1. Introduction

CEOs and their particular characteristics can have profound impacts on the firms they lead, especially on strategic decisions like International Entrepreneurship (IE). IE has been largely defined as an opportunity-oriented process involving recognition and exploitation of opportunities beyond domestic markets (Oviatt & McDougall, 2005). This process particularly involves identifying the opportunities a firm may gain when venturing abroad by directly, or indirectly, competing with domestic or foreign suppliers in that market. The phenomenon of IE has received much attention from scholars, yet many opportunities remain overlooked.

The effects of CEO characteristics on firms’ strategy have been understudied in the case of island-based firms (IBFs), which are located in some of the smallest countries in the world. In IBFs, top executives must be additionally tasked in order to be flexible in responding to internal and external shocks as a consequence of vulnerabilities related to island size (Baldacchino, 2019). Briguglio (1995) indicated insularity equips nations with distinct susceptibilities, such as the ability to develop and maintain limited human capital at par with other nations, deal with less geographic and product diversification, as well as face more limitations regarding resources and technology (Kurecic et al., 2017; Thompson et al., 2019). With respect to CEOs of IBFs, having a limited pool of qualified candidates may influence the ability of firms to capitalize on strategic opportunities such as IE in order to expand their boundaries.

Upper echelons theory (Hambrick & Mason, 1984) predicts that the strategy and performance of a firm is dependent of its CEO’s vision, which is fundamentally shaped by the executive’s characteristics (particularly socio-demographic and psychological traits) (Abatecola & Cristofaro, 2020; Hsu et al., 2013). In small islands there are a finite number of companies that can operate locally and a lack of economies of scale; therefore IE represents a means to survive and expand. Furthermore, this strategic decision is immersed in a context with two additional challenges, related to the small size of the islands: adaptation and innovation (Hall, 2012). Thus, IE decisions of CEOs of IBFs consider other variables and require particular characteristics that have not been addressed in the previous literature. This work is a pioneer in investigating the characteristics of the CEOs that promote IE in these companies and contributes both to the international literature on the subject, as well as to the emerging literature on island studies. In particular, it aims to analyze the influence on IE of CEO’s tenure, academic background and achievement, family allegiance, and international exposure, taking into account the small island particularities.

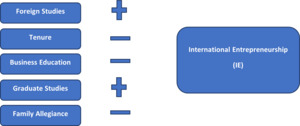

This research considers a sample of listed IBFs from eight small islands: Barbados, Cyprus, Fiji, Iceland, Jamaica, Malta, Mauritius, and Trinidad & Tobago, for the years 2009-2018. Results show that CEOs’ Family Allegiance (being part of the business family, for family firms), Tenure (number of years the CEO has served in that position with the company), and Academic Background (if the CEO majored in Business Administration, Finance, Accounting, or Economics) are negatively associated with IE, while CEOs’ Academic Achievement (when the CEO pursued graduate studies) and International Exposure (if the CEO studied abroad) are positively related with International Entrepreneurship. Some of these results are atypical in the existing literature; however they are very consistent taking into account social network theory for the small island context. Social network theory emphasizes the importance of social relations in transferring information and influencing behaviors (W. Liu et al., 2017).

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 deals with the literature review and hypothesis building; Section 3 discusses the data, variables, and methodology associated with the testing of the hypotheses; Section 4 provides the results and discussion; conclusions are exposed in Section 5.

2. Literature review

2.1. CEOs and international entrepreneurship

International entrepreneurship (IE) is a type of entrepreneurship that goes beyond local frontiers. It searches opportunities outside local markets to increment positioning and profits. As such, internationalization is an entrepreneurial act, which implicates innovation, risk-taking, and strategic change (Schumpeter, 1934). International entrepreneurship is defined as “a combination of innovative, proactive, and risk-seeking behavior that crosses national borders and is intended to create value in organizations” (McDougall & Oviatt, 2000, p. 903). IE comprises “cooperative alliances, corporate entrepreneurship, economic development initiatives, entrepreneur characteristics and motivations, exporting and other market entry modes, new ventures and initial public offerings, transitioning economies, and venture financing” (McDougall & Oviatt, 2000, p. 903).

The backgrounds of executives determine the interpretations of opportunities and the decisions they make to act upon these opportunities, as is derived from upper echelons theory (Hambrick & Mason, 1984; Nishii et al., 2007). Specifically, upper echelons theory addresses the impact of executives’ personal characteristics such as age and gender, as well as their professional characteristics such as tenure and educational background, on companies’ outcomes. Even though upper echelons theory has not been exempt from criticism from a methodological and conceptual point of view, it is still one of the most widely used theories in management research (Neely et al., 2020).

