The stately palm was bowed and bent,

Asokas from the ground were rent,

And towering sáls and light bamboos

And trees with flowers of varied hues,

With loveliest creepers wreathed and crowned,

Shook, reeled, and fell upon the ground.

With mighty power piles of stone

And seated hills were overthrown:

And ocean with a roar and swell

Heaved wildy when the mountains fell.

Then the great bridge of wondrous strength

Was built, a hundred leagues in length.

Rocks huge as autumn—clouds bound fast

With cordage from the shore were cast,

And fragments of each riven hill,

And trees whose flowers adorned them still.

Wild was the tumult, loud the din

As ponderous rocks went thundering in.

Ere set of sun, so toiled each crew,

Ten leagues and four the structure grew

The labours of the second day

Gave twenty more of ready way,

And on the fifth, when sank the sun,

The whole stupendous work was done(The Ramayan of Valmiki, translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith, Book 6, Canto 22)

Introduction

In May 1967, an article in Akashvani (All India Radio) plugged the Sethusamudram Shipping Canal Project as ‘The Suez [Canal] of Asia’ (Natarajan, 1967, p. 1). Planned as far back as 1955 (if we exclude colonial-era proposals), Sethusamudram is a proposed marine channel between India and Sri Lanka across Adam’s Bridge; it is also the name of the sea-stretch between India and Sri Lanka.

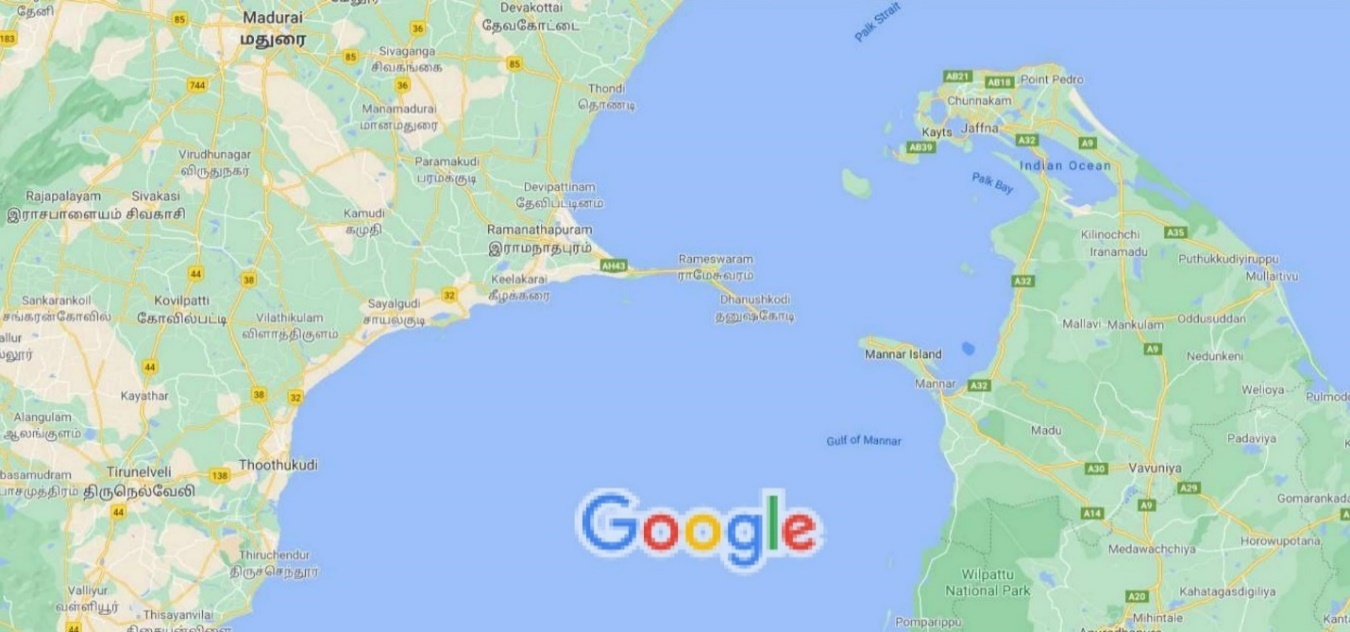

Adam’s Bridge is an approximately 48 kilometre-long isthmus of shifting shoals on the shallow stretch of the Indian Ocean between India’s Pamban Island and Sri Lanka’s Thalaimannar (Figure 1), known as Palk Strait (named after the eighteenth-century Governor of Madras, Robert Palk). The exceptional tombolo-like geology of the ‘bridge’ is famous for religious, political and economic controversies.

Also known as Ram Setu, after the Hindu epic Ramayana (written by sage Valmiki, circa 1000-500 BC), Adam’s Bridge is believed to have been built by an army of monkeys led by Hanuman on behalf of the avatar Lord Ram. The ‘bridge’ was meant to facilitate Ram’s march from India to Sri Lanka, where he would defeat the Asura King Ravana (also described as a Vedic scholar in Dravidian versions) to rescue Sita (Ram’s wife) from house-arrest in Ashoka Garden inside Ravana’s palace. In Abrahamic mythology, Adam’s Bridge is believed to be Adam’s footprints from the time of his expulsion from Paradise, his ascension on Earth in Sri Lanka and his crossing the ocean into India.

Besides its mythological and geopolitical importance, Adam’s Bridge is a natural wonder and an epistemological problem for island studies, not least because it complicates the colonizer/colonized binary. At the heart of my study are questions of enchantment and matrices of power that determine the epistemes to reproduce the power to enchant or disenchant.

The Sethusamudram Project, whose construction was halted by a 2013 judgment of the Supreme Court of India due to religious sensitivity, was proposed as a navigable pass for large cargo ships across Adam’s Bridge. Since the first plans of coastal development of the region were floated in 1955, there has been great ambiguity on whether dredging the tombolo would destroy the segment of the land-water assemblage revered as Ram Setu. The Mudaliar Committee, appointed in 1955 to study the feasibility of Sethusamudram, reported that Adam’s Bridge was highly “unsuitable” for dredging (Mudaliar et al., 1957, p. 5). The Committee proposed dredging around Rameshwaram or Pamban Pass (Pamban Beach or the site of the Pamban Bridge; Figure 1). Though plans for dredging around Pamban Pass have been floated since 1860, colonial surveyors too disapproved of dredging Adam’s Bridge due to its extraordinary sand shifts and reef formations. Further, colonial geological records paradoxically reveal a benevolent interpretation of Ram Setu’s mythology by British historians and scientists. This raises the question of the agency of that interpretation, and the problem of the insider/outsider binary while determining the legal, environmental, political, geological and sacred history of Adam’s Bridge.

