1. Introduction

The entrepreneurs’ journey is long and uncertain. From the moment entrepreneurs identify a business opportunity until the formal creation and management of a firm, they must overcome several challenges. A successful entrepreneur needs to identify an opportunity, develop the concept, assess the required resources, acquire the necessary resources, and, in the end, manage and harvest the venture (Morris & Jones, 1999). Within this process, entrepreneurial motivation is critical to comprehend entrepreneurs’ cognition, intention, and action (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011). William Bygrave (2009) defines the entrepreneurial process as involving “all the functions, activities, and actions associated with perceiving opportunities and creating organizations to pursue them;” and of the entrepreneur as “everyone who starts a new business … the person who perceives an opportunity and creates an organization to pursue it” (p. 2).

The link between entrepreneurship and spatial context is well established in the literature. It is seen as fundamental to the emergence, development, and outcome of an entrepreneurial activity. Given the fact that “entrepreneurs do not exist apart from resources that they bring and hold in their firm, their personal characteristics or their environmental context” (Juma & Sequeira, 2017, p. 92); it is only natural for geographical environment to have a significant impact on entrepreneurs’ motivation, behaviours, and actions. As posed by Wigren-Kristofersen et al. (2019), entrepreneurship is an embedded activity, which will have different disclosures depending on the context. Welter (2011, p. 165) added by stressing that it is important to better comprehend “when, how, and why entrepreneurship happens and who becomes involved.”

In the literature islands are identified as possessing a unique set of geographical conditions. According to Baldacchino (2015) an island is “a community whose life depends totally on the sea … [being] constructed – economically, environmentally, socially, politically, culturally – by the water that surrounds it” (p. 38). The economic context of islands is intimately entangled with history, culture, and social cohesion (Burnett et al., 2021). The specific conditions of islands create several challenges in the development of entrepreneurial activity (Baldacchino & Fairbairn, 2006). In this matter, Briguglio (1995) underlines that the two major restrictions faced by remote islands are small size, and insularity and remoteness, in addition to stressing that “not all islands are remote, but remoteness renders the problems of insularity more pronounced” (p. 1619). Therefore, the development problems faced by small island regions can be compared to the problems faced by peripheral or remote rural areas (Baldacchino, 2005).

Madeira, a remote island, which is an outermost region (OR) of Europe, was selected to conduct this study. ORs are perceived as different because they have several constraints upon their socio-economic development, such “remoteness, insularity, small size, vulnerability to climate change, and economic dependence on a few sectors” (European Commission, 2022). According to Ismeri Europe (2011), these regions have not fully benefited from the single market and globalisation due to a lack of critical mass, “different extents, protection, rigidities, imperfect mobility of factors and extreme remoteness” (p. 8). In the specific case of Madeira, the region was able to grow in the last decades because it has benefited from financial transfers, mass tourism, hosting an offshore financial centre, and attempting to delay the adverse impacts of globalization as much as possible (Almeida, 2008). Analysing the development of remote islands, such as Madeira, in light of regional development theories, it is perceivable that these regions face significant difficulties promoting growth. However, sectors such as tourism, biotechnologies linked to biodiversity and natural resources, energy projects, and high added value services in the health sector and tourism development are perceived as having high potential (Ismeri Europa, 2011).

Entrepreneurship research has gained in importance in the last two decades. Many researchers have focussed their attention on the entrepreneur, individual, or a team, the entrepreneurial process, entrepreneurial ecosystem, or even international entrepreneurship. Most empirical research is conducted in developed countries and core regions with the objective of ascertaining the so-called conventional paths of the entrepreneurship phenomenon. Even though islands present an intriguing, and, therefore, interesting context for the study of the entrepreneurship phenomenon, “relatively little has been written on enterprise and entrepreneurship on islands where problems tend to be different, additional and exaggerated” (Burnett & Danson, 2017, p. 25). Given the limited research on entrepreneurship on islands (Baldacchino & Fairbairn, 2006; Booth et al., 2020; Pounder & Gopal, 2021), and because “islands and islandness, whether as metaphors or reality, are important areas of research” (Hall, 2012, p. 180), this study sets out to add to our knowledge of the entrepreneurship phenomenon by analysing islanders’ entrepreneur motivation and actions throughout the entrepreneurial process. Hence, this study addresses the challenge of improving our “understanding of how regional conditions shape individual decisions and developments” (Fritsch & Storey, 2014, p. 946). Additionally, it will also respond to the need for contextualizing entrepreneurship research (Welter, 2011; Zahra, 2007) by taking a closer look at linkages between localities and entrepreneurship (Müller, 2016; Trettin & Welter, 2011). The article will empirically explore “how different contexts enable and constrain entrepreneurs” (Korsgaard et al., 2015, p. 594). Finally, it will offer guidance to help design policy instruments (Fritsch & Storey, 2014). The research also addresses the need for more qualitative research on the study of entrepreneurial motivations (Dawson & Henley, 2012). Moreover, this study will contribute to the limited literature on entrepreneurship in small islands (Baldacchino & Fairbairn, 2006) by conducting an island study from different perspectives and including islander researchers (Baldacchino, 2008). Finally, this type of research is necessary given the fact that conceptual models need to be tested in different entrepreneurial contexts.

