Introduction

Unlike many of their counterparts in the world’s lower latitudes, small cold-water islands, especially ones located in polar and sub-polar regions rarely attract large numbers of visitors (Baldacchino, 2006; Nilsson, 2008). Harsh weather conditions limit the tourist season to a few summer weeks (Butler, 2006). Given their small populations and limited settlement sizes these destinations lack the economies of scale, finding it hard to entice enough workers to offer the type of tourism facilities and services commonly encountered in warmer zones. Most such islands experience a slow pace of life, often associated with traditional activities like fishing.

Nevertheless, signs exist that cold water islands are no longer the cut-off places of yesteryear. In the age of social media, uploaded selfies on Instagram depicting dramatic scenic backdrops instantly advertise some of the world’s remotest regions (Ioannides, 2019). Several islands have become popular stopovers for cruise ships owned and operated by multinational specialist companies (McLeod et al., 2022; Remer & Liu, 2022; Sheller, 2007). In response, these destinations witness the proliferation of mostly small businesses catering to the visitors (e.g., cafés, souvenir stores, operators of adventure tours), which operate on a seasonal basis. Unsurprisingly, large scale accommodations for overnight visitors are rarely found in these destinations given the seasonality and smallness. However, the growing popularity of local homes and rooms on Airbnb and other online peer-to-peer accommodation platforms has added tourism capacity to cater to increasing demand from international markets. Since Airbnb and companies like it are global giants, their strengthening presence in the supply of short-term rentals coupled with the growing attention that tour operators and cruise companies pay to cold-water islands means that these destinations no longer exist beyond the clutches of the worldwide capitalist system (Jóhannesson, 2015; The Guardian, 2016).

What does the growing influence of globalisation mean for destinations like these isolated cold-water islands? Do these forces threaten their unique traits? In turn, could they ultimately reduce these islands’ attraction as destinations (Nilsen, 2016)? Several authors point to evidence that places are not passive pawns when reacting and adapting to growing signs of globalisation (Aquino & Burns, 2021). Indeed, they often do so by displaying elements of what Shortridge (1996) originally termed “neolocalism,” a phenomenon where local inhabitants react and adapt to rapid changes because of growing exogenous pressures arising from tourism (Ingram et al., 2020).

Here, we seek to identify how neolocal expressions play out in a remote cold-water island. We focus on Heimaey, a volcanic island off Iceland’s southern coast, which is witnessing growing popularity as a cruise destination and has been attracting increasing numbers of overnight visitors. We explore how the proliferation of new tourism developments, especially Airbnb properties, influences people’s sense of localness. Specifically, we investigate whether various types of Airbnbs, ranging from locally run and operated properties to more professionalised services controlled by (mostly) outside interests, exhibit divergent manifestations of neolocalism? If so, what do they entail from a sense of localness perspective? We address these issues through a qualitative case study. Specifically, we thematically analyse the results of in-depth interviews conducted with local stakeholders including Airbnb hosts, business owners, and public officials. Our investigation’s value is that it enriches our understanding of hitherto unexplored, yet increasingly popular neolocal-tourism dynamics (i.e., Airbnb) and their (potential) implications for island communities (e.g., Heimaey) from a sense of localness perspective.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Following the literature review, we describe the case study area, namely the island of Heimaey. Subsequently, we introduce and explain our study method before providing the results. We end with a discussion and our conclusions.

Literature Review

The lure of cold-water islands

Over the last two decades, tourism researchers have paid growing attention to cold water islands (Baldacchino, 2006; Petridou et al., 2019; Prince, 2017; Röslmaier & Albarrán, 2022). This research focus on high latitude destinations, many of which are located in polar and sub-polar regions, coincides with their enhanced association with alternative tourism forms, which attract more adventurous individuals compared to those lured by the sand, sea, and sun in lower latitudes (Butler, 2006).

The drawback of cold-water island destinations is their lack of large-scale tourism infrastructure (Royle, 2004). They often have tiny populations living in small settlements. Traditionally, they have depended on fishing and small-scale farming. Harsh weather conditions restrict visiting opportunities to a few weeks in summer. Because of limited opportunities for rapid tourism development on the scale encountered in warmer climes, “the dynamics of tourism on cold-water islands tend to operate in relation to myths of cultural experiences, adventures and discoveries in line with idyllic conceptions of [mostly] rural landscapes” (Prince, 2017, p. 102). Accommodation establishments tend to be small, options for dining and drinking limited, and few formal attractions exist. Mostly, the draw of these islands’ depends on their natural attractions (e.g., scenic views and abundant birdlife) and opportunities for outdoor recreation. On some island destinations, growing understanding of the opportunities that tourism can generate have led to local initiatives relating to sectors such as crafts, arts, and gastronomy while festivals have also gained popularity (Aquino & Kloes, 2020; Peng et al., 2020).

Neolocal processes are becoming increasingly evident on cold-water islands (Ingram et al., 2020). Before focusing on Heimaey as one such destination, we flesh out the meaning of ‘local’ and ‘localness’ in the context of this study.

Places of Neolocalism

Drawing from Relph (1976), Roudometof (2018, p. 807) argues that “place can be described as a location created by human experiences [and] becomes the raw material for identity construction.” Associating the ‘local’ with a specific place gives the term a distinct identity, elevating its significance vis-a-vis the ‘global’. Thus, to comprehend how globalisation and other forces influence people’s lives, we must also consider people’s connections to specific locales. These connections strengthen our understanding of how inhabitants seek expressions of localism when reacting to changes caused by forces such as tourism.

