Introduction

Background of the study and Jeju Island

The territories of South Korea include the southern part of the Korean peninsula and almost 3,500 islands, including Jeju Island, the largest island between the Korean peninsula and Japan. According to the latest report from the Korea Data Industry Promotion Agency and the Ministry of Science and Technology Information and Communication, in 2020, 674,653 people lived in Jeju, and the average age of residents was 56.8 years (Jeju, 2022). Although the population of Jeju is not low for an island province, only 121,942 people are active workers (about 18%). There are five main industries listed in Jeju: health and social welfare services (15.8%), accommodation and restaurant business (12%), construction (11.6%), wholesale and retail (11.2%), and arts, sports, and leisure services (6.4%). The statistics indicate that because of the high number of senior citizens in Jeju, as in many rural communities, many of the active workforce labor in the health and social welfare services to meet the needs of the retirees (E. Hwang et al., 2014). As there are few other career and business opportunities, many active workers, families, university students, and professionals move to the mainland Korean peninsula, particularly to the capital city of Seoul, for more options (Dos Santos, 2022; Kang & Kim, 2017).

Collectivism and Confucianism are traditional in East Asian belief, thinking, and practice, and play significant roles in Korean social and cultural life (Han, 2017; Im, 2019). The belief of 신토불이(身土不二) or Shintubuyi, translated as “You only need food from your place of origin,” is a traditional belief that Korean people should stay in their place of origin during their lifespan to respect their motherland (He & Zhu, 2022). Consequently, many family and clan-based associations have been established in different areas and cities of South Korea to connect the diaspora from different regions, particularly residents from rural communities who have moved to the metropolitan regions for economic and personal development (Yim et al., 2022).

Although South Korean people speak the Korean language as their native language, dialects, accents, and unique vocabulary are not uncommon based on geographic locations, family clans, social classes, genders, beliefs, and economic backgrounds (Yang, O’Grady, et al., 2019). Due to the island’s isolation, the people of Jeju have developed their own language structures, sociocultural backgrounds, beliefs, and religious practice (Yang, Yang, et al., 2019), particularly in the eyes of mainland Korean people who tend not to have significant connections and businesses with the people of Jeju. A lack of interaction with their mainland Korean counterparts led the people of Jeju to develop their own living styles, understanding, and beliefs, which has driven their self-efficacy and social identity as Koreans, people of Jeju, or alternatives (E. Hwang et al., 2014).

The South Korean government does not limit the movement of South Korean citizens and residents within the territories. Without limits, individuals and groups tend to move to the capital city of Seoul from locations throughout the country to pursue various opportunities, such as education and career development. Although Jeju Island is known for its tourism and hospitality industry, the people of Jeju move to Seoul and other cities in the mainland Korean peninsula to pursue greater opportunities and are attracted by city life. However, previous studies (Heo & Lee, 2018; O’Grady et al., 2022; Song, 2018; Yang, Yang, et al., 2019) indicated that the people of Jeju have their own living styles, understanding, and beliefs that have categorized their identity apart from those from mainland Korean. As only a few studies focus on this problem, this study may fill the research and practice gaps in this area based on the employment of theories of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997) and social identity (Tajfel, 1969; Tajfel & Turner, 1986, 1979). The following section explains the purpose of this study.

Purpose of the study and research questions

As mentioned, South Korean people speak the same Korean language. However, due to the island’s isolation, the people of Jeju speak their own language and develop their own cultural practices. Previous literature (Heo & Lee, 2018; O’Grady et al., 2022; Song, 2018; Yang, Yang, et al., 2019) indicates that the people of Jeju have their own living styles, understanding, and beliefs that have categorized their identity as distinct from their mainland Korean counterparts. However, how the people of Jeju describe their social identity and challenges due to their unique Jeju dialects and sociocultural practices remains unclear. Therefore, it is important to have studies to uncover these issues and the problems faced by the people of Jeju.

This study aims to investigate the self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997) and social identity (Tajfel, 1969; Tajfel & Turner, 1986, 1979) of a group of people of Jeju who have come to the mainland Korean peninsula for their university education. The research was guided by two research questions:

-

How do the people of Jeju describe their social identity in the mainland Korean peninsula, particularly as university students in South Korean university environments?

-

How do the people of Jeju describe their challenges and problems due to their unique Jeju dialects and sociocultural practices, particularly as university students in South Korean university environments?

Significance of the study

Based on the statistics from the Korea Data Industry Promotion Agency and the Ministry of Science and Technology Information and Communication (Jeju, 2022), only 18% of the current Jeju residents are active in the workforce. Many young and mid-aged adults decided to leave the island due to the lack of career opportunities and educational pathways. In fact, no official statistics indicated university student enrollment based on their place of origin (i.e., province), as South Koreans can live in all provinces without any restrictions. However, due to the career opportunities and orientations, many active workers decide to go to the mainland for better career options, particularly those not interested in the tourism industry (Dos Santos, 2022; S.-P. Kim, 2020). The people of Jeju that move to the mainland Korean peninsula may face challenges in their self-identity, self-efficacy, and personal backgrounds as their sociocultural development and customs, such as language, may not be the same as their mainland counterparts (O’Grady et al., 2022; Yang, Yang, et al., 2019).