Upper echelons theory has been expanding over time, incorporating more characteristics of corporate top management, as well as introducing moderating variables. One characteristic that has been introduced is CEO connectedness; it has been empirically proven that the access to and strength of CEOs’ social networks favor business profitability (D. Liu et al., 2018). This is in line with social network theory (Granovetter, 1973), which posits that connectivity fosters trust, information flow, and innovation, which in turn promotes profitability. Regarding moderating variables, three of these are the external environment, managerial discretion and job demand, which are dependent on the specific context and culture where the firms operate. There has been a bias towards studies performed in American and European settings; lately the literature has introduced many papers based on Chinese firms. Regarding CEO characteristics, psychologic variables have been added to the increasing list of socio-demographic variables (Abatecola & Cristofaro, 2020).

Several papers under the upper echelons theory framework highlight that CEOs’ vision, shaped by their characteristics, is paramount for determining firms’ strategic decisions such as IE (Gentile-Lüdecke et al., 2019). The international experience of top executives is a variable that has been widely used to explain the international orientation of the companies they lead (B. B. Nielsen & Nielsen, 2011; Sambharya, 1996). In addition, there is evidence that the international experience of managers is reflected in greater financial performance, compared to other local companies (S. Nielsen, 2010). CEOs direct their firms to expand across borders in response to their vision and an array of (both domestic and international) developments, and new environments/spaces and conditions should be explored to better understand the process by which IE takes place (Coviello et al., 2011; Kiss et al., 2012).

IE is a phenomenon where businesses transform into fundamentally different organizations through operating in multiple markets that contrast with the structure, dynamics and culture of their domestic market (Fletcher, 2004). They outperform their peers through the ability to scale across several markets, as well as extracting value from the network they build through their presence in foreign countries (Lu & Beamish, 2002). Firms engaged in IE are defined as those that operate a controlling interest in a foreign subsidiary (Wang et al., 2015), which make matters regarding IE part of their strategic decision making. The role of executives in IE has been well supported, with evidence pointing at the profound and critical role of executives in the process of IE (Chen et al., 2019; Gentile-Lüdecke et al., 2019; Wrede & Dauth, 2020). However, up-to-date studies have practically ignored contexts such as small island-based firms.

2.2. Small islands and island-based firms

Research on the relationship between IE and CEO characteristics is vast for emerging and developed economies, and incorporates companies of varying sizes (D’Angelo & Presutti, 2019; Dimitratos et al., 2016; Pacheco, 2016). Geographical aspects have been found to interact with strategic decisions such as IE, but have left plenty of overlooked spaces, such as small islands (Acs & Correa, 2014; Booth et al., 2020). Small islands have often been relegated as less complex and minute forms of advanced markets, which apparently do not contribute to scholarship. The contrary, however, is true if seen from a perspective of ecosystems, as small islands are similar to each other in terms of islandness (Patiño et al., 2017). Small island conditions tend to be common to all, regarding business environments, infrastructures, and networks, which allow for wider applications and generalizations (Lomolino, 2016).

Small islands have unifying conditions; they typically face the challenge of small population, risk aversion due to reputation considerations, and susceptibility to external shocks (Booth et al., 2020; Briguglio, 1995; Briguglio et al., 2006). A small environment (few players and resources) provides for limitations that require alternative strategies from those already established in theory (Williams et al., 2020). Competitive pressure, for example, can be higher in small island markets that are filled with local homogeneous products (Sannegadu et al., 2021). Product diversification is a challenge on small islands since there is a general lack of economies of scale that do not allow higher domestic production and further specialization (Mohan, 2016). In this respect executives face additional challenges in their pursuit to sustain and grow the firms they lead (Ackerman et al., 2020) in the domestic market. In addition, firms in small islands have found it difficult to attain brand recognition overseas, which increases the risk of IE (Lawton & Harrington, 2007). International entrepreneurship of IBFs has been documented mostly as a reactive strategy; that is, companies consider and pursue international endeavors as a reaction to adverse local conditions such as market saturation (Sannegadu et al., 2021).

