Introduction

Accessibility describes the ease or degree to which a location is reachable from another location (Spilanis et al., 2012). Different approaches have been proposed to define, calculate and measure accessibility in a variety of scientific fields. Geurs and van Wee (2004) discuss the difficulties in arriving at a single definition that is both theoretically sound and operational. In this paper, we focus on island accessibility.

Island accessibility has been treated as a special case of accessibility, due to islandness, i.e. the characteristics that differentiate islands from continental areas and contribute towards an insular identity (Baldacchino, 2020). Several studies have attempted to quantify island accessibility (Andersen & Tørset, 2019; Cross & Nutley, 1999; Karampela et al., 2015; Makkonen et al., 2013; Spilanis et al., 2012), with approaches that include a variety of factors, such as transportation modes (ferry and air service), connection frequency, travel time, and land accessibility indicators. Literature suggests that island transport services influence the attractiveness of islands, their economy and quality of life (Agius et al., 2021; Cross & Nutley, 1999). According to Agius et al. (2021, p. 150) “islands are completely dependent on providers of transportation which shape their decisions in the best interest of shareholders and fail to adequately consider the challenges faced by such islands and their inhabitants.” They continue to state that “islands are more vulnerable than mainland when it comes to changes in transportation” (Agius et al., 2021, p. 150). For archipelagos, efficient sea transport is even more important (Grydehøj & Casagrande, 2020), as inter-island communication and transport is also involved (Hernández Luis, 2002) and different sizes, distances, population levels and economic activities of the islands within an archipelago are key to understanding and managing these complex networks (Destyanto et al., 2020; Sonny et al., 2015).

The issue of public policies for ferry and air services is therefore very important for islands, since the majority of islanders and visitors, but also businesses cannot rely on private means of transportation and have to rely on public ferries and airplanes to move to and from islands (Spilanis et al., 2012). This has been recognized by the European Commission (2008) that has stated that many islands have to deal with problems of accessibility, small markets, and high cost of basic public service provision and energy supply. Andersen and Torset (2019) discuss waiting times and accessibility in Norway and what they describe as ‘inconvenience cost’ of ferries due to waiting times. Angelopoulos et al. (2013) perform a cost assessment of sea and air transport in Greek islands, while Karampela et al. (2015) present some characteristic cases in the Aegean archipelago and combine ferry and air travel accessibility. Air transport policies and procurement of public air services for islands has received more attention recently than that for ferries. Fageda et al. (2016, 2017) discuss and present empirical evidence on European and Spanish policies of island air fares, Valido et al. (2014) further discuss subsidies for air fares in European outermost regions (almost all are islands), while Merkert et al. (2013) examine the efficiency of the procurement of public air services in the EU in general, and Wittman et al. (2016) compare EU and US air public service obligations. An important issue mentioned in all studies is the lack of transportation cost data (Makkonen et al., 2013). This transport cost to and from islands has been one of the most important factors mentioned by residents and business as well (Spilanis & Kizos, 2015).

Effective policies and management of transportation has to address these issues to achieve satisfaction and a long-term sustainability of services (Chlomoudis et al., 2011; Valido et al., 2014), including the two-fold issue of costs: the cost of a public policy that can ameliorate the extra transport costs that residents and businesses of islands face (Agius et al., 2021; Angelopoulos et al., 2013; Gagatsi et al., 2017). One of the policy concepts that has been used is the so-called Transport Equivalent or Transport Equivalent Threshold (TET). The TET concept was first introduced by Pedersen (1974) as Road Equivalent Tariff (RET) based on the principle that travellers to/from islands should be charged a fare similar to the cost of motoring a similar distance on land (Hache, 1987). In 1976, France provided maritime connections between the mainland and Corsica with a territorial continuity principle that aimed at eliminating maritime distance and insularity drawbacks and determined maritime transport fares by equalizing them to rail transport fares (2004/166/EC, n.d.). A similar RET approach for the remote islands of Scotland (Alexander et al., 2011) was applied in 2008 on the Western Isles. It involved setting ferry fares on the basis of the cost of travelling an equivalent distance by road, including a fixed element to keep fares sustainable and cover fixed costs such as infrastructure (Transport Scotland, 2012).