Due to the Kuroshio Current and unique location, Jeju has developed its own sociocultural development, traditional practices, business industry, local customs, religion, and even language (i.e. dialect), which are not similar to the communities in the Korean peninsula (Heo & Lee, 2018). Although Chinese cultures and customs significantly impacted Korean communities, Jeju has its own mixed cultures and practices due to its unique position (Song, 2018; Yoo, 2018). Due to Jeju’s geographic location, the people of Jeju continue to have their own unique sociocultural practices and customs. As people of Jeju can stay, work, study, and access benefits and services on the mainland, people of Jeju with unique cultural characteristics may experience challenges due to their backgrounds, such as social identity, dialects, and sociocultural practices, particularly young adults who are studying at universities. Therefore, it is important to understand how Jeju’s islandness impacts and influences the social identity of the people of Jeju.

Literature review

Social identity theory

Social identity theory (Tajfel, 1969; Tajfel & Turner, 1986, 1979) has been used to investigate the sense-making processes and the understanding of individuals and groups, particularly in terms of how groups of people describe their in-group and out-group beliefs, behaviors, and understanding. Internal and external factors such as social class, place of origin, nationality, language, sexual orientation, status, religious practice, and belief (Dwertmann & Kunze, 2021; Erisen, 2017; Gibbs & Griffin, 2013; Mullin et al., 2018) are some of the elements that categorize people’s backgrounds and identities (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Although people may grow up in the same community and region, different factors and elements may affect their connections and social identities, particularly in creating ideas of we, them, us, and you (Erisen, 2017; Tong et al., 1999). According to Adams & van de Vijver (2017), people’s and individuals’ identities can be categorized into three levels: personal identity (e.g., values, goals, achievements), relational identity (e.g., occupation, position in the family), and social identity (e.g., nationality, ethnicity). This study focused on social identity, which concerned external, community-level, and social-level identities, therefore, social identity theory (Tajfel, 1969; Tajfel & Turner, 1986, 1979) is appropriate.

In the current study, although the people of Jeju are South Korean citizens who receive the same education as mainland Koreans, the language, sociocultural perspectives, economic background, and place of origin are not the same as their mainland counterparts, which impacts their social identity as South Korean people. By using this theory, the researchers wanted to understand how these elements impact the social identity of a group of people of Jeju, particularly based on the perspective of university students (Mantai, 2019; Nomnian, 2018).

Self-efficacy theory

Self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997) refers to the beliefs of individuals and groups in their capacity and ability to conduct a series of actions, behaviors, and ideas to meet their goals and expected achievements. Motivations, behaviors, and external environmental factors impact the beliefs and self-efficacy of individuals and groups, which connect to the likelihood of their performance completion. Individuals with a high-level of self-efficacy are more likely to achieve their final goals and ideas (Cunningham et al., 2005; Flores et al., 2008; Kwee, 2021). In social psychology, motivation and self-efficacy are usually connected as individuals’ motivations may increase their self-efficacy in a series of actions and behaviors, such as the description of their own experiences, self-esteem, and self-confidence (Blanco et al., 2020).

In this study, the researchers wanted to understand the challenges and problems due to the uniqueness of a group of people of Jeju. The literature indicates that the people of Jeju do not always share the same backgrounds as their mainland Korean counterparts due to the isolation and the island nature of their homeland (Li et al., 2021). Many internal beliefs as well as external and environmental factors, are significantly different from mainland practices (Yang, Yang, et al., 2019). Therefore, people of Jeju living in mainland Korea may have had unexpected experiences. Using self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1997), the researchers investigated the experiences, challenges, and problems of a group of people of Jeju from the perspective of university students.

Sociocultural behaviors and practices in Jeju: the differences between the mainland and Jeju

After the Korean War (1950-1953), South Korea experienced five phases of political movements: Illiberal Democracy (1945-1960), Democratic Authoritarianism (1961-1972), Authoritarian Exceptionalism (1972-1987), Democratic Paternalism (1987-2001), and Participatory Democracy (2002-present) (Nilsson-Wright, 2022). Although South Korea has experienced political movements that have changed its sociocultural and economic development, most development has tended to contribute resources and energy to the metropolitan regions and provinces close to the capital city. This has led to Jeju continuing to have its own sociocultural understanding and perspectives (Song, 2018). In other words, due to the geographic location and islandness of Jeju, development within the mainland Korean peninsula did not play significant roles in its sociocultural development and customs. Therefore, many people of Jeju continued to exercise their sociocultural practices and self-identity based on their own customs and language development (O’Grady et al., 2022; Yang, Yang, et al., 2019).

Currently, South Korea has 17 administrative divisions, made up of six metropolitan cities (Gwangyeoksi 광역시/廣域市), one special city (Teukbyeolsi 특별시/特別市), one special self-governing city (Teukbyeol-jachisi 특별자치시/特別自治市), and nine provinces (Do 도/道) with one special self-governing province (Teukbyeol Jackido 특별자치도/特別自治道). Although the central government office governs all these divisions, the geographic locations significantly divide the backgrounds and sociocultural perspectives of the local residents. After the Korean War (1950-1953), the South Korean economy was destroyed by political unrest. Following the Miracle on the Han River (한강의 기적/漢江奇蹟), between 1953 and 1996, many provinces and cities developed rapidly, particularly those connected to the railway network (Howe, 2020). However, Jeju is an isolated island without rail connections and the central government did not allocate significant resources to its development (Robinson, 1994). Although the government sponsored tourism projects as early as the post-war years during the mid-20th century, the overall level was limited.

