Introduction

Governance can be understood as an umbrella term for arrangements that regulate, manage, and guard the range of activities in a system allowing it to respond to any issues, disruptions, or circumstances from both internal and external origins (Bramwell & Lane, 2011; Charlie et al., 2012; Cole & Browne, 2015; Hall, 2011; Heslinga et al., 2017, 2019; Parra & Moulaert, 2016; Partelow & Nelson, 2020; Sharpley & Ussi, 2012). As Stoker (2018) states, “the value of the governance perspective rests in its capacity to provide a framework for understanding changing processes of governing” (p. 18). Different forms of governance exist, from hierarchical, market-driven, networking-based, and egalitarian to mutual-aid governance (Moulaert et al., 2022). Governance has long been of interest to academia and has recently become a central concept in the field of tourism on small islands. Governance is important in the literature on islands (tourism) to address the unique challenges and opportunities faced by island communities regarding the islandness of islands (Baldacchino, 2007).

Small islands are typically distinguished by their modest land mass, although their measurements are contextual to the region or country under consideration. Apart from their small size, small islands have unique characteristics due to their isolation and susceptibility to external factors, which contribute to the notion of islandness and influence the lives and sense of self of island communities (Baldacchino, 2004). Those islandness characteristics undoubtedly influence the building of alternative governance in islands as one kind of resource-deficient situation (Warrington & Milne, 2018). It creates both opportunities and challenges for islands, influencing how they interact with the rest of the world. Tailored approaches to governance and development are required to address these unique challenges and opportunities faced by island communities (Baldacchino, 2007). Moreover, governance is still to be further understood in realising sustainability in the realm of island tourism to guarantee local development that offers benefits in social, economic, and environmental aspects in an impartial manner.

Many scholars have studied Small Island Developing States (SIDS), often related to the tourism field, with exemplary case studies on Malta, Bahamas, Mauritius, the Caribbean, the Pacific islands, the Solomon Islands, Fiji Islands, and many others. Small islands that become tourist destinations, particularly for (community-based) ecotourism, have advantages but also many limitations. Community-based ecotourism involves local communities in the planning, development, and management of tourism activities (Honey, 2008), aiming to create positive social, economic, and environmental impacts (Weaver, 2001) while preserving the destination’s cultural heritage and natural resources (Fennell, 2014). Aside from the lack of local government capacity, they are dependent on the richness of their natural resources, which leads to uncontrolled tourism development threatening these resources and environmental degradation. There is also the imminent danger of diminishing touristic attractiveness, which might be triggered by the inhabitants as the human resources for developing community-based ecotourism, but who might be poorly educated and have limited environmental awareness (Apostolopoulos & Gayle, 2002; Baldacchino, 2018; Weaver, 2006; Williams & Ponsford, 2009). The paradise-like natural beauty on islands can be capitalised on to increase their competitiveness (especially economically) by exploring this resource. However, in the islands’ local development, inadequate community-based ecotourism planning and governance, and unsustainable tourism practices pose a threat to the long-term viability of community-based ecotourism itself and impact the livelihoods of residents. To cope with those issues, we need more than just economic improvement or resource capitalisation, especially socio-political transformation and knowledge, particularly among local inhabitants.

Following capitalism’s tendency to measure everything in terms of monetary incentives, many examples exist of either the government way or the corporate way of managing tourism (development), which are generally more focused on economic benefits (Nurhasanah et al., 2017; Nurhasanah & Van den Broeck, 2022). Somehow these give an economic advantage to the local inhabitants. The question, however, is for how long? How can local inhabitants participate in planning and governing community-based ecotourism in their locality? How can they benefit from it in sustainable ways? Moreover, the local inhabitants often are the excluded ones, with little or no (political) bargaining power enabling them to be included in the decision-making regarding their own place and its local development (Hall, 1996; Sofield, 2003; Zurba et al., 2016). There is a need to build better alternative governance arrangements that address the issues of local involvement, building community capacity, social and political empowerment, and local (political) bargaining power.

As scholars began to explore aspects of governance in island tourism, various topics have been addressed, including climate change, resilience, adaptation, economy, fisheries, biodiversity, and others. However, the role of local community participation seems to be insufficiently studied. Therefore, we undertake a thorough analysis of the literature on the governance of tourism on small islands, with a special emphasis on the following questions: to what extent has alternative governance of community-based ecotourism on small islands been discussed and contested thus far in research? What are the gaps that have gone unmentioned in earlier studies conducted by a variety of scholars and schools?