Within this context, increasing attention has been paid to neolocalism, which refers to “the conscious attempt of individuals and groups to establish, rebuild, and cultivate local ties, local identities, and increasingly, local economies” (Schnell, 2013, p. 56). This concept emerged from the “experiential angst of rootlessness” (Flack, 1997, p. 38) encountered in case studies linking the evolution of microbreweries and local craft beverage production and consumption to a sense of place (Flack, 1997; Shortridge, 1996; Slocum et al., 2018). Flack (1997) maintains, neolocalism is a process through which local stakeholders seek to reinforce a locality’s image by developing and labelling locally-inspired products and experiences as a reaction to threats of globalisation (see also Honkaniemi et al., 2021; Schnell & Reese, 2003). Today, one can find elements of neolocalism expressed, for example, through product labels (e.g., microbreweries, restaurants, clothing, and tourism), which seek to connect the mindset of locals and consumers to specific particularities of places (e.g., historical buildings, natural settings, or events). Such efforts have been shown to strengthen brand loyalty (see Schnell & Reese, 2003).

While critics describe neolocalism as “new wine in old bottles,” what sets this process apart is that it attempts to promote distinguishing local characteristics “through choice, not by necessity” (Schnell, 2013, p. 56). In other words, according to Holtkamp et al. (2016), neolocalism results from the “conscious effort” of local entities “to foster a sense of place based on attributes of their communities” (p. 66) in response to growing demands by tourists to experience elements of a destination’s localness. Unlike sense of place, which refers to “relationships between people and social-settings and human-place bonding with its rootedness, insidedness and environmental embeddedness” (Cavaliere & Ingram, 2020, p. 4), neolocalism is, according to these authors, strongly associated with commercial practices.

It is worth mentioning that despite the excitement associated with neolocalism, critics warn it can lead to severe problems if this approach evolves haphazardly (Cavaliere & Ingram, 2020). In one U.S. community, for instance, the local government’s failure to pursue its neolocalism strategy by adhering to the wishes of a diverse group of stakeholders meant that only the interests of a very small group were addressed (Ingram et al., 2020). Others argue that profit-oriented neolocalism efforts often obscure negative features associated with a destination by reframing unpleasant past events as something positive. This ends up in ‘artificial’ constructions of authentic connections to places (see Honkaniemi et al., 2021). Meanwhile, such attempts to ‘sexy up’ places by (re-)constructing local stories and histories could, according to these scholars, beautify and highlight rather than dispose of unwanted, negative stereotypes.

Since (neolocal) tourism development initiatives might not necessarily adhere to strategic planning, some communities may be overwhelmed by them (Nilsson, 2008). Scholars note that neolocal tourism can create or further exacerbate issues such as overcrowding and, ironically, loss of place identity (Ingram et al., 2020). Such a problem often links to the now well recognised critique that the proliferation of Airbnb rentals and the popular idea of ‘living like a local’ can fuel severe shortages of affordable housing for local inhabitants (Guttentag, 2019). Thus, the lack of clear planning can result in the effects of neolocal tourism on various destinations becoming increasingly similar to those commonly associated with mass tourism (Mody & Koslowsky, 2019).

Airbnb within the context of neolocalism and a sense of localness

On several cold-water islands, the appearance of microbreweries, restaurants promoting local gastronomy, events, and specialised guided tours point to their inhabitants’ growing desire to follow a neolocal approach to tourism as a means of highlighting what is local within their habitats (Peng et al., 2020). Increasingly, this strategy pays off, as Russo and Richards (2016) argue, when locally instigated initiatives succeed in allowing tourists to better immerse themselves in destinations and gain meaningful experiences. Additionally, in many such destinations, the explosion of alternative tourist accommodation options aided through online home-sharing platforms such as Airbnb fills in a notable gap in the formal supply of ‘authentic local’ lodgings.

Despite ample criticism levelled towards online peer-to-peer short term accommodation platforms, most notably Airbnb (Guttentag, 2019), this accommodation form highlights yet another force fuelled by the neolocal movement in these off-the-beaten-track places. Russo and Quaglieri Dominguez (2016) contend that Airbnb and similar companies allow ever-more demanding tourists to access ‘local’ housing in remote places, which is “socially produced (easily accessible from everyday communication and professional platforms) and trustworthy (provided and/or evaluated by peers)” (p. 16). As Mody and Koslowsky (2019) argued, companies like Airbnb allow new ways for visitors to “immerse themselves in destinations and the kinds of experiences they have while there . . . These new tourism experiences increasingly leverage a societal trend towards neolocalism” (p. 1). After all, people’s homes can serve as a proxy to what it means to be ‘local’. Thus, just like other elements of neolocalism, Airbnb reflects a reaction to locals’ and visitors’ growing tendency to deeply immerse themselves in their own home-turfs and destinations through tourism that facilitates meaningful experiences of what it means to live and be there.

Certainly, not all Airbnb accommodations dovetail with the characteristics of neolocalism. Indeed, in most destinations there is more than one type of Airbnb depending on, for example, on who owns and manages rentals, the motivations of the owners, and the degree to which owners and guests interact. At one end of the spectrum there are homeowners who either rent space within their own home or a second home (e.g., a summer cottage) purely to supplement the household income and, often, as a chance to meet and interact with new people (Guttentag, 2019). In such cases, Airbnb tends to be a side-business. These casual Airbnb owners are ones who provide an element of neolocalism by facilitating host-guest interactions. Chances to interact increase when the guests share the same home with their hosts and their families (Adie et al., 2022; Röslmaier & Albarrán, 2022). At the other extreme, many destinations move towards so-called professionalised Airbnb services, which usually entail a single entity owning and managing multiple properties entirely for the short-term market (Ioannides et al., 2019). In these cases, the motive is mostly to maximise profit. These so-called professional Airbnbs rarely, if ever, highlight the destination’s localness. Their hosts almost never engage meaningfully with the local community and guests via direct contact (Röslmaier & Albarrán, 2022).

