Islands simultaneously suggest “confinement and freedom, isolation and connection, over- and underdevelopment, inclusion and exclusion”

(Kennedy & Fresno-Calleja, 2023, p. 1)

1. Islandness and Cypriotness

Whatever “islandness” is, the consensus among scholars is that there is great diversity among islands to justify a common and coherent perspective that can be applied to all (Hay, 2006). Their only similarity seems to be the fact that they have occupied a powerful place in modern Western imagination, lending “themselves to sophisticated fantasy and mythology” (Baldacchino, 2005, p. 248). For Cyprus, islandness is closely linked to a sense of Cypriotness and how Cypriot identity has been imagined and has invariably shifted over time, especially in relation to colonial and postcolonial frameworks. Throughout the island’s modern history, islandness and Cypriotness were both defined by political struggles, economic instability, inter-communal conflict, and a contrasting thriving locality that often remained unrecognized and un-sketched. They were also defined by mythologizing and imagining the island, through texts and images, in contrasting terms of otherness, exoticism, idyllic paradise, modernization, and resistance.

During Ottoman rule, for instance, and until the early 19th century, the island was depicted as an uncivilized and barbaric place, an image carefully cultivated by the British. By the early to mid- 20th century, Cyprus was reimagined and promoted in photographs, postcards, films and travel guide illustrations as either a primitive, thus, unspoiled paradise, or a romantic and exotic destination for tourists, (Daskalaki, 2017). Gradually other forms of iconography emerged that showcased an “appealing combination of leisure and modernity” (Pyla & Phokaides, 2020, p. 30). For Cyprus, tourism and relevant promotional tactics that illustrated the island, and especially its beachfront, as glamorous and luxurious were employed to prove that the island could compete the Euro-American standards of the hospitality industry (Pyla & Phokaides, 2020). This was at a time when late capitalism tied global mass tourism to wider processes of island modernization (Hong, 2020) and to the revitalization of their economic significance (Balasopoulos, 2008).

By the 1960s and after independence, a flourishing consumerist society celebrated its newfound liberation by seeking economic prosperity and an affirmation of a new identity through radical modernization (Daskalaki, 2017) and distancing itself from colonial traditions (Pyla & Phokaides, 2011). Pyla and Phokaides call this a “euphoric post-independence boom” (2020, p. 30). This seems to follow global postmodern reinventions of the island imaginary that according to Balasopoulos (2008) were fostered by the “influential iconicity of the photographs of the earth generated by the Apollo missions” in the late 1960s and which produced “a pictorial language of the global that highlighted the ocean-dominated, islanded status of the planet earth, surrounded by the silent, hostile blackness of outer space” (2008, p. 18).

The island became a marketable fantasy that masked ongoing inequalities and the legacy of imperialism. Pyla and Phokaides (2020) also argue that the laid-back iconography produced for tourists after the 1960s masked the complex socioeconomic and political realities of the island. The lives of Cypriots were marked by residues of the anti-colonial struggle of the 1950s, social division of left-right ideologies, as well as the polarities between the two main communities of the island’s Greek- and Turkish Cypriots, which led to inter-communal conflict and a search for settlement to what became known as the “Cyprus Problem” (Pyla & Phokaides, 2011, 2020). Ultimately, these conflicts led to the 1974 coup d’état and subsequent Turkish invasion resulting into the island’s violent division (Papadakis, 2005; Pyla & Phokaides, 2011, 2020) that left the island with a deep national trauma. still ingrained in its discourses and collective consciousness.

More recently, the island has been portrayed as a haven for tax evasion in the Mediterranean. These characterizations of the island, often the result of colonization, the imperial gaze, and external views, have also shaped the ways in which locals have imagined themselves and often coexist in present identity narratives. Sometimes, the contradictions between such representations shape an unstable and evolving definition of identity and islandness that remains in flux, with its origins and formative processes obscured.

Shifting notions of identity are also informed by the fact that Cyprus has been caught between the competing desires of mainland Greece, mainland Turkey, and the British Empire. One’s positionality and allegiance to these external forces, often perceived as “motherlands” by different communities of the island (Papadakis et al., 2006), shape and impact on a shifting sense of Cypriotness and define the island’s evolving image. This also unsettles linear historical narratives. Historical continuity and a perceived natural innocence of island enclaves are notions often ascribed to small, near-shore islands that are subject to processes of othering by the “ultimate big Other” or by mainland imaginaries that construct utopian paradises both remote and accessible (Hong, 2020). In the case of Cyprus, the absence of a fixed mainland from which the island can be viewed or studied creates a complex web of relationships and historical trajectories, making the notion of a linear historical narrative an even greater paradox.

More so, and despite its longstanding portrayal as an exotic destination in the wider imagination of imperial powers and the tourism industry (Daskalaki, 2017), the island’s lack of a fixed mainland sets it apart from the study of other islands, for it has always remained peripheral to all three of its potential “motherlands.” Even after gaining independence, the island never transitioned into a recognized island center. Instead, it remains a contested space, often defined by its division, peripheral status, and postcolonial legacies, felt in areas of law, administration, and infrastructure (Bryant, 2006) to this day.

The concern, then, becomes about how we might unpack and unravel those processes that inform and are informed by a sense of islandness as a defining concept in the formation of Cypriotness, and which is shaped, maintained, restated and reproduced through repeated “utterances, images, and meanings” in a performative way (Lin & Su, 2022, p. 48). Of course, in island imaginings as in all representations, the position of the narrator is of significance, as much as is the question that Baldacchino (2008) raises for the study of islands: “on whose terms?” This aligns with a postcolonial call to recognize islands as active agents capable of challenging and reshaping the hierarchical systems through which they have traditionally been governed (Fletcher, 2011). It is also aligned with those arguments that challenge problematic categorizations of islands as “small” or “warm” attesting to taxonomic subordination (Baldacchino, 2008) and which ultimately impact on falsely perceiving island identities and islanders as vulnerable (Foley et al., 2023). Certainly, as Balasopoulos (2009) argues, any attempt at producing a postcolonial island discourse should take into consideration the polarity and tensions between the technocratic conceptualizations dominated by the global markets and the culturally situated constructions, where the agency of the island-colony is of significance.

