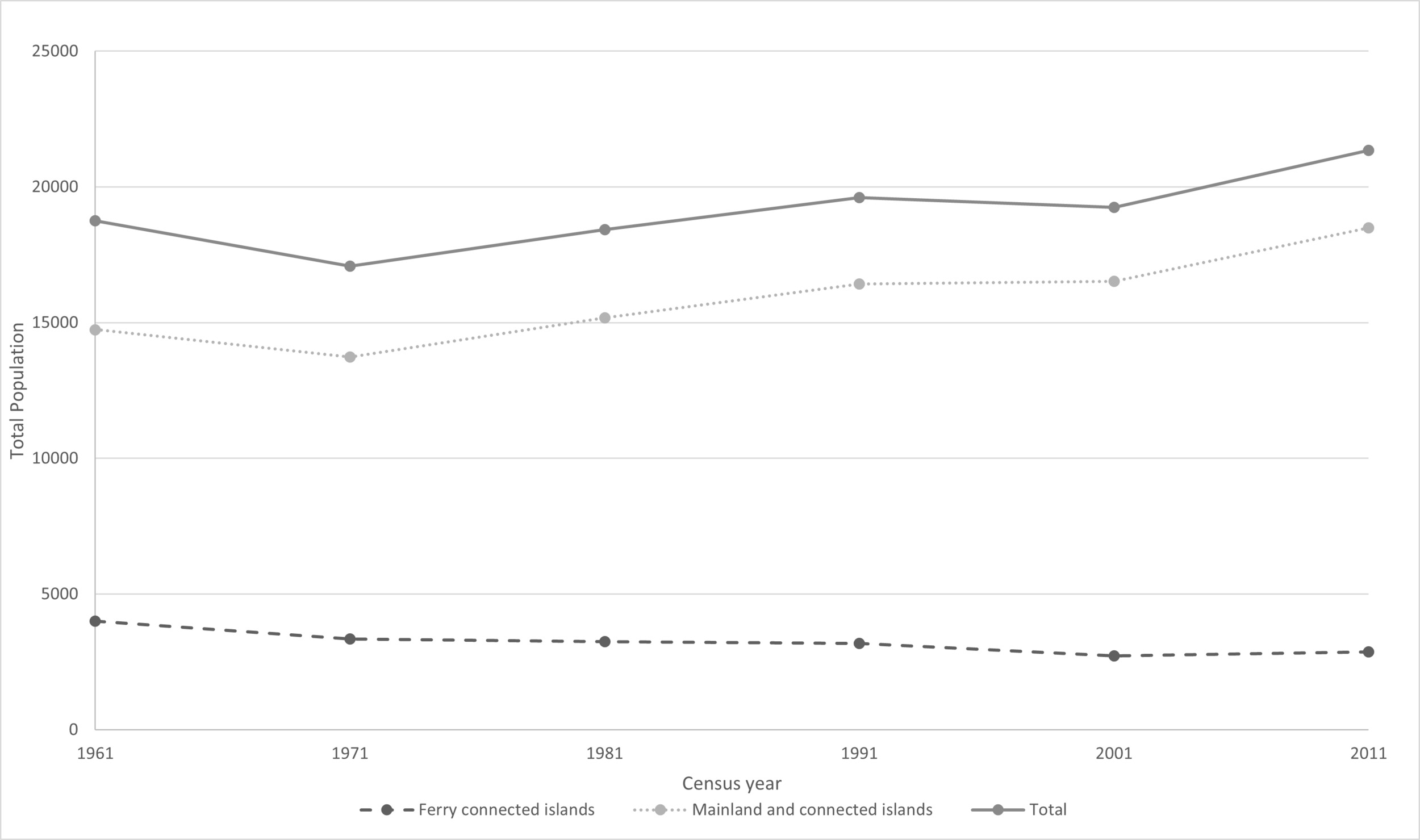

Recently, a succession of initiatives in Scotland has sought to address remote rural and island depopulation by focusing on increasing the resident population. However, census data suggest that any benefits of these initiatives have been geographically localised, and the depopulation trend continues in the more geographically peripheral communities. For example, census data report that, between 1961 and 2011, the population of the Orkney Islands Mainland and islands physically connected to the Mainland (by causeway) grew by 25.4%, whereas over the same time period, the islands not connected to Mainland Orkney lost 28.4% of their population (General Register Office for Scotland, 1973, 2003; National Records of Scotland, 2013).