Despite recognition of the importance of context for entrepreneurship, our understanding of the linkage between the entrepreneurial process and island context is limited. Hence, following Fritsch and Storey’s (2014) suggestion of improving our understanding of regional entrepreneurship by investigating individual behaviour in its regional context, this study contributes to the literature by conducting an in-depth analysis of the influence of the regional context on journey of entrepreneurs, from the initial idea and motivation to the challenges of managing an existing firm. Additionally, this study contributes to our understanding of the character of island entrepreneurship, a requirement identified by Baldacchino and Fairbairn (2006), who also stressed that there is an important challenge of increasing the number of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial skills on islands.

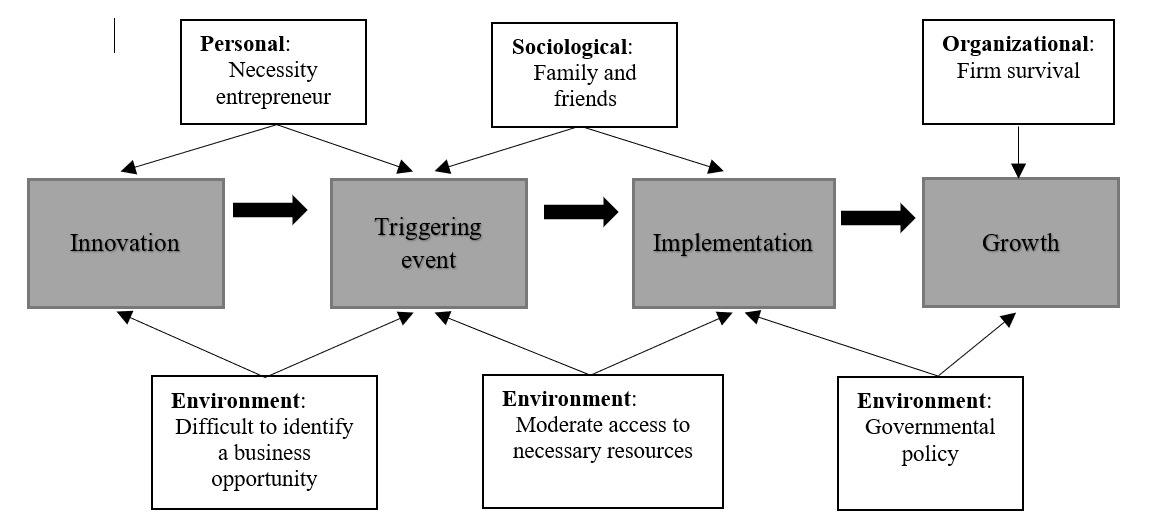

To achieve these goals, the investigation sought to answer an important research question: what characterizes the entrepreneurial process in remote islands? To do so, the study adopted Bygrave’s (2009) four phases of the entrepreneurial process to frame analyse within case studies: (a) innovation, will assess the opportunity identification; (b) triggering event, evaluates if the major motivational factors are push or pull; (c) implementation, determines the most important resources for the firm creation; and (d) growth, regarding the firm’s future. Bygrave’s entrepreneurial process definition and model frame a linear process with very well-defined phase and a clear description of the actions that the entrepreneur needs to conduct in each of the different phases. Therefore, it provides a better operationalisation of theoretical concepts for this study’s context and contributes to a more straightforward data collection process.

2. Theoretical Background

Entrepreneurship activity appears due to a current or potential existence of something new, which appears from new forms of looking at old problems, or new problems that appear from the external environment (Brazeal & Herbert, 1999). Many researchers have identified different steps or actions required for the development of entrepreneurial activity, hence, presenting entrepreneurship as a process (McMullen & Dimov, 2013). The process of capturing new opportunities and bringing them into existence is formed by different phases. As stressed by Liguori et al. (2020) “entrepreneurship is a behavioural process that unfolds over long periods of time” (p. 312). The idea of entrepreneurship as a process has been presented and studied by several authors (e.g., Shane & Venkataraman, 2000).

As it is perceived, the entrepreneurial process is a dynamic interaction between the individual, the entrepreneur, and the contextual environment in which the new venture will appear. For this reason, the entrepreneur’s intentions, motivation, skills, and values are central in the entrepreneurial process (Müller & Korsgaard, 2018). The new firm’s performance will be influenced by individual factors, characteristics of the entrepreneur, and by externalities of the spatial context (Juma & Sequeira, 2017). As posed by Jack and Anderson (2002), entrepreneurs are embedded in the local structure and social context, because “context simultaneously provides individuals with entrepreneurial opportunities and sets boundaries for their actions” (Welter, 2011, p. 165). Korsgaard et al. (2015) define this as the socio-material locality in which entrepreneurship occurs.

Empirical research on entrepreneurship has emphasised the powerful influence of context and that it needs to be taken into consideration when establishing plans to reduce disparities in regional economies (Guesnier, 1994). As posed by Fritsch and Storey (2014) “the emergence of new businesses is a development process at the individual and the regional levels” (p. 948). Hence, geographical environmental conditions will be extremely important to the development of entrepreneurial activity, and it will also help explain the entrepreneurial disparities between countries and between regions within the same country. Kibler (2013) highlighted this idea by stating, “individual perceptions of entrepreneurship and the formation process of entrepreneurial intentions are shaped by the ‘objective’ regional environment within which an individual is embedded” (p. 310).