On the other hand, social network theory suggests that having long and engrained relationships with the market and its players can create unique levels of trust and sharing of information that discourage entrants or competitors’ ability to diffuse through the small island market. Consequently these conditions may reduce the odds of these firms to engage in IE, due to their strategic fit with their domestic market. Social networks are defined as “a pattern of ties linking a defined set of persons or social actors” (Seibert et al., 2001, p. 220), which promotes cooperative efforts and aids the transfer of thoughts, information, and knowledge among the network members (Fliaster & Spiess, 2008). Social (business) networks are positively correlated with financial performance (Cárdenas, 2014); firms can better resist uncertainty and volatility in their particular environment through these networks (Martin et al., 2015).

Island environments undoubtedly present limitations for IBFs; however at the same time they allow for advantages of their own. One of the advantages relates to small island executives’ strategic flexibility (Baldacchino & Bertram, 2009), which represents a means to cope with substantial external shocks through adaptation and innovation. Small islands are characterized by changeability; in order to survive islanders must adapt constantly and be resilient (Gillis, 2014). The latter might favor strategies such as IE, which requires CEOs openness to changes and new developments. But, CEO’s strategic flexibility can also strengthen the company’s presence in its local market, making it unnecessary to look after more risky foreign projects. For example, strategic flexibility increases the success odds of niche products, which represent an opportunity to remain competitive in the local market (Kurecic et al., 2017).

Social networks allow CEOs to obtain relevant information that can further expand their companies’ strategic flexibility. From a knowledge management perspective, information and knowledge provided by social networks enhance strategic flexibility (Mihi et al., 2012), allowing the firms to adapt better to the markets’ volatilities and favoring their competitive advantages; the latter is particularly important in more uncertain environments (Fernández et al., 2014), such as those present at IBFs.

Minto-Coy, Lashley, and Storey (2018) pointed out that IBF issues are misunderstood and inappropriately addressed, and have called for further examination. IBFs operate like major players in their domestic market but are typically small- and medium-sized enterprises and are thus less complex in terms of organization. This dichotomy possibly disguises the opportunities beyond borders to an extent that renders IE a (more) remote strategic goal. Broome, Moore and Alleyne (2018) pointed out that (Caribbean) IBFs faced funding challenges to engage risk projects (e.g. R&D), which underscore a striking limitation IBFs face in crafting plans to grow and expand.

These conditions undoubtedly distinguish IBFs from those firms examined in previous studies and introduces small islands as new environments for IE research (Baldacchino, 2006, 2007). It is yet, however, unknown how these dynamics frame decision-making on IE by CEOs of IBFs, prompting the need to extend upper echelons theory and social network theory to better inform on how this process comes about.

2.3. CEO characteristics and international entrepreneurship

CEOs’ decisions are motivated both by natural characteristics (e.g. gender, age) and acquired characteristics (e.g. education & training, tenure), and can form the basis for which they are selected to lead their firms (Carpenter et al., 2016). CEOs profoundly impact the outcomes of their companies by virtue of their leadership and choices. Studies have specifically identified the link between the personal characteristics and attitudes of CEOs, on the strategic behavior of firms with regard to IE (Anwar et al., 2018). Nevertheless, this is a practically unexplored area of research for IBFs (Sannegadu et al., 2021).

2.3.1. International exposure and IE

IE depends on several CEO characteristics, one of them being their international exposure through foreign experience and/or education (Casillas et al., 2015). Executives with foreign experience are more likely to push forward internationally oriented decisions with regards to sourcing and expansion (Chen et al., 2019). These CEOs have better knowledge on different business cultures, as well as greater international networks, which foment IE (Zucchella et al., 2007). Recent studies highlight that CEOs’ familiarity with specific markets reduce uncertainty and are a determinant of IE (Clark et al., 2018). In addition, CEOs that have studied abroad are expected to engage more in IE, as they have attained a more global mindset (Cumming & Zhan, 2018). Lack of international exposure has also been identified as a barrier to developing the most basic international elements of businesses, such as exports (Bianchi & Wickramasekera, 2016).

Islanders pursuing higher education at institutions abroad are exposed to international environments (Alexander, 2015). The latter is also true for island foreign residents that have studied off-island. This allows the importation of new knowledge and practices, as well as connections to new and foreign networks that facilitate the interpretation of opportunities abroad. Therefore, it is expected that in the context of small islands, international exposure contributes positively to the IE of IBFs, which leads to Hypothesis 1:

H1: The odds for international entrepreneurship in IBFs are higher when CEOs have studied in foreign universities.

