Introduction

Pacific island states are experiencing the effects of climate change which have had a wide-ranging and increasing impact, especially in smaller states where the ability to manage and respond to these consequences is usually more difficult and livelihoods are more dependent on the environment (Connell, 2013; Latai-Niusulu et al., 2020). The small Pacific island state of Samoa has experienced significant environmental changes in this century, particularly cyclones and floods, not all of which are attributable to climate change, notably a devastating tsunami in 2009. These events affected the lives and livelihoods of most people, especially in coastal areas, where the bulk of the population is concentrated. This paper seeks to examine how children, especially younger children, have experienced, perceived, accounted for, and responded to these changes. It focuses on the extent to which relatively young children recognize and respond to climate change.

Most studies of the perception of and response to climate change have not surprisingly focused on adults, because of its impacts on their livelihoods, their perceived ability and necessity to respond, and the relationship between policy, practice, and culture. By contrast, the role that children and youth can play in making communities more resilient has largely been ignored, despite children being one of the more disadvantaged groups, mentally and physically, in disasters and climate change (Lawler & Patel, 2012). Many studies explore the role of climate change education (Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, 2020). Relatively few studies with limited exceptions (e.g., Chaimontree, 2010; Gautam & Oswald, 2008), and even fewer in small island states, focused on children’s perceptions of climate change, despite the potential significance of children’s knowledge and their present and future role in shaping resilience and despite the fact that disproportionate impacts on children have been well documented (Foley, 2022). Moreover, most of the studies on the relationships between children and climate change focus on adolescents and older youth, rather than younger children, and often therefore on activism or the potential for activism and have been undertaken in high-income countries (Lawler & Patel, 2012; Lee et al., 2020; Scott-Parker & Kumar, 2018).

The present study intentionally included children younger than in any other comparable study. Some general studies have mentioned the impacts of climate change on children, including children in the Pacific Islands, ranging from health issues to the destruction of homes and livelihoods, alongside the recognition that children are often particularly at risk from the impacts of climate change that are most critical in the island states in the global south (Bartlett, 2008; Britton & Howden-Chapman, 2011; Burton et al., 2011; Lawler & Patel, 2012; Lindsay et al., 2011; Urbano & Maclellan, 2010). This mainstream exclusion of children may be linked to widespread Pacific assumptions that children are – or are expected to be – silent, passive, and dependent. These views are particularly true in Samoa (Lee Hang, 2011; Tanielu, 2004), where children are seen as people whose views and opinions do not matter, and who only acquire knowledge and wisdom later in life. However, children will grow to be potentially active citizens and future leaders.

To bridge this considerable gap in the literature, this paper examines the knowledge and awareness of climate change amongst children in the small Pacific island state of Samoa, through using multiple tools including focus group discussions and picture drawing. Studies engaging children have shown they are knowledgeable, active, and capable of commenting on their everyday lives and looking critically at local problems (Christensen, 2000; Ergler et al., 2020; Holloway & Valentine, 2000; James et al., 1998; Stratford & Low, 2015). Moreover, there are early indications that children who have been exposed to challenging environmental disturbances were able to think about their futures and display feelings of hope, healing, and recovery. This study builds on these indications (Latai & McDonald, 2016). This study, perhaps the first to be undertaken in the Pacific islands, centres on the dominant island of Upolu and focuses on both urban and rural Samoan villages on different coasts and inland to examine the extent to which Samoan children are aware of the multiple dimensions of climate change affecting Samoa, including rising temperatures, cyclones with heavier rainfall and stronger winds, and how these may be impacting, to varying degrees, different parts of this island group, and different genders and age groups. The children’s discussion of climate change impacts covered various themes, related to observation, reception, and comprehension, and recorded some benefits and many challenges from climate change. It thus examines the extent to which, on a small tropical island, children are able to distinguish local variations in climate change and its impact.

The Place(s) of Children

Current discussions of climate change in Samoa have previously been dominated by the views of government officers, consultancy firms, and civil society workers. However local people’s knowledge and perspectives, including those of children, are important in understanding localized climatic and other environmental changes and human adaptability, now and into the future (UNICEF & PLAN, 2010). Studies focusing on children in the Western world have shown that children are social actors in their own right. They are knowledgeable, rather than uninformed or becoming-adults (Christensen, 2000; Ergler et al., 2020; Holloway & Valentine, 2000; James et al., 1998; Mycock, 2018; Procter & Hackett, 2017). Moreover, children’s awareness and knowledge contribute to understanding environmental changes in particular places and related human adaptability. In parts of Asia (Berse, 2016, 2017; Chaimontree, 2010; Gautam & Oswald, 2008; Jabry, 2003) and South America (Tanner, 2010) children, especially those above 10 years old, are active observers of environmental risks and changes, having seen changes in temperatures, seasons, and rainfall, in addition to having the ability to discuss how these events affected their lives. Children were keen and able to discuss climate change, stimulated by what they learnt in schools and media portrayals of the causes of recent disasters. Several studies have also shown that children were able to explain the adaptive measures they were taking to cope with climate change, including recycling, reducing the use of plastics, and re-planting trees (Berse, 2017; Lawler & Patel, 2012; Ojala, 2012, 2013, 2016; Searle & Gow, 2010). However, in mainstream approaches and theoretical debates on climate change and disaster risk reduction, there remains a major gap in understanding how children in different contexts perceive climate change, understand the risks it poses, and what they do with this information (Berse, 2017; Tanner, 2010; UNICEF & PLAN, 2010).