We should add that the Airbnb company has expanded its offerings beyond the supply of short-term rentals. For instance, “Airbnb Experience” is a product where locals, some of whom happen to be homeowners, offer services highlighting various aspects about their homeland (Airbnb Experiences, n.d..). These activities include culinary experiences, storytelling, and specialised tours, all of which fit the description of neolocalism (Schnell, 2013). However, Mody and Koslowsky (2019) suggest that a problem associated with the uncoordinated appearance of neolocalism, in particularly, cases of local homes being completely transformed into short-term rentals, could result in visitors intruding even more excessively in the lives of locals and thereby threaten their sense of localness.

According to Black (2016), sense of localness relies on community members who “share a sense of affinity in recognising what is local culture [and that they] predominantly source products and processes associated with a community of place, directly linked to the individuals and groups who reside, work, and participate in that place” (p. 175). Initiatives like microbreweries, but also Airbnb serve as showcases of localness and authenticity of production, of “cultural traits that are increasingly valued by consumers and used to perform … distinction” (Miller, 2019, p. 124). Often, Airbnb listings draw on elements highlighting a destination’s character, connecting to its history, and legacies (e.g., its fishing tradition) (Airbnb, n.d.; Mathews & Picton, 2014). It is here where the concepts of sense of localness and neolocalism intersect. Through Airbnb, hosts can highlight certain narratives of places through naming, labelling, storytelling, and artefacts that reflect, among others, places of origin, local culture and identities, or, in other words, a sense of localness.

Thus, we suggest that neolocal-tourism/Airbnb dynamics both rely on and highlight the localness of production and sense of localness and it is this local embeddedness that intimately entangles them with identity formation (Miller, 2019). One way to investigate these entanglements as they unfold through commercial aspects of neolocalism is to speak to various local actors, including Airbnb hosts, who actively engage in conversations concerning sense of localness and (place) identity formations in terms of both conservation and innovation (see Ahman, 2013; Massey, 1994). At the same time, we find that the literature refers to neolocalism as a commercial tool through which locals can (always) achieve a better, more sustainable outcome vis-a-vis following more conventional forms of tourism practices. The synergies between neolocalism, Airbnb, and sense of localness suggest that neolocalism can be more than a mere tool that not only leads to a positive outcome for small island communities, particularly when branding/commercialisation dictate the ‘rules’ and directions (see Graham, 2020).

Heimaey

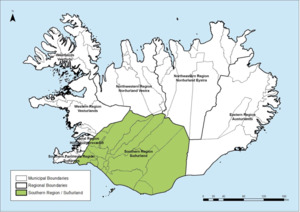

Heimaey (population 4300) is the only inhabited island in the volcanic archipelago of Vestmannaeyjar (Westman Islands) (Figure 1). The archipelago is a small part of the southern administrative region of Iceland. A major volcanic eruption in 1973 forced an evacuation of Heimaey’s population. Inhabitants eventually returned to the island after many homes and businesses were re-constructed. While the fishing industry remains Heimaey’s major economic sector, the island has witnessed a rapid growth in tourist arrivals, a phenomenon, which mirrors recent events throughout Iceland (Jóhannesson, 2015; Röslmaier & Albarrán, 2022).

Reasons leading to the growth of tourism on the island include improved ferry services to the Icelandic mainland. Also, several cruise companies visit Heimaey during the summer season. A beluga whale sanctuary was developed by Merlin, a British multinational entertainment company. Additionally, the island has a museum and an aquarium while several local entrepreneurs have established visitor-oriented businesses like tour companies, cafés, a microbrewery, art-galleries, and gourmet restaurants. Home-hosting activities like those provided through Airbnb Experiences (e.g., dinner parties with storytelling) have become increasingly popular. While the formal accommodation stock on the island is limited to a handful of small lodgings (i.e., a small hotel and a few guesthouses), the expanding number of Airbnb listings has increased the number of bed spaces (Röslmaier & Albarrán, 2022).

Until the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, the number of arrivals was increasing on Heimaey (Stjornarradid, 2020; Vegagerdin, 2016). Despite this growth, however, Heimaey is still referred to as Iceland’s “best kept secrets” (VWI, 2020), a label stemming from locals’ efforts to preserve their history, engage in local storytelling, and continue their traditions. One such tradition involves organised efforts to rescue puffins, which become disoriented because of light pollution. Nowadays, tourists are invited to participate in these so-called “puffin patrols.” Additionally, locals have long descended cliffs to collect puffin eggs. This activity has now also evolved into a local sport (VMI, 2019). While such activities boost Heimaey’s reputation as a destination, there are signs that parts of the community, notably its downtown, have not escaped forces of global tourism exhibited through the proliferation of cruise arrivals and the multinational-funded whale sanctuary.

Methods

We followed a qualitative case study approach where the purpose is to gain an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon through interviews with local actors (Creswell, 2013). The concept of neolocalism suggests that to understand the neolocal-tourism dynamics, one must first consider the views and opinions of different stakeholders who practice neolocalism in a community (Ingram et al., 2020). Moreover, in our literature review we suggest that a sense of localness in tourism can be best observed by studying the expressions, practices, and performances of host communities. Since local actions and practices such as neolocalism and sense of localness tend to be intrinsically linked to a particular geographic location and specific points in time, it is crucial to follow an approach that helps to understand “a specific case in all its particularity… from within and from the perspectives of the people involved in the case” (Renfors, 2021, p. 516).