2.3.2. CEO tenure and IE

Tenure is a proxy of the CEO’s experience and seniority in office and at the company. It is related to the age of the CEO and his/her career as a senior executive. Image and reputation of the CEO, and by extension of the firm, are carefully managed by the CEO as their tenure grows (Conte, 2018). Therefore, risky projects such as R&D and IE are carefully reviewed before becoming actionable by firms (Hou et al., 2013). It is believed that tenure allows for the development of acumen, generating a foundation for less risky decision making as time progresses (Rupinder & Balwinder, 2019). Findings from manufacturing industries have found discouraging links between tenure and IE, as CEOs grow conservative over time (Huybrechts et al., 2013; Lee & Moon, 2016). CEOs would thus prefer other less risky strategic activities to expand abroad, such as exports.

Tenure in this respect encourages commitment to established ideas and practices which may deter IE. Greater knowledge of the home market, greater reputation acquired over time, and deeper local networks enjoyed by a CEO with greater seniority, foster the status quo against strategies like IE and promote employing strategic flexibility in the local market. As such it is expected that tenure of CEOs in IBFs would discourage IE, rendering the second hypothesis:

H2: CEO tenure is negatively associated with the odds of IE in IBFs.

2.3.3. Academic background & IE

University education in Business, Economics, Finance, Accounting or related fields provide CEOs with tools to better manage the companies they lead, as well as training that supports IE (Andersen & Rynning, 1994). CEOs with management educational credentials are more flexible and capable of implementing strategies such as IE, in order to take advantage of opportunities in foreign markets (Goll et al., 2007). Understanding the dynamics of business, particularly the drivers of performance in different organizational settings, enables those CEOs with management backgrounds to detect opportunities better.

Nevertheless, in small islands the above might not apply. Baldacchino and Bertram (2009) present the concept of strategic flexibility as a means to cope in small environments that face substantial external shocks. Based on the theory of niches, they elaborate that islanders acquire a skill of internal flexibility, as a strategy to survive with the array of shocks and returns that they may face. A later publication by Baldacchino (2019) concludes that CEOs of IBFs can craft locally profitable and oriented strategies like market penetration, through uniqueness and quality of certain products and services. Executives with relevant management training and good understanding of strategies that can deliver on the short run may thus perform well in these firms, as they may be able to command and shift between strategies matching market developments, and relegate IE to the backseat. For example, executives with backgrounds in Economics, Accounting, Finance and Business are often considered those more poised to lead their firm to expand internationally because of their profound understanding of commercial organization and economic environment (Kokeno & Muturi, 2016; Teixeira & Correia, 2020). However, small island settings can lead to the opposite effect and seem counter-intuitive to mainstream interpretations of how business training equips executives.

Under the notion of islandness, where the presence of risk aversion that an internationalization strategy entails is inherent, CEOs tend to promote IE as a reaction and not a natural inclination for the growth and positioning of firms (Sannegadu et al., 2021). Thus, those companies that cannot compete locally might be the ones that mainly seek this type of strategy to survive and expand. Social network theory posits that CEOs who have broader and stronger networks are more likely to succeed in the local market and avoid international endeavors, since they can increase their strategic flexibility based on greater information and knowledge sharing. This theory can become more robust considering not only the size and strength of the networks, but also CEOs’ abilities to take advantage of the greater information and market knowledge derived from these relationships. As such, majoring in Economics, Accounting, Finance and Business fosters the capabilities of these CEOs to benefit from their networks. According to Durán et al. (2016), training in these areas increases CEOs’ abilities to process information, accept new ideas, work in teams, and foment innovation and R&D. Furthermore, it was documented that CEOs with these academic qualifications tend to react faster to changing market conditions and make better decisions, which favors strategic flexibility.

The detection of opportunities is then framed by the island context which may promote the utilization of other island skills such as strategic flexibility (Baldacchino & Bertram, 2009), to which the following hypothesis is formulated:

H3: CEOs of IBFs that majored in Business Administration, Economics, Finance, Accounting, and related fields reduce the odds for international entrepreneurship.

2.3.4. Academic achievement & IE

Advanced academic programs provide CEOs with socio-cognitive skills to comprehend multifaceted issues with regards to firm organization and strategy (Goll et al., 2007). Highly educated CEOs have shown a bigger inclination towards further learning and incurring in new projects (Hitt & Tyler, 1991). Greater educational qualifications make CEOs more adaptive to changes in the business environment and more willing to implement complex strategies such as IE (Goll et al., 2007; Jafari et al., 2020). Education foments better information processing and risk analysis, which translates into more adequate decisions. The latter positively impacts local and international entrepreneurship (Amorós et al., 2016).