The increasingly solidifying perception that the Indian Ocean is “the heart of geopolitics” stimulates the need for India to promote trade and dialogue with islands in the Western Indian Ocean, like Seychelles, Madagascar and Comoros, besides Sri Lanka (De et al., 2020, pp. 1, 9). In keeping with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, if an international navigable pass or canal—like Sethusamudram—is made open to traffic, then international ships (including American, Russian, and Chinese warships) will have the right to innocent passage (Stein, 2018, pp. 3, 8–9), unless India and Sri Lanka chart out a treaty governing passage between the two states. This makes Sethusamudram a strategic flashpoint.

On the other hand, Adam’s Bridge’s colonial history, seen in the light of the Hindutva mobilization to classify it as a national heritage monument, recasts the Sethusamudram as a strategic internal conflict for the Indian state, that can and does polarize Indian citizens on the issue of the region’s sacred geography. The divide between believers in the sacred mythography and nonbelievers entails a default polarity between those who believe Adam’s Bridge to be manmade bridge over the sea and others who see it as a natural formation. To accord the status of a bridge to Adam’s Bridge/Ram Setu would mean classifying it as a group of artificially constructed islands or an archipelago, whose sacrality is a default signifier of small landmasses surrounded by water as relics of a bridge. Calling it a natural formation implies considering it as a de facto barrier to oceanic connectivity between the islands of Pamban and Mannar.

This religious and epistemic conundrum around Adam’s Bridge is, in fact, a colonial-era legacy. Without understanding how the colonial state saw Adam’s Bridge, we may wrongly infer that today’s nationalist assertions of its sacred mythography stem from an anticolonial praxis to restore a politics of enchantment within Indian modernity. Ironically, the British colonial state adopted epistemes or modes of knowing Adam’s Bridge that were ostensibly compatible with pre-Western forms of enchantment. This is particularly important considering that nationalist voices, largely represented by the right-wing BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party), RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) and the Sangh Parivar, in general, and liberal voices representing the Congress (Indian National Congress), or regional political voices such the DMK (Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam) and AIADMK (All Indian Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam), have dated the origins of the Sethusamudram to the colonial era, erroneously prolonging the implication that the British government aided plans of demolishing Adam’s Bridge.

Enchantment and islandness

Fortuitously, Adam’s Bridge’s historiography recalls studies in the history of ancient and imperial Chinese sacred islands, which were traditionally seen as homes of gods and dragon kings, under Taoist and Buddhist influences, respectively (Luo & Grydehøj, 2017). Like in China, nineteenth-century colonial India saw the parallel evolution of sacred traditions of Pamban Island with the abject status of the Andaman Cellular prison, a little over 1,200 miles away. Referred to as kaalapani (or ‘dark waters’), in Indian parlance, the Cellular Jail was the anchor of a convict colony that the British government established in the Andaman Islands. Pamban was seen by both Hindus and the colonial government as a sacred shrine of Lord Shiva where pilgrims came to seek an enlightened life. But Port Blair’s Cellular Jail (established in 1906) became a site of quarantining the seditious and delinquent subjects of Empire, often for life. The evolution of the sacred and political contexts of Pamban and Andaman Islands, respectively, under the British colonial regime is well within the ambit of what is understood as ‘decolonial island studies’ (Nadarajah & Grydehøj, 2016)—both in terms of defying colonial epistemes and charting out a ‘decolonial option’ following Walter Mignolo’s (2011, p. xxvii) vision of “delinking from coloniality, or the colonial matrix of power.” But for any study of the colonial evolutions of islands and islandness, it is crucial to interrogate the coloniality of epistemes in which knowledge about individual islands is produced, disseminated and reproduced.

Adam’s Bridge’s fabulous and/or sacred geography remarkably informed the colonial imagination of India. By and large, the colonial state—despite its policy of marginalizing Indian traditions and languages since Macaulay’s infamous Minute on Education (1835)—showed a stance of compatibilism or, at worst, non-coercive scientism towards Pamban’s sacred mythography. Luo and Grydehøj (2017, p. 26) have argued that “inattentiveness to non-Western ways of seeing, thinking about, and practicing islandness perpetuates processes of domination and marginalization … [as] fascination with islands is specifically not an innovation that the West introduced to the rest of the world, yet this is scarcely reflected in many of the most important scholarly efforts to theorise islandness.” But the colonial state’s fascination with Adam’s Bridge was not wholly Western or even colonial. The fact that it was jointly influenced by Orientalist and non-Western epistemes of seeing and thinking about island geographies complicates the trialectic between colonial, anticolonial and decolonial.

I see Adam’s Bridge’s complex historiography in line with Sumathi Ramaswamy’s (2004) critique of hyper-scientific modernity and disenchantment. Her book, The lost land of Lemuria underscores “the ontological challenges of decolonial island studies, from mythic fabulations to the periphery of national imaginaries, as many island societies have found themselves in the post-independence phase” (Gómez-Barris & Joseph, 2019, p. 2). Ramaswamy’s (2004, p. 15) “hegemony of the real and the visible” is deeply appropriate with regard to the abject status of:

those place-making imaginations that are not necessarily rooted in disciplinary geography’s normative planetary consciousness that transformed the globe into a disenchanted place over the course of the imperial nineteenth century, that disavowed imagination in favor of empirical reason, and that consolidated (the metropolitan) man as the all-knowing subject and master of all he surveyed … they remind me … that our earth can continue to be an enchanted realm even after being colonized by modern science (Ramaswamy, 2004, p. 15).

Like Ramaswamy (2004), mine is an epistemic concern for discourses of enchantment that are thwarted by modernity or instrumentalized by promissory antagonists to modernity. Reflecting on Ramaswamy’s study of nineteenth-century occultist and theosophical imaginations of Lemuria, I believe that, ultimately, empiricism and material science are insufficient to rationalize or reify the sacred mythography of Ram Setu. What holds the key to reconcile mythical sacredness with the everyday secular (in the Indian context) is what Ramaswamy (2004, p. 94) has called a transparent enchantment that is “liberated from this constraint of grounding their claims in evidence that is subject to measurement, verification, and the other mundane demands of legitimate scientific methodologies.” Unlike late-nineteenth-century occultists like Helena Blavatksy, I do not mean to re-divinize a secular society “from which god had been dismissed by the material sciences” (Ramaswamy, 2004, p. 94). I may end up peripherally restoring “the lost unity between spirit and matter, and of the lost nexus between religion and science” (Ramaswamy, 2004, p. 94) that theosophy and occultism sought, for instance. For, as Ramaswamy (2004, p. 139) would have it, “the ocean’s mysteries could still hold one in thrall.” But fundamentally my objective is to demonstrate that the scientific gaze, even the gaze of colonial science that has been implicated by nationalists and liberals, was and remains capable of accommodating epistemic plurality in a symbiotic coexistence of science, spirituality, modernity and enchantment.