2.1. Remote Islands and Entrepreneurship

Several studies have shown that regional context significantly impacts entrepreneurial activity by enabling or constraining the activity due to the number of available resources (Korsgaard et al., 2015); affecting its performance and sustainability (Juma & Sequeira, 2017); and influencing entrepreneurs’ behaviours (Welter & Smallbone, 2011), attitudes and motives (Martinelli, 2004). In this context, regions that have a high availability of resources, market size, and even an encouraging entrepreneurial culture, may be expected to have more dynamic entrepreneurial activity when compared to less privileged regions. Consequently, the geographic location and small size place remote islands in a disadvantageous position (Selwyn, 1978), creating a challenging environment for entrepreneurial activity. Additionally, the development of certain economic activities in these regions, principally in the manufacturing sector, will be extremely problematic (Winters & Martins, 2004) because of high transportation costs and the difficulty in obtaining economies of scale (Krugman, 1991). Islands will also face other difficulties, namely, limited labour market, small domestic market, and limited economic interaction (Sufrauj, 2011), in addition to inadequate access to technology and investment capital (Baldacchino, 1999).

Given the specific characteristics of small islands, “there are several constraints to traditional forms of economic development” (Booth et al., 2020, p. 1). Within the literature, islands are perceived as possessing four main characteristics: (a) boundedness (bounded by spatial limits), (b) smallness (in terms of land area, population, resources, and livelihood opportunities), (c) isolated (distant from other land areas, people, and communities) and (d) littoral (coastal areas) (Kelman, 2020). These regions face extra constraints upon their economic growth associated with transport and communication (Read, 2004), which will translate into higher transportation costs, uncertainty of supply, and logistical problem (Briguglio, 1995). Additionally, remoteness increases the propensity to “internal market imperfections, because producers are not subject to effective competition” and make these regions apart “from the centers of power where decisions affecting them are made” (Srinivasan, 1986, p. 213). Therefore, remoteness affects everyday lives of island residents, in their work, education, leisure, transports, politics, culture and weather conditions (Burnett et al., 2021), and “isolation is commonly seen as an inevitable companion of islands” (Ronström, 2021, p. 279). Hence, islands are perceived as a risky venture for foreign investment, which limits opportunities of international trade (Bojanic & Lo, 2016).

Entrepreneurial activity in remote islands is challenging. Rytkönen et al. (2023) argued, “Islands constitute a specific type of business context, frequently described in terms of their remote location and often peripheral status, the characteristics of island culture and geography” (p. 239). Firms created in small island territories will face limited linkage to the local economy, lack of local business knowhow, and a scarcity of quality support and infrastructure services (Baldacchino, 2005). Studies in the Pacific Islands have shown that local entrepreneurs face problems regarding the lack of entrepreneurial tradition and entrepreneurial skills, prevalence of an economic structure dependent on subsistence agriculture, low status of entrepreneurship as a career option, inefficient government policies, problems in obtaining external investment capital, and an underdeveloped financial sector, with a limited number of commercial banks (Baldacchino & Fairbairn, 2006). In this matter, Pounder and Gopal (2021) recognize “that in most islands, a collectivist culture exists and as such, goals of the entrepreneur align with social obligations rather than a focus on profit” (p. 417). Wennecke et al. (2019) have also identified that entrepreneurship in small communities is mostly driven by community values. Baldacchino and Fairbairn (2006) stress that, on islands, the availability of entrepreneurs is weak given the fact that islanders do not have the skills, motivation, and desire to risk, rather they tend toward intrapreneurship by innovating within existing organizations.

Nevertheless, being an island is not always a bad thing for business. Burnett et al. (2021) stress that remoteness in an island can constitute a considerable economic leverage, especially within the tourism sector, because it positions “the experience of islandness as distinctive and different” (p. 3). Booth et al. (2020) conducted a literature review on tourism and hospitality entrepreneurship on islands and identified that the industry is restructuring through islands transitioning to a service economy with tourism in a prominent role. Mitropoulou and Spilanis (2020) found, “The change of the global context in recent years, where locality and special features have taken on more importance, these same characteristics of the islands have been transformed from disadvantages to potentialities to be explored” (p. 35). Additionally, government can contribute to a more dynamic entrepreneurial context (Gnyawali & Fogel, 1994), especially in the case of remote islands, by promoting instruments to attract investment and develop supporting services and infrastructures. As a result, government policies will impact entrepreneurial activity and entrepreneurs’ motivation because they “mold institutional structures for entrepreneurial action, encouraging some activities and discouraging others” (Minniti, 2008, p. 781).

2.2. The entrepreneurial process in remote islands context

In this section, we combine the entrepreneurial process with the limitations and restrictions of their context on islands context, as previously presented, to highlight how these limitations may constrain the behaviour of entrepreneurs. Bygrave (2009) presents a model of the entrepreneurial process, based on Carol Moore (1986), divided into four different phases (innovation, triggering events, implementation, and growth), influenced by three critical factors (personal, sociological, and environmental). The process begins with the innovation phase, the stage where idea generation for new products or services occurs and business opportunities are identified. The entrepreneur’s task is to study the environment to discover, evaluate and explore entrepreneurial opportunities, which will be dependent on asymmetries of information and beliefs (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). In the regional context of islands, there is a limited access to information (Beer, 2004), which hinders entrepreneurs by decreasing the availability of information to the entrepreneur, which suggests that on islands it will be more difficult for entrepreneurs to identify business opportunities, the only exception being on the tourism sector. Recent data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM, 2023) has shown that in some island countries, such as Cyprus, the percentage of adults who identify good opportunities to start a business in their area is low.