Due to its economic status and geographic isolation, Jeju did not experience industrialization, technology, urbanization, and internationalization. In addition to the challenges of the past few decades, the island of Jeju’s isolation led the people of Jeju to develop their own living styles, spoken language, sociocultural perspectives, and behaviors (Chung et al., 2011). People from mainland Korea may stigmatize and discriminate against people of Jeju due to their differences, social identity, and sense of collectivism. As a result, the people and the industry of Jeju have developed their own pathways through tourism and small businesses (Dos Santos, 2022). As the central government does not contribute many resources (S.-P. Kim, 2020; Song, 2018) to the educational system, many local residents continue with their own language and sociocultural practices without significant interruption from the mainland.

The uniqueness of Jeju due to its isolation and islandness: the development of self-identity

Besides the technological, financial, and industrial gaps in investments from the central government in Seoul, the sociocultural differences between the mainland and Jeju are also significant (S.-P. Kim, 2020; Song, 2018; Yang, Yang, et al., 2019). The educational and daily language is Korean, and the population speaking the Jeju dialect continued to decrease (Yang, Yang, et al., 2019). Moreover, after the Korean War, the central government encouraged and finalized the educational curriculum for all schools in South Korea. Many students experienced and received their education in standardized Korean language in schools from the 1950s. The Jeju dialect remained the home language for this generation. As for the current generation (individuals who were born in the 1990s), not all can speak the Jeju dialect fluently. However, many can understand the grammatical structure and vocabulary based on conversations with their family members (S.-P. Kim, 2020; Song, 2018; Yang, Yang, et al., 2019).

A recent study (S.-P. Kim, 2020) indicated that although some governmental policies were established in the mainland Korean peninsula, the policies might not be useful in Jeju because of the uniqueness of its islandness and locations. In other words, although the central government released orders and policies nationally, the people of Jeju and local residents may not want to follow the policies and regulations as Jeju has its own sociocultural background and development (Heo & Lee, 2018; Li et al., 2021). Therefore, self-identity and the uniqueness of the people of Jeju play significant roles in the sense-making processes and understanding in their daily lives.

In terms of religious practice, Christianity was adopted in South Korea during the 20th century due to the development and influence of westernized, particularly American cultural practices. Although not all South Korean people follow Christianity or other westernized religious practices, Christianity plays a significant role in South Korean communities, with about 30% of its population practicing Christianity today (Borowiec, 2017; Grisafi, 2021; Lee & Oh, 2021).

However, due to Jeju’s isolation, Shamanism (local folk religion), Buddhism, and Confucianism continue to play significant roles in the Jeju communities. The religious practices of the people on Jeju were not influenced by Christianity and many of them are proud of their unique sociocultural perspective, understanding, practices, and religion.

In addition, although the Korean Joseon dynasty (1392-1897), the Japanese colonial government (1910-1945), and the Park Chung-Hee government of the Republic of Korea (1962-1979) strongly disagreed and disapproved of the religious practices, behaviors, and activities of local folk religion, the island’s isolation prevented its cultural erasure as the central government could not control remote and rural regions (Yoo, 2018). More importantly, as traditional East Asian customs and practices such as collectivism, the local language, and religious practice continue to play significant roles in understanding, sense-making processes, and self-identity, the people of Jeju are proud of their uniqueness, particularly in the field of self-identity (E. Hwang et al., 2014; O’Grady et al., 2022; Yang, Yang, et al., 2019; Yoo, 2018).

Methodology

Research design

The general inductive approach (Thomas, 2006) was employed to collect in-depth qualitative data from a group of 16 participants. The general inductive approach was appropriate for collecting meaningful qualitative data because it is easy to use for research design and data collection. Thomas (2006) indicated that the general inductive approach could categorize raw data and materials in a summary format, create meaningful connections between the research purpose and data, and develop themes that can answer the collected materials’ research questions. Based on the recommendations, the researchers believed the general inductive approach should be the appropriate design.

Participants and recruitment

16 participants were recruited to join this study and share their ideas about their social identity and their challenges (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) as people of Jeju and their experiences in the university environments on the mainland. Only snowball sampling strategy was employed (Merriam, 2009). First, the researchers invited five participants based on personal networks at two universities on the mainland. Based on the invitation, the participants might refer other potential participants to the study who met the criteria. After several rounds of invitations and discussions, 16 participants were willing to join this study and share their stories. According to Moustakas (1994), an effective qualitative study should recruit 15-20 participants, while others (Guest et al., 2006) indicated 12 participants should be enough to reach data saturation. Therefore, in this case, 16 participants should be appropriate for the achievement of data saturation. As this study has a narrow focus on people of Jeju who are studying in one of the mainland universities in the South Korean peninsula, the participants needed to meet the following criteria:

-

The participant was born and raised in Jeju

-

Consider himself/herself as people of Jeju

-

Have lived in Jeju from early childhood to secondary school graduation

-

Currently been living and studying in one of the mainland South Korean universities for at least two years

-

Willing to share their stories with the researchers

-

At least 18 years old

-

Non-vulnerable person

Data collection

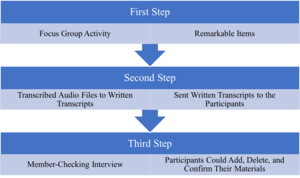

Three qualitative tools were used: focus group activities (Morgan, 1998), remarkable item sharing, and member-checking interviews (Merriam, 2009). First, based on the focus group activities, the researchers wanted to group different participants together to share their stories and understanding in a group format. During the focus group activities, the participants might share their stories, experiences, and understanding of their social identity. As there were 16 participants, eight participants were arranged in one focus group activity.