This paper, although it acknowledges such tensions, aims to specifically shed light onto those culturally specific readings and imaginings of the island from within, that emphasize the significance of locality in processes of decolonization. These refer to ways of unsettling and undoing existing island imaginaries and conventional readings of local history. Such critical awareness turns our attention to power relations and / or authoritative positions and knowledge expertise that might have resulted in what Foucault called “subjugated knowledges” to describe those alternatives, in our case, site-specific islanders’ views that were historically marginalized, silenced or erased (Bluwstein, 2021; Foucault, 1980). Michael Given, when discussing Cypriot archaeology, similarly turns our attention to the agency of local knowledge “practiced through being in the landscape, in a complex and constantly emerging relationship with community, [and] ecology” (2025, p. 35).

Similarly, this paper’s emphasis turns on the investigation of how contemporary artistic practices from the island can play a pivotal role in re-making islands by being in the landscape, offering new counter-readings of colonial legacies and establishing new imaginings for the island. In this context, visual engagements can unearth those local voices and spatial experiences that potentially challenge the ways in which the colonial gaze has produced knowledge and visual discourses about the island, considering “itself over the landscape” that repeatedly objectified (Given, 2025, p. 35). In further examining these imperial legacies and their impact on the fluid and ever-evolving narratives of island ecologies and sense of local identity, this paper specifically engages with photography and its role in shaping the images of the island historically as well as through the work of contemporary art practices.

The work of Cyprus-born, Cyprus-based artist Stelios Kallinikou is used as a case study. Kallinikou’s work was selected for it variably explores contested landscapes and the island’s colonial past through photography and by means of wandering in the land. His work is examined in the framework set by Melissa Kennedy and Paloma Fresno Calleja when discussing literary works and textual representations: as a movement towards intervening, revising and re-contextualizing the making of islands through specific island experiences and lived realities that offer “alternative discourses necessary to counter western, Eurocentric and neoimperial island imaginings” that “relegate islands to periphery status and marginalize islanders” (Kennedy & Fresno-Calleja, 2023, p. 2). This shift of direction, and the marking of the process of making and unmaking as continuous and incomplete is discussed in the following sections by adopting the term ‘trope’; the trope of the island and the trope of photography.

Finally, this process of making and unmaking our understandings of Cyprus by means of contemporary photography also refers to the unearthing of relationships that offer a multilayered perspective of the island, and it is closely linked to artistic photographic practices as an act of (diss)assemblage (Sather-Wagstaff, 2011). Sather-Wagstaff (2011) uses the term (diss)assemblage to highlight how our embodied experiences with charged and contested spaces, through walking and taking photos, can often unravel the intended official narratives by means of clashing with personal, potentially competing narratives, and imaginings. The notion of (diss)assemblage is particularly adopted in further analyzing Kallinikou’s ongoing project on the Akrotiri peninsula, an area of both archaeological and ecological significance, which is still under British governance. The analysis of Kallinikou’s works through the lens of (diss)assemblage provides a method for specifically tracing how island imaginaries (the island trope) are constructed, layered, and dismantled in contemporary artistic practices through photography (the photography trope). In effect, the notions of trope and (diss)assemblage, when viewed together, highlight the island as an active process rather than a fixed location

2. Making and Unmaking Islands: The Trope of the Island and the Trope of Photography

The term ‘trope’—from the Greek tropos which means a turn, a change, a direction—is adopted in order to speak about the processes of making and unmaking islands and their representations (the trope of the island) in colonial and postcolonial frameworks. The island trope is thus approached as the process of construction and representation of Cyprus’ landscapes in such a way that, according to Daskalaki, uncovers how landscapes “can become an instrument for asserting ideologies and shaping identity” (2017, p. 1). In this paper, such shifting is viewed in relation to the production of the photographic image (the trope of the photograph) and how photography has been adopted historically and in the present in processes of making and unmaking the island.

More specifically, the notion of trope is used for discussing the island and the ways in which a very specific sense of islandness emerges from images, in this case photographs, which in turn are linked to their sociocultural context and can mark a turn in how we imagine Cyprus (and Cypriotness) in the present. Stavros Karayiannis (2014) is similarly using the term ‘gender trope’ when discussing gender as a notion that emerges from images in his chapter “En-Gendering Cypriots: From Colonial Landscapes to Postcolonial Identities.” He explains that he sees “the images as moving beyond the confine of their frames and into the domains of the sociological and cultural as they mark turning points and shifts in the ways we imagine particular subjects in various settings” (Karayiannis, 2014, p. 127).

Of equal significance, emerges the trope of the photograph for while photographs have been used as tools for imagining and re-imagining the island, photography itself can be seen as shifting, culturally and historically constructed, and imbued with meaning. It is expected that when unpacked in their relationship—island and photography—can potentially offer a new reading of decolonial practices and postcolonial imaginaries in relation to the making of islands.

The idea of trope further frames recurrent island imaginaries for an island like Cyprus, with a long colonial infiltration, by unpacking existing dominant perceptions, and deriving to counternarratives and meanings from within. The photographic work of artist Cyprus-born, Cyprus-based Stelios Kallinikou, whose practices turn the landscape of the island into a site of inquiry, using wandering and trespassing, are viewed as acts of resistance to, but also as acts of making and unmaking of both colonial control and its legacies on the environment. Having a background in archaeology, his work reflects an equally significant attempt to challenge other forces that have come to shape the island’s ecologies throughout its long histories of settlements, colonialism, and capital domination, and to ultimately disrupt such narratives. I will return to the analysis of his work later in the paper.