The Islands (Scotland) Act 2018 legislated for the development of a National Islands Plan (The National Archives, 2018). The Islands Plan, published in 2019, comprises 13 objectives intended to improve outcomes for island communities. The first objective is: “To address population decline and ensure a healthy, balanced population profile” (Scottish Government, 2019, p. 3). In 2021, the Scottish Government published Scotland’s first national population strategy, and a further commitment to directly address island depopulation was made in the 2021 Programme for Government (Scottish Government, 2021a). Here, a financial incentive was proposed, the Islands Bond, a policy measure which aimed to stem depopulation in the Scottish islands by encouraging “young people and families to stay in or to move to islands currently threatened by depopulation” (Scottish Government, 2021b, p. 0). After a public and stakeholder consultation suggested a lack of support from islanders and questioned whether the bond could achieve its aims (Scottish Government, 2022a), the proposal was withdrawn in August 2022. Informed by a community resilience lens, this paper aims to understand what lessons can be learned from the Islands Bond proposal and other repopulation initiatives to inform any future policy developments that aim to grow the islands’ population in Scotland and elsewhere.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we present the conceptual framing for this paper, community resilience, by describing different interpretations of resilience and the relationships between resilience and population change. Second, we suggest the Scottish case is similar to experiences elsewhere by reviewing population trends over the last century, considering both patterns of rural population decline and the spatially uneven impacts of a counter-urbanisation-driven rural population revival. Selected measures taken to address rural depopulation are outlined. We then turn to the Scottish context, specifically Scotland’s inhabited islands, before introducing the Orkney Islands case study and the empirical research which informs this paper. In the context of community resilience, we then frame our findings around three themes: (a) factors identified as constraints associated with repopulation in Orkney linked with community resilience, adopting the stance that repopulation can lead to increased community resilience, (b) interviewees’ reflections about strengths and weaknesses of the proposed Islands Bond, and (c) lessons from the international context to support community resilience. Informed by attempts to introduce rural and island repopulation policies elsewhere, we offer reflections on why the Islands Bond was not adopted into Scottish policy. We conclude by suggesting six underlying Principles of Repopulation Initiatives for Community Resilience (PRICR) which should underpin any future policies concerned with island repopulation.

2. BACKGROUND

In this section, we provide an overview of rural population trends and present some examples of how formal initiatives designed to reverse rural depopulation have been employed in the recent past. We begin by considering the international context, focusing on trends within advanced economies, before turning to review rural and island population trends in Scotland, setting the context for recent formal commitments to address population decline in the Scottish islands.

2.1. Community Resilience

The concept of resilience originated in ecology in the 1960s. Holling (1973) defined resilience as the persistence of a system and its capacity to deal with change and disturbance. Similar to Holling’s interpretation, Thornes (2009, p. 125) refers to resilience as the response of a natural system to changes by “adopting a new equilibrium” (p. 125). At their cores, both definitions refer to the ability to ‘bounce back’ from a change in a system. Although links between ecological definitions of resilience can be drawn, differences in interpretation are influenced by scientific tradition and disciplinary and individual world views (Davoudi, 2012). The direct transferability of the ecological concept of resilience to social fields is challenging. MacKinnon and Derickson (2013) suggested that the ecological interpretation is “conservative” (p. 253). There has since been debate as to how community resilience from a social perspective should be interpreted: to date, there is no single definition of community resilience (Currie et al., 2024). Nevertheless, there are common elements which can be identified, including the ability to cope with stresses (see, for example, Adger, 2000), to bounce back from external shocks (Skerratt, 2013), and, crucially in the application of resilience in a social context, the ability for a system to sustain, adapt, and sometimes be transformational (Magis, 2010).

2.2. Community resilience and population change

The impact of population shrinkage and the ability of communities to be resilient are recognised in both academia and governments. Cáceres-Feria et al., (2021) refer to the loss of “demographic assets” (p. 108) leading to multiple consequences, which, in many areas, lead to high levels of community vulnerability; for example, the main threat to rural economies is a decline in human capital (Marini & Mooney, 2006). At the international level, the European Parliament refers to the loss of factors which may decrease community resilience, observing that “regions with a rapidly shrinking population are affected by a severe gap in the provision of social services (healthcare, cultural), physical (transport) and ICT connectivity, education and labour opportunities” (European Parliament, 2021, Online). At the national level, Scotland’s National Islands Plan states that depopulation is directly linked to increasing community vulnerability, stating “depopulation has an adverse effect on community confidence and service sustainability, increasing the vulnerability of communities already experiencing higher costs of service provision and market access” (Scottish Government, 2019, p. 18).

There has been a plethora of research considering efforts to promote rural community resilience in Scotland (Revell & Dinnie, 2018; Skerratt, 2013; Steiner & Markantoni, 2014). The focus of most of this research has been on improving understanding of how communities can be empowered to take action and respond to change rather than to wait for a response from external actors. Population dynamics have not been foregrounded in this corpus of research; thus, this paper offers a novel contribution to the application of social perspectives on resilience in the Scottish setting by considering how policy can enable more effective resilience during efforts to boost the population of island communities.

The narrative around population decline often focuses on the number of people leaving rather than considering who is leaving. Notable exceptions are the out-migration of young adults, commonly being described as problematic (G. A. Wilson et al., 2018) or the loss of a key individual, such as a doctor or a teacher, being identified as creating a challenge for a community (Farmer et al., 2003). Is the out-migration of young people, particularly school leavers who commonly move away to enter further or higher education, detrimental to community resilience? Dissuading young adults from moving away can potentially lead to “lock-in[s] and ‘backwardness’” (G. A. Wilson et al., 2018, p. 377). A better approach could be, as suggested by Stockdale (2004), to accept the desire of individuals to want to have new experiences and gain new skills elsewhere and to see their move as an opportunity for them to gain the “key ingredients” (p. 188) that could help rural communities. In order to support community resilience, therefore, a focus on young people remaining may not always be an appropriate aim of population change policy. Nor may a focus on the number of new residents be helpful. Attracting a small number of residents, regardless of age, who could plug local skills gaps, may be the best means of strengthening community resilience.