Our paper is structured along a five-step process. Following this introduction, section two discusses our systematic literature review approach, essentially a mapping tool based on bibliometric data. The next section maps the literature in terms of common subjects and keywords, their dynamics, density, and network patterns. We then conduct a qualitative content analysis of selected articles to develop leads for (foci in) further research on how local communities build alternative governance arrangements on small islands. Finally, we conclude our discussion by determining the literature that helps address research gaps related to building alternative governance in the context of (community-based) ecotourism on small islands. This paper ultimately exposes several underdeveloped concepts relevant to building alternative governance structures: participation, community capacity building, (socio-political) emancipation, (political) bargaining power and social innovation. Each concept elucidates the complexity, multiplicity, and multi-scalarity aspects of governance.

Materials and methods: a systematic literature review with bibliometric and content analysis

First, we built a diverse research team, including outsiders and islanders. The diversity allowed us to relate the small islands to the larger spheres and interpret the study’s results. We used a systematic literature review to investigate existing work, look at past and current research, oversee research topics, and recommend the need for further research topics. In this case, the recommendations are expected to advance the understanding of alternative tourism governance. To conduct this research, we used Kitchenham’s systematic literature review method. The review procedure was generally conducted in four phases: a) review planning, b) performing the review, c) data extraction, d) analysis and result reporting (Kitchenham & Brereton, 2013).

The systematic literature review was based on published articles indexed by Scopus and Web of Science from their earliest year to the latest on the theme of (alternative) tourism governance on small islands. Scopus is believed to have the largest database of peer-reviewed literature and a reliable search engine to search, discover, and analyse academic publications (Bar-Ilan, 2008; Leydesdorff et al., 2010; Scopus, 2020). Another database platform is Web of Science, one of the world’s most extensive resources for citation, indexing, and citation analysis of a wide variety of scientific works in all possible scientific fields, created by Thomson Reuters (Leydesdorff et al., 2010; MEJSP, 2017).

Previously, the systematic literature review method has been used in the fields of health, software engineering, natural hazards, disaster studies, and climate change (Djalante, 2018). In the field of tourism, similar methods were also used to explore research related to the theme of sustainable tourism (Zolfani et al., 2015) as well as the topic of accurate information on tourism (Pertheban et al., 2019).

We limited our analysis to publications in the English language as the most extensively used international language on the global stage. As a result, research on niche subjects conducted by non-English authors can be underrepresented in this paper. This article also employed bibliometric methods to map literature findings, strengthen the reliability of the systematic literature review, and more clearly display the data collected in the form of maps. The bibliometric tool VOSviewer was used to generate a co-occurrence map from the gathered and filtered literature. The systematic literature review method was used for data collection to outline the research question, document selection analysis and present results. Before using the systematic literature review, authors needed to do the preparation as mentioned in the extended file. Afterwards, we searched for and selected previous studies and filtered articles related to the research themes and objectives.

Moreover, in the literature review, we also used VOSviewer tools after filtration, using database platforms. VOSviewer is a bibliometric tool that enables the clustering of publications and the aggregate analysis of the resulting clustering solutions and mapping of it (Agapito, 2020). Bibliometrics is a statistical method that may quantitatively analyse research articles concerned with the targeted particular topic using mathematical methods (Chen et al., 2014). Here, we use visualization in the VOSviewer that employs a technique known as a term map to depict the topics covered by a cluster (van Eck & Waltman, 2010, 2017, 2022). This visualization shows the most frequently occurring terms in publications belonging to a cluster and their co-occurrence interrelations.

Van Eck & Waltman (2010, 2022), the developers of this tool, explained that the VOSviewer creates an association map. It is an application that can show the co-occurrence of terms/fields related to the intended context (which is alternative tourism governance on small islands). This application may thus track the convergence of fields based on the data that has already been gathered from database search engines and the reference manager explained above. For the systematic literature review purpose in this article, we used the co-occurrence matrix table that can be displayed as a map in VOSviewer. It comprises three stages: (a) the co-occurrence matrix table is used to compare categories, (b) a two-dimensional map based on the first stage’s similarity, that is, high similarity relations are placed close together, whereas low similarity relations are placed apart, (c) parameters are clustered, and their density is determined by their frequency of occurrence (Jeong & Koo, 2016; van Eck & Waltman, 2010, 2017). The VOSviewer then produces three kinds of displays. The first is a network visualization which is frequently used to illustrate the link between concepts. It analyses clusters or groups based on the research theme. The size of the node represents the frequency with which a word occurs in bibliometric data. Second, an overlay visualization is utilised to assist researchers in annually analysing the evolution/trend of research. Third, density visualization is designed to assist in visualising the density/frequency of a researched topic (Dyer et al., 2017; van Eck & Waltman, 2017). The proper analysis will aid in identifying the novelty and originality of the proposed research.

Results

The Multistage Approach of Systematic Literature Review

Using a multistage approach in a systematic literature review, we created a database to see the extent of research related to the alternative governance of ecotourism on small islands. Only using the term “small island” in the search engines, gave 8775 publications from Scopus and 3746 publications from Web of Science so they were still too broad. Thus, we narrowed our search according to the expected themes and contexts, namely governance, participation, bargaining power, emancipation and/or social innovation that carries the context of small islands and indigenous/community-based ecotourism.