Bygrave (2009) poses that “there is almost always a triggering event that gives birth to a new organization” (p. 4). This phase is related to events that generate the decision to create an organization, the firm. It also includes the assessment of resources, risk, and funding. An example of a triggering event can be not having better career prospects, a promotion having been passed over or even having been laid off or fired (Bygrave, 2009). Therefore, a triggering event can be the main motivation that encouraged an individual to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurial motivation has attracted the attention of many researchers, and several empirical studies identified various motivational factors, reasons for entrepreneurs to start their businesses, namely: autonomy, making money, desire to exploit a market opportunity, frustration with previous job, frustration with career, desire to innovate, actual or threatened redundancy, making use of skills that have been acquired, social mobility, and resistance to geographical mobility (Cromie, 1987). Other scholars add self-realization, recognition and roles to this accounting of the motivation of entrepreneurs (Carter et al., 2003; Cassar, 2007). Several conceptual frameworks emerged to explain the motivation to become an entrepreneur. Push and pull theory (Mueller & Thomas, 2001; Williams et al., 2009) has become increasingly dominant in entrepreneurship literature. Push theory argues that people are pushed into entrepreneurship by negative situational factors. Negative events, they contend, “tend to activate latent entrepreneurial talent and push individuals into business activities” (Gilad & Levine, 1986, p. 46). Hence, push factors are the negative factors that drive individuals to become entrepreneurs, such as dissatisfaction with existing employment, loss of employment, or career setbacks (Brockhaus, 1980; Shabbir & Gregorio, 1996). These are the necessity entrepreneurs. Pull theory suggests that the “existence of attractive, potentially profitable business opportunities will attract alert individuals into entrepreneurial activities” (Gilad & Levine, 1986, p. 46). Pull factors are the positive factors that pull or encourage individuals to become entrepreneurs. Several empirical studies have identified the following pull factors: entrepreneurial activity in childhood, having one or more family member with entrepreneurial experience, and identifying business opportunities (Carroll & Mosakowski, 1987; Krueger, 1993). These are the opportunity entrepreneurs.

According to Dawson and Henley (2012), the pull and push factors in entrepreneurship are divided into internal or external factors. Regarding external factors, the push factors are lack of alternative opportunity, redundancy, and lack of resources. Pull factors are the abundance of resources, market opportunity, and innovation. This suggests that conditions in the spatial context surrounding individuals influence their willingness to become entrepreneurs. Therefore, the entrepreneurs’ perception of the scarcity or abundance of critical resources within a region is a crucial element in their decision to create a new firm (Begley et al., 2005). As posed by Hessels et al. (2008), “the nature of the environment in terms of hostility, munificence, and dynamism will impact on entrepreneurial motivation” (p. 328). As a result, island entrepreneurs are expected to be more motivated by push factors than pull factors. In this matter, studies have showed that islanders are drawn into entrepreneurship by the need to provide cash for families and the necessity of control (Baldacchino & Fairbairn, 2006), and to earn a living because jobs are scarce (GEM, 2023).

In the implementation phase, entrepreneurs strategically design the execution of their business idea through the elaboration of a business plan and the control of the necessary resources. The literature identified several resources or factors that can help entrepreneurs to create their firm and seize entrepreneurial opportunity, namely: help from family and friends (Davidsson & Honig, 2003), role model of other successful entrepreneurs (Tamásy, 2006), social network (Greve & Salaff, 2003), business background experience (Westhead, 1990), supportive government programmes and fiscal incentives (Choi & Phan, 2006; Dana, 1990), low legal requirements (Dana, 1990; Fogel, 2002; Klapper et al., 2006), easy access to capital (Evans & Jovanovic, 1989; Pennings, 1982; Sutaria & Hicks, 2004), and technical assistance and supportive services (Dubini, 1989; Fogel, 2002). In the case of small islands, Rytkönen et al. (2019) studied the role of context in entrepreneurial response in Sweden and concluded that institution, tradition, habits, and social capital are crucial factors.

As understood, spatial context poses several opportunities, threats, and challenges to potential entrepreneurs, in addition to providing the necessary resources for the development of their entrepreneurial activity, thus playing a crucial role in its success or failure. Therefore, it can be argued that island context will make it more difficult for entrepreneurs to access the resources necessary for the creation of a new firm, however, this reality can be overcome. Entrepreneurs surpass the challenge of islandness by building a “collective capital, strong networks, and the capability to learn from and respond/adapt to a changing environment” (Rytkönen et al., 2019, p. 84). Leick et al. (2023) conclude that island entrepreneurs can compensate for the lack of resources by establishing a local embedded network of higher degree and quality. Additionally, in this phase public economic policy can directly influence the entrepreneurial process by facilitating the access of island entrepreneurs to important resources throughout supportive programmes (e.g., incubators) or financial incentives (taxes reduction). As underlined by Levie and Autio (2008) “through dedicated support programs, governments can facilitate the operation of entrepreneurial firms by addressing gaps in their resource and competence needs” (p. 242).