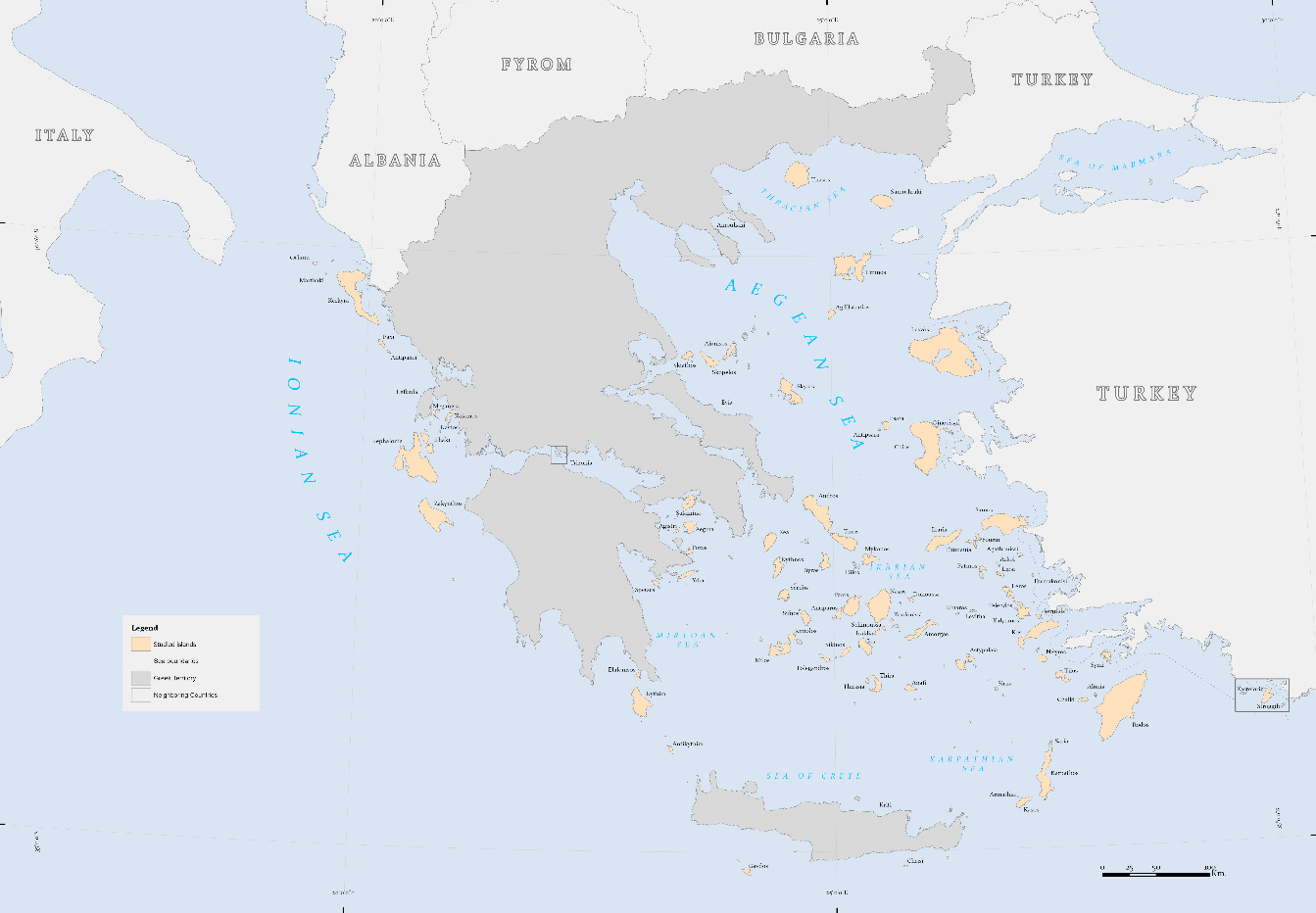

In Greece, the large number of inhabited Greek islands (Spilanis & Kizos, 2015) and the varying sizes of the islands and distances from Greek continental land (Figure 1) establish increased transportation needs to and from them. All these imply dependence on public ferry and air connections and higher costs compared to similar land distances. These are some of the reasons for the introduction of a TET approach in 2018. TET was defined as a policy tool “the adoption of which seeks to equalize the cost of transport corresponding to passengers and goods within maritime mass transit with the cost that would apply to land transport for the same distance” (Government Gazette 116/A/02-07-2018, 2018). Its geographical scope includes all islands except some very small ones, Crete (due to its large size), Evia, and Lefkada (which are permanently linked via bridges to the mainland), funded exclusively by Greek funds and managed by the Ministry of Shipping and Island Policy.