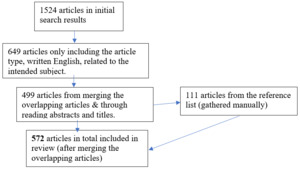

In the stages of inclusion and exclusion of publications summarized in Figure 1, stage one is clear enough to understand. The search includes publications with a timeframe from 1980 to 2021, using the terms small island, ecotourism, governance, participation, bargaining power, emancipation, and social innovation in the title (and keywords) option in the Scopus and Web of Science databases. The second stage was to exclude some articles based on the publication type, language, and subject area, which left 649 publications, 201 in Scopus and 448 in the Web of Science. Then, in stage three we merged the same articles in both of the database managers. The publications were narrowed down by excluding the overlapping articles leaving 544 publications. Then, we excluded those that did not relate or that were quite far from the authors’ intended topics, mainly those that were not concerned with the alternative governance of ecotourism on small islands or did not relate to participation, social innovation, or bargaining power on small islands. This phase was finished after reading the abstracts of the articles and left 499 publications in the database. In the fifth phase, the authors added articles that were initially found from other search engines related to the intended context and themes and that had been kept in the reference manager Mendeley. The following step was to gather all the filtered articles from Scopus and Web of Science along with the ones from Mendeley. After merging the articles, we ended up with 572 articles for analysis, looking for topic co-occurrence interrelations using the VOSviewer tools. The following section depicts the results of the bibliometric analysis from the VOSviewer.