With few exceptions, there is little information on how children perceive future climate change, and no studies have been undertaken in the Pacific. Existing studies on Samoan children affected by the 2009 tsunami revealed that children, who were exposed to this traumatic event, think about their futures and display feelings of hope, healing, and recovery. Here, as elsewhere, the experience of disasters has prompted children (and others) to think more about the environment and contemplate wider environmental issues. Children thought more about the environment than prior to the tsunami, and were more interested in climate change issues, and in mitigation (Latai & McDonald, 2016; cf. McDonald-Harker et al., 2022). These ideas contribute to the theoretical framing of this study, which contests traditional Pacific assumptions that children are passive and dependent.

Until recently the voices of islanders themselves were largely absent from earlier studies of climate change in the Pacific, which had initially largely been scientific (e.g., Becker et al., 2012; Meyssignac et al., 2012). That has however changed and the perceptions and responses of islanders are of considerable significance (e.g., McCubbin et al., 2015; Rudiak-Gould, 2011, 2013; Savo et al., 2016) and include those of adult Samoans (Barbara et al., 2023; Beyerl et al., 2019). Small islands, including Samoa, are widely considered to be the loci of consequential future environmental changes in the Pacific region. Islands and island states are dynamic entities that have the capacity to adapt to and endure change. While it is widely accepted that small islands and small island states are often at particular risk to environmental changes (Connell, 2013; Pelling & Uitto, 2001), it is equally and increasingly apparent that positive responses and mitigation are feasible as is true in quite different island environmental contexts and times (Foley, 2022). Both ecological and human systems that experience disturbances have a capacity to adapt, respond to and survive environmental (and other) changes (e.g., Folke et al., 2003).

Island communities facing unpredictable environmental challenges, including climate related changes, do not necessarily mean that islanders or island societies lack agency and are wholly vulnerable (e.g., Lauer et al., 2013; Schwarz et al., 2011). Rather, growing awareness of the causes, significance, and past exposure to disturbances, some of which are part of climate change, can enable societies to be more aware and more capable of dealing with possible impacts of future climate change, as is certainly true of Samoa (Barbara et al., 2023; Latai-Niusulu, 2017; Latai-Niusulu et al., 2020). In Samoa, as elsewhere, development of such local responses has occurred (e.g., Flores-Palacios, 2019; Narayan et al., 2020), with outcomes that can entail a greater hybridity and integration of modern and indigenous knowledge (McMillen et al., 2014; Roche et al., 2020; Vickers, 2018). The theme of positive response has been reiterated in psychological studies of resilient people who thrive under adversity (Kidd & Shahar, 2008; Mahoney & Bergman, 2002; Waller, 2001). Awareness and sensitivity to climatic changes has been identified as an indicator of human resilience, where this enables and entails the ability to develop specific coping mechanisms.

To develop an in-depth understanding of the adaptability and resilience of islanders, the importance of engaging with residents of places is paramount. This notion is echoed by many other scholars in the Pacific region (Fletcher et al., 2013; Lauer, 2023; McMillen et al., 2014) who stressed the importance of indigenous perceptions of island adaptability and resilience. Resilience emerges from local awareness and understanding through the involvement of local people, including children, who may otherwise be excluded from discussions of development.

The objectives of this study were to explore the awareness and sensitivity of Samoan children to climate change and other environmental challenges, assess their adaptability, and to assess whether children’s perceptions could reveal localized climatic conditions and changes in the environments where they live. Thus, we seek to differentiate at a small scale, and for the first time, how children in different villages and of different ages respond to environmental change. The two research questions center on, firstly, what do Samoan children understand about current and future climate and other environmental changes, and, secondly, how have they developed this knowledge?