In this paper, we explore the application data of the TET in three dimensions: (a) the spatial distribution of the beneficiaries (residents and businesses); (b) the quantities, value and features of the freight transported to and from the islands; (c) the passenger use of TET. The exploration is spatial, with the use of ESDA (Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis) with a purpose to (i) map the geography of the beneficiaries (passengers and businesses) in relation to the size and location of the islands; and (ii) analyse the spatial distribution of the characteristics of businesses on Greek islands. These allow a critique of the TET as a transport policy for islanders and island businesses in Greece and for islands in general.

Methods and data

The Greek islands

The 114 inhabited Greek islands are in the Aegean and Ionian Seas (Figure 1, Crete is not included here) and are of varying surface areas and population sizes, from islands that are 0.33 km2 to 1630.38 km2 and are populated by 5 to 115,490 people. All the islands in the Ionian Sea and a few in the Aegean can be considered coastal islands with relatively short distances from mainland Greece. Others in the Aegean are significant distances from mainland Greece. Moreover, there are spatial clusters of islands with one or more bigger islands and smaller islands close by and local transportation networks. This results in significant variance of transport needs and situations. All islands have at least one port and bigger islands may have up to four ports. 24 islands have airports (excluding Crete). Transportation networks are mostly radial with a mainland port as the main departure/arrival hub (for most islands in the Aegean this is the port of Piraeus in the Greek capital Athens for ferries and the airport of Athens for flights). There are though spatial clusters of islands, where inter-island networks operate alongside the radial networks. Karampela et al. (2014, 2015) have analysed some of the complexities of the Aegean and spatial clusters.

In this paper, we will analyse the application of TET in the islands that are registered and eligible for it in the Aegean and the Ionian Seas. Crete is excluded from the application of the TET due to its size. Smaller islands are also excluded since for most of them the TET cannot be applied, as they have free connections for passengers and cargo from a nearby island or are considered too small and there is no fixed public transport for them.

The application of the TET in Greek islands

The official definition of the Transport Equivalent Threshold (TET) is: “the amount that would be paid for transport over the same distance by the beneficiary unit with the same composition or the beneficiary business, if it resided or had its headquarters in mainland Greece” (Government Gazette 116/A/02-07-2018, 2018). Island Cost Compensation (ICC) is “the amount paid to the beneficiary unit or enterprise and resulting from the difference of the actual transport costs of the beneficiary unit or enterprise from the Transport Equivalent Threshold.” Beneficiary Unit is “the household that, after submitting the application, has been judged to be entitled to receive ICC.”

Beneficiaries of ICC are (i) permanent residents of islands (along with some categories of civil servants such as teachers, doctors, and public health care providers when they travel to and from islands); (ii) small and medium-sized enterprises (as defined by Law 4551/2018, all businesses with less than 200 employees, practically all businesses registered on one or more islands).

The application of the TET is designed to cover (a) a percentage of passenger costs for permanent inhabitants of the islands; (b) a percentage of transport costs for goods transported to and from the islands by businesses that are registered on islands. Inhabitants and businesses have to register on an online platform and claim refunds after the trip or the transport has ended.

The calculation parameters of ICC are based (Table 1 for details) (i) on a fixed ‘Kilometer Rate’ (KR) for mainland buses, which is used in all cost calculations; (ii) the actual distance of the departure and destination port/airport in kilometres; (iii) the cost of an economy class ferry ticket for the same trip that the beneficiary has registered for; (iv) the actual ticket cost that the passengers have paid or (v) the actual cost on the quantity and type of cargo transported paid by the registered business; (vi) the distance this cargo has travelled on the basis of the freight document; and (vii) a “weighted average fare price per kilometre or tonne” calculated from the difference between the sea and the land fare for cargo. There is also a maximum annual number of tickets for passengers. The actual amount paid to passengers and businesses is complex and based on the difference between a fixed rate based on land transport and the actual price paid for the trip or transport.