Before we go deeper into our methods, we should mention that this research is part of the main author’s larger investigation of new tourism’s transformative capacity in small community settings. Thus, we extracted the relevant information for this study, which the main author gathered during a 3-week stay on Heimaey in the summer of 2019. While on the island, the main author resided for one week at a time with three different Airbnb hosts. He did so to understand the role tourism plays in how these hosts implement, promote, and perform localness in the case of home-hosting activities and what localness means to Heimaey’s inhabitants.

Each day, the main author traversed the island, either alone or accompanied by his respective hosts. Occasionally he participated in organised tours to attractions and observed how local guides (including Airbnb hosts) interpreted their localness. These efforts led us to identify activities that are commonly associated with neolocalism such as local beer brewing, events and festivals, arts and crafts, and storytelling.

The main author recorded his observations through fieldnotes, videos and photographs for several reasons. First, these data revealed visible aspects of embedded neolocal activities in the local landscape (Gual et al., 1986; Russo & Richards, 2016). Second, such information helps scholars to identify potential interviewees and adapt the guides of semi-structured interviews in order to dig deeper into the stories behind the activities, practices, and performances observed (ibid.). Last, according to Saunders (2011), observations, videos, and photographs can also be crucial for analysing interview accounts since they can help make better sense out of the meanings behind different local practices (e.g., exhibitions, storytelling, building styles, and products for sale) and how they, eventually, come to the fore.

The main author’s first interviews were with his three respective Airbnb hosts. Subsequently, he identified an additional 32 study participants through snowball-sampling (Krippendorf, 2013). Eventually, the main author interviewed public officials (2), business operators (11), public-sector employees (5), two local experts (i.e., a historian and a representative of the local destination management organisation) and other islanders (12) who happened to be directly or indirectly involved with neolocal-tourism dynamics. Although data saturation was reached prior to completing all interviews, the main author wanted to honour everyone’s eagerness to participate in this study. As it happened, the last two interviewees were useful in helping us broaden our understanding of Heimaey.

Every person chosen for an interview must have lived on the island for several years, ideally before tourism’s growth began in 2008. This criterion was important to draw out and connect changes to the interviewees sense of localness to certain (neolocal) tourism developments. The interviews were conducted in English and averaged an hour. The shortest was about 45 minutes while the longest lasted approximately 90 minutes. We asked our interviewees about their feelings concerning tourism’s growth in Heimaey. They were encouraged to talk freely about what they saw as the benefits associated with this growth, but also to describe their fears as to the damage that tourism causes to their identity, local traditions, and sense of localness. Besides, they were asked to reflect about current Airbnb dynamics and what they mean to them. They were also asked to provide examples, descriptions, and perceptions of ‘localness’. Eventually, the respondents discussed how tourism shapes their daily lives, businesses, their experience with tourism so far, and their feelings toward Heimaey as their home. Every study participant volunteered for this study after they were fully informed about the nature and purpose of the research. Furthermore, they were informed that their answers would be treated confidentially and that they could, at any time, withdraw their consent to participate in this study.

Following the transcription of our interview data, we studied each text multiple times to identify elements that were most relevant to this paper’s main topic. This process was aided by using the qualitative analysis software Dedoose, which helped us organise the interviews and follow a rigorous coding approach. In turn, each code was analysed, refined, and combined into a broader group of themes, which we believe best reflect the study participants’ perspectives. According to Stoffelen (2019), thematic analysis requires scholars to systematically examine and interpret qualitative data whether they follow a deductive or inductive approach. For this paper, we followed an inductive approach since the emphasis is on discovering patterns and themes that emerge out of our data that we can later make sense of with the help of academic literature (Patton, 2002).

Results and Analysis

Three distinct themes emerge from the interviews. The first addresses how locals use neolocalism to portray their perception of the island’s tourist identity. The second focuses on examples of neolocal expressions through which locals project ‘localisms’. The Airbnb sector emerges as a central vehicle of neolocalism. Specifically, different types of Airbnb hosts follow varying neolocal strategies to interpret and promote their perceptions of being local and the extent to which they seek to ensure that their interpretations match potential customer expectations of ‘the local’. The third theme reveals and dissects the conflicting attitudes of respondents towards the presence of different types of Airbnb experiences on Heimaey. It also explores how hosts struggle to find a healthy balance between conserving and innovating ‘localness’ and how they construct and promote ‘localness’ to locals and visitors alike.

Theme 1: Conveying a ‘sense of localness’ through neolocal tourism

Interviewees generally agree that tourism’s growth in Heimaey has begun to diversify the island away from its reputation as a traditional fishing settlement. The island has become livelier than ever before, partly due to the appearance of symbols of neolocalism like high-ranking restaurants and a microbrewery. Locals strive to identify ways to turn tourism into a creative channel to retain and project the island’s identity. Their ideas draw from the island’s unique historical and geographical elements.

One interviewee explained how the island’s volcanic nature inspired the creation of a ‘volcano’ museum commemorating the volcanic eruption of 1973 while the local microbrewery lists its ‘volcano beer’ as its most famous product. The volcano’s importance to the island’s residents was also highlighted when the same interviewee mentioned how locals can bake bread on the volcano’s upper reaches.