En passant, I shall try to answer a vital question—one that Ramaswamy (2004, p. 166), too, asks in Lemuria’s context: “How does one realistically describe a fabulous antediluvial landscape that is no longer available to empirical knowledge, if it ever it was?” It is still poignant to raise Ramaswamy’s (2004, p. 223) question, eighteen years after it was first posed, that is, how to reclaim enchantment in “postcolonial India, where one’s credentials as modern—and hence, as rational and as civilized—are established by adhering to the parameters and protocols of the new sciences and disenchanted knowledge-formations that have been ushered in from the metropole.” Historicizing Adam’s Bridge, then, is also a refusal to cave in to “the pressure to think realistically and disenchantedly in the face of the widespread modernist condemnation of the fabulous and fantastic native mind” (Ramaswamy, 2004, p. 226). Nonetheless, this refusal is emphatically not an uncritical acceptance of majoritarian exploitation of our elemental desires for enchantment or enchantment as an intangible utility in electoral politics. Rather, the kind of enchantment and epistemic plurality that have accompanied historical discourses around Adam’s Bridge have become casualties in the pursuit of secularist and nationalist ideologies, particularly in and around electoral contexts.

The problem of Adam’s Bridge also correlates to a mainland-island dichotomy or what is better recognized in the phrase “centre-periphery relations” that, in turn, shape political cultures of islands and their sovereign states (Grydehøj, 2016). Thinking about Adam’s Bridge is to encounter what Jonathan Pugh (2013) recognizes as the metamorphic power of island movements. Although Pugh’s use of ‘movement’ suggests cultural and political transformations, the sandbars of Adam’s Bridge are literally in a movement capable of destabilizing grand mythological, geological and nationalistic narratives. Seen in the light of island studies as a decolonial methodology (Grydehøj, 2017; Nadarajah & Grydehøj, 2016), a decolonial narrative of Adam’s Bridge is not necessarily anticolonial, since British colonial and Indian nationalistic narratives coalesce and cohabit instead of being in conflict. Adam Grydehøj’s (2018, p. 8) answer to the question of whose voice we must hear in adapting a decolonial praxis is pertinent here: “When considering island and Indigenous issues, it is, to my mind, no more reasonable to seek to exclude all non-island and non-Indigenous voices than it would be to seek to exclude all island and Indigenous voices.” This recalls Godfrey Baldacchino’s (2008, p. 50) notion of the importance of ‘outsiders’ to island histories: “Were ‘outsiders’ not involved in the (problematic) task of commenting on and about islands, most of us would be facing the dire prospects of an absent script. The inclusion of the ‘islander-as-subject’/indigenous point of view cannot be ignored; but nor can it be construed as exclusive.”

It is appropriate to add Baldacchino’s (2002) caution about “homogenizing discourses” that small islands fall prey to, due to mainland or continental projections of a hegemonic identity. Given that, the overwhelming importance of the structure in Indic national and civilizational self-determination suggests that we cannot confine critical thinking on the so-called limestone-shoal-bridge to geographical features, alone. Reiterating Baldacchino’s (2004, p. 280) question on the coming of age of island studies, can our thinking on Adam’s Bridge be reduced to an “obsession with only one type of island—the literal, physical type—fuelled by a jaundiced, mainland-driven impression”? John R. Gillis’ (2007, p. 286) point on how small islands “loom largest in contemporary consciousness” sits wonderfully in this context. Adam’s Bridge manifests what Gillis (2007, p. 286) calls “our most intense desires and the locus of our greatest fears about environmental degradation, even species extinction. We feel extraordinarily free there, but also trapped … still a part of that mythical geography we can never do without.” Gillis’ (2007, p. 286) taxonomy of islands as those sites we revisit “on a seasonal basis, hold them hostage to our hopes and fears, rarely allowing them to represent themselves to the world at large,” somewhat inadvertently, is in dialogue with the Adam’s Bridge narrative, especially given how the matter has been politicized according to India’s electoral seasons.

Politicizing Adam’s Bridge

Among its several controversies, Adam’s Bridge is susceptible to what has been identified as the “discourse of a ‘China threat’ to justify neocolonial entrenchment in the form of greater Western militarization and economic dominance” (Grydehøj et al., 2021). But the ‘China threat’ has been sounded not by Western or erstwhile colonial powers but Indian regional powers (prominently, Chief Minister MK Stalin-led DMK in Tamil Nadu) to persuade the Indian government for greater development around Pamban Island and Sri Lanka, facilitated by the construction of the Sethusamudram (Simhan, 2021). Meanwhile, Tamil fishermen’s groups have opposed Sethusamudram, citing environmental concerns that may adversely affect their livelihoods, regional geology and geography if Adam’s Bridge is demolished (Nagpal, 2007; Subramanian, 2005; Fishermen up in Arms against Promises of AIADMK, DMK, 2021). There is, therefore, an epistemic ‘power-geometry’ at play, to use Doreen Massey’s (2009, pp. 22–24) phrase, which has led to plural contradictions and dissensions around the canal project.

The fate of Adam’s Bridge affects the formal geography of India. New cartographic markers can now be found denoting sites of Hindu and Islamic sacredness on Google imagery of Adam’s Bridge (Figure 2). Besides, after the Ayodhya verdict of 2019 and the commencement of the building of the Ram Temple at Ayodhya, Ram Setu is likely to become another electoral issue.

In February 2021, A. Ramasamy, former Vice-Chancellor of Alagappa University (Karaikudi) and president of Dravidian Historical Research Centre, filed a controversial petition at the Supreme Court with the help of advocates M. Munusamy and A. Lakshminarayanan, to challenge the myth of Ram Setu. He cited Johnnes Walther’s (1890) ‘Report of a journey through India in the winter of 1888-89’, published in Records of the Geological Survey of India. The petition argued that Walther’s research was not compelled by any “political pressure”, and that the “national [Tamil] poet” Subramania Bharati saw the Ramayana as mythological (Ram Setu Not an Ancient Monument, 2021). But Ramasamy evaded the fact that Bharati, after reading Shelley, Goethe and Victor Hugo, had remarked that no “modern vernacular of Europe can boast works like … Ramayana of Kamban” (a Tamil version written around the twelfth century on the model of Valmiki’s Ramayana), among other Indian literary gems (Bharati, 1937, p. 62; Ramaswamy, 1997, p. 54). Besides, unlike Ramasamy’s representation, Walther (1890, p. 115) found Adam’s Bridge to be “of equal interest to the lover of old Indian myths, as to the Geologist and the student of geographical distribution of animals.” If we read Walther directly, we find an acknowledgment of epistemic plurality in seeing the islandic terrain. For Ramasamy, Walther was disenchanted. However, in Walther’s (1890, p. 116) own words, “Adam’s Bridge existed once, a long time ago” and that “a land connection between India and Ceylon existed twice, and has twice been interrupted, and that more than one migration of the fauna from India to Ceylon could have taken place”—thence entangled with modes of enchantment, whether spiritual, secular or scientific.