Bibliometric mapping analysis

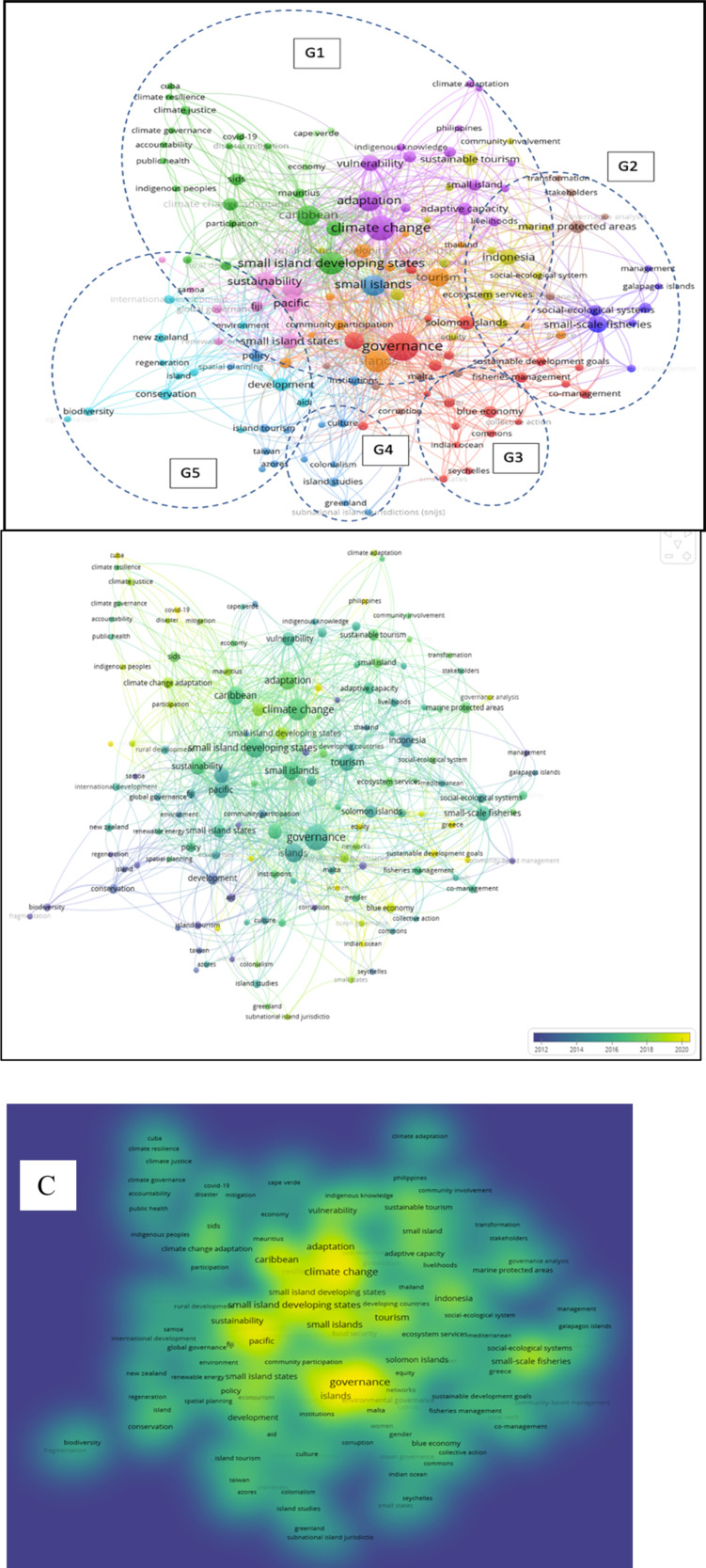

Working with 572 articles using Vosviewer software, we then decided to include a minimum of three times the appearance of a term in the database of each manuscript. From there, 141 of the 1773 keywords met the criteria (see Figure 2). Based on network mapping (see Figure 2A), we found that the most commonly occurring terms were “climate change” (total link strength 105) and “governance” (total link strength 102) both of which had a strong association with “Caribbean” and “adaptation.” A preliminary network mapping visual pictured the connections and absence of connections between different fields of research regarding the context of community-based ecotourism on small islands. In particular, we grouped the mapped bubbles based on their distribution patterns to make it easier to observe the network proximity distribution of the bubble themes. We then grouped them into five groups. The dominant area, Group 1 (G1), is focused on governance, climate change, small island developing states (SIDS), and the Caribbean. The composite areas indicate a high degree of connectivity between those fields of study. Other groups (G2-G5) of distinctly different clusters revolve around the terms small-scale fisheries, blue economy, island studies, conservation, and development.

Looking at the main area (G1), in particular, the terms Caribbean, small islands/islands, tourism, and adaptation occur predominantly around the centre of the cluster with equivalent relevance in all of the three fields of governance, climate change, and SIDS. Thus, through an in-depth reading of relevant articles common concerns for tourism, adaptation, the Caribbean and (other) small islands were expected. In comparison, the clusters for climate change (G1) and small-scale fisheries (G2) show a less coherent collection of terms pointing to different sets of priorities. In the case of climate change (G1), the most readily detected terms are small island developing states, small islands, tourism, and adaptation. These terms are located at a distance from the terms governance, community participation, and community involvement, suggesting that the two sets are largely unrelated in published literature and academic research.

Likewise, in the small-scale fisheries clusters (G2), the most frequently detected terms relate to socio-ecological systems, marine protected areas, fisheries management, and co-management, particularly with regard to the studies of fisheries. Many terms are located far from governance and community participation. Again, it indicates that the two sets of terms (governance and community participation) are largely unrelated in the published literature and academic research. Such an apparent limited affinity between governance and community participation or community involvement raises questions about the lack of understanding and experience in combining inclusivity with governance in the context of community-based ecotourism on small islands. Furthermore, the terms social innovation and bargaining power do not appear in the terms map, indicating that those concepts refer to an underdeveloped research area.

Finally, the composite cluster (G3) related to blue economy issues, represents an underdeveloped area of research as well prioritising commons, gender, and collective action. The same applies to the other two groups that have a distinct network of governance or participation. G4 revolves around culture, the impact of colonialism, and jurisdiction, while the G5 cluster highlights development, conservation, and biodiversity. These groups suggest different priorities in seeing small island issues.

To further investigate the connections and trends in the period 1980-2021, we can see them through the overlay map below. We can see the trends in publications throughout the years (see Figure 2B). The trend demonstrates that today’s themes are more focused on SDGs, the blue economy, SIDS, COVID-19, and case studies in Greece. Meanwhile, issues examined regarding climate change and governance were most often debated between 2014 and 2018. We can also see discussions about ecotourism, community-based management, and community participation interested scholars from approximately the year 2012 (and before that until around 2014. These themes trended in that period. Additionally, as indicated by the density map, the most frequently published articles discuss topics such as “climate change,” “governance,” “small island developing states,” “adaptation,” “Pacific islands,” “Caribbean,” and “sustainability,” followed by “tourism,” “resilience,” “vulnerability,” “small scale fisheries,” and “socio-ecological system” (see Figure 2C).

Moreover, for other issues, there is a great deal of opportunity to add to the rich literature, particularly when discussing themes related to building alternative governance for community-based ecotourism on small islands. Figure 2C demonstrates that, although the governance theme has been extensively utilised, its link with the themes of institutions, community participation, (spatial) planning, community involvement, collective action, and in relationship to Indonesian has not been well studied. As the largest archipelagic country with nearly 17,000 small islands, Indonesia is an important case to study island governance and local development. Using various viewpoints, traditions and methods, addressing these topics can be one of the building blocks for bridging the gap between small island literature, governance, and tourism planning studies.