My grandma used to make bread, which I call lava bread … Today, some 46 years later, the only place that is still hot and allows you to bake bread or bake fish … is on top of the volcano… Did you taste our volcano beer at our new brewery? … using our volcano for something positive has become a very famous and special thing… something both locals and tourists enjoy. (Local guide)

Such initiatives show that locals managed to turn the volcano, despite its negative connotations, into something positive and ‘cool’ to experience. Dulse, a type of red seaweed, which defines the unique flavour of the popular local ‘volcano beer’ was once an important part of Icelanders’ diet (Local entrepreneur). According to some interviewees, its use has reminded locals that dulse is something unique and a typically local ingredient that “everyone who visits us should experience” (Local guide).

The volcano’s popularity as well as other natural features are also themes highlighted by several Airbnb hosts who wish to convey to their visitors their version of Heimaey’s meaning.

When I decided to open this up as an Airbnb, I decided to have every room different… Your room I call it lava room. It is the only room that has a view over the volcanos and the lava… something that is unique and local… Another room I call Puffin Room, with pictures [and in colours] of puffins. I can see that depending on in which room people stay, they become very much interested in the theme of the room. (Airbnb host 2)

The islanders’ desire to assert their identity has not obstructed changes from occurring. The puffin themed room reflects the popularity of these birds as a visitor attraction but also reveals that locals now refrain from hunting what was once regarded as a staple in the local diet. Thus, unlike in the rest of Iceland, it is almost impossible to find puffin served in Heimaey’s restaurants “because it wouldn’t be perceived very well by our kind of tourists” (Local expert). The main author witnessed this attitudinal shift towards puffins first-hand while participating with one of his Airbnb hosts in a so-called “puffin patrol.” Not only are tourists given the opportunity to participate in these rescue operations, but they also end up volunteering in the puffin rescue centre.

Volunteers… this kind of tourism makes us really proud! … It’s more about the soul. People here feel very connected to place and the environment. Tourism helps us to remember… our traditions, our history, nature [that help us to] keep this place special. (Employee of local attraction)

Nevertheless, interviewees also stressed that while they see benefits associated with the neolocal-enhanced tourism on the island they worry about the danger of their island becoming overrun by tourism.

It is nice that things feel again more alive here, but we should not lose ourselves in tourism… We have to find a balance to offer tourists what they want and keep the things that define us, like our traditions like [e.g., climbing mountains to collect bird eggs], fishing, and so on. These things give us the feeling of being Westman Islanders…. different and special… this is what I believe attracts tourists and us to us… to this place. (Employee of local attraction)

Some islanders perceive that over-reliance on tourism can threaten Heimaey’s uniqueness. One concern relates to the signs of growing exogenous ownership of attractions like the aquarium and the enhanced Airbnb control by outsiders.

Theme 2: (Re)defining and promoting the local and localisms through Airbnb

On Heimaey we find that, at one end of the spectrum, there are certain casual hosts who rent out just one room in their own home and interact closely with their guests. At the other end are the more (semi-)professionally run Airbnbs where individuals, sometimes ‘outsiders’, operate (often) multiple, standardised rooms and/or entire properties with varying degrees of interaction with their guests (see also Röslmaier & Albarrán, 2022). While some of these hosts try to have a certain level of in-person contact with their guests, others never interact with them. Thus, these different styles of Airbnb display differences on how they promote localness to the visitors.

One casual Airbnb owner displays little need to drastically adapt her properties since she believes that this helps her to preserve her own sense of localness, which she can then ‘package’ as something ‘authentic’ for their guests to experience.

When our oldest moved out we thought it is a good idea to make our own library… Then we got the idea to rent this room out on Airbnb but decided to leave our library where it is. I think it is a unique room… It gives people the impression that they just live in an ordinary house that is our house… and [with these books] they can learn more about us and the island… It is not like we need the money. (Airbnb host 1)

This is an example of an Airbnb encounter where locals, ‘by choice’ rather than by what the market dictates to remain competitive, reflect upon local culture by incorporating ‘typical’ local resources and identities (see also Black, 2016; Schnell, 2013). This interviewee further points out that guests, against all their expectations, find their library room ‘cool’. “These books,” they continue, serve as ‘subtle’ and ‘cool’ reminders of local identities and history, and help them to retain, develop, communicate, and eventually share their authentic connection with locals and local places (see also Honkaniemi et al., 2021). “You know, when guests come to us to ask us to tell them more about what says in this book…it is such a nice feeling” (casual Airbnb host). For example, inquisitive guests occasionally asked questions that this host could not answer straight away, prompting the latter to do some research to find out more about Heimaey.

[The guests] wanted to… know more about the island and how life is here. Everybody in my family was like wow … [All of us] had the chance to tell their own story… Everyone realised that there is a lot more to this place than we thought. (casual Airbnb host)

In this case we witness a neolocal-tourism dynamic that helps certain hosts better understand who they are, how they want to define the local, and what they, eventually, want from tourism, but also from living and working in Heimaey.

Furthermore, these findings show that commercial neolocalism relies heavily on visual materials and labels that emphasise a ‘regional touch’ to connect locals and tourists to place particularities (Schnell & Reese, 2003). Yet, our data suggests that it is less the room’s name or the decorations that are the most impactful factors. Rather, the real ‘neolocal element’ and value of the experience occurs is when hosts and guests get the opportunity to build and share a common sense of place and localness with one another. By leveraging the opportunity to share a meal with guests, the host can narrate ‘local’ stories by focusing on specific themes that correspond to the curiosity raised in debates and conversations between hosts and guests. It is through this interaction where the host is sometimes reminded of “who we are, our history with this island, and what this place means to us” (Casual host).