The collected data from the databases offers a unique opportunity to view and analyse actual detailed transportation data, even if not all movement is included, as businesses and passengers may have chosen not to use the particular policy.

Data

The data comes from the official database for the application of the TET for the period 01/07/2018 (the beginning of the application of TET) to 12/02/2020 (roughly coinciding with the start of Covid-related restrictions). For cargo, the total number of records is 916,638, each with 29 variables, including cost, amount of TET payment, departure and arrival area (to and from island ports), and volume or number of cargoes depending on the product involved for 79 with at least one entry. All cargo is shipped to and from islands, and the original departure/destination may not be the city of the continental port, but another locality that is also recorded in the database. The businesses in the database consist of those that have registered for the TET and total 15,650 for 77 islands (including Crete) in the period 27/8/2018 – 12/2/2020. Although not all businesses on islands have registered, especially on larger islands (a detailed analysis follows), the data offers a unique glimpse of real-life transportation choices for the islands. For passengers, the data includes the number of beneficiaries, the number of tickets and the cost incurred for passengers in 77 islands in total (all variables are explained in Table 2).

Secondary data that was used for the analysis includes population, drawn from the available Hellenic Statistical Authority’s (ELSTAT) 2011 data (the most recent available for all islands at the time of publication); and the number of businesses drawn from ELSTAT’s Statistical Register of Businesses for 2016. Because the spatial reference for this number is the municipality and not the island, the number of businesses for some small islands is included in the number of the island municipality to which they belong. A ‘tourism index’ was also calculated from the ratio of the total number of tourism beds of each island (provided by ELSTAT) per inhabitant.

Data analysis

All the available TEΤ data was summarized per island for businesses, freight transport and passenger beneficiaries. We categorized islands according to their population in four categories based on Spilanis and Kizos (2015). For each size category, we compared average values using ANOVA for the number of businesses that operate and the number of businesses that participate, passengers, TET subsidy averages and the average number of trips.