Before, during, and after the focus group activities (Morgan, 1998), the participants might email and show the remarkable items to the researchers and/or group members. The remarkable items could be visual items and pictures of their memories and important moments. The participants did not need to offer physical items to the researchers.

After the researchers collected the qualitative data from the participants, the researchers gathered and categorized the voice messages and images into written transcripts. The researchers sent the transcripts to each participant for the individual and private member-checking interview sessions (Merriam, 2009). During the member-checking interview sessions, the participants could confirm their qualitative data. More importantly, the participants might use this chance to add and delete their ideas from the previous sessions. Figure 1 outlines the steps for data collection.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing recommendations were announced. Although the government had reduced the limitations, it was important to avoid potential meetings with more than four people. Therefore, the data collection procedures were conducted online with a digital recorder. The audio messages were recorded. All participants agreed with this arrangement.

Data analysis

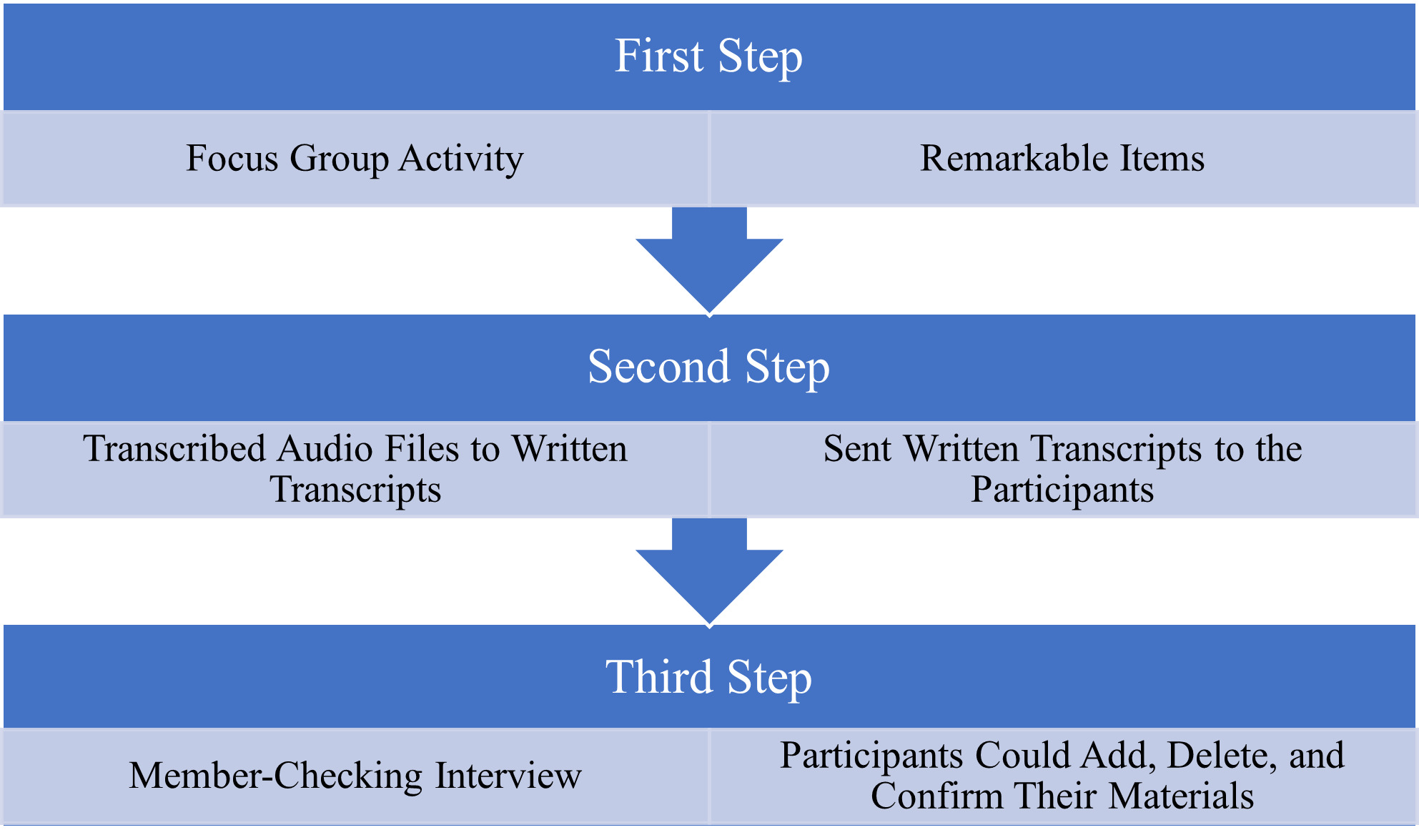

After the participants had confirmed their qualitative data, the researchers re-read the data multiple times to categorize connections and groups. The general inductive approach (Thomas, 2006) and the grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) were used to categorize and narrow the massive qualitative data.

