Introduction

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a framework of 17 discrete goals that make the fuzzy concept of sustainable development more tangible and actionable (Lopez-Claros et al., 2020). A substantial body of work examines the potential co-benefits and synergies, as well as trade-offs, across the 17 goals (e.g., Lim et al., 2018; Lusseau & Mancini, 2019; Markkanen & Anger-Kraavi, 2019; Nilsson et al., 2018; Santika et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2018, 2021). To be successful, however, the goals need to be interpreted and enacted by decision-makers at the national, subnational, and local levels (Lopez-Claros et al., 2020). This means that the goals need to be interpreted as meaningful and actionable by decision-makers and broader publics (Hilson & Maconachie, 2020; Horn & Grugel, 2018; Szetey et al., 2021; Tandrayen-Ragoobur et al., 2021). Thus, research on social interpretations and governance issues helps us better understand the challenges and possibilities for SDG implementation (Randall, 2021).

We undertake a comparative analysis of SDG interpretations and perceptions of SDG governance in Iceland and Newfoundland using surveys and focus groups with stakeholders from government, business, labour, civil society, academia, and youth. Iceland and Newfoundland and Labrador share North Atlantic geographies with small populations that are concentrated in their respective capital regions (Reykjavik and St. John’s). They both traditionally relied on fisheries economies, but have seen an emphasis on economic diversification, including a turn to nature-oriented tourism in recent decades (e.g., see Stoddart et al., 2020). Both regions have been subject to economic boom and bust cycles, including most notably the 2008 financial crisis in Iceland and the recent financial crisis in Newfoundland and Labrador (Stoddart et al., 2021). As such, issues of economic sustainability would appear to be highly salient in both regions. They can also both be characterized as small polities and island jurisdictions (although the Labrador part of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador is on the mainland).

At the same time, there are important differences. Iceland has successfully developed geothermal power, while Newfoundland and Labrador remains highly dependent on the oil sector, meaning there are different tensions involved in managing economic and environmental dimensions of sustainability. Iceland is an island state with the jurisdictional powers and international relationships of a national government. By contrast, Newfoundland and Labrador is a subnational region of Canada that has more limited provincial jurisdiction, albeit in a decentralized and federalist political system. As such, the regions have different capacities for implementing the SDGs.

Our research questions are as follows: First, how do research participants view the SDGs in relation to ensuring sustainable futures for their respective regions? Second, how do research participants view the roles of government and other institutions in implementing sustainability in policy and practice?

In answering these questions, we gain insight into a third theoretically valuable question about SDG implementation: Is it the state versus subnational jurisdiction distinction, or is it the common small polity/island dynamics of these cases that appear to be important for understanding the interpretations of the SDGs and their implementation? Despite some substantial differences, the interpretations of regionalizing and localizing the SDGs are surprisingly similar across our two cases. This offers support for a small polity or “islandness” (e.g., Baldacchino, 2010; Brinklow, 2013; Randall et al., 2014) explanation for how the SDGs are interpreted as locally salient.

Literature Review

Our analysis contributes to the growing social science literature on SDG implementation and social interpretations. Several researchers provide analyses of the synergies — or co-benefits — and trade-offs across the different SDGs, for example between SDG goals for climate action, inclusive development, reducing social inequality, or ensuring ecological integrity of oceans (Lim et al., 2018; Lusseau & Mancini, 2019; Markkanen & Anger-Kraavi, 2019; Nerini et al., 2019; Nilsson et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2018). A focus on synergies and trade-offs is particularly important in relation to oceans and coastal societies — including islands — because of the complex overlapping jurisdictional issues involved in environmental governance and management across onshore, inter-tidal, near-shore, and offshore zones that touch on areas as diverse as fisheries, biodiversity protection, oil and energy development, nature-based tourism development, and ocean health in relation to climate change (Andrews et al., 2021; Nilsson et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2021).

In their analysis of SDG co-benefits for Small Island Developing States (SIDS), for example, Singh et al. (2021) find that 11 of 17 of the SDGs have co-benefits for promoting the health and ecological wellbeing of oceans. Conversely, putting the “oceans goal” (SDG14: Life Under Water) at the centre of planning would help make progress towards a range of other SDG indicators. However, creating marine protected areas or limiting overfishing may have near term trade-offs with other goals (e.g., SDG1: No Poverty; SDG8: Decent Work and Economic Growth; SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities) if they are not pursued in ways that “tightly couple environment, society, and economy” (Singh et al., 2018, p. 229). Others highlight the possibilities to use local tourism development to advance the SDGs in island societies. Grilli et al. (2021), for example, find that as SIDS cultivate sustainable tourism, there are co-benefits that make progress towards multiple SDGs. This includes protection of coral reefs and other natural habitats (SDG14: Life Under Water), as well as urban planning that protects cultural heritage (SDG11: Sustainable Cities and Communities).