Ramasamy’s claim was countered politically by BJP-leaning Hindutva platforms, such as Hindu Post, that cast moral aspersions on the plaintiff’s intention: “when the study he [Ramasamy] quotes was conducted in the time of British Raj which had anything but scorn for the native Bharatiya” (MahaKrishnan, 2021). The Hindu Munnani (a Hindutva organization) has also tried to paint Ramasamy as a stooge of the DMK (MahaKrishnan, 2021). As suggested earlier, the case is more complex than a political battle between a secular DMK citing colonial-era research and a nationalist BJP rejecting them on anticolonial grounds. Ramasamy’s pro-Sethusamudram petition was factually inaccurate. Meanwhile, right-wing arguments for Ram Setu’s recognition as national heritage are not without epistemic flaws either.

On December 2, 2015, BJP Lok Sabha member Keshav Prasad Maurya raised the Sethusamudram issue in Parliament. He claimed that the previous UPA (United Progressive Alliance, formed as a coalition between Congress and its allies) government had made a “deal with foreign forces” to dredge Adam’s Bridge despite knowing of the presence of massive lithium deposits [sic]—(he probably meant thorium)—at the site (Maurya, 2015). Earlier, Vinayak Kale, a coordinator of the Rameshwaram Ram Setu Raksha Manch (a Sangh activist body) had alleged that a “foreign hand” wanted the demolition of Ram Setu knowing that the site’s “deposits of around 3,60,000 tonnes of thorium” would sink in the ocean floor if the dredging went ahead (Foreign Hand behind Ram Setu Demolition, 2008). Apparently, the thorium deposits “can produce electricity for India for the next 400 years, at least, even if the annual consumption is four lakh watts” (Foreign Hand behind Ram Setu Demolition, 2008).

In such rhetorical rejoinders, ‘foreign’ hand implies the growing economic strength of China or the influence of the United States of America and United Nations in India’s International Waters policy. But foreign has other implications, too, in the context of Adam’s Bridge.

On July 1, 1982, V. Sundaram, Chairman of Tuticorin Port Trust, wrote a fractious letter to the chief of the Lakshminarayanan Committee that was appointed by the government of India for evaluating the Sethusamudram Project. Inter alia, Sundaram expressed concern over “the surreptitious subterranean efforts being made by the Catholic Church in Tamil Nadu to influence the Government of India to somehow destroy the Ramar Sethu Bridge just in order to give a death blow to an ancient symbol of Hindu religion” (qtd. in Swamy, 2008, p. 218). BJP leader and scholar Subramanian Swamy (2008, p. 20), who reproduced the letter in his book Rama Setu, is a vociferous critic of “the United Progressive Alliance Chairperson Ms. Sonia Gandhi,” whom he calls “a devout Catholic” and “compliant to cues from the Vatican” insofar as to cause the “debasement of a Hindu icon” by a “wanton desire to destruct the Rama Setu.” In underscoring the fallibilities of “Indian tutees in an Anglo-Indian educational system” bred on works of East India Company historians James Mill and Charles Grant (Swamy, 2008, pp. 37–38), historical notions like the Aryan invasion theory as a “figment of imagination” of British imperialists (Swamy, 2008, p. 39), the “jealousy” and “consternation” of “British trained historians” (Swamy, 2008, p. 40), and attributing the name ‘Adam’s Bridge’ to the self-serving agendas of “toadies of British imperialists” (Swamy, 2008, p. 171), Swamy has tried to create the impression that the British colonial regime was fundamentally antithetical to the sacred mythography of Ram Setu/Adam’s Bridge.

Swamy, who is a highly regarded and controversial political thinker, is echoed by many nationalists in his stand on Ram Setu. Take the view of Ratan Sharda, an RSS ideologue. Questioning the government’s plan to “steamroll an issue like Ram Setu … very close to Hindu’s hearts,” Sharda (2018, p. 69) reckons that it is the result of “regurgitating the information created by colonial mindset.” M.D. Nalapat (2019), another right-leaning intellectual, has argued in a popular article for the recognition of the sacred Hindu history of Adam’s Bridge, claiming that “India’s history as dictated by the British has largely continued its sway over school and college curricula, and thereby into mindsets,” to delegitimize India’s Vedic cultural heritage. Arguments like Nalapat’s (2019)—that the British “colonial empire” served to “reduce the imprint of both the Vedic as well as the Mughal periods” in Indian history—seek to unite nationalism and anticolonialism. And, since “the post-1947 leadership of the country adopted, often without adaptation, an overwhelming proportion of colonial constructs and practices, it was no surprise that India’s history as dictated by the British has largely continued its sway over school and college curricula, and thereby into mindsets” (Nalapat, 2019). Elsewhere, the perils of “colonial mindset” are juxtaposed against the ostensible largesse of ‘American’ science. Writing on the issue of Ram Setu’s historicity, Shiban Khaibri (2017) asks, “why have Americans to clarify our controversies like the one under reference? Why has National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to remove our doubts which otherwise could be done by us?” Because, he answers, “the post-independence era virtually still appears to wear colonial mindset” (Khaibri, 2017). The argument recapitulates an old tirade, by Satya Pal Singh (2008), titled ‘Proving the historicity of Ram’, where, however, American scholars were not celebrated but decried. Singh cited the book Invading the Sacred, edited by Krishna Ramaswamy, Antonio de Nicolas, and Aditi Banerjee (2007), to argue how “unlike in India, the academic study of religion is an important undertaking for intellectuals in America and a few hundred scholars study Hinduism and other Indian religions” (Singh, 2008). Arguably, mistranslations and misinterpretations of “Indian culture and religion … in line with the colonial and missionary caricature of India” had been propagated, which the book in question sought to override. However, Singh (2008) also asserted that “the scientific interpretation of the photographs of the remains of Adam’s Bridge (Ram Setu) taken by NASA’s Gemini-11 spacecraft in 2002, reveals that this ancient bridge linking India to Sri Lanka was manmade, and it was dated to be at least 1.75 million years old.” Several right-wing arguments thus point to a nexus of anticolonial nationalist ideology (that denounced ‘colonial’ epistemes) with ‘American’ science.