First, based on the open-coding technique, the researchers used the technique to narrow the written transcripts into groups and themes, giving 20 themes and 21 subthemes (e.g., Korean citizens with a unique background, the Korean language connected Korean people together, Korean people should have different cultural backgrounds, etc.).

Second, the massive number of themes and subthemes should be further studied for an effective report. Therefore, based on the abovementioned themes and subthemes, the researchers further employed the axial-coding technique for secondary analysis. As a result, three themes and five subthemes were yielded based on the theoretical frameworks and research questions. Figure 2 outlines the steps for data analysis.

Human subject protection

Privacy is the most important factor, particularly in studies with personal backgrounds and experience. Therefore, the researchers kept all the signed agreements, personal contacts, audio files, written transcripts, remarkable item sharing, computers, and relevant materials in a password-protected cabinet. Only the researchers could read the materials. After the researchers completed the study, the materials were deleted and destroyed in order to protect the privacy of all parties.

Findings and discussion

Although the participants were not from the same family or family clans, all were born and raised in Jeju and shared many similarities, beliefs, and understanding as people of Jeju. During the focus group activities, the participants shared stories and experiences as groupmates expressing their experiences, challenges, and sense-making processes both as people of Jeju and Korean citizens. It is not uncommon for qualitative studies to use comprehensive sections for comparison. Therefore, the researchers combined the findings and discussion sections for a comprehensive understanding. Table 2 outlines the themes and subthemes.

I am a South Korean citizen, but I am not a mainland Korean

I am always a South Korean citizen…I do not have any challenges of this idea…but I do not think I am a part of mainland Korea…people of Jeju have their own ideas…about social identity…we are Korean…but it does not mean we are mainland Korean…while…mainland Korean people do not think people of Jeju are mainland Korean too…but we are Korean (Participant #3)

…being a South Korean person is my social identity…however, within the South Korean community…I was asked to identify my identity…or I would identify myself as a person from Jeju who is living in mainland Korea…because many provinces and cities are located in South Korea…South Korean people usually express their place of origin and city…in order to identify their roots…in my case, I am a person from Jeju (Participant #14)

All participants felt themselves to be South Korean citizens without question. However, they indicated that South Korean people categorize people’s backgrounds based on their place of origin. As indicated in Howe’s recent (2020) study, many parts of South Korea, particularly those close to Seoul, have experienced economic development and educational reforms. Jeju, however, as an isolated island, has not received economic development or financial contribution from the central government. In addition, Song (2018) expressed that due to the unique background and culture in Jeju, many mainland South Korean residents and people do not fully understand the unique cultures, backgrounds, and practices in Jeju. Some social stigma and bias could be created, such as discrimination,"sometimes, people called me Jeju person…but not a South Korean resident…because of my cultural background and language…but I surely confirmed my social identity" (Participant #15). Many people of Jeju argue that they are South Korean citizens but not mainland Korean, based on their place of origin:

I am a South Korean citizen…but I do not see…I am a mainland Korean…although I am studying in mainland Korea…my educational experience…would not change my understanding…as a South Korean citizen or…mainland experiences cannot impact my understanding and my identity (Participant #1)

Both South Korean and people of Jeju…can exist at the same time…but if some people need me to select…my place of origin would be more important…as this is my social identity…but again…I am sure that I am a South Korean…with Jeju background (Participant #12)

Self-identity: people of Jeju

As a nationwide belief, nationalism plays a significant role in South Korean people’s minds and social behaviors (A. E. Kim & Park, 2003). Personal background and place of origin impact Korean people’s self-identity, self-efficacy, and sense-making processes (S.-S. Kim et al., 2012), as indicated:

I was born and raised in Jeju…and I also believe…I am a South Korean citizen…but I further…indicated that I am a person of Jeju…a proud resident from Jeju Island…I have lived in the mainland for more than three years already…but I still cannot forget my hometown…Jeju…is my land…and this is my self-identity (Participant #2)

Based on the information from the participants regarding questions on self-identity, the researchers noted more than 50 times the participants self-identified as a person of Jeju. All participants strongly argued that they are South Korean citizens, but the keyword person of Jeju was mentioned as the strongest self-identity of all participants. For example:

I cannot forget my homeland because Jeju offers me food, land, education, friendship, childhood, parents, and families…I am not what I am without Jeju Island…my education, school, and time in the mainland…cannot change my self-identity as a person of Jeju (Participant #14)

This is how South Korean people identify themselves…we need to categorize our nationality…if we all have the same nationality…we will further categorize our city and place of origin…for example, someone from Jeju, and someone from Busan…in my case…I am happy with my identity…a student from Jeju (Participant #6)