Localizing the global agenda is necessary to connect the SDGs more effectively with regional needs and capacities (Horn & Grugel, 2018; Szetey et al., 2021). In their meta-analysis of literature on SDG interactions, Bennich et al. (2020) find that most research has focused on policy integration and coherence. There is a need for more research on how the SDGs are contextualized at different geographic scales, as well as more attention to the diverse “actors responsible for implementing the SGDs” (Bennich et al., 2020, p. 12). Attention to how the SDGs can be strategically localized is important because this provides opportunities to integrate local knowledge, to address social barriers of “scepticism in top-down planning and change,” and to increase the chances of successful implementation (Szetey et al., 2021, p. 16). Conversely, public opinion in favour of the SDGs can nudge government policy responses and thereby address sustainable development gaps (Tandrayen-Ragoobur et al., 2021). As such, it is important to study the varying interpretations among decision-makers and publics regarding perceived trade-offs and synergies between the different SDGs, as well as priorities among the SDGs, all of which may be influenced by regional or local social dynamics (Horn & Grugel, 2018; Szetey et al., 2021; Tandrayen-Ragoobur et al., 2021).

A global view without considering local interests can obscure the tensions across SDGs, which can be difficult to reconcile at the level of regional or local policymaking, such as between ensuring energy access (SDG7) and climate action (SDG13) (Adenle, 2020; Tàbara et al., 2020). However, by attending to the local level we see how innovation involving entrepreneurs, NGOs,and other stakeholders might create “win-win” micro-solutions that simultaneously help ensure community energy security and low-carbon energy transitions (Tàbara et al., 2020). These win-win innovations can also provide social support and help diffuse “transformative” narratives that challenge forms of climate inaction that are rooted in economic anxieties (Hinkel et al., 2020). Similarly, Adenle (2020) examines the uneven uptake of solar energy development in Ghana, Kenya, and South Africa. He concludes that solar energy development has the potential to reconcile competing demands for expanding community energy accessibility (SDG7) and climate action (SDG13) in ways that are locally relevant.

Our analysis also contributes to island studies. Many cold-water islands, including Iceland and Newfoundland island, share similar histories of natural resource dependency, with traditionally fisheries-oriented economies (Stoddart et al., 2020). The recent turn towards experiential alternatives to mass tourism have seen cold-water islands pursue tourism development as an economic diversification strategy, based on the combination of unique natural environments, recreational amenities, and cultural and historic experiences (Baldacchino, 2006). Both islands in our analysis have relatively low population densities with a dominant capital city (Reykjavik and St. John’s) and have struggled with issues of out-migration and youth retention from rural regions (Antonova & Rieser, 2019; Ommer, 2007). Other qualities attributed to islandness include tendencies towards distinct social identities and political cultures (including tendencies towards “island nationalism”) that relate to the geographical and economic challenges of separation from continental mainlands (Vézina, 2014).

Islandness — often characterized by relatively small polities — may also influence political cultures, including the need to skilfully navigate between global political currents and local interests and relationships (Baldacchino, 2010; Randall & Boersma, 2020; Russell et al., 2021; Thorhallsson, 2002). Lévêque (2020) argues that a political culture of personalism characterizes the small polities of islands, regardless of whether they are small states or subnational jurisdictions. Personalism is marked by several characteristics including strong direct connections between politicians and their constituents, as well as a political culture where ideological differences between political parties are less important than the strong personalities of individual party leaders. Personalistic polities are further characterized by a “ubiquity of patronage” relationships within government and across government and the private sector, such that the boundaries between public life and the private sphere are often blurred (Lévêque, 2020, p. 156).

As Russell et al. (2021) find in their multi-island comparative study, there is often a disjuncture between viewing local and regional political institutions as vitally important for managing island life, coupled with high levels of dissatisfaction with — and feelings of disengagement from — many of those same institutions. Looking at the islands of Mauritius and La Réunion, Tandrayen-Ragoobur et al. (2021) similarly find that the translation of the SDGs into policy and practice is impeded by dissatisfaction with island government institutions and public perceptions that those institutions “are not working, or perhaps lack sufficient levels of autonomy or funding, towards achieving the SDGs” (p. 314). Whatever progress these island governments have made towards the SDGs has not substantially shifted public perceptions of “persistent [social] disparities and inequalities” in these island societies (p. 321).