Evidently, the British colonial regime or its so-called relics are the primary significations in many articulations of the ‘foreign’ hand. Christophe Jaffrelot’s (2008) article on the synthetic outrage of Hindutva activists over feared damage to Ram Setu suggests that this scheme of otherization—epistemic polarization based on colonized and anticolonial forms of knowledge—does not bode well for right-wing nationalists without ethnic others like Muslims in the equation. The problem complicates into an epistemic conundrum when leaders, even from opposing ideologies, date the origins of the Sethusamudram project to the British colonial regime, thus, erroneously drawing a false equivalence of the canal scheme with the ‘destruction’ of Adam’s Bridge.

On May 16, 2007, A. Krishnaswamy, DMK Lok Sabha member for Sriperumbudur (Tamil Nadu) stirred a debate in the House by claiming that the “Sethu Samudram [sic] Project is around 150 years old project. It is the dream of the people of the Tamil Nadu … conceived by the Britishers” that could not “become a reality during the British regime” (Shri Vijay Kumar Malhotra Called the Attention, 2007). Krishnaswamy asserted that the oceanic territory was Adam’s Bridge, “not Ram Sethu” [sic], that the Sethusamudram project “was the dream of the British people … [who] called it as Adam’s Bridge” (Shri Vijay Kumar Malhotra Called the Attention, 2007). S.K. Karvendhan, Congress member for Palani (Tamil Nadu), added that the Sethusamudram project “was first proposed by a British, Mr. A.D. Taylor of the Indian Marines during 1860.” Krishnaswamy and Karvendhan were echoed by the Communist Party member for Tenkasi, M. Appadurai, who claimed that the project was the 150-year-old “dream of [the] Tamil Nadu British Naval Commander [Taylor]” (Shri Vijay Kumar Malhotra Called the Attention, 2007). Unlike Swamy, the three representatives of Tamil constituencies had no religious or nationalist attachment to ‘Ram Setu.’ But like Swamy, they reproduced selective shades of history, implying that the colonial regime was antithetical to the region’s sacred mythography.

Complex historical truths emotively reiterated by national leaders and the intelligentsia, in the form of narratemes or anecdotal fragments, can trigger fallacious understandings of history, despite the best intentions. The colonial history of Adam’s Bridge and the so-called Anglo-Tamil dream of Sethusamudram is a case in point.

As the following sections reveal, colonial plans for dredging around Adam’s Bridge were not conceived of as antithetical but complementary to the Victorian regime’s scientific and epistemic plurality that held Pamban Island’s sacred mythography as compatible with its geological history. Plans of canalizing Pal Strait were floated during the British regime but on each occasion the approved plan would not have damaged Ram Setu. Ultimately, while late-nineteenth-century colonial geology looked at Adam’s Bridge and the Hindu mythography with respect, if not outright reverence, the British administration’s refusal to dredge the sandbars was not guided by religious or spiritual but purely geological causes.

Orientalist footnotes

A good indication of the importance of Indian beliefs in the colonial imagination of Adam’s Bridge comes in the late-nineteenth-century French geographer Elisée Reclus’ (1876–1894) reproduction of the map of the region, which he titled as ‘Rama’s Bridge’ in his books, The Earth, a Descriptive History of the Phenomena of the Life of the Globe (1886) and The Universal Geography: Earth and its Inhabitants (Figures 3 & 4).

The oldest known British colonial surveyor of Adam’s Bridge and Pamban Pass was the Father of Oceanography, English geographer James Rennel; later, a founding member of the Royal Geographical Society. In 1782, Rennel published his famous map of India and, the following year, he supplemented it with his Memoir of a map of Hindoostan (Rennel, 1783), wherein he briefly suggested a proposal of deepening Adam’s Bridge to reduce the navigational challenges between India and Ceylon (Rennel, 1783, p. 35). Nineteenth-century geologists would remember Rennel as the first geographer to express a “conviction of the practicability of widening the passage for ships” (The Penny Cyclopaedia, 1841, p. 389). But along with the gaze of geologists, Adam’s Bridge’s mythography also fascinated British historians.

For instance, Robert W. Pogson’s (1828) A history of the Boondelas discussed the mythical origins of Ram Setu at length. Pogson, a captain in the East India Company’s Bengal Army, was obliging when it came to expounding on the sacred myths of Hinduism, even as Macaulay was waiting in the wings to play his part in legislating the controversial English Education Act of 1835 that would annihilate the primacy of Sanskrit, Arabic and Indian epics and mythologies. Yet, given the strong Orientalist currents of the time—spearheaded by Sir William Jones and missionaries like William Carey and William Ward—we can trace Pogson’s discourse on the Ram Setu within the epistemes of early colonial connoisseurly fascination with the Orient and the sort of colonial self-fashioning through cultural hybridity that was inseparable from the Company’s early administration in Bengal. In fact, as Pogson (1828, p. 3) pointed out, the colonial legacy of referring to Adam’s Bridge as ‘Ramu’s Bridge’ [sic] probably dated back to Jones. Here is what Pogson (1828, p. 3) says on the subject:

The following is the Hindoo account of Adam’s bridge:

When Ramu (i.e., Ram Chunder) ascertained that Ravunu had carried off Seeta, his wife, to Lunka (Ceylon), he arrived on the coast opposite with an army of 360,000 monkeys, under the command of Soogreevu, whose general Hunooman immediately leaped across the sea (500 miles) to Lunka, where he found Seeta in a garden belonging to Ravunu, and to whom he gave a ring from Ramu, and she in return sent Ramu a jewel from her hair. Hunooman then began to destroy one of Ravunu’s gardens, who sent people to kill Hunooman; but he destroyed those who were sent. Ravunu then sent his son Ukshyu against the mischievous monkey, but he also was destroyed. Ravunu next sent his eldest son, who seized Hunooman, and bringing him before his father, the king ordered his attendants to set his tail on fire. He then came to Seeta, and complained that he could not extinguish the fire on bis tail. She directed him to spit upon it, and he raising his tail to his face for that purpose, set his face on fire. He then complained, that when he arrived at home with such a black face, all the monkeys would laugh at him. Seeta, to comfort him, told him, that all the other monkeys should have black faces also; and when Hunooman arrived among his friends, he found that they had all black faces as well as himself. After Hunooman had given this account to Ramu, he proceeded to invade Lunka, but was at a loss how to lead the army across the sea. He fasted, and prayed to Saguru for three days, and was angry with the god for not appearing to him. He, therefore, ordered Lukshmunu to fire an arrow, and carry away the god’s umbrella. The god, then aroused from his sleep, exclaimed, ‘Has Ramu arrived at the sea side, and have I not known it?’ He then directed Ramu to apply to Nulu, to whom he had given a blessing, that whatever he threw into the sea should become buoyant. At the command of Nulu, the monkeys tore up the neighbouring mountains, and cast them into the sea. Hunooman brought three mountains on his head at once, each 64 miles in circumference, and one on each shoulder, equally large, together with one under each arm, one in each paw, and one on his tail. All these mountains being thrown into the sea, and becoming buoyant, a complete bridge was formed, which, however, Ravunu was constantly employed in breaking down.