Allahar & Brathwaite (2017) conclude that graduate studies, especially those that include entrepreneurship in the curriculum, are beneficial for Caribbean executives in their efforts to expand their companies beyond their borders. The high educational level of the CEOs of IBFs allows the exploration and exploitation of opportunities outside their national markets. This makes them less risk averse and more prone to IE. The above brings forward the following hypothesis:

H4: CEOs of IBFs who have completed graduate studies increase the odds for international entrepreneurship.

2.3.5. Family allegiance & IE

Family businesses tend to be more conservative than non-family firms, which reduces the odds for IE (Watkins-Fassler & Rodríguez-Ariza, 2019). Regarding CEOs of family firms, it has been exposed that non-family CEOs are more likely to pursue IE than family CEOs (Huybrechts et al., 2013). Non-family CEOs are perceived as to be more independent and are likely to perform better, as they are less inclined to be involved in family conflicts (Alayo et al., 2019). In addition, CEOs that are members of the owning family might be less suitable for the job and more doubtful about pursuing complex strategies such as IE. Debicki, Miao, and Qian (2020) provide evidence that the greater the participation of family members in the management of family businesses, the lower the benefits obtained from IE. In a similar line, Sánchez-Marín, Pemartín, and Monreal-Pérez (2020) show that family firms are significantly different from others in terms of converting the benefits of exporting into product innovation.

IBFs in small societies may be more predisposed to family members heading the firms because it is hard to trust someone from outside, especially when it is difficult to find someone talented. It is expected that these executives, and the organizations they lead, are less likely to be exposed to migration and more likely to perpetuate family traditions, leading to a discouraging relationship with IE. Considering the additional vulnerabilities of small islands, the following hypothesis is adopted:

H5: CEOs’ Family Allegiance is negatively associated with the odds of IE in IBFs.

3. Data and methods

3.1. Data

The dataset for this research is sourced from the annual reports of island-based firms (IBFs) listed on the stock exchanges on the islands. These data sources are publicly accessible, which facilitates their use. The most common frame to delimit islands is the UN classification: Small Island Development States (SIDS; see UN-OHRLLS, 2020). This group of nations include states such as Belize, Guyana and Suriname (which for historical reasons are also considered as islands), as well as Singapore and Bahrain which were considered developing nations at the time of identification. Conversely islands in Europe such as Malta, Cyprus, and Iceland are not considered developing countries and therefore not included as SIDS, although they possess similar characteristics in terms of population size.

Most of the literature views smallness according to population (MacFeely et al., 2021). Hein (2004) classified islands as being small if they have less than 5 million inhabitants. This study uses this definition and identifies a sample of small islands with securities exchanges including more than one company headquartered on the island. Ultimately, this research delimited to the nations of Barbados (286,641 inhabitants during 2018 - smallest island in the sample), Cyprus, Fiji, Iceland, Jamaica (2.935 million inhabitants during 2018 - biggest island in the sample), Malta, Mauritius, and Trinidad & Tobago for the years 2009-2018. Companies with fewer than three years of data were dropped from the dataset, as well as those that delisted for a major part of the period or had incomplete CEO information, a total of 23 firms. The final sample is composed of 164 firms. The data was mainly obtained from the companies’ annual reports, which are available online and reviewed manually. The manual revision was generally of extreme added value as it revealed important aspects of firms, including internationalization. It also enabled the collection of data on the CEO including their tenure as CEO, as well as identifying their academic background and academic achievement, i.e. having completed a graduate degree. This review also enabled the collection of data on whether the CEO enjoyed higher education abroad, versus having studied domestically. This strategy also facilitated the detection of family involvement in firms, as many self-identified as family firms in their annual reports, whilst not always having a family member as CEO. This process rendered 1459 observations and an overview is presented in Table 1.

3.2. Variables

The following variables have been constructed from the data above:

A. Dependent Variable: International Entrepreneurship (IE). IE is approximated by a dichotomous variable, being 1 if during a particular year the company had subsidiaries or branches in foreign markets and 0 otherwise. On average, 40% of the companies under study participated in this type of foreign endeavor.