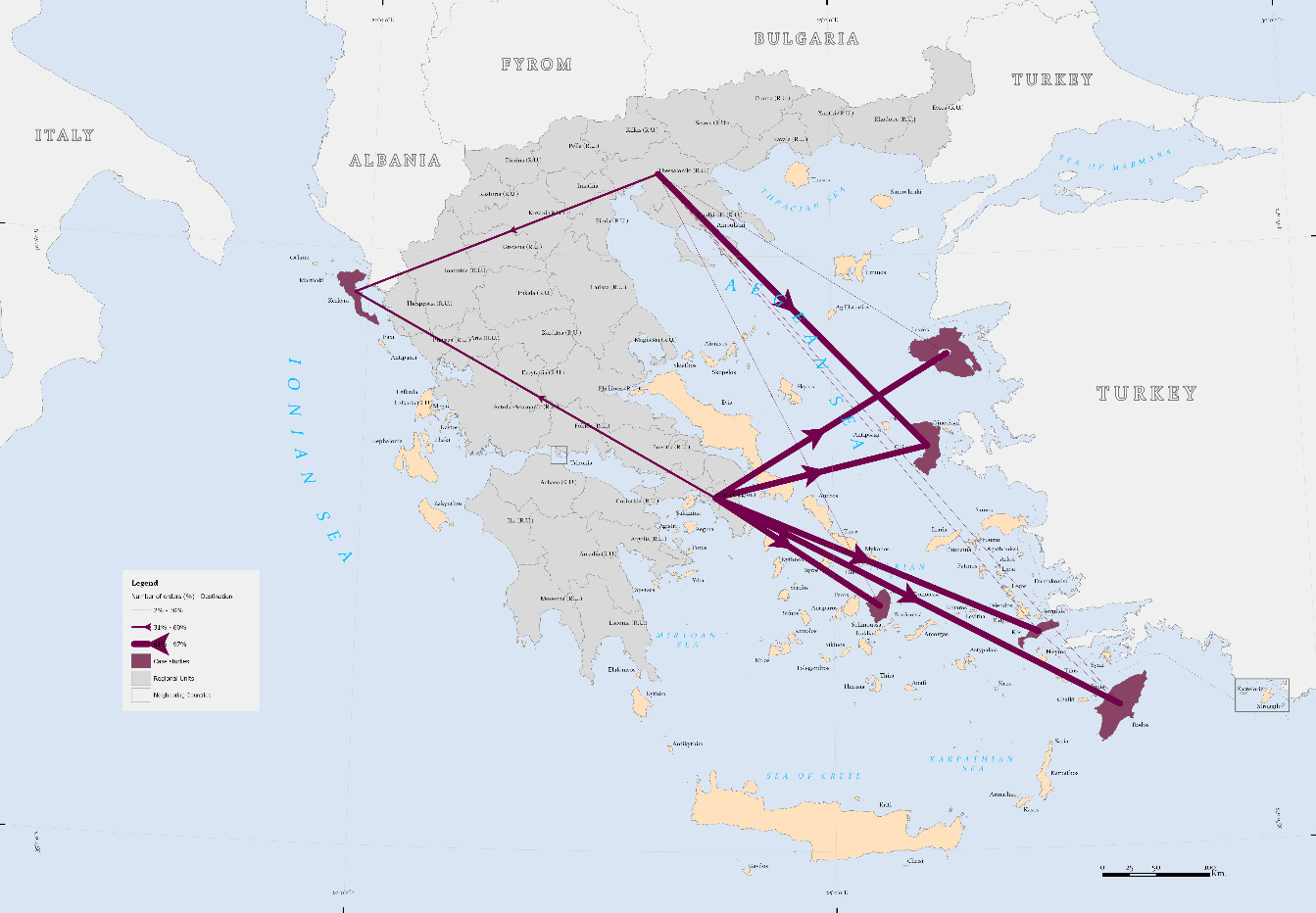

To make more sense of the freight transport data, six case studies were used for a more in-depth analysis, namely the islands Chios, Lesvos, Kerkyra, Kos, Rodos and Naxos. They are all chosen because of their size (medium to large size islands) and their geographical location: Kerkyra is a large coastal island not directly linked to Piraeus;. Naxos is a medium size island relatively close to Athens. Chios, Lesvos and Rodos are large islands, regional centres (especially Rodos) and at a significant distance from Athens. Using freight transport data, a pivot table was constructed including the number and value of orders for imports and exports for the case study islands. We then calculated the ratio of export to import orders to and from the Attica region and the percentage of exports towards other islands to examine the level of dependence on Attica. For each case study island, the percentage of total orders for imports (Figure 2) and exports (Figure 3) were mapped. Also, the freight transport flows from Attica to the islands were mapped, by using the total import orders departing from Attica (Figure 4).

Results

Businesses and TET

The ELSTAT official records show a relatively large number of businesses on the islands (Table 3 and SM Table 1), more than 125,000 or roughly 0.17 business per inhabitant. (748,939 people according to ELSTAT). This number is as expected proportional to the population size of the islands, with 44% found in the four largest islands (Lesvos leads with 17,463 businesses, followed by Kerkyra with 17,073 and Rodos with 14,122) and 44.5% in the 19 islands of the second category of population size. The number of businesses participating in the TET is around 12% of this total. The highest numbers of TET participants are still recorded on the largest islands in population terms: Rodos leads with 1,618 businesses, followed by Lesvos with 1,074 and Chios with 960. The exception here is Kerkyra where only 488 businesses are registered in the TET database, reflecting a fundamental difference between Aegean and Ionian islands. Islands in the Aegean are less coastal and linked directly to the Attica region, facing higher sea transport costs than islands in the Ionian Sea. Ionian Islands benefit less from the TET as they are linked to different nearby coastal towns for imports/exports and not to Athens, resulting in a lower percentage of sea transport cost to the total transport cost. Overall, the percentage of businesses registered for the TET is inverse with population size and increases for smaller islands, for which as many as 43% of the total number of businesses have registered, compared to much lower percentages for largest islands.

This finding of the growing number of participating businesses with decreasing population size is unsurprising, as in bigger islands, less businesses are directly transporting their own business goods, but prefer to use specialized intermediaries. Another explanation can be the tourism of the islands. Islands with high tourism activity may have tourism businesses that do not transport products. Businesses’ main activity code average distribution points out that almost 40% of the island businesses have tourism activities and 41% wholesale and retail trade activities. The overall distribution of the number of businesses participating in TET though is again proportional to the size of the islands (Table 3, column 4), except for the four very big islands, for which the many of their businesses do not have to transport their goods (e.g. on Lesvos 6% of the business are registered, on Rodos 11% and on Chios 14%). The ratio of participating businesses per total number of businesses is higher on islands such as Kimolos (57%), Sifnos (53%), Milos, Anafi, Ios and Folegandros, revealing a pattern for small and medium size islands in the Cyclades islands.