2.3. International population trends

Over the last century or so, across the Western World, rural places have experienced long-term depopulation (Stockdale et al., 2000). The resident population of many, most commonly small and geographically peripheral, rural areas has declined. In the years immediately after World War Two, sub-national demographic data show patterns of urbanisation for many nations (Serow, 1991). In most cases, this was a result of internal population redistribution, with people moving away from rural areas to urban centres and their suburban hinterlands. Out-migration from rural areas continues, and many rural communities have continued to witness net population loss often attributed to political and economic factors (Viñas, 2019). Drivers of in- and out-migration are, however, multifactorial and include, for example, (lack of) employment opportunities (Alexander, 2016), political change (Joseph, 2021; Parker, 2021), climate change (Kelman, 2021), (lack of) public transport (Czibere et al., 2021), (lack of) quality rural infrastructure (Despotovic et al., 2015), house price inflation (Canavan, 2011), and (lack of) economic opportunities (Mastilovic & Zoppi, 2021).

In most economically advanced countries, evidence for a reversal of long-term rural population decline was first identified in the 1970s and 1980s (Stockdale et al., 2000). Often driven by counter-urban population flows, some rural areas have experienced a population turnaround, termed by some as a “rural demographic renaissance” (Spencer, 1997, p. 75). Counter-urban population movement has been attributed to various and complex reasons, as observed by Halfacree (1994): “with a clear absence of any single explanatory process” (p. 164). Some prominent reasons for the move to rural cited in the literature include employment opportunities in sectors such as tourism (Halfacree, 1994), new industrial developments or the establishment of new businesses by entrepreneurial incomers (Bosworth & Glasgow, 2012), the rural idyll (Shucksmith, 2018), and phenomena such as the ‘race for space’, which is integral to increasing spatial inequalities (Kay & Wood, 2022).

The rural population turnaround has not been a universal process. Rather, rural population growth was, and continues to be, geographically uneven (Spencer, 1995; Tammaru et al., 2023). Scenically attractive places, coastal locations, and places with good transport links to large labour markets are often favoured by counter-urban migrants, whose move to such areas offsets ongoing out-migration (often of young adults). Conversely, other rural areas fail to attract new residents, and their population continues to decline (Tammaru et al., 2023).

2.4. Policy interventions

The continued depopulation of many rural and island areas has been identified in policy as a cause for concern, and policies and other interventions designed to address rural and island depopulation have been introduced in various national contexts. For example, in 1999, the Island Institute set up the Island Fellowship Programme in Maine, USA. It was designed to “help build sustainability within communities whose way of life and identity face many challenges” (Island Institute, 2022, Online). This programme places graduates with an associate, baccalaureate, or graduate degree into coastal and island communities for two years to work on specific projects, which have included working in a school managing a new greenhouse/agriculture project (Glass et al., 2020). Over the last 20 years, 129 Fellows have been placed, and 59 still live and work in Maine, of whom over half (34) live in coastal and remote communities (Glass et al., 2020). In Denmark, the settlement service, Bosætningsservice, helps potential migrants to move and settle in the rural, northern communities of Frederikshavn, Skagen, and Sæby (the Frederikshavn municipality) by helping them to find homes, education opportunities, jobs, and establish networks. Between 2006 and 2016, the population of the Frederikshavn municipality declined, but there was “a possible recovery in the first quarter of 2017” (Harbo, 2017). The number of salaried foreign citizens in the municipality, many from the EU, EØS, and EFTA, increased between 2010 and 2015 (Harbo, 2017). Japan’s national government have developed the Community Revitalisation Cooperation Fellows (CRCF) scheme under which the Local Authorities assign delegates who have migrated from metropolitan areas to work in a voluntary capacity in demographically disadvantaged areas. During their assignment, fellows work on tasks such as developing a brand for the area, in sales and public relations, in industries such as agriculture, forestry, and fishing, or carry out community collaboration activities (Oishi, 2019). As well as improving the livelihood of those living in the area, an aim of the initiative is that delegates will settle in the community they were assigned to work in. Over half (60%) of fellows have settled in the areas they were deployed to. However, a lack of clarity of the fellows’ responsibilities was identified as a weakness of the scheme, which has led to some fellows struggling to integrate into their assigned community (Oishi, 2019). In Italy, the 1€ Houses initiative operates across 60 municipalities located in rural and peripheral areas. Although the purpose of the project varies from municipality to municipality, a unifying attribute is offering the transfer of ownership of unused village homes for 1€. Attitudes of locals towards the initiatives, particularly in the areas where the scheme has been more recently introduced, have been positive (De Salvo & Pizzi, 2024). However, if success is measured based on the number of empty homes sold, there are notable differences across municipalities (De Salvo & Pizzi, 2024).

These examples illustrate the quite varied efforts employed to stem depopulation. However, the extent to which these have been successful is unclear, as criteria against which success may be measured and formal evaluations are rare. There is often little beyond anecdotal evidence of what makes a repopulation initiative successful or unsuccessful, pointing to a research gap. Where an attempt at evaluation has been made, there is a tendency to rely on evidence such as changes to local population profiles or an increase, no matter how small, in total population. This is rather simplistic, failing to account for any causal relationships between the initiative and any observed population change. In addition, these indicators cannot capture how ‘successful’ population change is actually experienced ‘on the ground’. For example, do those who move in response to a repopulation initiative stay for any length of time?