This ‘neolocal’ approach stands in sharp contrast to the belief held by the more ‘professional’ hosts who feel that in today’s tourism market it is ‘necessary’ to ‘innovate’ the ‘local’ and package it as experiences with which they can differentiate themselves from ‘other’ Airbnb listings. In other words, these hosts follow neolocal practices for the purpose of “standing out from the rest here” (Airbnb entrepreneur). This approach differs from the casual host example where neolocalism helps them to better integrate themselves with the community and place and “stand out from other places, like Reykjavik” (Casual host). However, we also find that such ‘differentiation’ attempts of ‘professional Airbnb hostings’ rarely stem from close and personal host-guest interactions. Rather, on Heimaey, they revolve around a ‘careful’ selection of elements that tell a very particular story of ‘localness’.

The outer appearance is pretty much the same… [the colour reassembles a] typical Westman Island house… every room in this house represents a [typical local] theme… like the volcano room… most people here have a personal relationship with the volcano… but that is as personal as it gets… It is a middle-way to keep some memories but also not to give an unprofessional impression. People feel like home, it is clean and not too much into their face. (Airbnb host 2)

This host stressed that the idea behind theming rooms is to reduce the tourists’ potential misconceptions of Heimaey’s localness. This is why he chose topics that, from this perspective, best reflect the island’s ‘authentic’ characteristics like its unique geology, birdlife, and colours of the sunrise and sunset. At the same time, because this choice is partially a response to tourism demands, he raises concerns about his own sense of localness, accepting that finding the right balance is difficult to achieve. On the one hand, he wishes to convey something authentic about the property (in this case ensuring that the house itself retains the character of a traditional island home). On the other hand, he refrains from displaying anything personal (e.g., family pictures). Thus, unlike the ‘casual Airbnb host’, this ‘semi-professional’ host attempts to construct a sense of localness’ based on a combination of ‘professional practices’ in the name of ‘innovation’ and ‘casual practices’ in the name of ‘preservation’ (see Massey, 1994). In both cases, (i.e., the casual and semi-professional Airbnb properties), locality becomes the raw material and main ingredient for identity construction and preservation (see Roudometof, 2018). This, in turn, can contribute to the goal of achieving a shared affinity in recognising what is ‘local’ (Ingram et al., 2020).

Theme 3: Finding a balance between (identity) conservation and (tourism) innovation

These approaches adopted by the casual and semi-professional Airbnb hosts differ sharply to those witnessed in Heimaey’s more professional Airbnb properties. For instance, we noted the tendency to invest heavily on luxury elements in such Airbnbs because some hosts believe this niche will improve their business’ competitiveness. Moreover, one developer mentioned “we all want something unique, something special… a taste of luxury.” According to many interviewees, however, such tourism-dictated desires must not replace “historically significant” aspects of the ‘local’ that they consider “worth enough to preserve.” This is best illustrated by one person’s reaction to the planned lighthouse’s conversion into a luxurious Airbnb.

[This] is… one if not the oldest buildings here. This place has a very important meaning for us. It was kind of central for this island, for the fishing industry…and our survival… it was always run by the same family for many generations… Places like this lighthouse not only have a shell…they have a soul. (Local resident)

Fundamentally, this interviewee is concerned that the conversion of the lighthouse – one of the island’s most important landmarks – into an Airbnb will compromise local preservation efforts for the sake of promoting tourism. In fact, our data reveals that the lighthouse, perhaps even more importantly than the volcano, functions as both the genuine ‘local’ but also the touristic highlight of Heimaey. Many interviewees speak of the lighthouse as the “most beautiful,” “historical building,” marking one of Heimaey’s most “unique locations.” The lighthouse is situated in an area, which offers shelter to the “beloved puffins,” essential nutrition for the “famous Westman Island sheep” and a “peaceful environment” where many locals gather for picnics and whale-watching. Inside the lighthouse itself, people find a “typical lighthouse” and “traditional interior” that reminds locals of stories of “life in the old days.”

Thus, it is obvious that many locals fear that the transformation of the lighthouse into an Airbnb ends up compromising the very identity and soul of this place. In their eyes, the lighthouse, becomes degraded into a mere touristic theme. It conveys a story told by hosts who otherwise have minimal connection to and knowledge about the place and the community.

That is why I prefer people like these [casual Airbnb hosts] because they know and want to show everyone what this island means to us. Everyone here knows them, and they know they don’t just have Airbnb to make money… they use this [Airbnb] as an opportunity to promote this place… us… the way things are. They know how things work here… the culture… everything. (Public official)

This person reflects a common belief among respondents that locally owned and managed Airbnbs aimed at generating additional household income as opposed to those which are full-time businesses are far more likely to authentically promote the island’s localness. Conversely, she strongly condemns professional Airbnb properties, many of which are owned and managed by outsiders. She believes that exogenously controlled Airbnb experiences project limited or no understanding of Heimaey, its people, and history.

Thus, most interviewees agree that the biggest challenges for neolocalism in tourism on Heimaey is to convince (Airbnb) developers of the merits of immersing themselves more fully in the local community and history so that they can promote an authentic ‘sense of localness’. According to the interviewees, this requires developers to be open-minded, to communicate, and cooperate with locals.

These concerns, however, are not limited to the Airbnb phenomenon, as one interviewee highlights:

You live here on Iceland’s most famous fishing place, and you cannot buy fresh fish…this place [previously the only, traditional, local fish-shop] closed because they couldn’t afford the rents anymore… instead you get all these Airbnbs, the big Aquarium, a brewery… people with money… [but before] everything was a lot more… authentic. Things become more about big business now… about following global trends. (Local resident)

This interviewee reflects the controversies surrounding some neolocalism-tourism dynamics. Specifically, she regards the transformation of the downtown, iconic buildings (e.g., the lighthouse) and traditional localisms (e.g., fish shop) into commercialised tourist places as actions that detract from the island’s localness. Even neolocal expressions like the microbrewery and handful of gourmet restaurants can be regarded as reflections of globalised tendencies resulting in transforming countless areas into tourist bubbles (Ioannides et al., 2019). Ultimately, this and several other interviewees fear that in Heimaey local vestiges once associated with the island’s identity are slowly eroding away.