In this section, we have reviewed literature on local-regional interpretations and translation of the Sustainable Development Goals, as well as relevant literature from the area of island studies. Our survey and focus group data analysis bridges these literatures by examining stakeholder interpretations about the SDGs and their views about governance for SDG implementation in the comparative context of two island societies: Iceland and Newfoundland. By comparing interpretations of the SDGs and sustainability governance across these North Atlantic sites — one an island nation, the other a sub-national island jurisdiction — we gain insight into the social-political dynamics of SDG translation in the unique contexts of island settings.

Methodology

This analysis is part of a multi-team project, Sustainable Island Futures, which examines interpretations of — and relationships among — multiple dimensions of sustainability, including how the SDGs are interpreted at regional and local scales (Randall, 2021). The project includes 12 case study teams working across six small island states (Cyprus, Grenada, Iceland, Mauritius, New Zealand, Palau, and St. Lucia) and six subnational island jurisdictions (Guam, La Réunion, Lesbos, Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, and Tobago). Our analysis focuses on the small island state of Iceland and the subnational island of Newfoundland, which is part of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador (NL). We mention the broader project to note that case study teams adopted parallel approaches to sampling and participant recruitment, as well as using shared research instruments.

We carried out an online survey with 67 stakeholder participants in Iceland and 109 stakeholder participants in NL. This was followed up by one focus group of 8 of the survey participants in Iceland and three focus groups with a sub-set of 15 of the survey participants in NL. In their meta-analysis of literature on SDG interactions, Bennich et. al. (2020) note that the majority of SDG research is based on document analyses or conceptual modelling using scientific literature as data sources. They conclude that SDG research would benefit from more use of participatory methods (e.g., interviews, surveys, and focus groups) that draw on expert and stakeholder knowledge. Our study helps address this knowledge gap. Survey recruitment used a purposive sampling strategy. We focused on various “interested publics” in issues of public policy and sustainability (broadly defined). The sampling frame was constructed by all members of the research team, who bring a diversity of experience across several community engaged projects in these regions. Community partners also reviewed and elaborated the sampling frame.

Our participants reflect stakeholders across six sectors that were selected to represent a broad range of interests: academic (30% of participants in Iceland; 23% of participants in NL), business and industry (21% of participants in Iceland; 21% of participants in NL), government (7% of participants in Iceland; 8% of participants in NL), NGO (19% of participants in Iceland; 31% of participants in NL), union/labour (21% of participants in Iceland; 1% of participants in NL), and youth/students (2% of participants in Iceland; 14% of participants in NL). The same six sectors structured the sampling frames of all Sustainable Island Futures cases because they represent a spectrum of interested publics whose perceptions have the potential to influence SDG implementation in island jurisdictions (Randall, 2021).

Overall, survey and focus group participants are knowledgeable about economic, social, or environmental issues and debates in their respective regions. The majority of NL participants are over 40 years old (71%), while individuals over 54 years old account for almost half of NL participants (47%). There are slightly more male (56%) participants than female participants. All NL participants have received post-secondary or higher education, with a majority having completed a Master’s or PhD degree (63%). Most participants report their income as about the same or higher than the average in their community (88%). In Iceland, the majority of participants are over 40 years old (79%), with most individuals in the 40 to 54 age-group (45%). The majority of participants were male (63%). Most of the participants had received post-secondary or higher education, with a majority having completed a Master’s or PhD degree (91%). Most participants report their income as about the same or higher than the average in their community (84%). Our stakeholder samples tend to be middle aged or older, have more formal education, and represent higher-income groups than the general public in both societies. As such, they may hold different views about the SDGs, and sustainability issues more broadly, than the general publics of both societies. This is an important qualification. Because the sample is demographically non-representative of these regions’ populations, we do not generalize the results beyond the participants in this study.

Despite limitations in generalizability, the data provide valuable insight into how particularly interested publics from across key stakeholder groups perceive the various SDGs and dimensions of sustainability, as well as how they assess the role of government and other institutions in implementing the SDGs. By narrowing our attention to the six key stakeholder groups who play significant roles in shaping the discourse, policymaking, advocacy, or implementation efforts related to SDGs in the region, this study focuses on exploring the perspectives held by these groups. With cautious data interpretation, such a focus offers us a resource-efficient way to study interested publics’ perspectives that might be diluted in a more broadly representative sample. It would undoubtedly be beneficial to compare the views of our non-representative sample of stakeholder groups with a more representative sample of the general public to see whether and how views about the SDGs and their implementation differ. However, there remains much to be learned from the interpretations of the SDGs and their implementation among stakeholder groups that have clear interests in sustainability issues and debates. A similar approach to focusing on key stakeholder groups’ interpretations of the SDGs has been used in other contexts, including Quito, Ecuador (Horn & Grugel, 2018), as well as other cases of the Sustainable Island Futures project, such as the comparative analysis of Le Réunion and Mauritius (Tandrayen-Ragoobur et al., 2021).