2.5. Population trends in rural Scotland

Scotland’s rural population peaked in the late 1800s. Throughout the 20th century, communities in rural Scotland, particularly in the Highlands and Islands, experienced large-scale depopulation (Wright, 2012). However, from the 1961–1971 intercensal period and through the 1970s and early 1980s, a time when the Scottish population as a whole was declining, signs of a rural population turnaround—albeit geographically selective—began to emerge. Growth was observed in some communities in the Highlands and Islands, and regional economic development policy stimulated industrial developments that attracted populations to centres of new manufacturing activity (e.g., the Corpach Paper Mill, which opened in 1965). The discovery of North Sea Oil acted as a catalyst for development in the 1970s and stimulated in-migration across North-East and Highland Mainland Scotland and the Northern and Western Scottish islands (Anderson, 2016). The Scottish Special Housing Association provided financial support for the development of new public housing to accommodate the growing population of places associated with the oil boom.

The Scottish rural population has grown in the 21st century, but this growth has been spatially uneven. Viewed through the lens of the Scottish Government’s 6-fold Urban Rural Classification, which distinguishes between ‘accessible rural’ and ‘remote rural’ areas based on the area’s population and travel time to settlements with a population of 10,000 or more (Scottish Government, 2022b), it is evident that remote and accessible rural areas have experienced rather different trajectories. For example, between 2011 and 2019, the number of people living in accessible rural areas of Scotland is estimated to have grown by 8%, whilst remote rural areas (a geographical category which includes Scotland’s inhabited islands) have experienced negligible growth, increasing by only 0.1%. Over the same period, the national population has grown by 3% (Scottish Government, 2021c).

2.6. The Scottish islands context

Scotland has more than 790 offshore islands (Atterton et al., 2022), of which 89 are inhabited (Scottish Government, 2024a). According to the most recent inhabited islands census publication (2011), island populations range from one person to over 21,000 (National Records of Scotland, 2015). In the recent past, there have been signs that the long-term island depopulation trend has been reversing. Between 2001 and 2020, it was estimated that the overall Scottish island population increased by 2.6% (a population increase of ca. 2,800 individuals) (Liddell & Aiton, 2022).

The longer-term picture from the most recent population projections, at the time of writing, published by National Records of Scotland (2020), suggests that population decline is likely to continue in all local authority areas with islands, ranging from 0.97% to 15.98% (Table 1) (National Records of Scotland, 2020). Nevertheless, it is important to note that Local Authority-wide population figures mask considerable variation at smaller geographical scales, a point alluded to in the Scottish Government’s Action Plan to Address Depopulation (Scottish Government, 2024b). In the exclusive island local authority areas (Table 1), population centralisation is being observed around Lerwick (Shetland), Stornoway (Western Isles), and Kirkwall (Orkney) (Hopkins & Copus, 2018). At the same time, smaller communities across these archipelagos continue to see population losses, a trend that was noted in the National Islands Plan: “Over the last 10 years, almost twice as many islands have lost populations as have gained” (Scottish Government, 2019, p. 18). As such, significant depopulation in smaller islands is being hidden by reporting population change at the local authority level (Scottish Government, 2024b).

2.7. Scottish island repopulation initiatives

In the recent past, some local authorities serving island communities have sought to address depopulation by encouraging inward migration through approaches designed to address issues such as relocation costs and the availability of residential property. For example, between 2016 and 2018, Argyll and Bute Council operated the Rural Resettlement Fund (RRF), a scheme which offered financial support ranging from £5,000 to £10,000 (Glass et al., 2020) for “economically active young people relocating, returning or staying in Argyll and Bute to take up employment; economically active young families relocating to Argyll and Bute to take up a job; and micro and SMEs relocating to Argyll and Bute” (Argyll and Bute Council, 2019, p. 4). The RRF supported the relocation of 193 people to Argyll and Bute, with 53 individuals moving to island communities in this local authority area. It was noted in the RRF applicants’ feedback that the financial support available to support a relocation was considered to be important to their decision to move. In June 2021, Community Development Lens (CoDeL) launched the Uist Beò initiative under their Smart Islands project. Launched online to celebrate “the unique culture and the thriving life of our islands, from Berneray to Eriskay!” (CoDeL, no date: Online), their website includes details on what it is like working and living in Uist, advertises job opportunities and has guidance on finding housing (Uist Beò, 2024). In a recent presentation to the Rural Social Enterprise Hub, it was suggested that the Uist Beò initiative is an example of how “digital technology can be used to tackle depopulation” (Rural Social Enterprise Network, 2024, p. 2). In the Orkney Islands, the Gateway Homes concept aimed to encourage families to make a long-term commitment to living on the islands and has helped to bring empty homes back into occupation (Orkney Islands Council, 2018). Through fixed-term tenancies of around 12–18 months, Gateway Homes allows potential residents to experience island life without committing to purchasing a house. The demand for Gateway Homes varied across the islands. However, even where demand was high, depopulation continued due to a lack of suitable properties for people to move into after their Gateway House tenancy ended (Glass et al., 2020). Provisions in the Private Housing (Tenancies) (Scotland) Act 2016 also emerged as a challenge. Tenants did not need to commit to a fixed-term tenancy and, as a consequence, could not be compelled to remain a tenant of a Gateway Homes property for the intended 12–18 months. Therefore, they may not have fully experienced island living (Glass et al., 2020).

These Scottish repopulation initiatives have had some success in increasing population numbers, at least in the short term. However, in the absence of detailed evaluations, their impact in the longer term is unclear. It is unknown if those who took up the incentives stayed in the medium term and whether the numbers who came—and stayed—exceeded the number of out-migrants and population lost due to natural change.