2.1. The Trope of the Island

Despite its small scale, but due to its strategic location in between three continents and resting above metal, minerals, and gas reserves, Cyprus, has long captivated the imagination of conquerors. Historically tied to the myth of Aphrodite’s birth offshore the city of Paphos, the island has been allegorically also associated with love and lust, desire, and beauty. This is arguably the case of smaller islands, whose representations in the western “storehouse of images and narratives” perpetuates and maximizes their “erotic potential of insularity and exoticism” in popular imagination (Kennedy & Fresno-Calleja, 2023). In the 19th century, such perceptions were often based on views of Cyprus as a pre-modern society and an unspoiled environment. Framed as an exotic paradise and depicted as such with various image-making technologies from drawings, postcards and then photography, Cyprus was subsequently gazed from the outside as a site of ‘otherness’ (Stylianou & Philippou, 2017, 2019). As Liz Wells argues, such romanticizations of the land and of the rural environment, “echo nineteenth century notions of the land as timeless, available, sublime yet tamable with persistence and endurance” (Wells, 2011, p. 110).

In addition, arguments about the environment being threatened by the locals’ lack of knowledge, unrestrained abuse, and “unchecked exploitation” of the land (Given, 2004) conveniently became a tool for justifying modern projects of domination and colonial control. When the British took over the administration of the island from the Ottomans in 1878, they found the island’s forests in a degraded state, attributed to years of plundering the land without constraint, including felling, clearing, and continual goat grazing that prevented forest regeneration (Given, 2004). In effect, on the one hand, the demarcation of the forests was a “very necessary step in rescuing them from destruction and neglect” (Given, 2004, p. 3). On the other hand, this was the first of a series of interventions on the landscape that marked imperial superiority over both the Ottomans, who preceded the British on the island, but also the locals, who in effect, were perceived as uneducated, ignorant, and uncouth. Such perceptions stood as adequate justification for a series of imperial projects that included, among others, an accurate mapping of the island, water infrastructures, a new type of governance, and the demarcation of land and its people into a set of identified units easily arranged and thus controlled (Given, 2004, 2025).

This systematic ordering of the island and its natural resources—its forests, rivers, and waters—as an instrument of colonial control, explicitly demonstrates how the island’s unique geology has been just as crucial as its strategic geography at the crossroads of three continents in shaping its historical exploitation. One striking example is the island’s copper mines and mineral reserves, from which Cyprus took its name, dating back to the fourth millennium BC, often referenced in several texts by scientists, geographers, and travelers from antiquity to the 15th century. The mines, left “abandoned and in ruin” by the Ottoman rulers, were seen by the British as a missed opportunity and an alternative to its agrarian economy that could help the revival of the island which by the 19th century was greatly impoverished (Kassianidou, 2025, p. 229). When the Cyprus Mine Corporation was established in 1916, the main aim was the exploitation of mining regions around the island. This ultimately led to the destruction of the ancient mines and copper workshops (Kassianidou, 2025).

Similar colonial practices of digging, mining, and drilling that greatly impacted on the island’s ecology can also be traced in the detailed records of Mr. R. Russell of the British Geological Survey (and others later), who systematically documented the water systems, as well as plans for drilling the island’s plains for the implementation of an irrigation system. Patrick Balfour in his 1950s The Orphaned Realm: Journeys in Cyprus writes:

British engineers, drilling for water in the depths of the sub-soil, building, pumping and channeling to direct the streams over the land, instead of into the sea, work hard to irrigate more of it (land). Believing that Cyprus is no place for large and elaborate barrages, they concentrate on a wide variety of small dams, cisterns, wells, weirs and channels, providing village after village with the means to grow more food. (1951, p. 201)

Such projects were at once “an infrastructure of Indigenous dispossession, a chronicle of racialized labor regimes, and a symbol of British imperialism” (Dang, 2021, p. 1007). At the same time, they marked the island as one of peripheral status. Cyprus was described as an underdeveloped island, a no-place for large and elaborate interventions, while the attempt for smaller projects aimed at offering solutions to the lack of efficient agriculture methods, economic sustainability and the need for improved living conditions. Such representations of the island had, on the one hand, a significant impact on landscape shifts, and on the other, a great influence on defining the island’s identity as one of otherness and marginal reality. This also explains how the island’s colonial histories are always linked to various processes of identity constructions, and how notions of national identity and islandness are more generally formed (Hong, 2020). Nonetheless, and often paradoxically to the above, one needs to also be aware of the ways in which “[i]sland spatiality sometimes encourages the collapse of internal cultural difference into a single, comprehensible representation of identity” (Lin & Su, 2022, p. 40), leading to the concealment of more complex relationships and alternative narratives in identity politics. Photography, despite its ability to document and to show, it can also become an instrument and a technology of control and power through patterns of representation that can potentially conceal complex alternative narratives.

2.2. The Trope of the Photograph

Photography emerged alongside the ongoing exploration and settlement of new lands, providing a means to visually control, scale, and organize the landscape, mirroring the political objectives of white suprematism and colonial expansion (Clarke, 1997). John Tagg (1988) extensively explored the intertwined histories of the modern state, its systems of control, and their relationship with photography. As already mentioned, Cyprus became a key subject of this colonial photographic gaze that embodied the desire to visually dominate and categorize the land (Stylianou & Philippou, 2019). It is within this context that the island was often depicted by the British as “half-oriental” and primitive, perceived as being “tainted” by prolonged exposure to the East during the Ottoman period (Philippou, 2013, 2014). Stavroula Michael eloquently speaks of how British imperialists showcased overzealous effort to de-ottomanise the urban landscape trying to “replace this ‘oriental’ element with a highly compromised vision of modernity and urbanity” especially showcased on, “concrete fountains and reservoirs (…) typically devoid of any ornament or cultural affiliation except the understated yet definitive colonialist imperial cypher ‘GR’ (Georgius Rex) or ‘ER’ (Elisabeth Regina)” (2024, p. 64).