B. CEO Characteristics: b1. Family Allegiance (FA). Referring to the CEO being an appointed family member or not. 85% of the 46 Family Firms identified in the panel had a family member appointed as CEO. This means that around 24% of the 164 companies contemplated are being run by a family businessperson. b2. Tenure (TE). It refers to the number of years the CEO has worked in the firm as CEO (mean value 9.5 years; longest tenure being 59 years); b3. International Exposure (IX). It is approximated by a categorical variable, being 1 if the CEO studied abroad, and 0 otherwise (on average 78% of CEOs have attended foreign university education); b4. Academic Background (AB). It is constructed as a dummy variable, being 1 if the CEO majored in Business Administration, Finance, Accounting, or Economics (on average this is the case for 81% of CEOs), and 0 otherwise; b5. Academic Achievement (AA). It is measured by a dichotomous variable, being 1 if the CEO pursued graduate studies (the mean value is 52%), and 0 otherwise.

C. Control Variables: c1. Firm Size (FS). It is measured by the natural logarithm of total assets. c2. Return on Equity (ROE). This variable reflects book value, and is calculated as net income over equity. Values greater than 100% in absolute value were excluded as outliers. The average ROE observed in this study was 8.2% for all islands with Trinidad & Tobago reporting the highest (19.6%) and Cyprus the lowest (-2.6%).

3.3. Methodology

The relationship between International Entrepreneurship (IE) at IBFs and CEOs’ Characteristics (CCs) is empirically studied through a binary probit model. There are several estimation methods that can be employed under the presence of binary dependent variables (such as IE). The two most common ones are probit and logit. The difference between one and another has to do with the specification for the cumulative distribution function of the error terms: probit (standard normal), logit (logistic-similar to normal but with thinner tails). There is arbitrariness in selecting a probit or logit method, as they provide very similar results. Following previous studies on IE, it was decided to work with a probit model (Pinho & Martins, 2010; Watkins-Fassler & Rodríguez-Ariza, 2019; Wennberg & Holmquist, 2008; Wu & Ang, 2020). The use of the probit method in this study allows to determine how the probability of IE increases or decreases (and in what percentage) according to the particular characteristics of the CEOs of small island-based firms.

The dependent variable (IE) takes a binary form, and is regressed with the CCs to define how likely they are to determine the IE category of these firms. For this model, a significant positive (negative) sign on an independent (and control) variable’s parameter indicates that greater values of the variable increment (reduce) the odds of IE. Heteroscedasticity is taken into account by employing QML (Huber/ White) robust standard errors to correctly address the unknown structure of variance in the estimators. Marginal effects are attained for all significant explanatory and control variables (p-value<0.01). Hence, the following equation is formulated:

IEit=∂0+∂1FAit+∂2TEit+∂3IXit+∂4ABit+∂5AAit+∂6FSit+∂7ROEit+μit,

where: refers to the company; is time; is the constant term; corresponds to the dependent variable: International Entrepreneurship; and are the CEO Characteristics: Family Allegiance, Tenure, International Exposure, Academic Background, and Academic Achievement; and are the control variables: Firm Size and Return on Equity; is a random error term.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

On average, 40% of IBFs are engaged in IE. Nevertheless, there is great variation in this respect between the islands, with Jamaica, Trinidad & Tobago, and Barbados (all member states of CARICOM) the ones showing more international entrepreneurship. At the other extreme appear Fiji and Malta, with Fiji being a non-democratic country and Malta, although an EU member state since 2004, has faced the challenges of being the smallest of the EU member countries (484,630 inhabitants during 2018).

About 24% of firms self-identified as family businesses had a family member CEO during the observed period. Cyprus shows the highest propensity for this business practice (Fiji and Iceland the lowest), which coincides with its family patterns. According to the Cultural Atlas, Cypriots perceive their big extended family as immediate family, which is the basis of their social and economic life. On the contrary, family patterns for urban Fijians and Icelanders are based on much smaller nuclear families.

CEOs’ average tenure is observed at 9.5 years with high turnovers in some companies and a long tenure of 59 years in one firm. It is not surprising that mean CEO Tenure is significantly higher in Cyprus than in the rest of the islands, where the presence of family member CEOs is a more common practice. CEO changes are uncommon when these executives belong to the business families, due to a lack of succession planning and less sensibility of turnovers to performance (Watkins-Fassler & Briano-Turrent, 2019).