2.8. The Islands Bond

The Scottish Government’s Programme for Government, covering the period 2021–2022 (Scottish Government, 2021a), set out plans for an initiative to address island depopulation via an Islands Bond (Scottish Government, 2021b, p. 0). This initiative proposed to award up to 100 bonds of up to £50,000 to young people and families to “support people to buy, build or renovate homes, start businesses and otherwise make their lives for the long-term in island communities” (Scottish Government, 2021b, p. 0). Media reports following the publication of the proposal suggested that opinions about the bond varied, with some commentators seeing it as necessary support for those wishing to buy an island home, and others feeling that the money could be better spent elsewhere (BBC, 2021). In August 2022, following extensive community and other stakeholder consultation, the Islands Bond proposal was withdrawn (Scottish Government, 2022a).

3. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORKNEY ISLANDS

The Orkney Islands are an interesting example of population change and a suitable case study within which to investigate the proposed Islands Bond and associated repopulation challenges. The Orkney archipelago comprises 70 islands (Fig.1), 20 of which are inhabited (National Records of Scotland, 2013). During the 2011 and 2022 census period, the population of Orkney grew by approximately 2.9%, from 21,349 to 21,958 (National Records of Scotland, 2024a, 2024b). The longer-term picture (Table 1) is projected to be one of population decline. Disaggregating statistics for the archipelago based on the Scottish Government’s Scottish Islands Regions typology (R. Wilson et al., 2021) (Mainland Orkney and linked islands (those islands physically linked to the Mainland Orkney) and the ferry-linked isles (those islands without a physical link to Mainland Orkney) (Fig.1) shows that the demographic fortunes of these two geographical groupings have varied (Fig.2). As discussed in section 3.5., a repopulation initiative has been deployed in Orkney with limited success, but no studies reporting other efforts intended to stem further population decline in the Orkney Islands have been published.

4. METHODS

We now turn to discuss the methodology supporting the empirical work reported below. Ethical approval was awarded by the University of Aberdeen prior to data collection commencing. Eleven semi-structured, key informant interviews with fifteen participants were conducted between June 2022 and August 2022. The sampling framework used a matrix setting out desirable attributes of participants; individuals or organisations matching one or more of the criteria set out in the matrix and whose roles and contact details were in the public domain were identified and invited for interview. This sampling frame ensured that those invited to interview included individuals who lived on Orkney or lived on Mainland Scotland but whose work related to Orkney. They represented a variety of positions and roles including, for example, stakeholders who worked with or for public sector bodies including local (based in Orkney) and national government (based in Edinburgh), enterprise, economic, and housing supporting development groups, higher education institute, the National Health Service (NHS), local sustainability group management, and a youth organisation. As is common when researching rural development topics (broadly defined), some interviewees held multiple formal and informal roles in Orkney, meaning they could respond to questions wearing different ‘hats’ and, as a result, richer data were captured.

An interview schedule was designed to guide conversations that focused on three key themes: (a) the challenges to and opportunities for retaining and increasing population numbers across Orkney, (b) the strengths and weaknesses of past and present repopulation initiatives, and (c) key criteria for successful initiatives that help stabilise and increase population numbers. All interviews were carried out remotely, ten through the video-conferencing platform Microsoft Teams, and one over the phone (due to digital connectivity challenges). Whilst in-person interviews are considered the ‘gold standard’ (McCoyd & Kerson, 2006), online data collection was resource-light and increased the diversity of interviewees by allowing the recruitment of geographically dispersed participants (Iacono et al., 2016). A thematic analysis approach was adopted to interrogate the interview transcripts (Cope, 2003). The analysis was guided by a codebook containing themes which emerged during the literature review (deductive themes) and new themes that emerged during the analysis (inductive themes). We now turn to explore the findings from this study, which have been categorised into three groups.

5. FINDINGS

This section presents key themes arising from the analysis of interview transcripts. Findings are organised in three parts: (a) factors identified as constraints associated with repopulation in Orkney linked with community resilience, adopting the stance that repopulation can lead to increased community resilience, (b) interviewees’ reflections about strengths and weaknesses of the proposed Islands Bond, and (c) lessons from the international context to support community resilience.

5.1. Repopulation constraints in Orkney

The challenge of increasing and retaining populations across the Orkney Islands is complex and multifaceted. Demographic, socio-economic, and physical infrastructure challenges are interwoven; any initiative intending to support repopulation must be based on an understanding of these linkages. As one interviewee noted, it is “not one [issue …] it’s a combination of different factors” (Local Authority Representative 5). In particular, housing, transport, and digital connectivity were identified as repopulation constraints by interviewees. These interlinked themes are now discussed.

In Orkney, as is the case in many rural communities across Scotland, there is a lack of housing for rent and purchase whether it be family homes or smaller residential units. According to Economic Recovery Organisation 2 “[The population has] flatlined a little bit for [20]20 to [20]21. There has been such a period of huge growth and the reason we think there has been flatlines is because of the housing issues.” The shortage of housing of any type is associated with other challenges, such as retaining existing populations and attracting newcomers to fill labour market shortages. For example, NHS representative 1 noted: “Challenge number one is housing (…) the housing market in Orkney is just really imbalanced at the moment. (…) we have doctors [and] nurses who want to live and work in Orkney who are unable to find housing.” As well as hampering recruitment to key jobs, the housing issue also affects the recruitment of prospective post-graduate students planning to study a course delivered from one of the two higher education institutes with a presence in Orkney. Higher Education Provider Representative 1 said: “we are sending potential students [and] applicants away because there is no accommodation for them here in Orkney. So they’ll go somewhere else.”