The photographic album Through Cyprus with a Camera by British photographer and prominent Scottish traveler John Thomson constitutes perhaps the first systematic attempt to apply a Western photographic vision to the depiction and representation of Cyprus (Wells et al., 2014, p. 5). It also exemplifies how photography was used by the empire to unify geographical, economic, and ideological imaginaries (Osborne, 2000). Thomson visited the island in the summer of 1878 and, during his five months in Cyprus, produced around sixty photographs that were later compiled into two photographic volumes. By documenting the island’s unhygienic conditions, the lack of road networks, the poorly maintained harbors, and the people as impoverished peasants, while suggesting that female beauty was absent because of hard manual labor, Thomson was indirectly justifying the necessity of colonial intervention and control (Adil, 2014; Papaioannou, 2014). Through these images, the British could persuade the public that establishing a military base on the island served both the Empire’s and the colony’s best interests (Papaioannou, 2014). Even in images that might be viewed as aesthetically pleasing—sunsets, harbors, the Troodos Mountains—Thomson ensured they were accompanied by notes advancing “a kind of cultural imperialism” (Papaioannou, 2014, p. 20, emphasis in the original).

Photography’s ability to record, document and persuade—even seduce—by offering the illusion of an objective perspective, obscured power relations, as well as local specificities, struggles, and voices. Besides, progress and urbanity were viewed by the British as unattainable for the natives, overlooking a thriving local modernity at the turn of the 20th century (Stylianou & Philippou, 2019). In parallel with these representations, the island was often portrayed as a romantic and exotic locale in images produced by European travelers, photographers, geographers, and pseudo-anthropologists, with Maynard Owen Williams’ 1928 travelogue on Cyprus for the National Geographic Magazine being one such example (Adil, 2014; Philippou, 2014).

What is particularly striking is that this exotic and idyllic island imaginary, produced and circulated through photography, was deeply consumed and perpetuated by the locals. This can specifically be seen in photographs by modernist photographers George Lanitis and Andreas Coutas, who worked at the Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation (CyBC) after independence. Coutas also worked for the Press and Information Office (PIO). Their photographs, often producing a romantic vision of the island—picturesque landscapes, classical ruins, blooming fields—illustrate how these imaginaries were adopted by the State and how official narratives seemed dangerously aligned with the colonial gaze of previous decades. Even if this had its purpose of attracting tourists from Britain, it nonetheless established an image of an island that failed to speak of its multiplicities.

How, then, does one break away from the staging of the island in those terms to embody an alternative vision and visual aesthetic of the island in the present? In the next sections of the paper, the work of Cyprus-based, Cyprus-born artist Stelios Kallinikou will be used as a case study to further investigate the ways in which contemporary artistic practices can adopt photography in a critical manner, still adopting the aesthetics of landscape photography, yet remaining far from innocent or simplistic representations of the island.

Through sustained engagement with Kallinikou’s practice, in the period between 2019 and 2025, that included multiple studio visits and a series of extended informal conversations about his approach, photographic practices, and intentions, I here approach his artistic process as a form of research and a primary source of data. Following a practice-as-research framework, I treated his own selection of works from his ongoing research at the Akrotiri peninsula, along with our discussions around them, as part of what can be viewed as an evolving and ongoing process of knowledge-making. Building on this, the visual analysis of the selected material, photographs and video, concentrates on the content and subject matter of the images and on how these intersect with our continuous conversations and recurrent themes of island imaginings, ecological destruction, and colonial/postcolonial tensions.

From a portfolio of works produced in the context of the Akrotiri research that the artist shared with me, I identified two projects, Birdwatching and Flamingo Theater, for closer examination in this paper. Both projects engage directly with a British-administered area of the island with great archaeological and ecological significance. In the following sections, Kallinikou’s works will be approached as counterevidence of colonial island imaginings. Further examination attempts to investigate how contemporary photography could decolonize established images of the island, thus contributing to reconfiguring dormant narratives and to the making and unmaking of the island (island trope), as much as to the ways we perceive photography and its functions (photography trope) in the present. In doing so, there is an acknowledgement of local narratives and representations from within.

3. Unmaking Islands: Contemporary Photography as an Act of (Diss)Assemblage

3.1. The Akrotiri Peninsula

Stelios Kallinikou is a photographer whose work delves into themes of landscape and the island’s colonial past. His explorations often take him to contested, hidden areas far from the typical tourist’s gaze, where remnants of colonial histories linger. Camouflaged as a nature photographer and an avid bird watcher (as evidenced by a 2018 photographic series bearing the same title: Birdwatching), Kallinikou navigates spaces where entry is often forbidden. He is usually equipped with a camera and two memory cards: one for innocuous images of flowers to show the authorities and another for capturing prohibited shots of restricted landscapes (Lovric, 2024). Kallinikou’s practice rejects the notion of seeking permission. His defiance of borders by official authorities is a deliberate act that fosters both a critique of power and a spontaneous, idiosyncratic engagement with the natural environment.