Our survey instrument contained five sections. The first section focused on interpretations and assessments of various social and political institutions, including the government (national or provincial), civil service, municipal/local governments, police, and judiciary. This section also asked about provincial relationships with the national government (for NL), as well as international relationships. The second section asked participants for their assessments of the importance of each of the 17 SDGs, as well as their assessments of how well the region is doing in making progress towards each of the 17 SDGs. The third section asked participants about their own values and actions towards sustainability-oriented activities, as well as for their assessment of government performance on ensuring community sustainability. The fourth section focused on a suite of questions that delved more deeply into issues of economic sustainability. We chose to focus on economic sustainability because of the shared experience of financial crisis, including the 2008 Icelandic financial crisis and the ongoing financial crisis in NL. We singled out the economic dimension of sustainability to see whether our participants prioritize economic imperatives over other dimensions of sustainability. The final section asked for participants’ demographic information.

The third author assisted with analysing the survey data. We primarily focused on descriptive statistics of participants’ responses to survey questions. A significant qualification of our statistical data analysis is that we used a purposive, non-random sample that includes relatively small numbers within certain participant groups. This limits the possibilities for generalizing the results to these regions’ wider populations. We used the R likert package (Bryer & Speerschneider, 2016) to visualize the distribution of participant responses.

After the survey, we organized follow-up focus groups among a sub-set of our survey participants. Focus groups provided space to generate further qualitative insight into our survey findings by drawing on the “interactional expertise” (Nerini et al., 2019) generated through conversation among research participants. Of the Newfoundland survey participants, 34 agreed to be contacted and of these 15 participated in the focus groups. Of the Icelandic survey participants, 22 agreed to be contacted, while 8 participated in the focus group.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, focus groups were held online via Zoom and were co-moderated by the first and second authors for their regions, with support from other members of their respective research teams. Zoom is a “next-best” alternative to face-to-face participation compared to other digital or remote options (Archibald et al., 2019). While there may be challenges related to technical issues, Zoom has several advantages including: the ability to bring together geographically disparate research participants, accessibility, and reduced time requirements for research participants. Zoom features such as screen sharing and real-time file sharing are also benefits of the platform and may add to a sense of rapport with researchers (Archibald et al., 2019).

For the NL case, we held three focus group sessions, each lasting approximately 90 minutes. The first group included participants whose affiliations were with business, government, or unions/labour. The second and third focus group included participants whose affiliations were with academia, NGOs/civil society, or students/youth. In Iceland one focus group session was held that included participants whose affiliations were with all six stakeholders’ groups.

The focus groups were semi-structured, with open-ended guiding questions on the following topics: How participants assess the general performance of the government; the benefits (or not) of regional relationships with governments around the world; whether the physical environment of the region is being preserved in a responsible manner; participants’ assessments of regional progress towards the SDGs; and assessments of economic sustainability in the region and what might be done to ensure future economic sustainability. Narrative data on the linkages between how the SDGs are interpreted and how they are acted upon was provided by the discussion questions: What do you know about the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and what is your assessment of how Iceland/Newfoundland and Labrador has done in trying to meet these Sustainable Development Goals?

The focus groups were transcribed by a research assistant and inductively analysed by the first and second authors using NVIVO software for qualitative analysis. The coding scheme was structured around the following analytical categories: government performance; provincial-federal government relationships (for NL); regional-international relationships; views on protecting the physical environment; economic sustainability; and views on the SDGs and their implementation in the region. A semi-structured approach was used to manually code and inductively generate secondary thematic categories from the focus group data (Ryan & Bernard, 2003).

We used a qualitative comparison table to synthesize and compare results across cases (Iceland and Newfoundland) and data sources (surveys and focus groups) (see Stoddart et al., 2020). Qualitative comparison tables are structured by listing key analytical dimensions or considerations in the rows, with the different cases serving as columns. The cells are filled in with summary notes on the main findings for each data source by case as they speak to the various analytical dimensions. The final column provides space for filling in notes on comparisons and synthesis across cases. The qualitative comparison table was populated collaboratively by co-authors from the Iceland and Newfoundland research teams, with meetings held to discuss emerging findings and to refine the cross-case analysis.