The above passage, excerpted from a footnote from Pogson, is substantially quoted from another footnote in Ward’s (1817, pp. 214–215) History, literature, and religion of the Hindoos. The purpose of quoting at such length Pogson’s—and thus Ward’s—note is to show that early nineteenth-century British colonial consciousness gave a robust place to the Ramayan, in general, and Adam’s Bridge, in particular.

Much of that consciousness was generated by Thomas Maurice’s (1798) The history of Hindostan: Its arts, and its sciences. Maurice (1798, pp. 241–242) saw Adam’s Bridge through the lens of Hindu mythology that he was not embarrassed to imbibe as ‘history’. Maurice thought it was credible that “innumerable battalions of apes, or mountaineers, ha[d] constructed a bridge of rocks one hundred leagues in length,” and this “miraculous bridge” was then crossed by Lord Ram “at the head of no less formidable a body than 360,000 apes, commanded by eighteen kings, each having under him 20,000.” Maurice began as an eighteenth-century scholar of divinity, at Oxford, before turning to Orientalism and Indology. It is likely that, like the rest of his contemporaries, Maurice was affected by the spirit of the French Revolution. If so, instead of turning him against religion, it only reaffirmed his faith and, thus, what we find in his History of Hindostan is a pantheistic espousal of religious freedom in his depiction of Hindu beliefs, particularly in the way he integrated the mythographical narrative of Adam’s Bridge into his understanding of Indian culture. Maurice even used the island mythography to justify his notion of history and geological evolutions, which, in the following passage, appear as a proto-Hegelian march of history. He saw an analogy to the ancient Greek idea of metempsychosis in Ram’s magical resuscitation of the slain soldiers of Hanuman’s army after their joint victory over Ravan. More importantly, he probably sensed in Ram’s righteous victory a prophetic metaphor of Napoleonic defeat, as he took the shoal bridge at Pamban to be the living proof of that historical epoch. Thus, Captain Pogson’s footnote, derived verbatim from Maurice’s history of the Adam’s Bridge’s construction, was a reaffirmation of the colonial acknowledgment and normalization of the myths of the Ramayan.

Maurice’s history was followed by Robert Percival’s (1803) Account of the island of Ceylon. Percival did not narrate the Ramayan but adopted an anthropological style to underscore the “curious traditions among the natives” of Ceylon who, in agreement with Mahomedan and Christian myths, held their island to be “either the Paradise in which the ancestor of the human race [Adam] resided, or the spot on which he first touched on being expelled from a Celestial Paradise” (Percival, 1803, p. 51). Yet, like Maurice’s reading of Hindu myths, Percival also suggested a geological allegory in the Abrahamic myth. Percival (1803, pp. 51–52) reports:

that Ceylon at a distant period formed a part of the continent, and was separated from it by some great convulsion of nature. This account, though merely an unsupported tradition, is not altogether improbable; for when we consider the narrowness of the intervening space, and the numberless shallows with which it abounds, it cannot be denied that some violent earthquake, or, what is still more likely, some extraordinary irruption of the ocean, might have placed Ceylon at its present distance from the continent.

Maurice’s template—of acknowledging the allegorical and metaphysical validity of the construction myth of the Ramayan—would continue as the dominant trend in British colonial imagination, marginalizing the Abrahamic myth.

Another inevitable trend that can be found in colonial records between 1825 and the 1850s is that of geological explorations around Adam’s Bridge. Instead of a dialectic between Abrahamic and Hindu folklore, the new dialectic that emerged was between an Orientalist Hindu sacred mythography and plans of exploring possibilities of cutting Adam’s Bridge as part of a colonial developmental project to streamline steam communication between and around India and Ceylon. In Victorian India, therefore, a neat binary emerged between the developmental urges of colonial modernity and the still inherent need for enchantment within its factions.

Sacralizing Adam’s Bridge

Since the late eighteenth century, British historians began paying greater attention to Ceylon, which would come under British colonial control in 1802. Over the next decade, the colonial government led a series of administrative and social reforms in Ceylon, including surveying Adam’s Bridge and Pamban Channel for forging greater marine connectivity with the mainland Indian peninsula. The Mannar Channel of Adam’s Bridge was surveyed by engineers under the Ceylonese administration, including by Sir Arthur Cotton of the Madras Engineers, Captain Dawson of the Royal Engineers and James Steuart, who observed the channel to contain as little as six feet of water in the shallowest regions, which became shallower in parts that were barely three or four feet deep.

The year 1837—also the year Queen Victoria was crowned—was a turning point in the history of Adam’s Bridge. It saw the publication of the Report from the Select Committee on Steam Communication with India, containing evidence provided by Major Sim, Inspector General of Madras Engineers. Sim’s report, drafted in 1834, was one of the first detailed colonial reports on the possibilities of dredging the passage between Pamban and Mannar. Not incidentally, it was also the source of a colonial myth that once upon a time, as “given in the record of the Dutch government of Ceylon” (Martin, 1834, p. 345), a Dutch fleet had narrowly escaped the assault of a Danish fleet through the supposedly unnavigable channel of Adam’s Bridge. The anecdote was reproduced in the History of the British Colonies authored by the civil servant, and founder of the Statistical Society of London, the Colonial Society and the East India Association, Robert Montgomery Martin. Four decades later, the mythologeme would be revised to “a number of Portuguese frigates escaping from the Dutch by sailing through the passage,” in the form of an anecdote attributable to Philippus Baldaeus, the seventeenth-century Dutch minister of Ceylon (Suckling, 1876, p. 60). Though the overall impact of these anecdotes or mythologemes was marginal, they reflect a certain psychological tendency that has affected both colonial and postcolonial surveyors of Adam’s Bridge.