This can be seen as a form of resistance to authoritative demarcations of the land defined by political alliances, military and monetary interests, as well as to the island’s symbolic allure as a border; after all, the coastline does remain an entry point and a border at equal measure. Peter Hay (2006) particularly identifies the centrality of the notion of the edge to the construction of islandness and discusses how the hard-edgedness of the shoreline, along with a subsequent sense of physical containment, greatly contribute to the construction of island identities. In their study of islands in literary fiction and non-fiction work, Kennedy & Frenso-Calleja also state that islands are sites of contradictions, as they can be “sanctuaries offering protection, secrecy, luxury, and self-realization, but [can be] also sites of enclosure, imprisonment, isolation, dehumanization, and punishment” (2023, p. 4). Their paradoxical, binary nature, embodying contradictory notions, is a key aspect of the island trope that has often validated, if not enhanced, colonial and neoimperial control on the grounds of fluidity and vulnerability. Kallinikou’s creative practice comes as a form of resistance to such discourses by reconfiguring the land as having its own agency.

During our discussions, Kallinikou often speaks about how he is driven by acute curiosity, aiming to uncover details often overlooked by visitors or the tourist eye, and wanting to reveal through his wanderings any subtle narratives embedded within the Cyprus terrain. His recurring visits, documentations, and attempts at unearthing layers of meaning through close observations and silent dialogues with the natural environment, remind us of the work of Fletcher (2011) and Crane and Fletcher (2016), who established the island trope and islands as performative geographies, granting them metaphorical agency. They argue that islands are not merely passive spaces, but active sites in the making and unmaking of both individual and collective identities. Moreover, islands influence and shape how they are represented, thereby playing a central role in the construction of meaning.

As if in constant dialogue with the natural environment, respectfully and patiently waiting for it to disclose its secrets (and to produce meaning), Kallinikou repeatedly returns to one particular location at the southernmost tip of Cyprus: the Akrotiri Peninsula. At Akrotiri (deriving from the Greek word akra, meaning tip or edge) the land extends into a small cape. This is a distinctive feature formed thousands of years ago when a rocky islet merged with the mainland, as the Kouris and Garilis rivers carried sediment, debris, and sand to their deltas. Flowing from the west and east respectively, these rivers created a double tombolo, connecting the once-isolated rock to the coast (Polidorou et al., 2021). There are different studies that showcase how the area evolved from a maritime space to an open bay and finally to a closed salt lake (in between the two tombolo) (Polidorou et al., 2021).

There are various things that are important in the study of Akrotiri as a single locality and which are essential to this paper. First, archaeological evidence at the Akrotiri indicates the presence of the oldest known settlement in Cyprus (if not in the entire region), at the site of Aetokremnos, dating back to the pre-Neolithic era (12,000 BP). This link of the island to the Mediterranean open sea and to forces of population movements, migration, settlement, and colonization, showcases both the significance of the island’s geography and its vulnerability. A concept that was exploited by colonial imaginaries. At the same time, such evidence establishes the Akrotiri Penninsula as a site of archaeological significance and how this might have been integral to defining later geopolitics and imperial agendas.

Second, one finds here evidence of the degree to which the island’s ecology has greatly shifted because of movements, settlements and later colonial interventions. Simmons (2009) specifically argues how settlers traveling from the open sea to the island and living as hunters-gatherers were detrimental to the extinction of mega-fauna, as well as of the pygmy elephants and hippos found as endemic species in the area thousands of years ago. Although some researchers remain skeptical, others agree that it is this small group of humans that were at least partially instrumental in—and might have—triggered the eradication of the unique hippopotami populations who were suffering ecological stress due to climatic change and were thus already on the verge of obliteration (Simmons, 2009).

A site of archaeological significance, the Akrotiri is also a site of contestation in the island’s modern history, for it hosts the British Sovereign Bases since the late 1950s: a British Overseas Territory on the island. These areas include military bases and installations/radars formerly part of the Crown colony of Cyprus and which were retained by the British after the island’s 1960 independence treaty among the British, Greece, and Turkey, ending years of British colonial rule. The territory still serves as a site of the UK’s surveillance-gathering work in the Mediterranean and the Middle East and is a station for signals intelligence and imagery intelligence through aerial reconnaissance conducted in the RAF (Royal Air Force) base in Akrotiri.

Above all, the Akrotiri Peninsula and its evolution are of great ecological and geological significance. The Akrotiri Salt Lake, once connected to the open sea, as depicted in various Venetian maps, is a wetland of major biodiversity and one of the most important wetlands in the eastern Mediterranean (Polidorou et al., 2021). It evolved during the Holocene period because of tectonic movements and climate change, and as presently a closed lagoon, is a stopover for flamingos in their migratory routes between Europe and Africa during the winter months. These birds can be seen as metaphors for travel but, more importantly, for mobility: a concept closely associated with the island, reflecting the continuous flows of movement, especially of transient bodies that migrate, explore, nestle, settle, and ultimately colonize the land.

It is therefore unsurprising that the Royal Air Force (RAF) has adopted the flamingo as the emblem of its Akrotiri station (Image 1). The empire’s military “birds” are thus likened to the resilient migratory flocks that repeatedly return to the Salt Lake and the surrounding peninsula, standing tall in the water. As a symbol, the flamingo helps naturalize the RAF’s territorial presence by presenting the base as embedded within the local environment and even being a guardian of it. This appropriation of native fauna subtly reinforces sovereignty claims, visually aligning the foreign military power with the island’s natural heritage and asserting an implicit sense of superiority and control.

Thus, when it comes to the Akrotiri peninsula, the parallels between ancient and modern times are unsettling. Seafaring and naval technologies are replaced by air force, planes, and helicopters, whereas the indigenous pigmy hippos and their ecosystems in danger of extinction are replaced by the bright pink migratory birds. It might indeed be wrong to analyze these first settlements in the context of modern readings of colonialism and imperialism, since ancient movement did not necessarily aim to colonize as part of a wider project of expansion through land domination. It was often the result of traveling, visiting, or settling for a short period of time, and an attempt at finding resources for survival. Nonetheless, there is one thing that seems strikingly common across time: the enduring legacies of control and power over the island’s landscape and resources, while the logic of elimination in settler colonialism, as Wolfe (2006) suggests, remains primarily entrenched in territoriality (the desire to access territory).