Results

Participant interpretations of the SDGs

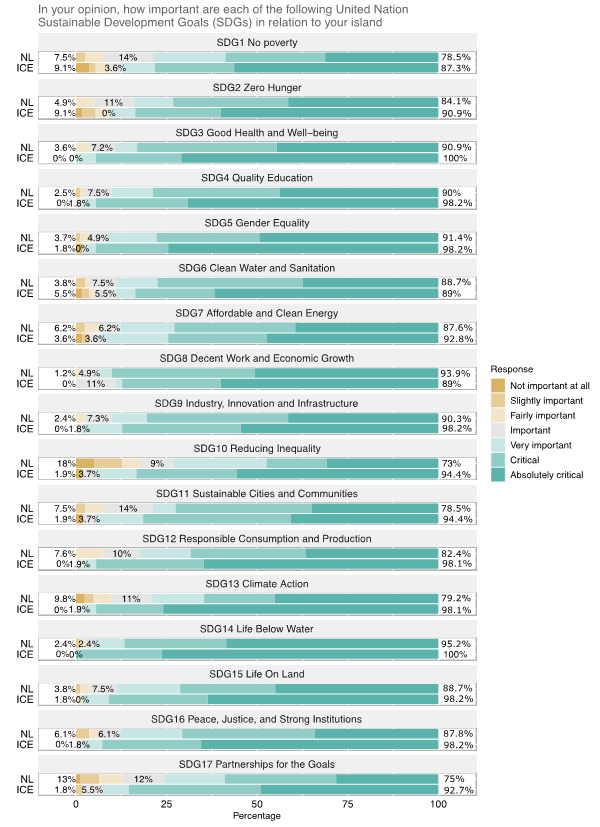

We begin this section by examining participants’ views of the SDGs in relation to ensuring sustainable futures for the islands of Iceland and Newfoundland. As Figure 1 illustrates, the majority of survey participants viewed all 17 of the SDGs as “very important, critical, or absolutely critical.” The SDG that has the highest salience across both study regions are SDG14: Life below Water, which was rated as “very important, critical, or absolutely critical” by 100% of Iceland participants and 95% of Newfoundland participants. This may reflect the cultural influence of islandness and how interpretations of the SDGs are shaped by living with and making a living from oceans, including fisheries and coastal tourism. Economically oriented SDGs — including SDG8: Decent Work and Economic Growth and SDG9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure — were also seen as “very important to absolutely critical” by most participants across both regions. Here, we see similarities across our study regions, including an emphasis on economically oriented SDGs, but not at the expense of other SDGs. Other SDGs that were nearly unanimously viewed (90% plus) as “very important, critical, or absolutely critical” by participants across both case studies include SDG4: Quality Education, as well as SDG5: Gender Equality.

There are some notable differences in how participants in the two regions assess the importance of the SDGs, including around SDG1: No Poverty, SDG10: Reducing Inequality; SDG11 Sustainable Cities and Communities; SDG13: Climate Action; and SDG17: Partnerships for the Goals. In each case, there is at least a 10% discrepancy across groups of participants, with the Newfoundland participants less inclined than Icelandic participants to rank these SDGs as “very important, critical, or absolutely critical.”

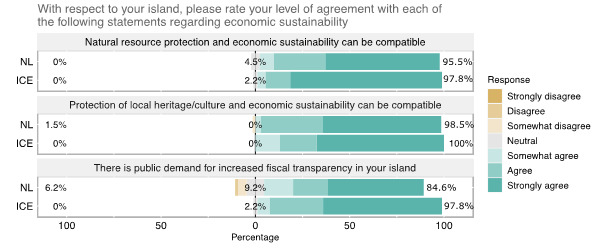

So far, we see that participants across both cases assert the importance of a broad range of SDGs, in which the economic oriented SDGs are valued but do not overshadow other SDGs. We also explicitly asked participants for their views and the compatibility of economic sustainability and other forms of sustainability (see Figure 2). Participants in both Iceland and Newfoundland were nearly unanimous in their views that economic sustainability can be compatible with natural resource protection, as well as the protection of local heritage and culture. Given that both Iceland and Newfoundland and Labrador have experienced financial crises, we also asked about whether participants perceive a public demand for increased fiscal transparency on their respective islands — a question that bridges economic and institutional/governance dimensions of sustainability. While most participants across both regions agreed or strongly agreed that there is public demand for greater fiscal transparency, this sentiment is notably stronger among Icelandic participants. These responses once again demonstrate a widely shared interpretation among participants that economic sustainability is a co-requisite with other dimensions of sustainability (environmental and social-cultural), rather than seeing economic sustainability as a trade-off against other dimensions.