Samoa

The study, undertaken in 2020-2021, focused on children between the ages of 6-15 living in coastal and inland villages on both the north and southern parts of the island of Upolu. Samoa is an independent Polynesian state with a population of about 200,000, comprised of two main high islands, Upolu and Savaii, and two much smaller inhabited islands (Figure 1). Three quarters of the population live on Upolu, many in or near the capital city Apia (Samoa Bureau of Statistics, 2016). Most people live in villages located along the narrow coastal plains of the main islands, a typical Pacific context of ‘coastal squeeze.’ Most of the country’s important physical and social infrastructure is on the coast, while as much as 80% of the 400 kms coastline is regarded as sensitive or highly sensitive to erosion, flooding, or landslides (Daly et al., 2010; Kumar & Taylor, 2015). Samoa has a basically agricultural economy with most households outside Apia living a semi-subsistence lifestyle, based on root crops, supported by animal husbandry and fishing. Remittances, especially from American Samoa and New Zealand, are extremely important, and increase following hazard events. Cyclones are regular occurrences and flood events have been frequent. Apia is particularly prone to flood impacts, partly because of the configuration of its seawalls. While separate predictions do not exist, the predicted increase in surface air temperatures in the central Pacific region range from between 1°C and 4°C, and associated sea surface temperatures will likely be 1°C to 3°C greater by 2070. Sea level has risen by 4mm since the early 1990s and is expected to rise between 0.19 and 0.58 meters by 2100. These changes will be marked by a greater incidence of hot days and nights, and extreme rainfall events (ABM and CSIRO, 2011, 2014). Recent evidence suggest that these changes are already occurring, with more cyclones, storms and flood events, and people responding by changing fishing and agricultural strategies and relocating inland (Cassinat et al., 2022; Flores-Palacios, 2019; Laalaai-Tausa, 2022).

Methodology

Constructivist ontology and interpretivist epistemology principles were used to frame the study since it aimed at interpreting and developing an understanding of human experiences. Both perspectives support a subjective view of the world and the existence of multiple truths. The interpretive paradigm recognizes the process of discovery and emphasizes understanding (Sarantakos, 2005). In this case, the combination of comments and stories told by the children during focus group discussions and their drawings, enabled the understanding of a reality based on culturally defined interpretations and personal experiences.

To ensure that the research findings were representative of varied experiences from across the island, we involved children living in different types of villages such as those located along the coastal and inland parts of Upolu as well as villages located in the urban and rural areas. The surveyed villages were the somewhat inland Moata’a, Vaimoso and Moamoa on the northern coast of Upolu, and Salani, Utulaelae and Sapo’e on the southern coast (Figure 1). The three southern villages had been affected by the 2009 tsunami that killed 149 people (including many children) on the south and east coasts. More than 40% of people in each village were under the age of 14.