3.2. Flamingo Theater (2019)

Kallinikou approaches his investigation of this specific area with a methodology reminiscent of an archaeologist, possibly driven by his academic background in the field of archaeology. Instead of searching for artifacts or remnants of ancient civilizations, he meticulously searches for stories and evidence that initiate a problematization of normative island histories and imaginings. The role of the artist in disrupting is of significance here. As is his acknowledgment of the significance of the flamingo as a symbol through which he further examines the relationship between colonialism, ecology, and the island. In his video work Flamingo Theatre (2019), a collage of archival material collected from YouTube free-to-access videos and photographs, the artist juxtaposes contrasting images highlighting and disrupting notions of a seamless historical continuum.

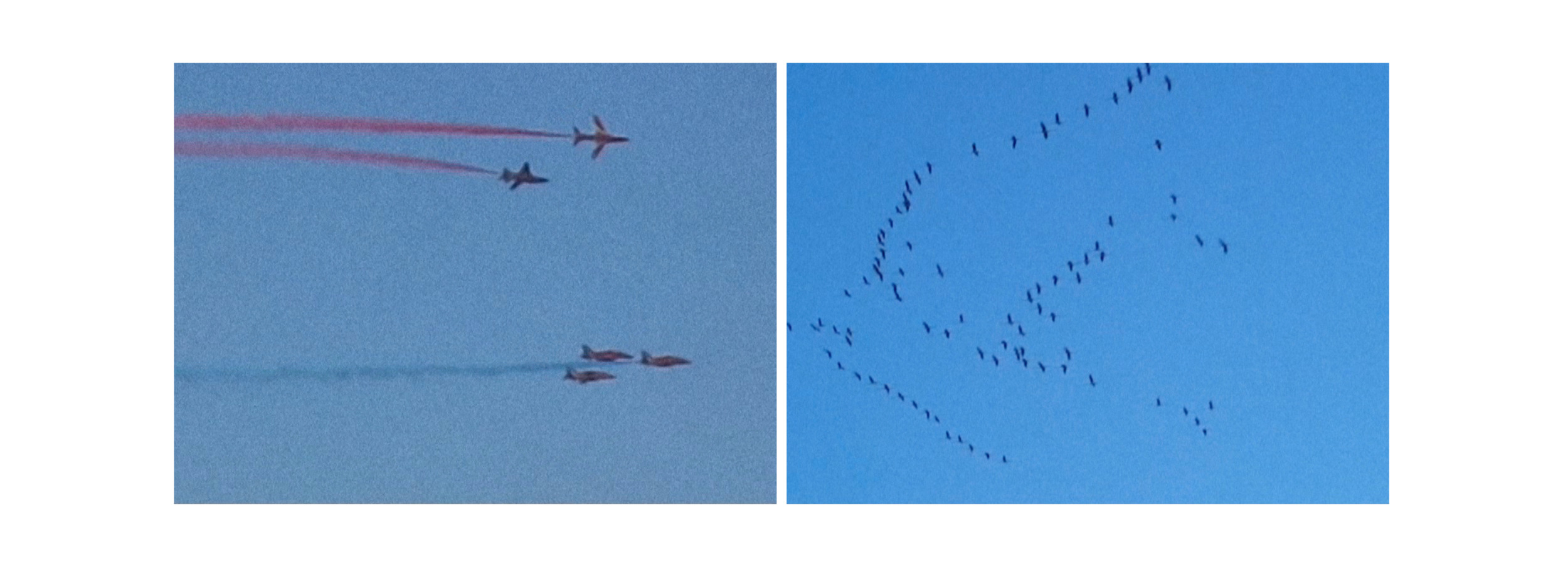

By exploring informal, idiosyncratic YouTube video archives, inspired by footage uploaded by adolescents who attended a summer school at the military base of Akrotiri, Kallinikou constructs an assemblage of narratives. The work is a collage of seemingly unrelated images. Young British soldiers in uniform are shown playing video games, spending their mornings and afternoons in what appears to be a carefree summer camp, rather than a military base. These moments are interspersed with footage of fighter jets flying in formation, possibly during military exercises or national celebrations in the area. These images are, in turn, combined with scenes of flamingos mimicking the flight patterns and paths of military planes, along with close-ups of insects, a lizard, a rescued turtle, dolphins, and indigenous plants.

Archaeological sites also feature throughout the video, referring to the longstanding romanticization of ruins by both locals and the imperial lens. On the one hand, such ruins have been instrumentalized to affirm the island’s ties to an ancient classical Greek past, sustaining an ethnic Hellenocentric sentiment that aligns it with mainland Greece and fuels a particular sense of national pride. On the other hand, these images also speak to the ways in which archaeological sites in colonized lands were visually and ideologically framed as evidence of a once great but now “ruined” civilization in need of the West. The West positioned itself as responsible for such worlds, which inspired and produced a rich repertoire of European pleasures, desires, and mythologies (Said, 1978). In turn, this imaginary was firmly and systematically established through both literary discourse and visual (photographic) representations.

In Flamingo Theater, however, ruins assume a different role. Juxtaposed with military exercises involving explosives, they can speak of the imperial project as one of ruination. Ann Laura Stoler (2013) describes this as an ongoing process that “brings ruin upon,” an “act of ruining, a condition of being ruined, and a cause of it” in discussing the ways in which we should consider the prolonged impact of imperialism and its enduring damage to lives in the present (p. 11). In her theories, Stoler urges us to understand ruins less as artifacts, dead matter, or “remnants of a defunct regime,” and more as a process that can be activated and reappropriated within contemporary politics (2013, p. 11). Under this critical lenses, Kallinikou’s images symbolically remind us of colonial domination and “exploitation of local resources and labor” (Abreek-Zubiedat & Phokaides, 2025, p. 606), warfare, and the enduring trauma embedded in the national psyche; all detrimental to the construction and performance of Cypriot islandness.