If we look more deeply into the network mapping, we can see that the articles which have used the small island context have mostly raised the theme of climate change, with a correlation to topics exploring more about governance, SIDS, tourism, (climate change) adaptation, vulnerability, and sustainability. Other topics are widely spread including economy, fisheries, MPA, culture, finance, and many more as can be seen in Figure 2. The bibliometric study of the existing articles so far shows that the term “climate change,” as the most common theme, is typically associated with a number of terms such as SIDS, Caribbean, adaptation, small islands, tourism, and governance in a bigger circle. Adaptive capacity, (case study) Thailand, livelihood, marine protected area, and local knowledge are in a slightly smaller circle. Unfortunately, these topics did not address the interplay between governance, the role played by the actors involved, and their impact on policymaking. Multi-scalarity is pertinent in the governance setup (Moulaert et al., 2022), while not only practicable technical insight is necessary but also a process that leads to durability.

The second most common keyword related to other topics in this small island theme is governance. This topic has become one of the most common trends in the discussion of small islands, correlated with topics that also discuss climate change. Slightly different from the climate change network, governance raised in the context of small islands is also related to other discussions that have little occurrence, namely small-scale fisheries, SDGs, co-management, collective action, ecotourism, institutions, community participation, and others (see Figure 3).

If we zoom in on the network mapping of the SIDS theme, we can see that many authors highlighted their research on small island developing states. They raised the topic of SIDS as a trend of discussion during the last few years (from around 2016 until now), especially around the topic of climate change (adaptation, vulnerability, and adaptive capacity), governance, and tourism. This was followed by some case studies mostly from the Caribbean, Pacific (islands), Solomon, Mauritius, Cuba, and Caricom. There are also case study articles that focus more on certain cases, such as those in the Caribbean (Grydehøj & Kelman, 2020; Oviedo-García et al., 2019; Peterson, 2020; Sridhar et al., 2020; Trejos & Chiang, 2009), the Mediterranean (Boukas & Ziakas, 2016; Cassar et al., 2013; Chaperon & Bramwell, 2013; Maroudas & Kyriakaki, 2001), and the Pacific (Barragan-Paladines & Chuenpagdee, 2017; Farrelly, 2011; González et al., 2008; Pazmiño et al., 2018). In the network mapping, shown in Figure 3, the term “governance” is linked to a number of terms from within and other clusters, including food security, Caricom, rural development, Fiji, and community participation in small circles. The larger circles sequentially linked closer to it are climate change, Caribbean, tourism, and Pacific/Pacific islands.

We further noticed that there are still very few case studies in the South Pacific region, especially in Asian countries. Only a few were caught in the bibliometric filter, namely cases in Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia and Taiwan. We highlighted the occurrence of Indonesian cases, which is within the network’s main area (see figure 2A). (Sustainable) tourism, islands, small-scale fisheries, social-ecological systems, fisheries management, and a few on the topic of community involvement and planning make up a minor portion of Indonesia-related research (see figure 2A). These areas of study are however not a priority so far and not a current emphasis. With regard to the network of climate change and governance topics, Indonesia is distanced from these two trending topics. Research about Indonesia according to the bibliometric conducted is commonly related to a number of terms like tourism, small islands, livelihood, small-scale fisheries (management), social-ecological system, water, community involvement, and a few others. So, there is still room to enrich the study on the case area, especially when we consider that Indonesia is an archipelagic nation comprised of tens of thousands of small islands with a number of lingering issues.

Contribution to further research

To answer the research objectives posed in this article, we further selected publications based on their focus on participation, capacity building and alternative governance in ecotourism on small islands. To this end, we filtered the 572 scientific papers that were regarded as highly relevant to our research. In the database, there are 138 articles that emphasise tourism on small islands. However, after manual screening by carefully reading the titles and abstracts of articles, only 22 publications appeared to have significant links with the themes that we wanted to investigate (community participation, governance, emancipation, (political) bargaining power, and social innovation) in the context of community-based ecotourism on small islands. We now move forward to define the areas to be studied in future studies.

Unpacking participation in small island tourism

The authors of the 22 most relevant articles make the important point that there is a growing body of tourism literature on collaborative governance and community involvement (Charlie et al., 2012; D’hauteserre, 2016; Dickson et al., 2017; Farrelly, 2011; Maroudas & Kyriakaki, 2001; Oviedo-García et al., 2019; Phelan et al., 2020; Ziegler et al., 2021; Zurba & Papadopoulos, 2021). More academics now acknowledge that (indigenous) communities are not merely affected by tourism (activities), but actively react to it (Long & Wall, 1995; as cited in Telfer & Sharpley, 2007). In the context of small islands and ecotourism, a growing body of research suggests that participation is one of the suggested possibilities for improving the governance system, notwithstanding the complexity and difficulty of the issue. Farrelly (2011), for example, emphasised Murphy’s (1985) claim that the viability of tourism development is dependent on community involvement. In practical terms, this implies that the role of local communities in tourism planning is crucial for co-creating (Agius & Samantha, 2023) and redesigning the tourism product of island destinations (Boukas & Ziakas, 2016). Moulaert et al. emphasise that “communities are often the protagonist of solidarity ethics and act as a lever to re-balance individualism and collectivism” (2022, p. 4). Hence, their involvement in tourism, development, and decision-making is imperative.