The last phase of the entrepreneurial process is essentially linked to growth. Entrepreneurs will harvest earnings, work to see the business grow, and prepare for the future. Entrepreneurship literature emphasises that new firms will be directly influenced by their locality, their survival being dependent on their adaptability and ability to maximise entrepreneurial efforts within a specific environmental setting (Aldrich & Martinez, 2001), and control of the necessary resources (Pfeffer & Salancik, 2003). Box (2008) argued, “It is obvious that firms, new or old, do not exist in a vacuum; firms interact with their environments, and these environments provide both opportunities and constraints” (p. 381). In the case of islands, Williams et al. (2020) underline that despite the negative influence on growth of the external condition, firms are able to “survive through various aspects of close relationships within their stakeholder set” (p. 953). Nevertheless, the survival capacity of firms in island will also be influenced by entrepreneurial motivational factors; pulled entrepreneurs will have better post-entry performance (Mohan, 2019), while pushed entrepreneurs are associated with less business, financial, and strategic skills to guarantee business survival and expansion (Mohan et al., 2018).

3. Methodology

A multiple-case study methodology was chosen to conduct this research for two reasons: (a) to offer a better guideline to mainstream economic theory regarding entrepreneurship in island territories (Baldacchino & Fairbairn, 2006); and (b) for being more compelling and robust, and allowing the study of a “contemporary phenomenon in its real-life context” (Yin, 1994, p. 13). To ensure the quality of study design, Yin’s (1994) recommendation to maximise construct validity, internal validity, external validity, and reliability was followed. The next section describes how these recommendations were applied in the case study design.

3.1. Case Study Design

The multiple-case studies are based on entrepreneurs’ experience on creating their firm, which emerged from the literature review. The first data source, and the most important, was the in-depth semi-structured interviews with entrepreneurs. It had a common structure to ensure that interviewees addressed the same issues, being exclusively formed by open questions. These interviews were conducted between November and December of 2010. The firms’ websites were used as a second source of information to obtain complementary information on entrepreneurs and their firms (history, location, and others). This helped overcome problems of bias, poor recall, and articulation. Cases were analysed using pattern-matching, which helped clarify some key aspects of the entrepreneurial process and relate it to the literature review. To ensure the study’s reliability and to minimise errors and biases, case study protocol was developed, and a case study database was created.

Case Selection

The criterion sampling method (Patton, 2002) was used. Cases were identified from a group of entrepreneurs that had previously partaken in a standardized survey about entrepreneurship in their region and were willing to participate in an in-depth follow-up interview. Replication logic was also used with the following criteria: a) location, island of Madeira, (b) sector of activity, the manufacture of medical and dental instruments and supplies (Manufacturing), the travel agency, tour operator reservation service and related activities and amusement and recreation activities were chosen (Tourism), and the business services of legal accounting, book-keeping and auditing activities, tax consultancy (Business Services), (c) firm size, the firms had to have less than 10 employees, and (d) firm age, the firms selected had to have been created 20 or less years. Following the criteria, a total of 8 entrepreneurs, which were also the firms’ general managers, were selected to conduct the case study. Three in the tourism sector, three in the business service sector, and two in the manufacturing sector. According to Eisenhardt (1989), between 4 and 10 cases will be sufficient to conduct a multiple-case study, therefore, the cases selected are adequate to reach theoretical saturation. Regarding the spatial context, Madeira presents an environment where the true value of entrepreneurship can be observed (Kodithuwakku & Rosa, 2002), and where the new firms “can be said to constitute critical or extreme cases where both the enabling and constraining forces of spatial context can be expected to be clearly visible” (Korsgaard et al., 2015, p. 581).

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of firms in the case study, regarding sector of activity, year of creation, and number of full-time employees. It also presents the social and demographic characteristics of the entrepreneurs interviewed regarding gender, age, nationality, education, previous work, and years of experience.

In 2021, entrepreneurs were contacted again by email with the purpose of gaining their feedback on the firm’s performance in the last decade and on the firm’s future. Of the eight entrepreneurs contacted, three had closed their firm in the previous years (Entrepreneur 01, 02, 05); and three responded to our request and provided their feedback (Entrepreneur 03, 07, 08).

Data Analysis

Interviews were conducted in person in Portuguese and lasted between 30 minutes to one hour. They were recorded, transcribed, and then translated into English. Unclear answers were clarified and approved through email correspondence with the entrepreneurs. Data coding and analysis followed the procedures outlined in Miles and Huberman (1994). To improve analysis, existing literature was used to correlate themes and unveil differences. Initial focus was given to the entrepreneur’s experience in the process of creating their firm before comparing results between sectors.

4. Results and Discussion

In this section the results will be presented in accordance with the difference phases of the entrepreneurial process. Table 2 presents the codes identified in the interviews analysis.

4.1. Innovation

The first theme presented to entrepreneurs was regarding the identification of entrepreneurial opportunity. They were asked if in their region it is easy to identify a business opportunity in the sector of activity in which their business operates. Most entrepreneurs referenced that it is not easy to identify a business opportunity, however, all entrepreneurs from the business service sector consider it to be more difficult, contrasting the ones from the tourism sector.

Concerning their own experience, a significant portion of entrepreneurs identified the business opportunity within the sector in which they already work, making use of their background experience and knowledge of the business. Others identified a business opportunity within something that they enjoyed doing.