Economic recovery organisation representatives discussed the variation in housing needs across the Orkney Islands. For example, one island is developing one and two-bedroom flats to encourage young islanders to remain there, whereas other island communities need families to keep the school open, so they are focusing on family accommodation. New housing units are being developed in some locations. However, in the ferry-linked isles, the scale of development is hindered by a lack of contractors and skilled trades. Further, Local Authority Representative 2 referred to the additional costs incurred by having to transport building materials by ferry from the Orkney Mainland to the ferry-linked isles and the impact of recent global events, such as the increased cost of materials and delays in international supply chains associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, presenting difficulties to any new housing developments.

The cost and timing of public transport services (ferries) within the Orkney archipelago were identified as barriers to retaining the population, especially in the ferry-linked islands. Youth Group Representative 1 and NHS Representative 1 noted that there could be ferry timetable issues that made it difficult for employees to travel from some of the ferry-linked isles to work on the Orkney Mainland. Nevertheless, ferry timetables were not felt to be a barrier to commuting to Mainland Orkney on all the ferry-linked isles. As noted by the Local Economy and Development Organisation Representative 1, the service to one ferry-linked island is timetabled to enable residents of that island to reach the Orkney Mainland and its employment centres for the start of the working day. This illustrates the importance of understanding local contexts and how they could mediate outcomes of any pan-Orkney population policy.

The third barrier to repopulation identified by interviewees was digital connectivity. Without fast, reliable internet access, prospective in-migrants can be deterred from moving to a rural location. Economic Recovery Organisation 2 observed that “There was speculation that the population growth over the last few years was because suddenly people realised they could work from home.” However, working from home, as an employee or if self-employed, increasingly relies on good internet connectivity and information and communication technology skills. For example, Local Authority Representative 2 noted that “More people would [move to the ferry-linked isles] if there was better broadband.” However, according to interviewees, there are still locations across Orkney which have poor, unreliable, and/or expensive access to the internet.

5.2. Reflections on the Islands Bond

Presented as an approach which aimed to help people make long-term lives in island communities, interviewees were asked to review and reflect on the Islands Bond proposal and consider whether it could stem depopulation within (a) Scotland’s island communities in general and (b) the Orkney Islands in particular.

5.3. Perceived strengths of the Islands Bond

A strength of the proposed Islands Bond articulated by participants was that it represented a recognition from the Scottish Government, based in Edinburgh, that depopulation is an issue across the Scottish islands and, importantly, that it offered dedicated funding from the Scottish Government to support island repopulation. Unlike other funding initiatives, which direct monies to communities or organisations, the Islands Bond would offer grants to individuals/households. A Local Economy and Development Organisation Representative 1 thought that the scheme “could be useful to keep people on the island. (…) for families that have had to leave, maybe a bond would have (…) helped them,” an insightful observation given that much of the repopulation literature assumes population revival is predicated on attracting new residents. Finally, Local Authority Representative 4, while generally opposed to the idea of the bond, considered that a potential justification for such a scheme could be in covering the additional costs of building houses on islands compared to elsewhere.

5.4. Perceived weaknesses of the Islands Bond

Interviewees felt the Islands Bond would have limited success in increasing and retaining populations in Orkney: “We don’t think it will work, to be perfectly honest” (Economic Recovery Organisation 1), while others thought that the Islands Bond could have a short-term impact. For example, Local Authority Representative 5 said, “I think it will temporarily increase population by a very, very small number, because we’re talking about a handful of folk who would make use of this money.” In the specific context of Orkney, the Islands Bond could be more beneficial to some islands than to others. Local Economy and Development Organisation Representative 1 observed “Potentially there is a difference amongst isles because of the availability of housing stock and jobs. (…) The Bond may work better on the Mainland where there is a greater housing stock compared to the isles.” Suggesting wider concerns about the lack of clarity in the proposal regarding who would be allocated the funding and for what purpose and alluding to concerns that people on the ferry-linked isles may use the Bond as an opportunity to move into the island’s capital, Kirkwall, exacerbating depopulation in non-Mainland Orkney.

Some interviewees perceived that the proposed Islands Bond could create an unfair advantage for recipients. Offering a financial incentive to someone moving into a community was considered unfair to existing residents. Furthermore, the Islands Bond proposal would see grants given to people moving to or already living on islands currently threatened by depopulation; the communities it would target are already sparsely populated, and an outcome could be the creation of divisions between established and new residents. For example, Local Authority Representative 5 stated, “I think [… the Islands Bond] is detrimental to really small communities. It will cause a lot of friction [and lead to] a really unhappy social situation.”

A feeling that the Islands Bond would not tackle wider challenges and issues currently facing island communities was also mentioned by interviewees. The focus of the bond on financial support to individuals/households before addressing housing and connectivity challenges was highlighted as an issue requiring attention ahead of offering financial incentives. Local Authority Representative 4 noted, “Until the infrastructure is in place, the housing [and] the connectivity, the islands can’t necessarily support [… new residents …] you need to invest in infrastructure and people will follow.”

A view that the Islands Bond would not address population challenges over the long term was summarised by Local Authority Representative 5, who said:

It’s a one-off, tokenistic gesture that won’t actually make an impact long term, and when you’re talking about populations in islands, you’re looking at the long-term game. (…) If you’re parachuting in people with a gift of money, I just can’t see that being a long-term increase in population, because I do think people will probably leave. In my opinion, the kinds of people that stay in islands aren’t here for the money.