Businesses are also differentiated according to their main activity code, and their variety is proportional to the island size (Pearson’s rho= 0.85, p< 0.05). The relationship between business main activity variety and number of registered businesses does not differ significantly between the islands. Perhaps lower varieties were expected explaining the existence of many transport businesses using TET, but there are many different business types using TET.

The turnover average of participating businesses, as well as the subsidy average, are proportional to the island population as expected, but the second population category has almost half of the total TET turnover, due again to the bigger needs of their business to transport at least some of the goods themselves, compared to those in the biggest islands. The fewer and bigger businesses in bigger islands receive on average more money per business (approximately €750, Table 3), as they generally carry more cargo (in terms of both quantity and value), compared to businesses in smaller islands that on average receive almost one-third of this sum per business.

Transportation in the case studies

The findings for transportation in the case study islands reveal the huge difference between the number and value of transports that import products to the islands and the number of transports that export products from them (Table 4). For the medium to big size case study islands, the average number of transports out is only 4% of the transports in, while the value of transports out compared to transports in is slightly higher at 7%. The differences between the islands reflect their production differences. Islands such as Lesvos, Chios and Naxos produce and export agricultural products (cheese, ouzo and olive oil for Lesvos, Mastic and oranges for Chios, cheese and potatoes for Naxos) and therefore record higher export to import ratios. For islands that rely almost exclusively on a tourism monoculture, such as Kos and Kerkyra, the ratios are significantly lower. Rodos lies between these two groups (Table 4). But even for islands that export raw and processed products, the ratio is very low. The ratios of smaller islands are below the average for the case study islands, and for many of them, exports are zero (Supplementary Material (SM) Table 2), compared to the value of exports from Lesvos, which reach nearly 30%. These values are only for transported goods that are recorded in the TET databases and not all transported goods but nevertheless confirm the very real degree of dependence on imports for all these islands.

The departure points of imports reveal the dependence on the metropolitan area of Athens, especially for islands in the Aegean. Except for Lesvos, which is linked to ports in North Greece as well, all other Aegean Islands import as much as 90% of their total cargo from Athens (Table 4, Figures 2 and 3). These results have to be interpreted by keeping in mind the actual transportation options of businesses. While almost all Aegean islands are connected to the hub of Athens via the port of Piraeus, very few are directly linked to other continental destinations. Kerkyra, which is a coastal island in the Ionian Sea (Figure 2) is linked only to nearby Igoumenitsa and therefore depends less on Athens, but even so, almost half of all cargo departs from there.

The main destination of the exports for these big islands is also the metropolitan area of Athens to a large degree, but lower than the average of all 76 islands (74%, Table 4, Figure 2). Here the role of some of these islands as local and regional centres for redistributions of imports is confirmed. The most notable example is that of Rodos, which redistributes cargo to nearby small islands, but also Naxos, Kos and Kerkyra. The location of the islands explains some of the differences, as for example the businesses of Kerkyra use TET to a lesser degree due to the proximity to the coast and low shipping costs. Chios on the other hand exports more than the other case study islands to the Attica region, compared to Lesvos, for which its location at relatively the same distance from North Greece leads to bigger shares exported there than other islands.

Passengers

The database of TET for passengers shows that roughly half of the inhabitants have been registered in the system. This percentage is significantly larger (65%) for small islands (Table 5 and SM Table 3). This overall low percentage of registered inhabitants probably reflects two different issues: that a proportion of the inhabitants of the islands do not travel frequently out of their islands (probably elderly people and/or people that have spent their whole lives on the islands) and therefore have not registered to the TET. Also, families register their members as different users and therefore for those that have not registered at all, the rest of the family members are not registered. There are some islands though that are upper outliers in registration numbers, such as Sifnos, (in the 750-5,000 inhabitants category), where 99% of the inhabitants are registered. Many other small islands in the Cyclades record high percentages of registration as well, unlike islands in the Ionian Sea of the same size, probably due to location of the islands and cost issues of the trips.