CEOs of IBFs on average tend to be highly educated: 81% attained a university degree in Business Administration, Finance, Accounting, or Economics; 52% pursued graduate studies. Most of CEOs completed their studies at foreign universities (mean value of 78%), which indicates a substantial international outlook of CEOs of IBFs. Although CEOs of IBFs are on average noticeably well trained as leaders for their firms, there are some differences in this regard among the islands. Particularly for Academic Achievement, Cyprus is the island with the lowest average presence of CEOs with graduate studies (21%). On the contrary, Iceland and Jamaica share the highest position regarding the percentage of CEOs with graduate education (73%). Also, with respect to international exposure, Barbados and Mauritius show the greatest percentages of CEOs trained abroad (100% and 97%, respectively). In contrast, Malta and Iceland are the islands with the least presence of CEOs with foreign studies (50% and 58%, respectively).

The correlations between the variables are shown in Table 3. All of the explanatory and control variables correlate significantly with International Entrepreneurship of IBFs, measured by the dichotomous variable IE (being 1 if during a particular year the company had subsidiaries or branches in foreign markets, 0 otherwise). This finding validates the explanatory power of these variables on IE and justifies their inclusion in the model.

When dealing with multiple variables it is important to determine if additional treatment is necessary in case there is multicollinearity. Multicollinearity makes it difficult to estimate the parameters with precision and determine the effect of each individual variable on the dependent variable. In its presence, large standard errors, and therefore low t-statistics, are shown. So, coefficients tend to be not significant. Variance inflation factors (VIF) measure the level of collinearity between the independent (and control) variables. If they are too high, it is recommended to use multivariate statistical techniques to take account of multicollinearity; centered VIF values below 10 are commonly acceptable.

Excluding IE for being the dependent variable, the greatest correlations observed are between CEO Tenure (TE) and Family Allegiance (FA), and among CEO Tenure (TE) and Academic Achievement (AA). However, in all cases centered variance inflation factors are less than 10, as shown in Table 4. The highest value is observed for TE (1.18), followed by FA (1.17) and AA (1.09); therefore, multicollinearity does not require any further treatment.

4.2. Main findings and discussion

The econometric results of the relation between International Entrepreneurship (IE) and CEOs’ Characteristics (CCs) are exposed in Table 5, whereas marginal effects for the most significant explanatory and control variables (p-values<0.01) are shown in Table 6.

Except for ROE, all explanatory and control variables determine to some extent IE and go in line with the hypotheses established. Family Allegiance (FA), Tenure (TE), and Academic Background (AB) are negatively associated with IE. Family-member CEOs on islands may be locked into more conservative thinking promoted by family values and isolate the companies they direct (Binacci et al., 2016). In addition, they tend to have attained comparatively fewer skills through graduate education, which makes it more difficult for them to pursue complex international endeavors (Pinheiro & Yung, 2015). In fact, the data shows that only 36% of islands’ family CEOs have graduate studies; in contrast, 57% of non-family CEOs accomplished graduate education. Also, it is well documented that family businesspeople are more risk-averse and have longer tenures, both reducing the odds for internationalization (Aparicio et al., 2017). Indeed, according to the data, average tenure for family CEOs of IBFs is 15 years, while being 8 years for non-family CEOs.

Marginal effects show that for each increment of 1 year in a CEO’s tenure, the firm’s probability of expanding through subsidiaries or branches abroad decreases by 1%. Less experienced CEOs may be more eager to operate in other countries and deal with new types of customers, competitors, and investors (Alexander, 2015). For those with greater tenure, the above requires an adaptation of risk aversion and cognitive processes in order to bring forward international entrepreneurship. This finding supports Hypothesis 2: CEO tenure is negatively associated with the odds of IE in IBFs.

The probability of IE decreases 21% when the company’s CEO majored in a business-related field. The negative association between Academic Background and IE is generally speaking a rare finding. However, it makes a lot of sense in the context of small islands and islandness, where IE tends to be a reactive rather than proactive strategy due to risk aversion. IBFs that are not exposed to migration and extinction isolate, adapt, and specialize in the domestic environment. Islands can expand their possibilities to sustain local companies as long as they have the capacity to innovate and adapt (Baldacchino & Bertram, 2009). CEOs trained in Business Administration, Finance, Accounting, or Economics have better skills for information processing and strategic planning, which facilitates innovation and R&D (Durán et al., 2016). IBFs can be very successful when they find unique and high-quality niche products or services, locally situated. Among the various advantages, such as being able to produce at a lower scale, niches reduce dependency on external markets and associated volatilities.