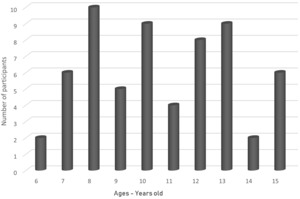

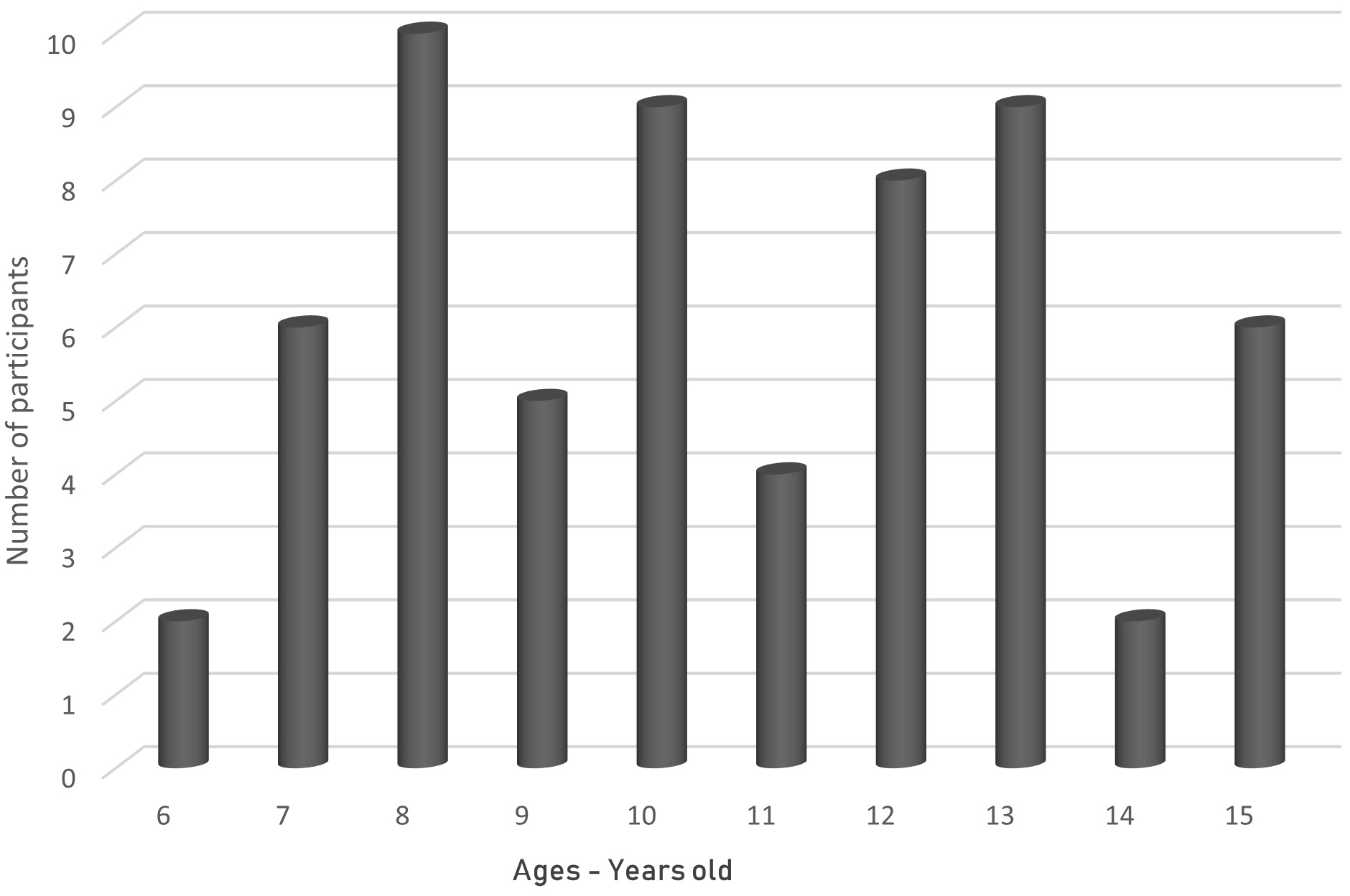

Focus group discussions and drawing pictures were the main methods of gathering information. One to two semi-structured focus groups of four to five children were held in two stages in six villages. The study included 60 children between 6-15 years old. Half of the children lived in urban villages and the other half lived in the rural parts of Upolu island. The minimum age for participation was 6 years old since the researchers believed that these children were already in their second year of formal schooling and would be able to respond to the questions posed. 60% of the participants were females. There were fewer 6- and 14-year-olds with the majority of participants being 8-, 10-, and 13-year-olds (Figure 2). Age and place of residence were used to break down the sample, as evident in the latter sections of this article, because these variables influenced the children’s responses. Pseudonyms of the children’s names are used in this article to maintain the confidentiality of the participants.

Cultural protocols were incorporated into the study’s design and were important for ensuring the validity of the research findings. The project aims and objectives were discussed, in Samoan, prior to the actual research with the children and their parents. Written copies of invitations, information sheets and consent forms for both parents and children were prepared in Samoan and signed before the focus groups were implemented. These documents were part of our ethical clearance approved by the National University of Samoa. As Samoans, the key researchers were well aware of cultural expectations surrounding the gathering of information, such as proper clothing, language, appropriate behavior, and traditional gifts. These were followed in order to gain the trust of the parents and the children. To ease any feelings of discomfort, the focus groups were held in the villages of the children and in spaces they were familiar. All focus groups were held in the Samoan language and facilitated by the researchers and local villagers known to the children. All were held in open Samoan houses that were not only cooler but allowed the children to freely move inside and outside of the venues. The facilitators and researchers introduced the themes and facilitated the focus group discussions. We were aware that having an older person facilitating could create tensions and might intimidate the children so we took care to speak softly and respectfully to the children and did our best to treat all of them the same. We found that the presence of older people helped to ensure each child had a turn to speak and express themselves freely and openly.

Children were initially asked to talk about the weather, Samoa’s climate, current and future changes in the climate, and related impacts. The children were then asked to draw pictures of current and future changes in Samoa’s weather and climate and/or impacts. Each child then took turns explaining their drawing to the researchers. During the child’s explanations, the researcher would ask, in Samoan, the questions “Why do you know that?” and/or “How do you know that?” These questions gained information to answer the second research question of this study.