Parallel sequences in Flamingo Theater showing young soldiers engaged in morning drills, piloting fighter jets, dancing to the Macarena, or surfing the Mediterranean’s blue waters are starkly contrasted with footage of a forest engulfed in flames. This latter image evokes a different kind of ruin: one tied to contemporary ecological collapse and the consequences of human negligence. This can also be linked to more recent definitions of ruination that establish it as a form of an increasingly expanded act of imperial and capitalist “violence against humans and the environment” that encompasses the world’s unmaking and the planet’s ecological destruction (Abreek-Zubiedat & Phokaides, 2025). Ironically so, it is this type of negligence, ignorance, and “unchecked exploitation” that gave the British colonizers the excuse of demarcating the forests and mines of Cyprus in the early 20th century (Given, 2004, 2005). At the same time, fire was used as a form of systematic resistance to the imperial projects of domination, as locals would often use arson to push back at what they found a form of repression on their land and its ownership (Given, 2004).

Thus, in Flamingo Theater, the landscape—and its ruins—are reimagined to offer an alternative to dominant narratives, indirectly attesting to island imaginings as a paradise of ruins and archaeological wonderment, and critically questioning imperial justifications for scaling the land and its people in a certain way. Beyond the “heritagization and touristification” of the island’s landscapes, however, the island’s exploitation was also the result of “capitalist neglect and environmental degradation” (Abreek-Zubiedat & Phokaides, 2025, p. 606). At the same time, the cheerful and carefree youngsters speak of the lack of in-depth engagement with local struggles and ignorance of site-specificities, a common postcolonial critique. Moreover, the artist adopts the very medium that once served to promote, disseminate, and preserve the abovementioned Orientalizing perspectives to challenge both the historical account and the medium itself.

Whereas 19th-century photography catered to the European imaginary of superiority, in Kallinikou’s work it becomes a tool for fostering more layered and critical engagements with the island’s past and potentially unearthing the impact of colonial legacies in our perceptions of the island in the present. Photography is adopted as a means towards an avid engagement with what Liz Wells (2011) calls a “politics of environment,” primarily focusing on the uses of the land, now and historically. In effect, Kallinikou’s photographic work contributes to challenging and demythologizing Western over-simplified depictions of the land, questioning the ways in which western imperialism adopted photography.

3.3. Birdwatching (2023)

In his video work Birdwatching (2023) Kallinikou pays particular attention to the natural environment: the salt lake and its ecosystem, including the flamingos. These vibrant pink birds are photographed standing in stark contrast to the rapidly transforming landscape, where construction sites continue to spread, and towering red cranes dominate the horizon, casting their shadow over the salt lake. Juxtaposing the flamingos with the crane—also a name for another bird—these images attest to human domination over nature. Similarly, flamingos’ tall feet that are partly immersed in the muddy bottom of the lake and the occasional head dipping in the muddy water while filter-feeding on brine shrimp, echo the crane’s invasive metal legs on the ground.

At the same time, the antennas tower over the birds, their reflections on the surface of the water interwoven with plants and fauna merging unnaturally with the wetlands. This notion of filter-feeding alludes to that which is hidden in the ground, its muddy nature only intensifying the feeling that this area is riddled with difficult stories that are often obscured through political secrecy, lack of transparency, and governmental corruption. At once, nature is indirectly romanticized as pure and unspoiled at all odds, but not in the same way as it was historically romanticized as “other” and helpless. Here, nature seems to have the power to filter and clean, offering some form of hope for its potential to prevail.

On a different level, the title of the work, Birdwatching as in Flamingo Theater, leaves us with a sense of protagonism in a set stage where we ‘watch’ things manifest, reminding Edward Said’s (1978) seminal work Orientalism where he argues that the “idea of representation is a theatrical one” (p. 63). Said highlighted the performative nature of representation, for like theater, representations are selective, exaggerated, and arranged. As such, they are deeply entangled with hierarchies, power, and ultimately control—both physical and ideological. In Said’s writings, the Orient becomes the stage, as an enclosed space, affixed to Europe and its imperial interests and agendas. In a similar manner, Kallinikou brings forth the trope of the island as an enclosed space; a stage historically linked to ideological agendas and expansive politics, and which continues to remain subject to more recent waves of settlement and manners of representation.

One only needs to turn towards the east of the peninsula and very close to the lake to face the new casino in the area. The casino is a place where money flows for entertainment, a site where in popular imagination, illicit deals are made under the pretense of a gambling game, and a symbol for super-rich encounters of contemporary settlers in transit and the mega tourists. At once, this reminds Turner and Ash’s (1975) notion of the “pleasure periphery” in light of which the island becomes a newly found contemporary paradise for the constant search for “sea, sun, sand and sex” (Bonarou, 2021, p. 47). However, the casino equally manifests contemporary political and economic colonization that further destroys the landscape, gradually demolishing and destroying the nearby coastline and salt lake, and potentially invading and transforming cultural specificity.

All the while the photographed landscape becomes a stage of representational politics, the photograph itself is a political space (Azoulay, 2008). Ariella Azoulay discusses the civil contract of photography, claiming that while photography might appear to be the moment when all movement ceased, in fact, it attests “to action and continues to take part in it, always engaged in an ongoing present that challenges the very distinction between contemplation and action” (2008, p. 94). The photograph, as more than a mere record of what is made visible and closely linked to the very act of gazing, always holds the potential to show that which was not there, or that which was not there in a particular way, and occurring in a sphere of plurality (Azoulay, 2008). Photography can be seen as a political and performative space. Similar to the island trope, photography is a representation shaped by ideologies and politics, yet, in its contemporary manifestations, holding the potential of offering a discursive space for counternarratives. Kallinikou’s images offer a set of potential counternarratives to our imaginings of the island.