Our focus groups add nuance to participants’ views of economic sustainability in relation to the SDGs. In our Iceland focus group, participants underlined that economic sustainability is largely non-existent in the current global economy, with economic systems based on consumption, rather than sustainability. Participants generally took a broad view about the need to rethink economic growth and focus more on economic balance, which requires a change of social values that take account of how Icelanders are impacting and damaging nature. For example, an especially critical participant asserted that because many Icelanders feel the country is already doing well, there is less self-reflection that might improve sustainability policies. In terms of building economic sustainability, notable themes include that Iceland could use a much larger part of the land-base for food production to diminish the need for food imports. Participants also asserted that it is important to give people more opportunities to be sustainable themselves, and to raise awareness to rein in rampant consumerism. There was also talk about Iceland’s economic dependence on the fishing industry and tourism, which are vulnerable to environmental change. From this perspective, achieving economic sustainability means that economic development cannot overstep the boundaries of the nation’s natural resources.

Our Newfoundland focus groups tend to focus on the current economic unsustainability of the province. Comments across our focus groups highlight the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric mega-project as a prime example of poor planning for economic sustainability. Other themes include that the province has lots of natural resources that are not as well used as they could be; that government has a track record of poor decision-making regarding support and investment to the private sector; and observations about the failure to secure a legacy fund from oil development in the province. Another recurrent comment is that there is lots of individualized wealth and economic success in NL, but this has not translated into economic sustainability for the province as a whole.

In comparing the focus groups and linking these themes back to the SDGs, we see that the Iceland focus groups tend to engage in broader critiques of consumerism and growth-oriented models of economic development. This interpretation of economic sustainability aligns more closely with SDG12: Responsible Consumption and Production. By contrast, the Newfoundland focus groups’ conversations about economic sustainability aligns more with SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure. As such, while participants in both regions emphasize the importance of economic sustainability — and are critical of how economic sustainability is implemented in their respective island societies — the specific ways in which economic sustainability is conceptualized show important differences.

Governance for SDG implementation

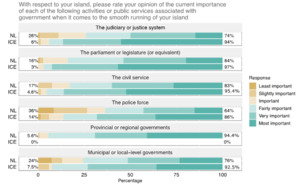

When looking at key stakeholders’ interpretations of the SDGs, a key question is which agencies or institutions bear the responsibility for translating the SDGs into policy and practice. This question relates to SDG16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions and SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals, both of which speak to the fundamental issue of governance for translating and implementing the SDGs. In this section, we turn to perceptions of the roles of government and other public institutions for building and ensuring sustainability. Participants were asked to indicate the perceived importance of six public institutions: the national parliament or legislature, provincial or regional government, municipal and local governments, the civil service, the judiciary, and the police (see Figure 3). Across both our cases, government actors were seen as most important. However, there are differences of scale. Icelandic participants indicated the national parliament as the most important of these public institutions, with 97% of participants rating the national parliament as “fairly, very, or most important.” Similarly, 94% of Newfoundland participants viewed the provincial government as “fairly, very or, most important” to ensuring the smooth operation of their respective island societies. Note that Iceland has a two-level system of government that does not have a provincial/regional scale in between the national and municipal levels. As such, there is no data for the provincial or regional government item for the Icelandic case for Figures 3 and 4.