4.2. Triggering Event

The second topic discussed during the interviews was about the main motivation to become an entrepreneur. In all sectors of activity, entrepreneurs were motivated by both push and pull factors. Other empirical studies have shown that entrepreneurs can be motivated by both factors (e.g., Chu et al., 2007; Orhan & Scott, 2001). There are some similarities between sectors of activity regarding the main motivations for becoming an entrepreneur. The need for a job was the push factor mentioned the most (all entrepreneurs from manufacturing, one from tourism, and two from business services). This is consistent with the findings of other empirical studies that identified the need for a job as an important motivation (e.g., Gray et al., 2006; Orhan & Scott, 2001). Entrepreneur 08 mentioned that “there are a lot of accountants for a small number of firms, and they are beginning a price war; in a few days we will not be able to cover our expenses, it is very complicated.” This sector was described by all the entrepreneurs as a very competitive. Another interesting push factor was the need to legalize the business, which was mentioned by two entrepreneurs. In this matter, Entrepreneur 04 said “we had to legalise the business and pay taxes; it was the proper way and we wanted to do it the proper way … that is why we have insurance, we have everything that is necessary to run a business like this.”

The two pull factors mentioned the most by entrepreneurs as the main reason to become an entrepreneur were the desire for independence and haven identified a business opportunity. This is consistent with the findings of past empirical studies which have shown that important motives for becoming an entrepreneur include the desire for independence (e.g., Del Junco & Brás-dos-Santos, 2009) and the identification of a business opportunity (e.g., Orhan & Scott, 2001). The comparison of the motivation to become an entrepreneur between sectors of activity shows that entrepreneurs from the manufacturing sector only mentioned reasons linked to survival.

Regarding the motivation of island entrepreneurs, Wennecke et al. (2019) concluded that the most valued motivations of Greenland’s tourism entrepreneurs were the opportunity to make their own decisions, to contribute to the development in their hometowns, to create new products, and to pass on values to children.

4.3. Implementation

The third theme discussed in the interviews was the resources necessary for firm creation and the level of accessibility to them. Most entrepreneurs consider access to the necessary capital easy because they used personal savings to start their business or had financial support from governmental programmes, which benefitted half of the eight entrepreneurs. Yusuf’s (1995) studied the critical success factors for South Pacific small businesses and found that local entrepreneurs consider government support critical for their success.

Background experience was also mentioned as a facilitator resource. This is not surprising because three entrepreneurs created their firms in the business sector in which they already worked. Other empirical studies have shown that knowledge gained, the contacts made, and belief in one’s ability to perform the task are important to new firm creation (e.g., Townsend et al., 2010). As entrepreneur 01 explains “I trust my own hands because I know what I can do. If I knew that I would not be able to produce and be responsible for my work, I would not have created the firm.” Help from family was also considered an important resource, identified by two entrepreneurs. This result is consistent with Davidsson and Honig’s (2003) study that found “encouragement from friends and family was strongly associated with probability of entry” (p. 322).

The resources identified as being more difficult to obtain was compliance with requirements or regulation and the lack of support from the sector or from the local authorities. This may be explained by two reasons. First, the fact that these problems were identified by entrepreneurs that have created their firms before 2005. It is not mentioned in the cases of firms being created after that period. In 2005, Portugal implemented legislation to simplify the legal process of firm creation. Furthermore, most entrepreneurs that mentioned this problem recognised that currently the process is much simpler. Finally, half of the entrepreneurs referenced that they did not find any major problems when creating their firms. The absence of major problems at start-up was also mentioned by entrepreneurs in other empirical studies (e.g., Fraser, 2006).

4.4. Growth

The last topic analysed in the interviews regards the firm’s future. Most of the entrepreneurs envision growth in their firms’ future by having more employees, clients, and expanding their business. However, Entrepreneurs 03, 05 and 07 mentioned that they mostly hope to still be in business in the next five years. Additionally, no entrepreneurs are planning to invest in new technologies, showing that these entrepreneurs are not very concerned with technological innovation, which may be a reflection of deficient access to new technologies in remote islands (Baldacchino, 1999), work volume, and/or type of clients. Several entrepreneurs in the tourism sector intend to expand their business through additional services. In the business services sector, Entrepreneurs 06 and 07 desire to increase profitability per client, which reflects the price war identified by most of the interviewees from this sector.

Regarding the feedback obtained in 2021, the first interesting note is that neither of two manufacturing firms selected in our case study are still in business. The other closed firm operated in the tourism sector (entrepreneur 05). Of the remaining five entrepreneurs, three were available to provide their feedback regarding the last ten years, Entrepreneurs 03, 07 and 08.

Entrepreneur 03 mentioned that their business had grown until 2017 and that a large number of new firms appeared. During this period the firm established partnerships with other firms in the tourism sector. However, the COVID-19 pandemic paralysed this activity, forcing their firm to focus on another area of activity, the accounting services, which has helped maintain the firm’s ability to continue operating. Regarding the firm’s future, Entrepreneur 03 does not believe that the tourism activity will resume in the short term, given that much uncertainty remains.

Entrepreneur 07 gave a positive assessment about their firm’s performance between 2010 and 2020 even though they had to deal with problems linked to the financial crises (problem in getting credit and huge bureaucracy), difficulty gaining customer loyalty, and problems in recruiting human resources. The primary mission of the firm was achieving economic-financial balance. The firm’s future is envisioned through an improvement in financial performance and by becoming a reference point in the local economy.