Another scholar concurred that community involvement and empowerment are essential for small island development, implying the need for active participation and capacity building beyond mere financial support (Armitage et al., 2009; D’hauteserre, 2016; McLeod & Airey, 2007; Ziegler et al., 2021; Zurba & Papadopoulos, 2021). For instance, enhanced capacity for participation in governance forums necessitates assistance in overcoming barriers such as language, process exhaustion, and insufficient information (e.g., briefing materials in the appropriate language and accessible format) shared prior to participation (Zurba et al., 2016). Local knowledge developed and utilised through ecotourism is a crucial development resource for marginalised communities (Walter, 2009). Ziegler (2021) argues that participation in tourism resulted in major positive changes in the beliefs and behaviours of local operators toward environment conservation, bolstering the rationale presented previously. Unfortunately, they did not provide a comprehensive study of the extent of the necessity, the process, or the community’s active participation and involvement in the capacity-building practice overall.

Furthermore, we concur with what McLeod and Airey (2007) noted in their case study of Trinidad and Tobago, namely that the long-term goal of tourism should be centred on people. It should not eliminate the relationship of symbiotic mutualism with nature, but rather optimise performance that makes use of the active engagement of the actors involved, particularly those immediately affected by the existence of tourism practices, the local population. For the sake of sustainability goals, the implementation of sustainability in (eco)tourism is contingent upon the gradual integration of new routines by locals, their motivation for capacity building, and their desire to participate (D’hauteserre, 2016). D’hauteserre (2016) noted that ecotourism would diversify the economy and increase revenue, provided it has adequate support, and preserves the culture and nature, and thus remains appealing. It is also stated that in order to achieve long-term sustainability of tourism-related objectives, community capacity building must include social and political empowerment, in addition to environmental and economic empowerment (Farrelly, 2011; Hall, 1996; Pazmiño et al., 2018; Sofield, 2003). These activities should not be viewed as a result, but rather as part of the development process.

In line with the explanation above, Moulaert et al. (2013) argue about the debate on sustainable (development) and social innovation. While sustainable (development) paves the way for technological, economic, and ecological innovations, it may also lead to socially conceived innovations and cautions against ignoring the societal impacts of poorly conceived technical solutions. Social innovation can aid in comprehending, illustrating, and materialising collective action for sustainable development. Thus, there is a need to ensure multi-actor involvement through inclusive practices and participation.

Community participation and small island development

Analyses of 22 papers on community-based ecotourism in small islands indicate that the ultimate objective of sustainability is not only economic but also environmental and social (Farrelly, 2011; Grydehøj & Kelman, 2017; Kelman, 2021; Phelan et al., 2020; Praptiwi et al., 2021). Given the islandness characteristics inherent to each small island, environmental protection is an urgent issue that must be managed in tandem with the growth of tourism destinations. We stress small island development as a form of local development that requires a different approach than other spatial developments since the islandness characteristics place it in a resource-deficient situation. Thus, both policy and the development agenda are expected not to simply shout “sustainability” as a shield to pave the way for ecotourism projects. The case of Gozo suggests that a policy to develop an eco-island (EcoGozo) can fail due to a lack of community involvement and weak island governance structures (Gauci, 2011). Such a case underlies Grydehoj and Kelman (2017) coining the term “conspicuous sustainability” to describe the habit of engaging in activities that appear to assist sustainability, although their actual contribution to sustainability is negligible. They contend that eco-islands are ineffective at promoting wider sustainable development. In contrast, island communities can fall into the ‘eco-island trap’. To retain an illusory eco-island identity for the sake of ecotourism, the government may invest in inefficient or useless renewable energy and sustainability programmes. Grydehoj and Kelman (2017) believe that island communities should aim for a locally contextualised development, maybe centred on climate change adaptation, rather than an eco-island status oriented toward place branding and ecotourism. On the basis of these observations, we capture the significance of local contextual development as a prerequisite for achieving sustainability objectives.

Other articles emphasise the importance of focusing on the social development of the island community. Without going into detail on social issues, Ziegler (2021) suggests that economic and social benefits can be derived from community engagement in conservation projects, which will lead to pro-conservation behaviour. In addition, social value encompasses the discussion of the participation and capacity of marginalised communities in political/decision-making processes. Farrelly (2011) emphasises the necessity of refocusing development research on indigenous decision-making systems in which power and leadership structures influence decision-making processes. In his article, he also argues that poor knowledge prohibits local populations from expressing their objectives. According to the notion of bargaining power (Coff, 1999; Schmitz, 2013; Yan & Gray, 1994), local communities require a strong negotiating position in the policy-making forum to influence decisions regarding the benefits of their own island. Undeniably, a multi-layered governance system also necessitates a strong bargaining position of the typically excluded actors and the ability to participate in the central-periphery relationship with regard to decision-making, so that their voices can be heard and influenced. Few have, however, examined in detail how and to what extent local communities might acquire the skills and information necessary to participate in multilevel decision-making from the local to the upper levels.