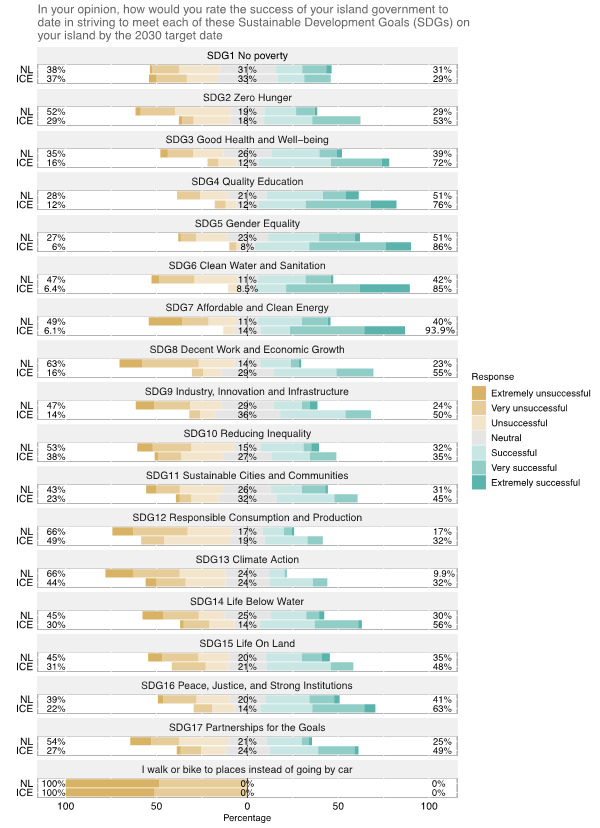

Going further, as Figure 4 illustrates, both cases show similar gaps between the perceived high importance of government institutions, on one hand, and critical views of governmental performance. This gap is substantially more pronounced in the Newfoundland case. Dissatisfaction with the national parliament was expressed by 32% of Icelandic participants. Among Newfoundland participants, 65% expressed dissatisfaction with the provincial government.

Figure 5 focuses on participant assessments of governmental performance on each of the 17 SDGs. Overall, Icelandic participants view their government as successful in making progress on most of the SDGs. Sizeable majorities of participants rated government action as successful particularly in the areas of SDG5: Gender Equality (86%), SDG6: Clean Water and Sanitation (85%), SDG7: Affordable and Clean Energy (80%), and SDG4: Quality Education (76%). Conversely, Icelandic participants are most critical of government on SDG12: Responsible Consumption and Production (59% rated as unsuccessful) and on SDG 13: Climate Action (44% rated as unsuccessful). By contrast, Newfoundland participants express less positive assessments of government action across most of the SDGs. The most positively evaluated SDGs in terms of government success were SDG4: Quality Education (51%) and SDG5: Gender Equality (51%). These were the only SDGs where a small majority of participants believed the government has been successful in making progress. Conversely, Newfoundland participants were particularly critical of government on SDG12: Responsible Consumption and Production (66% rated as unsuccessful), SDG13: Climate Action (66% rated as unsuccessful), SDG8: Decent Work and Economic Growth (63% rated as unsuccessful), SDG17: Partnerships for the Goals (54% rated as unsuccessful), SDG10: Reducing Inequality (53% rated as unsuccessful), and SDG2: Zero Hunger (52% rated as unsuccessful). Notably, although Newfoundland participants are generally more critical of government performance, there are several areas of overlap across cases in the goals that were singled out for positive assessments of government performance (Gender Equality and Quality Education), as well as those singled out for negative assessments of government performance (Responsible Consumption and Production and Climate Action).

Finally, we turn to our focus groups to elaborate our quantitative survey findings about governance for translating the SDGs and implementing sustainability. In response to questions about implementing sustainability, many focus group participants expressed dissatisfaction with Iceland’s performance. Illustrative examples from participants included the lack of local food production, as well as the slow pace of shifting away from fossil-fuel oriented transportation and supporting the expansion of public transportation. Focus group participants also noted that Iceland is far from doing enough to preserve nature and the environment in a responsible manner. For example, participants noted the difficulties in creating a central highlands national park to ensure the protection of nature from the potential negative impacts of traffic and over-tourism. However, participants also noted an “awakening” within the tourism sector towards using locally sourced materials and ingredients as a response to market demand.

Participants also pointed out that Iceland was ranked 26th in a recent report on the SDGs, which is not a strong performance. Participants, however, noted that the SDG framework is still relatively new and there is a need to expand information about the SDGs through public communication. Participants agreed that the SDGs are a guiding light for society and noted that there could be courses for educating companies, organizations, and professional associations on implementing the SDGs into policy and practice. The overall view from participants is that greater attention should be devoted to communication and awareness raising about the SDGs.

Participants further noted the inconsistency of measures when it comes to climate issues or biodiversity. Municipalities have inconsistent measures and standards, so there is a need for a more centralised state approach to these and other sustainability issues (which resonates with SDG16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). However, the Icelandic government was harshly criticized for its climate stance during the period 1995 until 2020, when it justified rising greenhouse gas emissions in the name of global climate governance by allowing emissions to increase from aluminium plants in Iceland under the rationale that it would ultimately lessen global emissions by displacing production from regions like China. Icelandic politics was also criticized for a lack of self-reflexivity when it comes to sustainability policies and performances. Relatedly, concerns were raised that the national government is not taking due consideration of economic status and class when formulating sustainability policy. Translating this into SDG terms, the concern is that sustainability policies are being pursued that risk amplifying, rather than reducing, social inequality as per SDG10: Reducing Inequality for All.