An added layer that contributes to the performative nature of his work and enhances alternative readings of the landscapes is his use of sound. In Birdwatching the recording of the birds’ choreographies in the lake, as well as their distinct honking sounds (especially at times when the waters of the lake are higher, and the numbers of the birds reach tens of thousands) blend with the noise caused by the planes and helicopters that fly to the nearby British military base. These sounds disrupt each other in a symbolically continuous attempt of domination—nature vs. man—as we, as observers, hope that nature will always win. Unintelligible to the human ear, sounds indirectly also reference the radio-listening over-the-horizon communication antennas that loom over the landscape since 2007, when the British Ministry of Defense caused controversy by constructing them in the RAF base. These are radar systems, known for their ability to detect targets at very long ranges, and are considered extremely harmful to wildlife due to their proximity to the lake.

Sound is quite significant to the work of Kallinikou, exactly because of its potential to speak of the inaudible. In a different work, Waterfall (2022), in collaboration with Tasos Lamnisos (presented at Xarkis festival in the framework of the project Contested desires), Kallinikou developed a performance which sonically activated part of Agros’ village water infrastructures developed during the British rule. During the performance, the water tunnels were transformed into carriers of radar sounds blending mantras and sacred syllables, hinting notions of visibility and invisibility, underground communication tactics, but also reminding us of our connection to the lands’ sounds.

Sounds have always been of significance or of spirituality in the ancient world and a way of connecting to landscapes. Garcês and Nash (2017) write of Stonehenge and other monumental ancestral landscapes and highlight how these locations were not merely visual but also audible through the resonant stones (ringing rocks producing distinct sounds when subjected to percussion), floating rivers, or deafening flows of rapids, making these sites a theater of performance. Kallinikou’s performative piece fabricates such sounds that are either of the land and of underground waters or artificial sounds transmitted through the water canals of colonial infrastructure, metaphorically resonating notions of historical formation and colonial domination over, as well as exploitation of, the landscape.

At the same time, these soundscapes, seemingly stemming from the earth’s womb, are like echoes of indigenous peoples, reminding us of the multiple histories of the land. They also contribute to shaping land into a narrative through the ways in which we experience it. Bound up in memory and mythology (Levi-Strauss, 1963 as cited in Garcês & Nash, 2017), our interpretations of the natural environment are enabled and activated by an embodied experience achieved through sound. This draws us in the landscape, and the artist seems to be reminding us of our deep connection with the land and how, in these experiences, we might understand it in alternative ways; in a process of making and unmaking from within.

4. (Diss)assemblage from Within

Kallinikou’s ongoing project in the Akrotiri Peninsula, both the photographs and the films discussed in this paper, problematizes the orthodox stories of and about the island. It also offers a critique of normalized definitions of the island as an isolated entity, allowing more fluid theorizations of the land (Gugganing & Klimburg-Witjes, 2021). At the same time, examining the island trope through the case study of Cyprus, via the lens of a local artist photographer, is an important analytical tool for disrupting assumed generalized understandings of the island. Unearthing Cyprus’ colonial legacies of representation, land exploitation, and resource extraction, while also challenging the historic legacies of photographic representations of the island, allows for the unmaking of established discursive tropes and shifts the ways in which the island can be perceived both locally and externally.

Beyond challenging the trope of the island and the trope of photography, the work also challenges processes of history-making, the latter an assemblage of perspectives, rather than a complete collection of linear narratives. Sather-Wagstaff (2011) argues relevantly that considering the selective nature of historical records, how these might change over time and in different interpretive frameworks, as well as the impossibility of history’s completeness by including all possible gained knowledge in totality, we might be better off speaking of assemblage and dissemblage: ‘(diss)assemblages’. She writes:

And historicity is thus inseparably intertwined with both memory and history; these are all part and parcel of the same social processes of coming to know about the past, crafting and re-crafting cultural (diss)assemblages over time. Historicities and memories are also histories in their own right, not completely separate from or always necessarily in position to a given official “History.” (…) Historicity (…) is a (diss)assemblage of knowledge taken from an array of sources including external sources, such as official historical narratives or others’ individual recollections and/or from one’s own memories of actually experiencing events. (Sather-Wagstaff, 2011, pp. 42–43)

In this context, Flamingo Theater, Birdwatching and Waterfall can be read as a (diss)assemblage that unearths invisible movements and relationships—exemplifying Azoulay’s notion of photography’s civil contract—and which quietly unfold over time, offering a layered perspective of the island. Here, the artist’s photographic gaze, artistic processes, and personal experiences and recollections from within become integral to this act of (diss)assembling that ultimately sheds light on the complex networks that manifest both in this specific area and across the island more broadly.

Expanding on the concept of the multiplicity in photography as much as on the fluidity in the formation of history, historicity and memory, Kallinikou’s practice also evokes the notion of “seepage” as described by 2019 Turner Prize artist Helen Cammock: “a slow but steady escape or drainage of one thing into another, a cycle of movement backward and forward akin to the dances of a tide” (Amirkhani, 2023). Through this lens, Kallinikou’s work on the Akrotiri Peninsula intricately intertwines both historical record and artistic practice with the fluid, ever-changing condition of water, while the position of the artist in the performative process of making and unmaking, assembling and (diss)assembling, is one of reclaiming the land and its histories.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Stelios Kallinikou for generously providing access to his work, images, and supporting material. Our discussions throughout this process were invaluable, offering insight and depth that significantly enriched this research.

_of_the_british_sovereign_bases_at_the_akrotiti_station.png)

_of_the_british_sovereign_bases_at_the_akrotiti_station.png)