The overall number of trips is related to the size of the islands, but the average number of trips per registered user reveals that inhabitants of bigger islands travel less often on average than those of smaller and very small ones (Table 5), even though more people are registered for the TET subsidy in bigger ones on average than those in very small ones.

Discussion

In this paper we present the first results of the implementation of a policy measure that allows a first glimpse into actual transport practices for businesses and inhabitants of islands. This glimpse is very valuable, as it reveals the differentiation of the practices of inhabitants of the islands and the day-to-day import and export transports for businesses operating on the islands. Arguably, the data recorded in the TET databases does not cover the complete range of people and businesses and trips, and we do not know the reasons behind participation rates in the TET. But such a glimpse at this level of detail is available for the first time for this range of islands and businesses in Greece.

Concerning the number and type of businesses that have registered in the TET, almost 80% of the participating businesses are in the first two size categories of islands, which reflects the unequal economies of Greek islands and also inter-island competition (see also Baldacchino & Ferreira, 2013) as well as the high disparities of the policy tools and frameworks with which businesses must operate. The challenge of reaching and catering to the needs of the smaller businesses of smaller islands is a major one (Jugović et al., 2021; Makkonen et al., 2013). Another finding is the growing number of participating businesses with decreasing population size. This is unsurprising, as in bigger islands, fewer businesses are transporting their own or other businesses’ goods and most deal with inter-island orders for some or the total of their supplies. This is not the case in smaller islands, where almost all businesses have to import their supplies off island. This is reflected in the analysis of their Main Activity Code Numbers, which shows the predominance of tourism or wholesale and retail. This is an important finding from a policy point of view, as it highlights again the different needs of businesses even within a relatively homogenous area such as the Greek archipelagos. Similar research in international settings (Pounder & Gopal, 2021) points to contextual issues such as entrepreneurial support (besides prosperity and wealth) as important. The question of whether and how the application of the TET should take into account these different needs of business in smaller islands remains an important one.

The analysis highlighted the dependence of islands on the mainland with a radial system with Attica at its centre (see also Odchimar & Hanaoka, 2017 for a similar case in the Philippines). Significant differences are evident between the Aegean and Ionian Seas related to the location and geography of the islands, with coastal islands in the Ionian Sea being linked to mainland ports rather than to one another. On the contrary, in the Aegean, the existence of smaller archipelagos within the main archipelago emerges (Karampela et al., 2015; Papadaskalopoulos et al., 2015). A notable example is Rodos, which functions as a local centre, highlighted by the destination of export cargo towards other islands, with hubs and satellite smaller islands. Naxos too confirms the findings of Karampela et al. (2015; see also Pimentel et al., 2022 for the Azores). This finding seems to reaffirm the need to move away from a radial system to a more ‘hub-and-spoke’ system of transport (Papadaskalopoulos et al., 2015) and to take advantage of regional and local centres, in a policy that could supplement the TET. This is an issue that many archipelagos face (e.g. Makkonen et al., 2013; Pimentel et al., 2022; Sugiyanto et al., 2015).

Concerning imports and exports, the TET records reveal a very high degree of dependence on imports. Although typically island businesses express the view that transport costs hinder entrepreneurship and slow new businesses (Angelis, 1994; Katsounis et al., 2019), what remains to be seen is if the long-term application of the TET will encourage and support exports from islands, either from existing businesses or from new ones. It may be the case that this high degree of dependence reflects a structural feature of small island economies that go beyond mere transport costs and refer to other types of disadvantages that small island economies face, such as lack of economies of scale, lack of access to trained personnel and business services, among others (Hurley, 2018; Katsounis et al., 2019; Lekakou et al., 2021). So far, it seems that the application of the TET merely provides incentives to businesses that already exported from the islands. Of course, a policy measure such as the TET could not be used to address all the difficulties and disadvantages that smaller island economies and businesses in such islands face, and it must be used within a more integrated approach.