The views expressed by interviewees clearly identify that addressing population decline and boosting island population requires more than financial incentives. Could lessons be learnt from elsewhere that could inform alternatives to the Islands Bond? We now turn to consider the views of Orkney-based stakeholders and those based elsewhere but with a stake in Orkney towards approaches to repopulation introduced in other places where there are similar challenges to those facing Scotland’s islands, which have the potential to inform future Scottish islands repopulation initiatives.

5.5. Opportunities from the international context

Interviewees were invited to express their views about the transferability of selected international repopulation approaches to an Orkney context. The examples described to participants by the interviewer during the conversation were Denmark’s Bosætningssservice and Maine’s Fellowship Programme, both outlined in section 2.4. These examples were selected because the population-related challenges they are attempting to address align well with the challenges faced by many of Scotland’s island communities.

Interviewees recognised the value of a support service such as Bosætningssservice, an initiative which helps new and potential residents find homes, education opportunities, and jobs and establish networks. In an Orkney context, Higher Education Provider Representative 1 said, “I think it is something that would definitely benefit a place like Orkney, which has been really well documented in terms of its challenges with accommodation.” Another interviewee thought that such a service could play a role in retaining people by helping to ease some of the challenges associated with island life, avoiding a situation described as “that circle of people come, they don’t like the winter, leave, and that continues” (Scottish Government 1).

Views about translating the Maine Fellowship programme to an Orkney context were mixed. Local Authority Representative 1 thought: “It sounds like it could be a useful mechanism”, and Local Authority Representative 5 felt “it would help stem depopulation across the whole of Orkney.” Others were negative, for example: “I feel [… it is] a paternalistic example that somehow the knowledge exists outside of Orkney to solve Orkney’s problems” (NHS Representative 1) and

I wouldn’t have thought the idea of dropping in a graduate to come and tell [… islanders] what to do would go down terribly well (…) It does sound a bit like something [… a regional newspaper] once described as bringing civilisation to a third world country, which never went down terribly well (Local Authority Representative 4).

6. DISCUSSION

Findings from the interviews point to six Principles of Repopulation Initiatives for Community Resilience (Fig.3), which may help address repopulation constraints (see section 5.1) and support community resilience. They fall under three key themes: (a) principles of retaining and supporting population and in-migration, (b) place-based principles of initiatives design, (c) and principles for measuring success. These principles, as well as examples of how they may be incorporated into repopulation policy, are now discussed.

6.1. Principles of retaining and supporting population and in-migration

Participants anticipated that divisions would arise between those who received and those who did not receive Islands Bond monies, potentially exacerbating any long-held tensions between ‘locals’ and ‘incomers’ (Jedrej & Nuttal, 1996) and inhibiting attempts to successfully integrate new residents into small communities. This potential for divisiveness, in turn, could compromise the aim of the Bond to help people make long-term lives in island communities (Scottish Government, 2021b). If those arriving at a new-to-them community struggle to integrate well and fail to develop a positive relationship with their neighbours and other community members, new arrivals may disengage from the community, minimising the opportunities for social interaction, which may lead to their decision to leave (Nordberg, 2024).

Interviewees’ assessment of international repopulation initiatives in the Orkney Islands context suggests that a support service designed to help migrants or potential migrants to find homes, education opportunities, and jobs and establish networks (such as the Bosætningssservice) could help stem depopulation and increase population numbers across the Orkney Islands. As well as addressing issues of housing availability, such a scheme could help to prepare new residents for the ‘reality’ of island life, such as the practicalities of living in a small community, the necessity of relying on ferry services, and having to cope with harsh weather conditions. Since these challenges are not unique to Orkney, such an approach is likely applicable beyond the Orkney Islands in supporting community integration, cohesion, and resilience. This aligns with Wilson et al’s (2018) assessment that “temporary migrants (…) should be encouraged to integrate locally without upsetting embedded economic, social, cultural and political domains too much” (p. 381) to help ensure that in-migration supports community resilience.

6.2. Place-based principles of initiatives design

Those interviewed felt that the Islands Bond, as a financial incentive, was not an appropriate means through which to attract new residents to the Orkney Islands because it could potentially attract the ‘wrong people’ and/or only have a short-term impact. A potential approach to attract the ‘right people’ and increase community resilience could see such funding being ringfenced for individuals with skills that would address local labour market needs or boost community social capital. This is where features of the Maine Fellowship programme could be incorporated into any future island repopulation initiative. The Maine programme is available to those with a degree. However, where attracting individuals with a degree, such as teachers or nurses, is not going to create the greatest community resilience, a Scottish Island Fellowship could instead be targeted towards individuals with labour market skills identified by the community as being in short supply, such as skilled trades (plumber, electrician, etc.) or those with the experience required to fill a social care vacancy. It could also support people who have the necessary skills ‘to do well in the islands’ and who can integrate into the community. Aligning with our understanding that islands are unique places (King, 2009), identifying who the ‘right people’ are for the community is complex, in part because what makes someone the right person is likely to be geographically and time fluid, as the capacity and needs of the community vary and change (Gow et al., 2023). To successfully build community resilience, flexibility in place-based approaches is needed as “resilience is a long-term societal process balancing a variety of needs, not a directly measurable one-off snapshot” (Kelman, 2021, p. 117).