Discussion and conclusions

Overall, neolocal establishments such as high-ranking gourmet restaurants, a microbrewery, and Airbnb rentals are vehicles through which local inhabitants on Heimaey seek to redefine their identity and sense of localness. Thus, the island once narrowly associated with its fishing industry, has been diversifying in recent years through a tourism-oriented ensemble of initiatives driven both by locals and outsiders. The latter include a small number of global investors. Meanwhile, puffin and volcano themed accommodations, volcanic bread-baking and beer brewing, as well as puffin patrols are initiatives that exemplify ideas and identities of ‘the local’, which according to the interviewees are often based on idyllic conceptions of local landscapes (see also Prince, 2017). Furthermore, these particular commercial neolocal practices constitute attempts to associate the ‘local’ with a specific place and its respective background story. According to the literature, this process can potentially elevate the significance of the ‘local’ vis-a-vis the ‘global’. It also positions localisms as a necessary stepping-stone towards reviving sense of place, community, and sense of localness (Holtkamp et al., 2016; Russo & Richards, 2016). While such neolocal expressions are evident in several Airbnb properties on the island, the strategies used by the hosts of such properties and their outcomes vary depending on both hosting styles (i.e., casual, semi-professional, professional) and their objectives.

On the one hand, there are locals whose principal aim in owning and running an Airbnb to supplement family income and who primarily wish to use the platform to interact closely with their guests. In these cases, the guests live in the same home as the host families, share meals with them and listen to their stories. This implies that the hosts act as gatekeepers of local knowledge (Adie et al., 2022). These hosts believe that by offering their guests the experience of staying in an authentic and ordinary Icelandic home, both parties can share a sense of localness and convey a better understanding of life on the island. Interestingly, this strategy appears to extend beyond the commercialisation that most observers attribute to expressions of neolocalism (Graham, 2020). For instance, most interviewees are adamant that only such properties and experiences can bring forth what Black (2016) terms “a sense of affinity in recognising what is local culture” (p. 175; see also Mody & Koslowsky, 2019; Röslmaier & Albarrán, 2022). In this case, neolocalism is more than a mere commercial expression in tourism. It becomes a channel through which casual Airbnb hosts can highlight and share their perception of ‘ordinary life’ on the island and their personal relations with various localisms. They do so through a dynamic and adaptive form of storytelling that is tailored to and co-constructed through various guest-encounters. In such cases, the outcomes of such encounters are hard to foresee, to replicate and, subsequently, to commercialise. In that sense, the form of neolocalism encountered in casual Airbnbs is deeply entangled with individual expressions of sense of localness. In other words, it appears that this form of neolocalism, much like sense of localness, can be perceived as an experiential and creative cultural process that accompanies rather than constitutes conventional, standardised commercial tourism practices (e.g., formal accommodations, microbreweries, and gourmet restaurants).

On the other hand, there are the business-minded semi-professional hosts who stage their properties with elements inspired by local history and nature in response to their perceptions and, perhaps, misconceptions of what the tourists might desire in their search for local and authentic experiences. As our findings suggest, this response is not always one such hosts make by choice (see Schnell, 2013) but because they feel it is necessary in an increasingly competitive market (i.e., commercial orientation). For instance, we noted that the semi-professional host who included a puffin-themed and a volcano-inspired room in his property seeks to highlight what he refers to the island’s major tourist attractions. Thus, this host’s sense of localness becomes deeply entangled with neolocalism as a function of commercialisation. At the same time, this example suggests that neolocalism is also more than just a reaction to perceived threats of losing what sets a place aside from others in the advent of globalisation (see Flack, 1997). After all, puffins and volcanoes are not ‘unique’ features associated solely with Heimaey. Yet, because they are ‘tourism best-sellers’ such ‘global’ features are used to define localness via a platform (i.e., Airbnb) that itself is truly global (Mody & Koslowsky, 2019). This suggests that the more professionally inclined hosts selectively hybridise and camouflage elements of localness, globalisation, and commercialisation, usually with the purpose of gaining a competitive advantage regardless of whether the outcome reflects Heimaey’s uniqueness and their own ‘sense of localness’ (Mathews & Picton, 2014; Miller, 2019). It is also here where the question arises whether such a dynamic, where sense of localness is constructed through neolocalism for purely commercial reasons as exemplified through the Lighthouse-Airbnb case, can on its own convey the islanders’ feelings of localness to their guests.

In general, these findings suggest that it is up to individual hosts to decide to what degree they (commercially) infuse the experience with unique and ‘typical local’ elements and their personal ‘sense of localness’ and to what extent they package the experience as a response to globalisation processes. We find that one major difference is that the more professionally inclined Heimaey’s hosts are, the likelier they appear to offer an ersatz (neo)localness. This entails reducing neolocalism and ‘sense of localness’ to superficial representations in terms of appearances, names, and labels rather than projecting the community’s shared affinity in recognising what links ‘local features’ to both individuals who work, reside, and participate in Heimaey, and ‘unique’ place-based localisms. In responding to their preconceptions of what their guests demand, some ‘future Airbnb hosts’ justify the employment of ersatz neolocalisms by stressing the need to identify a niche for economic survival. They do so, for instance, by incorporating and highlighting luxury, even if that means they must ‘artificially package’ the ‘local’. Their actions are guided by global tourism standards that, ironically, makes some of them worry about losing their own sense of localness. Thus, centring (sense of) localisms in Airbnb experiences through commercially initiated strategies like neolocalism does not necessarily translate into a more sustainable outcome for a community as a whole as commonly suggested in the neolocalism literature (see Graham, 2020).