Concerning the users (passengers) and their trips, Karampela et al. (2015) and Spilanis et al. (2012) have suggested that people who live on bigger islands have less reasons in principle to travel from their island, and this is supported by the TET data. Karampela et al. (2015) did not have data for inhabitants’ trips, so they separated tourist trips from those of the residents by using the trips in February as an indication of the monthly travel rate of inhabitants for a few Greek islands. Their findings indicate lower resident trip rates for big islands such as Rodos (around 2 per year/inhabitant), compared to 5 times this rate for smaller nearby islands. The on-island availability of a greater variety of services reduces the number of off-island trips that are absolutely necessary for e.g. medical exams of various kinds that are not available on site, or their quality on the island is not perceived as good by some of the inhabitants. Other popular reasons according to our experience are court attendance, examinations for foreign language degrees, studying, sports, etc. ‘Non-vital’ reasons for travel must also be added, such as social occasions, shopping, vacations, meeting family, etc. It seems that island residents plan their trips off their islands on a necessity and cost basis. Having family and friends that can accommodate short stays in the destination is another factor that eases the decision to travel. This is an issue understudied so far according to our knowledge. Although it may not be appear as immediately related to measures such as TET, the need to travel more frequently from the island of residence is one of the aspects that shape islandness/insularity (Baldacchino & Starc, 2021). This has not been considered in the application of the TET so far which seems to favour residents of bigger islands that may choose to travel to access a service and use the TET, while residents of smaller islands have no choice but to travel if they wish to access the same service.

Conclusion

The TET approach is one of the possible approaches that can and have been used to address transport and travel issues faced by people and businesses on islands. It does provide financial subsidies to both people and businesses and therefore cannot be dismissed as a viable policy option for islands and archipelagos. On the other hand, a few negative issues seem to emerge, some of which appear to be related to its principles and other to the application adopted in Greece. Concerning the TET principles, it can be argued that the very idea of equating costs of air and sea travel with land travel seems problematic in principle. Even if some type of ‘basic level of service’ is defined and then used to make calculations, some of the examples presented here reveal its arbitrariness: the ‘basic level of service’ is inevitably an administrative definition (in Greece based on bus cost on land per km) and which is used for all necessary calculations. Various costs involved, the different competition regimes in sea/air transport between islands that have busy lines and real competitions and others that operate at marginal gain or loss and are subsidized (as is the case for many lines in the Aegean), increase the inherent complexity so much that a comprehensive application of the principle is almost impossible for a few islands and transportation means.

Another issue is related to the overall objective of the TET. It can indeed provide some assistance to businesses that export and import goods, but it cannot be considered as a tool for developing new businesses or new approaches to transport on the islands. It seems on the contrary that it helps existing businesses and, in this sense, it may aid the monopolies and monopsonies that are often found in small and isolated markets such as those of islands. A more integrated approach that combines the application of TET with other policy approaches is needed, which can help new businesses and approaches to transport, adapted to islands’ needs.

What also seems to be an issue of a policy measure such as the TET is how to incorporate the different needs of businesses even within a relatively homogenous area and especially in smaller islands that have to face the competition from businesses on bigger islands. This is related also to how a policy such as the TET can be combined with the need to change the overall transport mode towards a more ‘hub-and-spoke’ system. Finally, the heightened need for travel on the part of residents of smaller islands must also be considered.

The application of the TET in Greece highlights some of these issues. It seems to be adjusted to the specific archipelagic characteristics of Greek islands, but at the same time it does not consider the size of islands and its effect on residents’ and businesses’ available choices and practices and appears to favour bigger islands. Moreover, as it is applied, the major beneficiaries are transport companies that ship in and out goods for other businesses. Although nominally the recipients of the subsidy are not transport companies, the real benefit is for them, as they price their services accordingly. This has not made a real difference to small businesses, which are the ones that really need the assistance of the TET, that rely on transport monopolies to price their exports and imports. The usual practice is to price per truck (if a business can fill a whole truck, discounts of up to 50% are offered), per palette (for a whole palette) and per place in a palette (where other cargo is also placed). This shows the limits to applying a horizontal measure to diverse islands and transport settings, although administrative simplicity and transparency is a big plus for the application of the TET in Greece.

Overall, the TET is a policy option for islands, as it can provide assistance to people and business that live and operate on them. Comparisons with application approaches in other settings and the maturation of its application in Greece can provide a better and more effective application in the future.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support of the General Secretariat of the Aegean & Island Policy (GSAIP), via the project ‘Evaluation, redesign and monitoring of measures to reduce intra-regional disparities, containment and cohesion of the island population’. The views expressed in this paper are of the authors and not necessarily reflect those of the GSAIP.