I use the word ‘myth’ for Sim’s (or Baldaeus’) anecdote, deliberately, though not to undermine its importance. Rather, the mythologeme is vital when seen in the context of deepening the channel. For Sim, the validity of the anecdote could depend on either the ships being small enough or the possibility that “some of the channels must have been deeper in former days” (Report from the Select Committee, 1837, p. 208) but had naturally reverted to their present formation. Because of this reason, Sim believed that Adam’s Bridge was emphatically not a safe passage to dredge or deepen the channel. He reported that even a “strong double bulwark of stones across the bank, extending into deep water on both sides, with a narrow opening of 100 or 200 feet” would not wholly control the accumulation of sandbars and corrals effected by the influence of surf and oceanic undercurrents (Report from the Select Committee, 1837, p. 208). Instead, he recommended dredging the Pamban Pass, which was moderately deep and much better suited to the purpose of deepening the marine channel. Sim recognized that the cost of dredging Adam’s Bridge and maintaining a canal there would “be very great indeed, and could only be justified by its being considered an object of high national importance to have a passage sufficiently deep in time of war for the largest vessels.” Astute enough to foresee that the marine zone could, in future, become a point of naval competition, Sim remarked that “in the event of a struggle for the superiority at sea with an European enemy, the advantages of such a channel would be invaluable”; yet, he thought it was “doubtful whether the benefits which commerce would derive from it” were enough for “an undertaking, the expense of which, under the most favorable circumstances, must be very large, and the success, from a variety of causes which neither can be foreseen nor guarded against, uncertain” (Report from the Select Committee, 1837, p. 208). Instead, the Pamban Channel “or strait between Ramisseram and the Ramnad coast” was suggested as a “prospect of a moderately deep channel such as would benefit commerce generally, and the coasting trade of India in particular, without the necessity of incurring a very large or disproportionate expenditure” (Report from the Select Committee, 1837, p. 208).

Even before Sim, Dawson had inferred that “any opening through Adam’s Bridge … would almost to a certainty be closed up, or rather brought back to its present state, by the storms which usually prevail at the commencement of the monsoons” (Campbell, 1843, p. 87). Yet, proposals to deepen the latter were floated severally, though only to be rejected every time.

Later observers, including Suckling, pointed out that Pamban Island was connected to mainland India until the end of the fifteenth century. According to the records of the Rameshwaram Temple, Pamban was “joined to the continent by a narrow neck of land until 1480 A.D., when a breach was made in it by a storm, subsequently enlarged by succeeding storms” (Suckling, 1876, p. 59). This historical fact was suitable for colonial observers who took interest in Sim’s inadvertent myth (of the legendary escape of a Dutch fleet via Adam’s Bridge). In Suckling’s time, geological and excavation campaigns had started throwing up ambiguous results on Adam’s Bridge’s history. In 1845, a huge antique anchor was excavated at Jaffna, suggesting to some hasty commentators that, a few centuries ago, regions around Palk Strait were navigable for large vessels. Meanwhile, since the early 1820s, the tidal flats of Jaffna had been coughing up a steady supply of dead chank shells. Suckling wrote that “eighty millions of them have been dug out since they were discovered without exhausting the supply” (Suckling, 1876, p. 60). Since Jaffna is at least fifty miles from Adam’s Bridge, the relics of an ancient vessel could not be taken as evidence for navigability and anchoring facilities around the tombolo. Later surveys produced no new conclusions.

Commander A.D. Taylor’s report in 1860 proposed cutting around the Pamban Passage, near Mandapam. Besides the high estimated cost of dredging Adam’s Bridge, canalizing the tombolo would leave the site vulnerable to the northeast monsoon. In 1861, Major Townsend proposed a revised version of Sim’s and Taylor’s ideas, that of deepening the Pamban Pass at a hundred thousand rupees less than Taylor’s estimate. The following year, a British Parliamentary Committee suggested cutting through Rameswaram and, in the following, the Governor of Madras, Sir William Dennison, proposed another nearby site for canalization, whose cost was estimated by Townsend at £1,372,810. Taylor, in his contribution to the Report of the British Association, made clear his disapproval of the idea of dredging Adam’s Bridge, altogether. In 1872, George Robertson, the Harbour Engineer of India, made another proposal, which yet again suggested deepening the Pamban Pass, instead of cutting through Adam’s Bridge. The new survey, conducted by Messrs. Stoddart and Robertson, estimated a budget of £660,000, less than half the previous proposed estimate. To this, Robertson made further revisions and arrived at an estimated budget of £440,000 (“The Paumben Channel,” 1873, p. 357). This radical revision was made possible, in the first place, since plans of dredging Adam’s Bridge had failed since the 1830s until they were given up altogether by the 1870s, leaving only the Pamban Channel, around Mandapam and Rameswaram as the tentative sites for deepening the strait.

In 1902, the South Indian Railway Company executed another survey, concluding Rameswaram, and not Adam’s Bridge, to be a suitable area for deepening the Channel. In 1922, Robert Bristow, Harbour Engineer to the Government of Madras, proposed yet another plan, at an estimated cost of 11 million rupees and, herein as well, suggested Rameshwaram—not Dhanushkodi or Adam’s Bridge—as the site of deepening the pass.

It was one thing to dismiss plans of dredging Adam’s Bridge due to geological constraints, but quite another for geology itself to reaffirm the ‘myth’ of Ram Setu. Late nineteenth-century colonial geology even hinted that Ram’s invasion of Lanka, following the building of the fabled Ram Setu by Hanuman’s army was “well within the limits of historical possibility” (“Sub-Recent Marine Beds,” 1883, p. 74). Implying that the Ram Setu myth was an anthropomorphized narrative of a geological saga, the Memoirs of the geological survey of India ambiguously remarked that “such elevation of the sea bottom would unquestionably be regarded as a miraculous event and ascribed to superhuman agency, and the fervid imagination of successive Aryan bards may be easily credited with sufficient powers of invention to have evolved all the marvellous details that have been superadded” (“Sub-Recent Marine Beds,” 1883, p. 74). Even more direct and unambiguous were the suggestions of Walther, whose report was published in the Records of the Geological Survey of India. At Palk Strait, Walther (1890, p. 116) noticed the phenomenon of coral and marine skeletons and subsequent sedimentary depositions, although much of Adam’s Bridge, according to him, comprised “small and great blocks of sandstone which being cemented together by a sandstone matrix form a giant conglomerate.” This observation compelled him to conclude that “Adam’s Bridge existed once, a long time ago; that it was destroyed by unexplained causes, and that the fragments were again recemented only to be broken asunder again in the beginning of the fifteenth century.”