Concerning (community-based) ecotourism, several scholars have emphasised or inferred the significance of effective governance in managing small island development, including one that leads to tourism development. As Sharpley (2012) discovered in Zanzibar, patronage and political meddling contributed to the failure of governance in island tourism. This is because poor or inefficient governance might represent an extra-institutional obstacle to fostering socio-economic development and progress. One of the points noted is to not exclude the community from tourism. The engagement of local requirements in the planning is expected to minimise the appearance of conflict within local communities and to facilitate the assumption of initiatives, hence the contribution of local communities is a vital aspect of ecotourism projects (Maroudas & Kyriakaki, 2001).

Participation-related capacity constraints also have a large impact on governance processes. The participation of local communities in decision-making and policy formulation is largely contingent on a lack of knowledge, information asymmetry, and the absence of networks (Zurba & Papadopoulos, 2021). The participation of local people as actors, substantially exposed to both the pleasant and harmful impacts of development activities on small islands, is essential. To date, scholars and schools have reiterated the necessity for local communities to be involved in decision-making as one of the agents of development not allowing them to be mere spectators for decisions pertaining to their living area. Pazmino (2018) concludes in his paper that, from the perspective of policy integration, community participation determines the effectiveness and efficiency with which policies are formulated, implemented, monitored, and evaluated, in addition to there being an urgent need to improve local technical and organisational capacities. Boukas and Ziakas (2016) highlight the need of bottom-up decision-making that must be enabled by empowering local individuals to participate in tourism planning in order to improve their quality of life. Here, he added, tourism is viewed as a result of the kind of development that locals desire to enhance their quality of life.

In terms of decision-making, Hall (1996) and Sofield (2003) note that questions of power and institutional constraints limit the extent to which local communities can participate in tourism projects in general. It has also been stated that the lack of involvement of parties with a vested interest affects these groups’ reluctance to accept the ensuing designations and comply with new restrictions (Barragan-Paladines & Chuenpagdee, 2017). Therefore, the participation of all engaged agents is essential. There is evidence that bridging organisations plays the role of knowledge brokers, coordinating cooperation, enhancing trust, and managing conflict among dissatisfied groups, so the term ‘bridging organisations’ should be used when they are significant actors in governance systems where better participation is needed (Tengö et al., 2017). In accordance with the concepts explored in the preceding section, capacity building is required in addition to empowering the local community’s negotiating power in political elements in order to modify their customs as a marginalised group within the area of small island tourism governance.

For community-based ecotourism to be successful, it is necessary to comprehend that decisions are made in a specific socio-cultural environment, social values play a significant role in local decision-making structures and processes, and it is less about resources and more about social structures and behaviours associated with resources (Farrelly, 2011; Jentoft et al., 1998). In a separate piece, Charlie (2012) investigated how collaborative environmental governance networks function in the context of tourism development on small islands in developing nations. Environmental protection is a crucial responsibility in small island tourism destinations in developing nations, necessitating collaboration among stakeholders through the development of networks and a shared understanding to foster collaboration (Ladkin & Bertramini, 2002; Svensson et al., 2006). Similarly, the selected articles concur that collaborative governance is one of the necessary components for controlling small island tourism (Charlie et al., 2012, 2013; Maroudas & Kyriakaki, 2001; Oviedo-García et al., 2019; Phelan et al., 2020; Sharpley & Ussi, 2012).

Building bottom-linked governance through social innovation

In light of the perspectives mentioned above, social innovation as a separate concept is of particular interest to dig deeper into community initiatives in creating and protecting the environment. Social innovation is not a new concept in the social sciences literature, given the fact that it was picked up in the early 1980s and has since gained prominence (Baker & Mehmood, 2013; Moulaert et al., 2007). Social innovation advocates a more sustainable approach to development by focusing on innovation at the grassroots level, no longer focusing exclusively on economic prosperity but co-creating it by offering dialogues and issuing solutions (Baker & Mehmood, 2013). This is covered by the three-dimensional objective of the social innovation school established by Moulaert and his colleagues highlighting that social innovation is about “a combination of need satisfaction through collective action, inclusive social relations, and political empowerment leading to deep democracy as a ‘new’ lens on human development at the community or local level, but with links to social change at the supra-local level” (Moulaert, 2020). In accordance with the spirit of ecotourism (in particular community-based ecotourism - CBE) which also promotes co-creation (Agius & Samantha, 2023), the SI concept teaches us how processes are valued regarding the active participation and decision-making power of local communities in all stages of tourism development, allowing them to have a sense of ownership and engage in control over their resources, with the ultimate goal of sustainable local development. In the framework of power relations, social innovation emphasises the emancipation of local communities and solidarity-based communication to create places for mutual understanding. Through its three-dimensional objective, social innovation should combat social exclusion and strengthen social ties in order to determine future activities relating to sustainable development. This, in turn, has consequences for the types of bottom-linked governance systems that enable the dissemination of social innovations across scales most effectively.