The findings in this study suggest that for a Scottish Island Fellowship approach to be most effective, modifications to the Maine scheme would be required. To avoid conveying the impression that island communities need outsiders to help them solve their problems, any fellowship scheme would need to be sympathetic to the area it is operating in and be designed in such a way that the needs of specific communities could be accommodated. In addition, with some islands experiencing population growth and increasing resilience without any initiatives being in place to attract new residents, a fellowship scheme should only be available on islands where future in-migration without initiatives would be unlikely. To address the weaknesses of the Gateway Homes initiative seen in the Orkney Islands, a medium-term perspective would require a fellowship scheme, which had a planned end date, to be available on islands where, at the end of the fellowship period, those who came on the back of the scheme would have a realistic chance of securing employment and housing that would allow them to stay on as island residents. Finally, it is recommended that a mechanism be introduced to support those already living on the island to determine who the beneficiary of the fellowship is and what the fellow’s remit is. This may help to avoid the dilemma of outsider-looking in (Baldacchino, 2008) and achieve the greatest community benefit.

6.3. Principles for measuring success

Examples of successes and weaknesses of population change policies are patchy and overly reliant on simple growth or population decline metrics as measures of success; they fail to capture the importance of community resilience. For example, Argyll and Bute Council’s evaluation of the RRF initiative, described in section 2.5, deemed it successful because it attracted 53 new island residents. However, is the number of new island residents the only metric that matters when it comes to repopulation initiatives and supporting community resilience? Repopulation policies need to go beyond a focus on increasing the number of people living in a particular place. They must incorporate and explicitly seek to address wider issues associated with depopulation and aim to support community resilience. In this study, for example, interviewees noted the Islands Bond did not address the well-documented issues driving out-migration from and discouraging in-migration to rural and island areas in Scotland. Prominent amongst the drivers are challenges in local housing markets (Scottish Rural Action, 2019), including a lack of housing units, a lack of housing units suitable for different types of households, and a lack of affordable housing (all exacerbated in many islands in recent years by the increasing proportion of holiday lets (c.f.Gow & Philip, 2022). Further, repopulation policies should explicitly consider who should be attracted to live, and probably work, in islands where a boost to the resident population is required. Successful initiatives could focus on attracting people who may have the greatest impact on community resilience, i.e., the ‘right people’ (R. Wilson et al., 2025). These could be people who can fill key labour market gaps (such as teachers, medical professionals, and skilled trades), come with young children who will boost the local school roll, or who, if no longer economically active, bring with them skills and expertise. Some of these underlying principles have been addressed in a recently announced initiative involving the organisation Llwyddo’n Lleol and local authorities covering the traditional Welsh language heartland. Couples and families can apply for up to £5,000 to encourage a move to areas facing significant Welsh language decline due to long-term out-migration. Compared with the Islands Bond, eligibility criteria are clearly specified (BBC, 2024), criteria which include existing Welsh language skills or a commitment to learn the language. Any future evaluation of this new initiative should consider success in the context of having clearly specified eligibility criteria.

7. CONCLUSION

Using the Orkney Islands as a case study, this paper aimed to understand what lessons could be learnt from the Scottish Government’s Islands Bond and other initiatives to inform any future repopulation initiatives in the sub-national islands, specifically highlighting some of the underlying principles of these initiatives and the way in which they contribute to resilience. Of particular novelty, our findings identify six underlying Principles of Repopulation Initiatives for Community Resilience which could help address population decline and boost island community resilience. Recognising these underlying principles at different stages of policies, e.g., setting aims, designing initiatives, and measuring their success, provides a novel way of more effectively supporting resilience in Scotland’s islands.

Our findings suggest that addressing depopulation requires more than financial incentives alone. There are wider issues to island depopulation at play, which require infrastructural and cultural dimensions to be considered alongside financial barriers. Our findings also showed that other repopulation initiatives, such as the Denmark Support Service and the Maine Fellowship Programme, could have success in Scotland, although the latter would require geographical fluidity in its design so as to be culturally acceptable and recruit the ‘right people’ for the island, potentially through a Scottish Islands Fellowship. The constraints to repopulating islands are shared with other island groups in Scotland, and indeed with other nations; as such, the findings presented in this paper are likely to be applicable beyond Orkney and Scotland.

Examples of success and limitations of repopulation policy are patchy, but through observation, facilitation, and policy scrutiny, academia has a role in helping to address challenges associated with depopulation. Further case study-based research is required to understand the nuance of what is needed in different places, who the ‘right people’ are, and what other underlying principles need to be unearthed so that more effective, future-proofed repopulation initiatives and solutions can be developed while improving community resilience. By improving our understanding of these differences, more effective policy interventions can be designed that have a greater chance of achieving resilient communities in Scotland’s islands.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all those who participated in this research for their insightful reflections they offered during interviews. The strength of the data in this paper is due to them and their openness during these conversations. The authors thank Jamie Bowie and Jennifer Johnston for producing the map presented in Figure 1. The empirical work reported in this paper was funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council collaborative doctoral studentship (grant number ES/P000681/1). Currie’s and Wilson’s time was funded by the Scottish Government’s Strategic Research Programme 2022–27, JHI-E2-1, as well as Underpinning National Capacity Funding. Also, thanks to the two anonymous reviewers of this paper for their thoughtful and helpful comments.

For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CCBY) [or other appropriate licence] to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission."

.png)

.png)