In conclusion, in line with social identity theory (Tajfel, 1969; Tajfel & Turner, 1986, 1979), all participants indicated that they are all, without a doubt, South Korean citizens. Previous studies (M. H. Hwang et al., 2019; S.-S. Kim et al., 2012; Oh & Sung, 2017; Robinson, 1994; Walcutt et al., 2012) have highlighted that discrimination and social stigma based on unavoidable factors, such as place of origin and language, are not uncommon in South Korea. Based on the traditional thinking of social class and categorization, the participants indicated that they had established their own social identity as people of Jeju without the category of South Korean citizens (i.e., a small group within a large community or group). Also, collectivism (Han, 2017; Im, 2019) plays a significant role in South Korea. South Korean people tend to group together based on common similarities and backgrounds, in this case, place of origin. However, identifying themselves as a small group does not change their social identity as South Korean citizens as their nationality, although many argued that being people of Jeju better identified their background and social identity (Li et al., 2021).

My spoken language and living style

Some studies (Lynch, 2018; Wilkinson, 2009) indicated that language and culture could be significant elements that can divide a region. Previous studies (Yang, O’Grady, et al., 2019; Yang, Yang, et al., 2019) have highlighted the differences in the language and living style in Jeju from mainland Korea. Although many of the participants saw their nationality as South Korean citizens, the ideas of categorization and social identity strongly impacted their understanding and role within the region. The researchers captured two interesting ideas concerning differences between the mainland Korean language and the Jeju Korean dialect:

Vocabulary, grammatical structure, tone, and expression are not the same…as the Seoul (i.e. capital) Korean language…we have our own language…in the capital city, people call tree as namu (나무)…and in Jeju, we call tree as nang (낭)…also, in the capital…people call the restroom as (화장실)…and we call it the (통시)…we [people of Jeju] understand the capital language…but other Korean people cannot understand ours (Participant #9)

Although not all young people can speak the Jeju Korean language fluently…we can still understand the Jeju Korean language…many of our parents, grandparents, and community members…continue to use vocabulary and keywords…in the Jeju Korean language…many people of Jeju do not want to lose this unique language background and application (Participant #12)

Religious practice

In addition to differences in language and vocabulary, religious practice plays a significant role in the behavior and understanding of the people of Jeju. Traditionally, mainland Korean people follow Buddhism as their main religion. Although Christianity entered the Korean peninsula in the mid-20th century due to the effects of Japanese and American cultural diversity, Buddhism is still considered the major religious practice in South Korea. However, because of the isolation of the island of Jeju, Korean local folk religion plays a significant role in the religious practice of the people of Jeju (Yoo, 2018):

Unlike our mainland Korean counterparts…we have our own religious practice…many of us…follow Christianity because of the social media, TV, and media impacts…but we cannot forget that…people of Jeju have our own [local folk religion]…it is only available in Jeju…not other regions and places…perhaps other small towns still have [local folk religion]…but it must not be the same as ours [Jeju local folk religion] (Participant #16)

Although I do not believe in the…local religion in Jeju…but this is our unique culture…and we [people of Jeju] love this practice and proud of this practice…this is very special to us…because other Korean people cannot find our religious practice in the mainland…this practice and the dances…make me proud of my social identity (Participant #3)

The Korean Joseon dynasty (1392-1897), the Japanese colonial government (1910-1945), and the Park Chung-hee government from the Republic of Korea (1962-1979) strongly disagreed and disapproved of the cultural development, religious practices, behaviors, and activities of local folk religion. Although the governmental officials terminated and prevented the activities, Jeju local folk religion continued due to the insistence of the people of Jeju (Yoo, 2018):

The ancient dynasty, the Japanese government, and the current government did not like our Jeju religion…I do not believe in [local folk religion]…but I believe it is important to have this religion…because this is the original product of Jeju…we have our uniqueness, and we are proud of our own religious practices and activities…different cities have different representatives…in Jeju…we have our own religion (Participant #8)

The Korean local folk religion plays a significant role in the social identity of many people of Jeju (Yoo, 2018). However, as part of its centralization, the Korean government has tried to reform Jeju’s sociocultural perspectives, items, activities, and behaviors to show government power, authority, and management in Jeju.

We are proud of our identity…as people of Jeju…the central government in Seoul or the capital city…cannot change our uniqueness…because we are islanders…we have our language, religion, food, living style, education, and people…although the government’s policy…is very challenging…because they want to take over the control…and cancel some of our sociocultural behaviors…we need to overcome it…and people of Jeju in the mainland…many of us know…we need to continue our Jeju culture (Participant #6)

It is worth noting that local folk religion is one of the key points for many of the people of Jeju. Although Christianity impacted and influenced a large group of South Korean citizens, the participants believed that their local folk religion could represent their social identity as the people of Jeju. The participants are not practitioners of the local folk religion. However, the religion’s impact and existence play a role in their understanding.