The combination of focus group discussions and drawings encouraged the participation of children, despite a perception that younger Samoans can be unquestioning and silent, particularly in the presence of elders (Tanielu, 2004). The cultural value of fa’aaloalo i e matutua [respecting your elders] is perhaps the most common and best known of the cultural factors that underpin this supposed silence (Lee Hang, 2011). Our observations during this study support other recent research (Freeman et al., 2023) which argued that participatory methods, such as drawings, enable children to speak and be heard, therefore allowing researchers to better understand children’s life worlds and their relationships with the places they live. Most of the children eagerly grabbed the coloring pens and paper when they were asked to draw. We noticed many children checking each other’s work and discussing their drawings but we did not capture what was said until each child was ready to come up and explain his or her drawing. Some children, especially the younger ones, took their time but they had all drawn something by the end of the session. Some children who were relatively silent during the first part of the focus group, spoke out when they were explaining their drawings. These one-on-one sessions also allowed the researcher to probe the child and extract more information compared to the general group discussions. Talking and listening to each other during the focus group discussions also encouraged participants to think more deeply and reflect on their own views and knowledge. As observed elsewhere for adults (e.g., Kitzinger, 1994), the children did not simply agree with each other. Sometimes they disagreed, questioned each another, and tried to convince others of the validity of their own viewpoint. This mostly happened when children 10 years and above were placed close to the younger children’s group (those below 10 years old) and they could hear what the younger children were saying. This behavior affected the younger children’s responses so the two groups were placed farther away from each other. Those below the age of 10 found it more difficult to discuss some of the questions. Their pictures were also relatively simple and without the detail of those of children between 10 and 15 years old.

Narrative-descriptive methods were used to organize and interpret the study findings. Various analytical tools were utilized to extract themes from the raw data and decide which were significant. Notes taken during focus groups and audio versions assisted in the production of data transcriptions, involving re-writing the field notes and listening to the audio versions to provide any missing details. This was done in Samoan and then translated into English. Revisiting the recordings, transcripts, and notes taken during the interviews, focus groups, and field observations was done to validate translations. The transcriptions in both languages were then assigned code numbers and filed according to the relevant village. Drawing sketch maps and sifting through the children’s drawings as well as photographs taken during the fieldwork were also organized and filed under the relevant village.

The first level of coding involved initial attempts to understand participants’ responses and organize these under the two research questions, using descriptive and analytic coding as outlined by Cope (2003). This involved examining each transcript for terms that the participants frequently mentioned and highlighting phrases they used. The main issues and themes were then transferred into a village summary table and organized according to their relevance to the main research questions: a process of ‘fracturing’ the transcriptions and ‘lumping’ similar data together (Tracy, 2013). A second round of coding was carried out to determine significant themes in the findings through content analysis. Counting the frequency of a word or phrase in a given data set to give an idea of the prevalence of thematic responses across participants (Namey et al., 2008; Ryan & Bernard, 2003).

The children were asked three key questions:

-

What changes associated with climate change or other environmental processes are currently taking place and are likely to occur in the future?

-

What are the impacts of current and future climate change?

-

How did you gain this knowledge and awareness?

The children’s responses to the questions posed in the focus group discussions are analyzed below in response to these key questions, and their responses are categorized and examined according to where they live, in order to demonstrate variations in their perceptions.

Children’s environmental perceptions: rising temperatures, heavier rainfall, and stronger winds

Age and place of residence influenced the study findings more than gender. There were fewer differences in the responses of boys and girls. The children’s level of understanding became more complex and subtle with age. Children as young as 6 years old were generally aware of the weather and climate of their village areas. The majority of those between 10 and 15 years old were both aware and able to articulate changing climatic patterns—in the present and into the future—and the impacts of such changes. Those between 10 and 15 years old were able to give relevant responses that were longer than the one-word responses of many of the younger children. Older children’s responses contained not just localized changes in the climate, such as rising temperatures and sea level rise, but also global changes, such as melting ice, associated with climate change. Moreover, their responses showed they understood the connections between slight changes in the climate and other aspects of the environment.

Where the children lived on Upolu also influenced their responses. Thus, children living close to rivers, such as those in the inland north parts of Upolu and those in coastal south parts, explained that heavier spells of rainfall had caused not just rivers to flood but the sea to become rough and polluted, making it difficult for transport and for fishermen to go out to sea. The children developed their awareness through observations of natural processes as they played and carried out household chores, and, additionally, by listening to family members, attending school, and watching various media reports on television.

Most children stated that the current climatic changes involved increasing temperatures, heavier rainfall, stronger winds, and cyclones. The majority of children, in all three parts of the island, both coasts and inland, stated that the most significant change was that the temperature was increasing. The way that they described the “heat” differed somewhat between villages, suggesting slightly different experiences and perceptions of “rising heat.” For instance, some of those living on the northern coast used the Samoan word “aasa” (“burn like hot stones”). One child living in the northern inland part of the island said “mamafa tele mugala” (“the heat is very heavy/intense”) causing his body to heat up. Children on the southern coast said "days are getting hotter." While most children recognized rising temperatures as the most significant dimension of current climate change, their combined experiences revealed that the perceived intensity of temperature tended to decline from the coast inland and to the south of Upolu. The phrase ‘the sun burns’ appropriately describes the experience of rising temperatures in the northern part of Upolu, the leeward and drier side of the island. The north coast is also characterized by coastal deforestation that intensifies the heat of the sun, coastal reclamation, and a greater density of houses and urban infrastructure. Some children noticed that the dry season was getting longer and that strong winds and heavier rainfall tended to occur suddenly.