Authors such as Kurecic, Luburic, and Kozina (2017) manifest that niche successes are related with companies willing to innovate, for which they require CEOs with the right academic background. Furthermore, executives with Business Administration, Finance, Accounting, or Economics academic backgrounds may consider an array of other strategic options before deciding on IE. The foregoing is consistent with both upper echelons theory and social network theory, where an important characteristic of CEOs that promotes profitability is their connectedness. They may maintain key relationships and take advantage of these networks that provide valuable information and knowledge to help them predict domestic market developments, which allow faster and less expensive actions and increase strategic flexibility. This finding supports Hypothesis 3: CEOs of IBFs that majored in Business Administration, Economics, Finance, Accounting or related fields reduce the odds for international entrepreneurship.

On the other hand CEOs’ Academic Achievement (AA) and International Exposure (IX), as well as Firm Size (FS), positively relate with the odds of International Entrepreneurship. IE is by nature a complex strategy and its implementation requires advanced skills and training (Allahar & Brathwaite, 2017). Therefore, those companies whose CEOs have graduate studies are more likely to venture into this type of project (Hsu et al., 2013). This finding supports Hypothesis 4: CEOs of IBFs who have completed graduate studies increase the odds for international entrepreneurship. Likewise, it is common on the islands for people to seek high academic training abroad, where there are more options for this type of education. According to the data, 85% of CEOs with graduate studies attained their degrees at foreign universities. This favors the knowledge of international markets as well as the establishment of global networks that can eventually be exploited for international entrepreneurship (Bai et al., 2018). IX is clearly a means for CEOs of IBFs to gain international experiences and attitudes, which they will eventually bring to the islands’ business environment. In fact, IX increases the probability of having subsidiaries or branches abroad by 16%. This provides evidence for Hypothesis 1: The odds for international entrepreneurship in IBFs are higher when CEOs have studied in foreign universities.

Finally, studies in general show that the size of companies is positively related to the extent of their internationalization. The limited resources of relatively smaller companies and their lower capacities to take advantage of economies of scale are some of the reasons why larger companies have a greater tendency towards internationalization (Ruzzier & Ruzzier, 2015). According to the results, when firm size increases by 1 unit, the probability of IE rises 5%.

5. Conclusions

Endeavoring internationally is a process that requires keen insight and direction, and is critically impacted by the CEOs and their particular characteristics. In addition, executives operating in IBFs face different environmental vulnerabilities and also advantages, which influence their decisions regarding IE. By studying these overlooked agents this paper informs the scholarly community, responding to the need for more diversity. This study covered 164 island-based firms listed in securities exchanges across eight small islands in the Caribbean, Europe, Africa, and Oceania: 40% of which had foreign subsidiaries or branches. This paper provides evidence in support of upper echelons theory and invites the extension of social network theory, taking into account the unstudied geographical context of the islands and islandness.

Education plays an important role in the foreign business endeavors that CEOs of IBFs set for their companies. When CEOs have graduate studies and have been trained abroad, a favorable effect is observed on the probability of IE. Instead, CEOs majoring in Business Administration, Finance, Accounting, or Economics seem to discourage IE. Other CEO characteristics such as tenure and family allegiance were found to be unfavorable for IE of IBFs operating in small islands.

While the general consensus states that backgrounds in Business Administration, Finance, Accounting, or Economics equip CEOs with tools that can contribute to the IE endeavors of the firms they lead, this study provides evidence of the contrary. This can be explained through islandness; due to risk aversion organizations operating in markets that are isolated are more likely to adapt to local market conditions, innovate, and specialize (exerting strategic flexibility), rather than to seek growth abroad through operation of a subsidiary or branch. The success of these companies depends on their positioning in the local market and the ability of their CEOs to take advantage of the information and knowledge sharing from their networks. CEOs with Business Administration, Finance, Accounting, or Economics backgrounds are better prepared to process this information and make adequate decisions that increase strategic flexibility, allowing the companies they lead to avoid IE.

This research opens the way for more investigation regarding IE at IBFs. It is clear that the particular context of the islands contributes to the international literature beyond a new case study. Future research could address this topic including other executives (such as CFOs) and members of IBFs’ boards of directors. The sample could also be expanded to include IBFs based on islands of various sizes, as well as other CEO attributes such as gender. Delving deeper into specific island industries such as hospitality and tourism, banking and financial industry, may also provide for better understanding of IE at IBFs.