We are proud of our uniqueness as people of Jeju

Jeju is a very special location…no people can find this unique, original, and cultural location in South Korea…in the mainland…people can see modern buildings, theme parks, shopping centers, and large cities…but in Jeju…we are unique…and we have beaches, forests, woods, and wild animals…we are called country boys…but we are proud of our culture in Jeju (Participant #5)

I enjoy my country background…and my unique language…and my religious practice and dance…people like pop music from Seoul…but I pretty enjoy the local country music…particularly the traditional music from Jeju…we need to keep this music active…otherwise, no one can play the traditional music anymore (Participant #10)

In conclusion, in line with self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1997), all participants indicated that they are proud of their unique culture and practices as South Koreans and people of Jeju. Although many accepted that their place of origin and hometown are not well-developed, they are proud of the rural and suburban environments of their hometown. More importantly, the language, religious practice, culture, and environments are some of the significant elements and keys for their self-efficacy and social identity (Li et al., 2021; O’Grady et al., 2022; Song, 2018), said, "yes…we are not rich…and we are from the countryside…but this is our hometown and our land…we are fine with our place of origin…as South Korean and people of Jeju" (Participant #7). As seen, the uniqueness and social identity served as the key points for the participants’ self-efficacy, which can help them to overcome challenges and problems due to their unique Jeju dialects and sociocultural practices.

Aligning with social identity theory (Tajfel, 1969; Tajfel & Turner, 1986, 1979), the sociocultural perspective, understanding, behaviors, religious practice, and language can be different in many islands and isolated and remote regions. Although some islands, such as the Faroe Islands (a self-governing nation under the external sovereignty of the Kingdom of Denmark) and Greenland (a constituent country under the Kingdom of Demark) may continue to be impacted by their home country, it is not uncommon to see differences between remote islands and their home country (Marutani et al., 2020). In this case, the participants indicated that their language, living style, and religious practice played significant roles in their social identity in identifying themselves as people of Jeju, said, "the unique culture in Jeju makes me proud of my social identity" (Participant #8). Although many felt that they respected the sociocultural perspectives and behaviors of their mainland counterparts, they were proud of their traditions and customs unique to their homeland (Wang & Zhong, 2022). Although previous Korean governments and dynasties did not recognize the uniqueness of Jeju, many of the islanders continue to celebrate the island’s unique traditions to pass them on to the next generation.

Social stigma and discrimination

Social stigma and discrimination…are very common in all parts of the Korean culture…we categorized people based on their age, gender, place of origin, background, education, family structure, family clan, and religious practice…all elements can be used to discriminated and categorized people in Korea (Participant #10)

In my Korean language…I have a Jeju accent…and sometimes, I use the Jeju vocabulary…I don’t speak the Jeju dialect fluently…but I understand some vocabulary…because we [people of Jeju] usually use the vocabulary…for normal conversation (Participant #4)

Place of origin, language, accents, and educational background are common elements in categorizing people in South Korea (An et al., 2022; S.-S. Kim et al., 2012; Seol & Skrentny, 2009; Song, 2018). Although Korean people consider collectivism and Confucianism connecting all South Korean people as South Korean citizens, social identity strongly impacts the sense-making processes of the people of Jeju in relation to their mainland counterparts (Han, 2017; Im, 2019; A. E. Kim & Park, 2003; Wu et al., 2021; Xiao & Hu, 2019). Regarding the place of origin, two interesting stories were captured:

People in the mainland…when we introduce ourselves to our mainland counterparts…we need to disclose our name, age, and place of origin to each other…when I told my counterparts and friends about my place of origin…from Jeju…many showed a negative opinion…and call me a person from the countryside privately…but I understood they called me a country person (Participant #4)

It is not uncommon that the mainlanders call us the people from rural islands…or barbarians from Jeju…this is the stereotype about Jeju and other islands in South Korea…when they knew I am from Jeju…many asked me…can I do farming…can I milk the cows…how many green tea farms in Jeju…these questions are very negative and aggressive…impolite (Participant #5)

The stereotypes and negative images of the people of Jeju

Many of my mainland classmates asked me if I had a farm in Jeju…are we still living in the lodge…do we have television and internet…these are negative questions…people from the mainland should understand our living standard in Jeju…but I guess they want to make fun of us…and promote their background (Participant #13)

It is not uncommon for people of Jeju to be made fun of due to their background, place of origin, and stereotypical media images. Almost all participants, when asked about their family background and farming technologies because of their place of origin, felt:

The mainland people always believe Jeju is a land of cows, pigs, and chickens…some of them believe we all have farms with teas and vegetables…but many of us [people of Jeju] live in the building and work in the business industry…but many called us country boys and rural farmers…it makes me sick (Participant #11)

It is also not uncommon that people from rural communities, including the people of Jeju, are asked to go back to their rural communities and islands by people from the capital city. There is a belief in many people from the metropolitan regions that people of Jeju and other rural communities come to the metropolitan to steal their career opportunities:

My intern supervisors…and my classmates from the capital city…asked me to go back to Jeju…because there are no career openings for people from the countryside…we are all South Korean citizens…and I have my right to work in South Korea…because I do not need any visa…but my counterparts, classmates, friends, and even supervisors…look down me because of my place of origin…I am very mad and sad because of the reactions from other mainland counterparts (Participant #15)

I will go back to Jeju to serve my community

I will go back to Jeju for my family…although not all industries are available… my soul and my goal are in Jeju…we need to go back one day…we are Korean…but we do not belong to the mainland…we need to go back and sleep on the land…where offers us the food and water…people need to go back to their homeland and offer the services (Participant #7)