The majority of children’s responses to the impacts of climate change focused on adverse impacts. Those living in northern Upolu referred to the impacts of rising temperatures, namely as bodies being hot, plants not growing well and the spread of diseases. Most responded that the heat caused ‘the body to heat up,’ people were more likely to become tired and fall asleep or become sick. The sun had also caused the grass and other plants to die or dry up. Some children noted that heavier rainfall and strong winds had also affected their piped water. Flood waters which entered catchment areas polluted piped water sources and caused stomach illnesses like diarrhea. Heavier rainfall had also caused the spread of viral diseases such as influenza.

Children living on the south coast provided more detail on the adverse impacts of frequent heavier rainfall and stronger winds, and also mentioned ‘increasing temperatures’ more frequently. Stronger winds and heavier rainfall were frequently described as ‘bad weather’ events. According to many children, the combination of these events, which occur suddenly, often caused flooding which sometimes destroyed peoples’ homes and food gardens and resulted in run-off polluting the sea. Sina, a resident of Salani, explained to the researchers that her drawing (see Figure 3) depicts the Salani River and the sea turning ‘dark brown’ when sudden spells of heavy rainfall occur. She said, “When it rains heavily, the river and the sea turn brown and we cannot swim. My parents would tell us not to go into the river because it is not safe.” Some children on the south coast also mentioned that heavier rainfall had polluted their water supplies and caused diseases.

Not all impacts were perceived as negative. Children made positive references to how climatic change could also benefit people. Lani, who lives at Moamoa, drew Figure 4 and noted on her drawing that a positive impact of rising temperatures is that it was useful for drying laundry (aoga e faamamago ai tagamea), especially their school uniforms, while rain could cool bodies, and enable them to enjoy play more. She also wrote that the rain was also useful to wet the soil (aoga e faasusu ai le laueleele), while Tema explained, according to his drawing (Figure 5), that the rain can replenish rivers and help plants grow.

Rain could be both positive and negative. Iona, a young Salani boy, said “Playing in the rain is fun… there are water holes and puddles that we play in when it rains but rain can also make us tired and sick… and also because it rains suddenly, I cannot carry out my chores.” More pertinently perhaps, “When it rains puddles become breeding grounds for mosquitoes.”

Future climate changes

Children also had views about future climate change and its possible impacts. Stronger winds and cyclones, frequent and heavier rainfall, and increasing temperatures were the most commonly mentioned future climatic changes. Children living close to rivers, such as those in the northern parts of the island (particularly in urban Apia) and those in coastal southern parts, explained that the consequence of heavier rainfall had caused not just rivers to flood but the sea to be rough and polluted, discouraging fishing. That also influenced their own lives. As one child said “The Salani River was flooding and murky and we couldn’t swim because the sea got dirty.” Some children also mentioned that sea level would rise. The children’s descriptions of future climate change showed that those living on the north coast of Upolu perceived rising temperatures to continue and be the most significant dimension of future climate change. However, those living inland and on the south coast imagined heavier rainfall as the most significant possible dimension of climate change that they would be likely to experience.

Sea level rise was only mentioned by children living on the south coast although this dimension of climate change was evident in the drawings of most children living in the north. Thunder, lightning, and tornadoes were also mentioned by children living in the south. The possible impacts that the children mentioned included the destruction of houses by flooding, stronger winds, and that coastal land and peoples’ homes located in coastal areas would be inundated by the sea. To some extent, therefore, their perceptions were influenced and mediated as much by their own experiences in the different parts of the island as by media or the schools.

Like their discussions of current climate impacts, the majority of children’s responses focused on possible negative impacts. However, their drawings, and explanations of their drawings, revealed some positive views of future climate change and the adaptability of Samoans. For instance, Ela, a 13-year-old girl living in Moata’a, a village on the north coast of Upolu, stated that her drawing portrays the possibility of plants withering and homes inundated by water due to rising temperatures and seas (Figure 6). She said, “the changes are the heat and the sea coming onto the peoples’ houses, the houses can be covered by water… I have drawn these houses further inland and higher up the hills so the people can be safe. I think coconuts will continue to grow, further inland and higher up, providing food and other important household items.” Ela also drew a faleoo – a climate friendly Samoan open house and an umu - a Samoan kitchen. Like most children, she explained that she lived in a closed European house and in an area dominated by closed European and square cemented Samoan houses (fales). Ela’s drawing suggests some degree of recognition of climatic changes and flexibility in response. In thinking about adapting to future climate change, she drew a faleoo suggesting the importance of open houses, being easier and cheaper to build and re-build when they are damaged by strong winds, as they are made from locally sourced materials, and also cooler compared to closed European houses.