Despite the apparent contrasts of these Airbnb-neolocalism dynamics, they share one significant commonality. That is, they all illustrate local desires to actively engage/motivate debates and conversations concerning place identity via constructing and/or reviving senses of localness. On the one hand, the casual hosts highlight their ‘sense of localness’ by falling back on elements of Heimaey’s ordinary life and occasional references to the island’s natural and historical assets. We interpret this as conscious efforts to conserve and convey (place) identity and sense of localness. In many respects, neolocal practices emerge from and through guest ‘encounters’ (i.e., co-constructing localisms and ‘sense of localness’). In the case of the more professional hosts, on the other hand, we find that ‘sense of localness’ is constructed for neolocal practices and neolocalism for rather than through guest encounters. Here, neolocalism becomes deeply intertwined with, sometimes even dictated by, innovative strategies as hosts, often unconsciously, reduce neolocalism to be a pure commercial substitute. In turn, this might explain why many scholars tend to refer to neolocalism as (mere) commercial practices of labelling, naming, and theming. As suggested by Roudemetof (2018), such practices run the risk of undermining rather than elevating the significance of the local vis-a-vis the global. From a sense of localness perspective, this means that the current Airbnb dynamics on Heimaey raise the residents’ awareness of localisms, but also complicate the interviewees’ affiliations with place and community.

Our findings question the commonly held idea that neolocalism is a mere commercial tool through which locals can (always) achieve sustainable outcomes that counter the increasing influence of globalisation, standardisation, cosmopolitanism, and tourism (see also Black, 2016; Ingram et al., 2020; Röslmaier & Albarrán, 2022). Instead, we suggest that expressions of neolocalism (e.g., commercial, localness) and their outcomes in terms of sustainability as seen through the various types of activities and Airbnbs encountered in our study are distributed along a continuum. On the one end, we witness neolocal practices like the puffin rescue missions and casual Airbnbs where locals rely on ordinary rather than (commercialised) ersatz localisms in order to conserve a sense of localness, which they wish to conserve and, as such, convey to their guests. On the other end of the continuum are the professional Airbnb hostings that, similar to more conventional neolocal activities (e.g., microbreweries), pre-select elements in terms of ersatz localisms that convey a particular, innovative and profitable sense of localness for targeted tourist markets.

Final thoughts and suggestions for further research

This study demonstrates that in spite of Heimaey’s remoteness, keeping the forces of globalisation entirely at bay is impossible, despite the appearance of neolocal activities (Flack, 1997; Honkaniemi et al., 2021; Schnell & Reese, 2003; Shortridge, 1996; Slocum et al., 2018). It is, however, important to note that this finding does not necessarily undermine the desire of many local inhabitants and other stakeholders, as exhibited by several existing (Airbnb) initiatives, to highlight their perceptions of localness not just for the sake of the visitors but also themselves. The core problematic is that these initiatives appear to be fragmented, the results of actions by individuals or single businesses, which do not appear to follow a concerted strategy for the entire island. This points to the necessity for close dialogue between Heimaey’s stakeholders (e.g., destination developers, policymakers, entrepreneurs, and inhabitants) with the aim of creating a targeted strategy for the island that recognises tourism’s contribution to overall sustainable development.

A central aim of such an effort might be to distinguish between elements that convey a ‘true’ sense of localness vis-a-vis those that reflect ersatz manifestations of localism. Furthermore, our findings suggest that neolocal-enhanced tourism developments like Airbnb can lead to sustainable outcomes when they support local endeavours to highlight localisms that, from their perspective, convey a (shared) sense of localness. According to this study, this would require a careful and coordinated effort that seeks to avoid the pitfalls seen in numerous destinations whereby locally-inspired efforts are eventually moulded by the trends of the global (tourist) market.

Ultimately, this study demonstrates the conceptual and practical intersection between tourism (especially expressed by Airbnb), neolocalism, issues of sense of localness, and sustainability. Despite evidence of ‘true’ (non-commercial) expressions of localism through the informal Airbnbs, there appears to be a growing tendency that these are becoming overshadowed by their commercially oriented counterparts. In the case of Airbnb on Heimaey, we find that both approaches to neolocalism stem from inhabitants’ living spaces whereby hosts and guests (co)construct (ersatz) localisms in the name of conservation or innovation. In this process, we find that the boundaries between the local(isms), the global, and cosmopolitanism are blurred, thus complicating people’s sense of localness. Thus, we argue that even by adopting neolocal practices, cold-water island communities remain increasingly torn between accepting and seeing new tourism dynamics “as a passport to development [or] a threat to local culture and traditional life” (Nilsson, 2008, p. 97). In the end, this raises questions about neolocalism’s ‘taken for granted’ contribution to sustainability.

Certainly, there is a need for more in-depth research, especially from a comparative standpoint, to understand the implications of these dynamics for social sustainability and community resilience on islands such as Heimaey. We also suggest that future studies move beyond the prevailing presumption witnessed in existing literature that neolocal tourism activities, both conceptually and in practice, are mere substitutional, commercial tools through which communities will, somehow magically, attain sustainable outcomes.