Entrepreneur 08 emphasized that he had a very positive experience. Their business expanded to another location, hired more employees, and substantially increased sales. However, the main problems faced were the lack of payment from clients, which forced changes in client relationship management, monitoring constant changes in legislation/taxation, and, more recently, excessive COVID 19 incentives. In the future, Entrepreneur 08 would like to delegate more responsibilities to employees and have more time to be outside of the office contacting clients.

In general, regarding the last 10 years, entrepreneurs reported positive business growth after the financial crisis until the beginning of 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic affected all businesses; however, it had a more dramatic impact on the tourism sector with a near-total cessation of activities.

5. Main Findings

In this section we will analyse the main results and respond to the research question by characterizing each of the phases of the entrepreneurial process. Figure 1 presents the main characteristics of the entrepreneurial process in a remote island context.

The entrepreneurial process in remote islands is characterized as challenging. In the innovation phase, evidence suggests that the identification of a business opportunity is easier or more difficult depending on the sector of activity. The development of economic activities in the manufacturing sector in remote islands will be extremely problematic (Winters & Martins, 2004) given the high transportation costs and the difficulty in obtaining economies of scale (Krugman, 1991). The fact that none of the manufacturing firms studied remains in business is a strong indication of the difficulties faced by this sector in small and remote islands. However, small tropical islands, like Madeira, have attractive factors for the tourism industry, which could enable entrepreneurial initiatives in this sector (Winters & Martins, 2004). This highly competitive sector of business services makes the identification of a business opportunity very difficult. These results demonstrate that the identification of a business opportunity in remote islands not only depends on spatial context, but also on the nature of the business. Therefore, this indicates that remote islands can take advantage of remoteness and small size, turning these into assets, like the case of the tourism sector, which can invert the negative spatial context. As stressed by Croes and Ridderstaat (2017) “tourism has emerged as the main impetus of growth and jobs and is a major source of foreign exchange for islands” (p. 1453).

More recently, Rojer (2021) analysed the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Dutch Caribbean islands and concluded these regions need to rethink their development models and seize the opportunities provided by new technologies through reforming and transforming local economies to more promising industries like the ones linked to the orange economy. Other studies of Caribbean economies have shown that information and communication technology can become a creative destructive event with the power to revolutionise the existent business models by overcoming the resource constraints faced by these regions (e.g., Pacheco & Pacheco, 2020). Rudge (2021) also stressed that digitalisation provides the opportunity for islands to go well beyond their geographic boundaries by opening new opportunities for innovation. In the specific case of Madeira, the latest official statistical information published shows that between 2017 and 2020 the annual birth of enterprises in high and medium-high technology sectors was about 70 companies. However, in 2021, a total of 141 new companies were born in this sector. This evidence shows that advances in information technologies, prompted by COVID-19 pandemic challenges, are changing the entrepreneurial ecosystem in small and remote island, with a significant impact on the entrepreneurial process, especially, on the innovation phase. Entrepreneurs from remote islands may now identify new business opportunities in sectors which will not be restrained by geographic or physical constraints.

The case study confirms that the leading triggering event is the desire for independence, which is in line with findings from other empirical studies (e.g., Cassar, 2007). However, most of the entrepreneurs in Madeira were more motivated by push factors, namely, the need for a job. The lack of a wage employment and low income has also been identified by Mohan et al. (2018) as a characteristic of necessity entrepreneurs on islands. In the case of Madeira, this situation may reflect the lack of opportunities which pushes individuals to become entrepreneurs showing that spatial context affects the motivation to become an entrepreneur. Individuals in remote islands, characterized as having a disadvantaged spatial context, will be more motivated by negative situational factors to become an entrepreneur. This is a very important finding for the entrepreneurship motivation literature because it shows that the spatial context needs to be included when conceptualizing push and pull theory. This idea is reinforced by Begley et al.‘s (2005) view that the entrepreneurs’ decision to create a new firm will be based on their assessment of the entrepreneurial environment.

In the implementation phase, the most important resources in new firm creation are having the necessary capital, background experience, and knowledge of the business. These resources were also identified as important factors by other island entrepreneurs (e.g., Baldacchino & Fairbairn, 2006). However, entrepreneurs in Madeira also consider support from governmental programmes as an important resource. The resource most difficult to access was coping with the legal requirements or regulations to create the firm. Resource dependence theory and population ecology theory advocate that environmental conditions directly impact the creation of new firms. Looking at the findings, and as was expected, the entrepreneurs in the remote island studied perceived that they operate in a less favourable regional context. These results provide empirical support to both theories because remote islands’ spatial context does not possess all the conditions, resources, and other organisations to help promote entrepreneurial activity. The findings contribute to the literature by showing that this situation is not evident in all the sectors of activity, which confirms other empirical studies (e.g., Winters & Martins, 2004). Additionally, the findings show that the implementation phase is not influenced by location, given the fact that the most important factors and major problems in this phase are similar in other regional contexts (e.g., Freitas & Kitson, 2018). This is also similar between different sectors of activity, which confirms Michelacci and Silva’s (2007) findings. As a result, researchers need to take into consideration both the location and nature of activity (the sector) when conceptualizing entrepreneurship on remote islands.