Seeing the colonial episteme take on a compatibilist stance, Indian nationalists were not far behind. Thus, Indian nationalist thinker Nobin Chandra Das opined that Ceylon was once part of India’s Deccan region and had been severed from the mainland by a volcanic eruption; that the islands and shoals between Rameswaram and Mannar were more numerous and shallower, so that Ram’s army could fill them with timbers with much greater ease than possible in the present epoch (Das, 1896, pp. 46–48). Such notions were not confined to Hindu or Indian observers. Colonial geology under Robert Bruce Foote (director of the Geological Survey of India from 1887 to 1891) shared many facets of the fantastic explanation. Colonial railway developments around Pamban also tried to maintain compatibility with Hindu mythography. The building of India’s first sea-bridge—the Pamban Railway Bridge—in 1914, was practically staged as a recapitulation of “the building of the Ram Setu, from Dhanushkodi to Sri Lanka” (Chatterjee, 2018, p. 112). In May 1914, the Journal of the Royal Society of Arts published an article on the newly formed railway channel between the India and Ceylon. It acknowledged the mythography of the region, while briefly reproducing the legend of Ram Setu, as though in reminiscence of Maurice’s History of Hindostan. The article referred to the opening of the Indo-Ceylon Railway (established February 24, 1914) in terms dating “back from mythological times, for it presented itself to Rama when he determined to invade Ceylon to recover his consort, Sita, who had been carried away by Ravan, the demon king of Ceylon” (“Railway Connection between India and Ceylon,” 1914, p. 525). Clearly, the article was not only a celebration of British engineering but also of the Indian civilizational myths that had inspired that engineering. “It is interesting to note,” the article went on, even more dramatically, “that the viaduct is built entirely on the identical causeway which Rama’s monkey friends are credited with having constructed thousands of years ago” (“Railway Connection between India and Ceylon,” 1914, p. 525).

Epilogue

The colonial records—I have reproduced briefly for want of space—bear overwhelming evidence for not only the fact that British surveyors found Adam’s Bridge to be unsuitable for canalizing Palk Strait but also that nineteenth-century geological and railway developments around Pamban actively paved the way for a nexus between colonial and nationalist epistemes of historicizing Adam’s Bridge. Looking at early twentieth-century colonial accounts revolving around the railways, such as Edgar Thurston’s (1914) The Madras presidency or the Illustrated guide to South Indian railway (1926), we find further evidence of how the colonial regime reaffirmed the religious and spiritual geography of Southern India through the Hindu imagination (Chatterjee, 2018, pp. 113–115). Contrast this with Swamy’s tirade from 2007, where he criticized DMK-leader Karunanidhi and the anti-Brahminical Dravidian movement of being taught historical lies by “British Imperialists … for eight decades.” It is not Swamy’s narrative alone that is inaccurate, or that of the Sangh Parivar, but a much larger gamut of political and academic opinions that have contorted, selectively quoted or simply evaded the question of colonial sympathies with Ram Setu’s mythography.

Wendy Doniger’s (2009, pp. 664–666) The Hindus: An alternative history took a critical stance against nationwide protests by Hindutva activists opposing the Sethusamudram project, noting that scientists questioned the idea that Adam’s Bridge is a humanmade structure. Doniger’s reference was to the 2002 NASA images of Adam’s Bridge that excited Hindutva activists who claimed them to be the indubitable proof of the existence of Ram Setu. NASA officials refused to confirm or deny such claims. However, in January 2018, American scientists appearing in a documentary on the Science Channel made the spectacular claim that the sandbars of Adam’s Bridge were, in fact, relics of a humanmade monument (Could This Be The Legendary “Magic Bridge” Connecting India And Sri Lanka?, 2020). Around that time, India’s ruling establishment—the BJP, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi—renamed three islands of the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago. Ross Island was renamed as Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Dweep, Neil Island changed to Shaheed Dweep and Havelock Island styled as Swaraj Dweep. This is part of a larger nationalist and political campaign of renaming Mughal-era and British-era towns, provinces, stations, roads and cities that has been a political priority of the BJP. The additions of Sri Hanuman Pratima and Setu Chandra Dweep on Google maps imagery, in the context of Adam’s Bridge, constitutes a wider trend of nationalistic renaming and reclaiming of lost symbols of India’s civilizational identity. The latter two names fundamentally alter the epistemic framework in which to see Adam’s Bridge, for they, somewhat deceptively, suggest that some parts of the Setu are, at least, psychologically inhabitable, where Hindu idols or symbols can be (re)habilitated and worshipped. But Hindutva activists, their political opponents and scholars like Doniger do not acknowledge that British colonial geology was instrumental in shaping this nationalist consciousness, which, oftentimes, doubles up as post-facto anticolonial ideology. And where DMK and Congress leaders, who stand in favour of the Sethusamudram project, go wrong is to see the shipping canal project as a British ‘dream’ at the cost of demolishing Adam’s Bridge.

As this paper has demonstrated, ‘Hindu’ or ‘Indic’ beliefs in the sacred mythography of Ram Setu were actively facilitated by non-Indian colonial actors from British India, without jeopardizing the colonial project. Therefore, neither are Hindutva assertions on Ram Setu default anticolonial positions that can restore enchantment within the sphere of modernity, nor do developmentalist and secular mobilizations in support of the Sethusamudram possess strong precedents of the colonial regime planning to dredge Adam’s Bridge as a possible site of canalization.

By laying Adam’s Bridge’s colonial bogey to rest, at least two indirect purposes will be served. The public discourse can be better channelized to focus on two issues of national importance unfolding on the islands around Adam’s Bridge.

First is the case of the endangered and drowning islands of the Gulf of Mannar (Thiagarajan, 2020).

Second is that of Katchatheevu island. At about 20 kilometres from Adam’s Bridge lies the controversial Katchatheevu island, once Indian, today a Sri Lankan territory. It was ceded by Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to Sri Lankan Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, in 1974, although the cessation was never sanctioned by the Indian Parliament. Hence, Katchatheevu is a disputed territory between the two nations, largely affecting the lives of poor Indian fishermen who are led astray into Sri Lankan waters and are kidnapped or arrested (Nath, 2022).

Above all, I have tried to use Adam’s Bridge’s colonial historiography as a case study to problematize de facto correlations between anticolonial thinking and decoloniality. While Hindutva activists want to give historical recognition to the mythographical Ram Setu, by claiming it as a heritage monument, such a project cannot be delinked from the footprints of colonial historians, Indologists, surveyors and geologists, who ironically, nurtured the myth unbeknownst to today’s nationalist and secular historians alike. While it took the occult imagination of nineteenth-century theosophy to reimagine, historicize and re-enchant the lost world of Lemuria, even the seemingly disenchanting ideologies of the British colonial regime were more than capable of preserving the enchanting fables of India’s ancient bridge.

Acknowledgements

The author is deeply grateful to Adam Grydehøj for his constant encouragement, May Joseph for her continuous intellectual engagement with my paper, and the anonymous reviewers of Island Studies Journal.

_and_set_chandra_dweep_(denoting_symboli.png)

_and_set_chandra_dweep_(denoting_symboli.png)