The examination of multi-level governance dynamics demonstrates that effective dynamics are rarely bottom-up or top-down. Instead, they both determine the outcome of and contribute to shaping dynamic forms of conflict and collaboration between civil society and authority at multiple scales (Moulaert et al., 2022). One concrete illustration is our own study on the transformation of the once-obscure Indonesian island, Pahawang, into a popular tourist destination. Our analysis implies that new genres of collaboration between bottom-up organisations working for environmental preservation on the small island and later seeking alternate sources of revenue for the inhabitants have significantly impacted the ways the authorities handled their quests. Collectively, they have established new organisations and partnerships to protect mangrove forests while implementing community-based ecotourism as an alternative economic stimulant, particularly for island inhabitants (Nurhasanah & Van den Broeck, 2022).

The discussion of bottom-linked initiatives and bottom-linked governance highlights the significance of experience, the process for triggering not only social but also political change. It values the process of and struggles for collaboration, dealing with disputes, negotiating with one another, participation, local initiative, dialectical bargaining with upper levels, and multi-scalar authority(s) (Moulaert, 2022). Bottom-linked governance emerges out of such socio-political experience.

By offering a new discussion in this field, the literature on small islands needs a comprehensive examination of bottom-linked governance that prioritises collaborative and inclusive governance from a multi-actor and multi-scalar perspective. This alternative governance paradigm can help bridge the gaps caused by governance constraints in geographically disadvantaged and resource-deficient regions, such as small islands.

Conclusion

This article illuminates the current situation of the literature on alternative governance of small island ecotourism. Bibliometric methods help to mathematically map some of the trends so far. Overall, it can be observed that climate change and its governance have dominated the discussion of small island settings to date. Since the 1980s, an increasing number of scholars have discussed climate change, its governance, and its relationship to tourism and fishing. Other discussions concern fisheries management, energy, and biodiversity. Academic circles thus have produced a wealth of literature in the context of (small) islands, highlighting the economy, culture, social life, technology, environment, disaster, climate change, and governance through a variety of theories, approaches, and locations.

The governance of (community-based) ecotourism has, however, not been addressed in great detail. Theoretical gaps exist in debates about the governance of ecotourism on small islands. Community participation, capacity building, emancipation, bargaining power and social innovation have received insufficient attention. Only 22 of the 572 analysed articles discuss participation, empowerment, community involvement and/or governance in the setting of (community-based) ecotourism on small islands in the given range of time. The two most common themes found in those articles are related to the socialisation of responsibility for nature conservation and sustainability issues, in addition to a nuanced exploration of the concept of governance with an emphasis on community involvement/empowerment, which, however, does not receive sufficient in-depth attention in the discussion. Few authors focus on how alternative governance arrangements are built, beginning with collective action at the grassroots level, in the face of social-political dynamics, particularly in the Global South.

Therefore, we offer a relatively new application of the school of SI as explained by Moulaert et al. (2013; 2019) to add to the existing repertoire of knowledge. The breath and spirit carried by bottom-linked governance and SI initiatives within local communities are the key to unlocking socio-political transformation. SI can also be seen as a method to creatively transform the civil society-authority relationship and make it more sociopolitically effective, which may serve as the panacea for the critically needed sociopolitical change of true democracy (Moulaert, 2022). Further research on socially innovative bottom-linked governance arrangements and the role of capacity building, emancipation, and (political) bargaining power as fuel toward people-centred SI is needed. Future research is expected to complement the research on the governance of (community-based) ecotourism on small islands.

Based on the preceding discussion, we orient our suggestions for future research by wrapping up some essential elements. In addition to environmental and economic empowerment, it is argued that community capacity development should encompass social and political empowerment. Existing literature has not, however, provided a comprehensive study of the scope of community necessities, processes, or active participation and engagement in capacity-building practises as a whole. Questions of power and institutional constraints limit the extent to which local communities can participate in tourism projects in general. In the meantime, it is essential to empower and involve local communities in tourism, development, and decision-making. Moving beyond community (capacity) building, an essential aspect in facing (socio-political) dynamics is the ability to involve multiple actors at multiple scales, rather than stopping on the bottom level. In order to assure bottom-linked multi-actor engagement, inclusive practises and active participation are required in the building of alternative governance arrangements in resource-deficient situations like small islands.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on this work. We are also grateful to Lembaga Pengelolaan Dana Pendidikan (LPDP), S-2323/LPDP.4/2022, for the overall support.