The occurrence of a traumatic event influenced how local children think and talk about their environment and related changes. Some children mentioned such non-climate related events as tsunamis and earthquakes. Many of those who mentioned both of these lived on the south coast of Upolu, which was directly hit by the 2009 tsunami. These children, now aged 10-16, experienced the tsunami destroying coastal parts of their villages. They did not, however, talk about these events when they were asked to describe future climate change and its impacts. However, intriguingly, those living in the north of Upolu mentioned both as part of future climate change. Their responses suggested they feared the occurrence of this in the future because of climate change. Those living in the south of Upolu may have realized that tsunamis were not part of climate change, while many children in the south of Upolu now live inland where their houses have been rebuilt after the tsunami, and may no longer see this as a threat.

Discussion

This study confirms multiple observations in the literature that children are informed beings (Christensen, 2000; Holloway & Valentine, 2000; James et al., 1998) and that this is as true of Samoan children as elsewhere (Ergler et al., 2020; Freeman et al., 2023). Samoan children can ‘read a place’ (Mycock, 2018; Procter & Hackett, 2017) and observe changes currently occurring in a place. All the children were aware of the general climatic conditions of the places they lived in and how certain components were changing. Most existing studies (e.g., Berse, 2017; Gautam & Oswald, 2008; Tanner, 2010) which feature children’s perceptions of climate change focused on children above 10 years old. The present study showed that generally children as young as 6 years old were aware of the weather and climate where they lived. Most children, especially those 10 years old and above, recognized and were able to articulate that the climate was changing. This is similar to observations of children in Asia and other parts of the world (Berse, 2017; Gautam & Oswald, 2008; Lawler & Patel, 2012; Ramos et al., 2023; Tanner, 2010).

Most of the changes mentioned by the Samoan children matched the information issued by various regional and national organizations for Samoa and the Pacific region. Indeed, most of their responses were similar to those of adults in Samoa, especially on the south coast of Upolu (Flores-Palacios, 2019). However, children related changes through their own experience, recognizing changes through their own eyes, for example, in relation to play, as much as it is being derived from the media or the classroom. They related changes to their own experiences and to mediated household activities, most evident in the slight, but significant gender variations. Most girls mentioned that the heat was useful for drying laundry. Boys tended to talk about the impact of climate on fishing activities with heavier rain and lightning preventing men from going fishing (and causing one fisherman’s death). These response patterns showed that the children’s views were, to some extent, shaped by activities that they frequently observed or took part in, matching common gender differentiations and stereotypes, where women are associated with household and domestic activities while men are mostly associated with outdoor activities such as fishing.

Sea level rise was not seen as significant at this time because it is a slow-onset event compared to shorter heavier rainfall and stronger winds. Sea level rise was perceived to be a feature of future, rather than of current climate change, suggesting that children were both influenced by their own experiences (the inability to detect slight sea level rise) and by other sources. The children’s knowledge was a product of their own personal experiences and a range of other external sources. Many stated that they see, feel, and hear that the climate is changing, and talked about how their schools had, in the past year (2020), been closed a couple of times, due to flooding caused by heavier rainfall. Some children described the rivers overflowing and flooding parts of their lands while others talked about the roads and bridges flooding making them unsafe for vehicles. Observing and listening to stories from other children and people in their families, villages, and churches were other significant sources of knowledge. Their teachers and peers at school were other sources of knowledge, alongside television, radio programs, and community awareness programs by government ministries and non-government organizations such as the Red Cross and ADRA (Adventist Development and Relief Agency).

The children’s responses provided a nuanced understanding of the multiple dimensions of climate change in Samoa, and of their complexity and dynamic nature over time and space. For instance, examining the children’s perceptions of temperature revealed that the northern part of Upolu was perceived to be hotter than its southern part. Previous studies of older age groups in eight other villages across both islands in Samoa revealed similar findings that recognized hotter days and longer dry spells, heavier rainfall, stronger winds, but which also included sea level rise (Latai, 2017; Cassinat et al., 2022; Latai-Niusulu et al., 2020). The study also revealed that children, especially those 10 years old and above, understood and were able to articulate, particularly in their drawings, the holistic and complex nature of the environment and how climate change is a multi-dimensional process. The two images (Figures 7 and 8) drawn by children living in northern Upolu revealed more than one climate change dimension. For example, 10-year-old Edna stated that her drawing (Figure 7) contains pictures of “stormy weather conditions like heavy rainfall, lightning and thunder, stronger storm surges and winds.” Moreover, the images portray how these multiple spatial and temporal dimensions of climate change impact their lives in various ways. Edna not only wrote, but spoke to the researchers about soil erosion caused by higher waves, strong winds, and flooding. In the same way, 15-year-old Natu in her explanation of her drawing (see Figure 8) spoke about future climate change such as rising temperatures causing plants to wither and die and heavier rainfall causing flooding and erosion.