Many island studies (Bettencourt, 2010; Dos Santos, 2022; Kuroda et al., 2021; Song, 2018; Tiku & Shimizu, 2020) have shown that workers and human resources usually want to stay on the mainland, in internship sites and places with work opportunities. However, the participants in this study indicated that returning to their home in Jeju was their priority as many had experienced issues of social identity and social stigma due to their being from Jeju (Yang, Yang, et al., 2019). For example:

Perhaps people in other parts of the mainland…such as rural communities in the mainland, will go to the capital city or metropolitan for better opportunities…but for many students and people in Jeju…going back to Jeju is the final goal…as our destination…Jeju is our land…and this is the place where we should stay and sleep after retirement…I can stay in the mainland for education and internship…perhaps several years of experience…but we [people of Jeju] still want to go back to Jeju…I need to offer my services and knowledge to my homeland (Participant #1)

In conclusion, in line with social identity theory (Tajfel, 1969; Tajfel & Turner, 1986, 1979) and self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1997), the stereotypical image of Jeju and island life played a significant role in the experiences and challenges of many people of Jeju. Although some argued that they have a strong social identity as South Korean citizens, many experienced challenges when entering mainland communities. It appears that mainland Koreans do not want to accept the Jeju islanders as South Korean citizens and people (Li et al., 2021). Many of the participants had experienced negative opinions and reactions, such as being asked to go back to Jeju due to their accents and behaviors. These negative experiences challenged their feelings and self-efficacy.

However, many actively cherished the negative experiences and challenges, seeing them as the reason for returning to their homeland of Jeju for their long-term development. It is worth noting that the self-efficacy of this group of participants was very high, and they channeled their negative experiences into energy for professional development. For example: “I love the challenges and discrimination from my supervisors…I am sure that I am a person of Jeju…and I do not feel bad because of my place of origin” (Participant #3).

Limitations and future research development

First, there are nearly 3,500 islands located in the South Korean territory. However, only Jeju was selected for investigation. Although the results from a group of people of Jeju may reflect the situations of other islanders, the responses and experiences may be different. Therefore, future research directions could investigate the issues and experiences of other South Korean islanders to capture a holistic picture of the current situation in South Korea.

Second, university students were selected as participants. Although the voices of young people may reflect the situations of other islanders, adults, middle-aged people, professional workers, and young children, others may have different voices and experiences in terms of career development, family responsibilities, and financial considerations. Future research studies could investigate populations other than university students, particularly people with working experiences in mainland regions.

Third, as mentioned above, only Jeju islanders were selected. However, it is not uncommon for people from other rural communities to move to metropolitan regions and cities for their personal development. Although the challenges of groups from the rural mainland may not be the same as those of islanders, the issues of these groups of people should be studied. Therefore, future research studies could investigate people who decide to move to metropolitan areas for development, particularly people from rural communities.

Fourth, the current study tended to focus on the social identity and challenges of the people of Jeju. The historical and sociocultural discussions between mainland Korea and Jeju Island are missed. Researchers in history, humanities, and anthropology may use this study as one of their references to discover the knowledge in South Korea, particularly in the areas of language, cultural practice, and religion.

Contributions to practice

First, social identity is an interesting research topic for many researchers of island studies. Although some studies have been conducted in these areas, such studies have usually focused on the issues of islanders in other countries and regions. The results of this study will be one of the first studies in this area for the people of Jeju. The outcome of this study will fill the research and practice gaps for the people of Jeju and the surrounding regions.

Second, Jeju has experienced a significant challenge of human resources and workforce shortages due to its isolation and island nature. Despite this, the government has not established long-term or effective plans to understand and investigate the shortages, particularly the retention of the skilled and educated people of Jeju. Therefore, the outcome of this study will fill the research and practice gaps in understanding how the government can keep professional workers in Jeju.

Third, it is known that sociocultural perspectives and practices in Jeju differ from mainland regions. However, no contemporary studies have focused on how these sociocultural perspectives and practices can impact the behaviors, career decisions, social identity, and experiences of the people of Jeju, particularly those who undertake educational qualifications on the mainland. Therefore, the outcomes of this study will fill the research and practical gaps in this area.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Jeju is the largest isolated island in South Korea, located between the Korean peninsula and Japan. Due to its location and isolation, Jeju continues to have its own sociocultural perspective, understanding, behaviors, language, and religious practices. First, based on the findings of this study, the participants indicated that due to the islandness of Jeju, they had developed their self-identity as people of Jeju and South Korean citizens, but not mainland Korean from the Korean peninsula. More importantly, although not all participants can speak fluent Jeju dialect and follow the traditional local religion in Jeju, the unique sociocultural development and customs play significant roles in their self-identity, self-efficacy, and sense-making processes as people of Jeju.

Second, many participants experienced social stigma and discrimination in the mainland Korean peninsula due to the sociocultural development and customs in Jeju. However, the participants indicated and believed that the social stigma, discrimination, and misunderstanding of their counterparts enhanced their self-identity, self-efficacy, and understanding as people of Jeju. The participants further believed that due to these challenges, they would like to go back to their place of origin for further development and services. In short, university students and graduates are important assets in many countries and regions. Understanding self-identity, self-efficacy, and challenges is important, particularly for students from the island provinces and regions. This study offers a holistic picture and understanding of a group of people of Jeju.