Regarding the growth phase, in 2010, most entrepreneurs hoped to grow in the next five years with more employees, more clients or by expanding their businesses. Ruane’s (2007) study of small business entrepreneurs in the Philippines found that “the most commonly cited business plans in the next two years are introducing new product or service and expanding the scope of current activities” (p. 16). However, three entrepreneurs in Madeira mentioned that they hope to still be in business, showing survival concerns. Data collected in 2021 demonstrated that this was a real concern. Resource-based theory advocates that firms will obtain competitive advantage when they attain resources which are valuable, rare, and not easy to imitate or substitute (Barney, 1991). However, how is this theory applied in regions with limited resources? A logical conclusion is that only a very small number of firms will be able to seize these resources, which will put all the other firms at risk of failure. This study demonstrates that entrepreneurs in remote islands will have a smaller pool of resources to choose from and, considering the resource-based theory, this will detract from their ability to obtain a competitive advantage to ensure the survival and growth of their firms. Spatial context influences new firm growth. As a result, long term growth of an entrepreneurial initiative in remote islands is dependent on the innovative capability of firms. This situation mandates that firms need to increase their network in national and international innovation centres and scale their businesses by looking to new markets outside their geography. This might be accomplished by investing in e-commerce. Finally, the growth phase of firms on small and remote island may also benefit from advances in information technologies because “technological transformation has cut down distance and isolation” (Rojer, 2021, p. 130). Therefore, local firms will have the opportunity to access new resources and markets more easily than before, which will increase their probability of survival.

6. Conclusion

This study contributes to the literature by identifying key characteristics of the entrepreneurial process on remote islands. It also presents both managerial and political practical implications. Two important managerial implications are identified, which can assist island entrepreneurs in their decision to explore entrepreneurial opportunities. Future entrepreneurs must focus on the following important factors when deciding to create a firm: access to capital, background experience, and knowledge of the business. They also need to be prepared to overcome problems regarding the legal compliance and taxation.

Regarding the political implications, this study emphasises the important role that governmental policy can play in promoting entrepreneurship in remote islands. As underlined by Levie and Autio (2008) “through dedicated support programs, governments can facilitate the operation of entrepreneurial firms by addressing gaps in their resource and competence needs” (p. 242). Consequently, two important policy implications are identified. First, to help pull new entrepreneurs into the economy, governments need to pay special attention to the promotion of entrepreneurial education, at all levels, thus, encouraging a more risk-taking and achievement-driven society. This is especially important on remote islands given historical migration flows and the necessity to develop local human resources to promote entrepreneurial activity. These findings support Pounder and Gopal’s (2021) study, which shows that low spending on education and technical support on small island developing states represents a less dynamic educational and entrepreneurial system.

The second implication is regarding the growth strategy that should be followed by remote islands. Regarding the specific case of Madeira, Leite et al. (2021) emphasize that it is an emerging innovators region, with “significant delay in terms of innovation, entrepreneurship and R&D” (p. 23). Their study analysed the regional innovation environment on the OR of Europe by examined the 2021 European Union Scoreboard, having concluded that Madeira is 38.5% behind, compared to the EU average. The only two indicators where Madeira is above the EU average are trademark applications and above average digital skills. In three indicators, Madeira is below 20% compared to the EU average, namely, PCT patent applications, R&D expenditures, and employment knowledge-intensive activities. Also, this study’s findings have shown that island entrepreneurs expressed a lack of propensity for innovation. Additionally, governments need to create conditions to take advantage of globalisation to follow innovation trends (Baldacchino, 2005), modern information and communication technologies (Baldacchino & Fairbairn, 2006), and ecological modernisation (Stratford, 2008) by privileging local culture (Burnett & Danson, 2017). This poses a serious challenge for these regions given the “times of unprecedented change related to the ongoing digital transformation of business and society at large” (Trischler & Li-Ying, 2023, p. 3). For all these reasons, governments on remote islands should contribute to an increase in the entrepreneurial capability of local firms by promoting their interaction with international and national network of universities and research centres. They should also develop educational programmes to improve entrepreneur’s strategic, technical, and managerial capabilities for the digital transformation, in addition to promoting fiscal incentives to help firms innovate. As posed by Broome et al. (2018), island governments need to identify policy instruments to help local business sectors access the funding necessary for R&D investments though subsidies or tax credits.

This study faces two major limitations. The first is related to the timing of this investigation. Most data collection occurred in 2010, during a global economic crisis, when the government in Portugal imposed severe measures to control public deficits, which impacted the lives of individuals and firms. Nevertheless, recent data was added, and the goal of this study was accomplished. The second limitation is regarding the specific context of the study. Madeira is a remote island, however, it is part of the European Union and has beneficiated from specific development funds, which have positively contributed to the region’s level of development.

In the end, “islands hold us captive, but they are also captivating” (McMahon & Baldacchino, 2023, p. 1). This research will continue to investigate the nature of entrepreneurship on remote islands. Additional studies are needed to investigate the entrepreneurial process in other remote islands in other geographical locations to test the findings of this research. Also, more data should be collected on the entrepreneurial process from other sectors of activity, thus, contributing to a more holistic view of the entrepreneurial process on remote islands. There is also a need for more information on the islandness effect on entrepreneurs’ intentions and motivations, and on the contribution that women entrepreneurs have for the development of entrepreneurial activity on islands. Finally, new research needs to study the impact of recent economic transformations, specifically, the impact of the fourth industrial revolution, on the entrepreneurial activity in small and remote island.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express her gratitude to the two reviewers who helped improve the quality of this work through their insightful comments.