Other studies of children’s perceptions of climate change conclude that children mostly learn about climate change in schools and by watching various media reports (Berse, 2017; Gautam & Oswald, 2008; Jabry, 2003). This was also mentioned by the Samoan children. However other sources of knowledge for children in Samoa, predominantly their own experiences, account for perceptions being different in different parts of Upolu. Significantly, many children developed their awareness through directly experiencing these changes, as they experienced their village circumstances and engaged with family members. Most children had experienced challenging climate related and other natural disasters. Their experiences of these events helped them imagine and formulate climate scenarios that could take place in the future, as well as envisaging adaptive strategies such as relocation to higher places. Children who witnessed the 2009 tsunami experienced trauma, but demonstrated growth from distress to coping to eventually planning for the future (Latai & McDonald, 2016).

Conclusion

This study examined the perceptions and views of young Samoan children on climate change by directly engaging them in focus group discussions and picture drawing. The findings confirm observations from Asian and other contexts that children, especially those 10 years and above, observe and are aware of the changes that occur in their environments (Berse, 2017; MacDonald et al., 2013). However, the present study also revealed that even younger children were familiar with certain aspects of climate change. Indeed, while formal comparison is impossible, because of different methodologies and time periods, Samoan children appeared to be more familiar with various facets of climate change compared with children in much larger islands and states, whether in the Asia-Pacific region or in Europe (Lee et al., 2020; Ramos et al., 2023) where climate change may seem more distant and global. Samoan children’s discussion of climate change impacts covered various themes related to observation, reception, and comprehension, and recorded some benefits and many challenges from climate change. Even on a small tropical island, children were able to distinguish local variations in climate change and its impact.

Most children were aware of current and future climate change and related impacts. Their perceptions revealed localized climatic conditions, general changes in these conditions over time in their villages, as well as the impacts of these changes on their environments and lives. The children’s responses provided knowledge of current and future climate change that pointed to how climate change impacts places differently and will continue to do so in the years ahead. Responses also indicated how the children related to both media and classroom discussions, but also to their own specific local experiences. This knowledge was informed and developed during play, carrying out chores, and listening to nearby people; it derived from their own lives and family livelihoods and was therefore subtly gendered. That was enhanced by more standard sources of classrooms and the media.

Broadly, the contexts that influence Samoan children are similar to those that affect children of similar ages elsewhere. It is unsurprising that children’s perceptions are similar, or that older children’s perceptions are more subtle and more elaborate, less likely to be simply emotional, but more considered, reflective of problems and linked to possible mitigation strategies. Relocation to higher places is a strategy that some children mentioned and portrayed in their pictures. While the study found few significant gender differences in perceptions of climate change, this was not unexpected where children live in close, small-scale village communities. However, the gendered nature of climate change impacts on children and youth and their perceptions remains under-researched (Babugura, 2016). Nonetheless even on a quite small, but mountainous island significant differences occur and are recognized, alongside age and gender differences.

The children’s experiences of natural hazards, notably the dramatic and disastrous 2009 tsunami, caused them to be more aware of changes occurring around them and their impacts. Where children’s lives are bound up with the natural environment such as they are in the agricultural and fishing economies of Samoa, it is unsurprising that perceptions are particularly influenced by local changes and hazards, as more evidently in more extreme climatic conditions (MacDonald et al., 2013), and by the outcomes of change in everyday livelihoods, hence the gender variations. Equally unsurprisingly, impacts were most evident to children on coastal margins where pressures on human and physical resources are greatest, and marine and terrestrial biodiversity is the most disrupted.

The Samoan children recognized both the challenges of climate change and the possible opportunities it brought. Children can be positive agents of change and listening to and understanding children’s perceptions of climate change renders them more likely to be prepared, potential agents of change in participating in and constructing their own futures. More research is also needed to gather knowledge of children’s coping methods and how these could inform community and national adaptive strategies. Due to limited time, the children were not given enough opportunity to talk about adaptation and their ideas on coping mechanisms, hence this is an area for further research. There is also a need to evaluate existing national climate change policies in Samoa to examine whether they are sensitive to children’s needs. Since this is the first study of children’s perceptions of climate change in any Pacific Island, it would be valuable to undertake comparative studies in other small islands and Pacific states to examine similarities and differences, to reveal how climate change can be differentiated and can impact places differently. While studies are too few to make valid comparisons, there are indications, for example, in the young age of children who are capable of recognizing climate change and the consensus over its key components, that sensitivity to climate change is particularly strong in small island states. There is also need for further research on how children’s views can be given due weight and how that might contribute to policies directed to longer term resilience. That is particularly so in small island states like Samoa with youthful populations where the future impact of climate change is likely to be considerable. It is evident that in different parts of a single small island, children have age-related forms of perception, knowledge, awareness, future imaginings, and agency that need to be considered, embraced, and taken seriously.

Funding

This article is based on research funded by the National University of Samoa.