Yet, participants also noted signs of improvement on the horizon. Reflecting on political parties’ environmental policy before and after the 2017 elections, there appears to be a substantial difference. Part of the change has happened thanks to the impact of the Icelandic Youth Environmentalist Association and the ranking scale that was produced to rate political parties’ climate and environmental policies, which at least three political parties put real effort into following. Participants also note a significant difference between public opinion then and now in terms of greater public environmental awareness. This is helping to drive a shift in the political culture, rather than the shift coming from government itself.

Turning to the Newfoundland focus groups, the predominant theme is that the province is falling short on sustainability and has significant room for improvement. This is linked to critical discussion about waste management, forestry practices, lack of implementation of a protected areas plan, and failing to protect environmental infrastructure (such as the East Coast Trail, a well-known hiking trail that has substantial co-benefits as a tourism attractor for the province). Conversely, though less prevalent, multiple comments note that the government is doing a good job on environmental sustainability, with specific reference to the regulation of the oil sector as rigorous and adequate. Another notable theme that comes up is about the potential of the fishery as a sustainable core industry for the province.

When asked directly about the SDGs, the dominant recurring theme is that the provincial government is disengaged from the SDGs. From this perspective, any positive movements towards the SDGs are coincidental and not purposefully guided by the SDG framework. This is consistent with our Icelandic participants’ views that one of the main issues with the SDG framework is its lack of public and political visibility. Other recurring comments are that the province is doing poorly on achieving the SDGs. Access to clean drinking water, as per SDG6: Clean Water and Sanitation, is flagged as a particular area of poor performance. Participants note that many — particularly rural — communities in the province are subject to regular boil water advisories. By contrast, a less frequently expressed view is that Newfoundland and Labrador is doing well in achieving the SDGs in comparison to many other regions around the world.

Most of our participants offered critical assessments of the provincial government. Themes include that provincial government decisions are often based on political interests, rather than the public interest; and that there is generally a “poor quality” of politicians in the province (e.g., that it is difficult to recruit/elect “high-quality” candidates into office). These themes connect directly with SDG16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions. Other recurring critical comments highlight the lack of coordination across government departments; and that the province is falling behind on issues of climate change, decarbonization, and energy transitions (issues that relate to SDG13: Climate Action and SDG7: Affordable and Clean Energy).

However, this is balanced by some positive comments about the performance of the provincial government, most notably about the well-managed provincial response to COVID-19. Participants also recognize that the provincial government is working hard with limited resources, and that there is a positive trend towards greater support for entrepreneurship and innovation in the province (which aligns with SDG9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure).

Discussion and Conclusion

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a toolkit to translate the broad concept of sustainable development into policy and practice. However, to successfully translate the SDGs, we need to understand how they are interpreted by decision-makers, stakeholders, and publics at the regional and local scales (Bennich et al., 2020; Horn & Grugel, 2018; Szetey et al., 2021; Tandrayen-Ragoobur et al., 2021). We focused on interpretations of the SDGs in the unique context of island societies, focusing on the national island jurisdiction of Iceland and the subnational island jurisdiction of Newfoundland. We asked two main research questions: How do research participants — representing a range of stakeholders and attentive publics — interpret the SDGs in relation to ensuring sustainable futures for their island societies? How do participants view the roles of government and other institutions for translating sustainability (as per the SDGs) into policy and practice?

In relation to our first research question about interpretations of the SDGs, the goal with highest salience for participants is SDG14: Life Below Water, which likely reflects the special resonance of this goal for island and coastal societies that have close relationships with oceans for a range of social practices, cultural values and modes of economic development related to fisheries, tourism, or energy (also see Andrews et al., 2021; Nilsson et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2021). Participants also express near-unanimous support for a range of other goals including SDG4: Quality Education and SDG5: Gender Equality. As both Iceland and Newfoundland have grappled with financial crisis in recent years, we also expected to see high salience of economically oriented SDGs. As per our expectations, the economically oriented SDGs (SDG8: Decent Work and Economic Growth and SDG9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) are emphasized. However, economic sustainability is not prioritized at the expense of other SDGs. Most participants see the economic dimension of sustainability as compatible with protection of natural resources and local heritage and culture. This is consistent with research that describes co-benefits between the oceans goal (SDG14) and other SDGs (e.g., Grilli et al., 2021). However, as research on SDG trade-offs suggests, participants’ views of compatibility between the economic growth-oriented SDGs (SDG8 and SDG9) and other SDGs may be overly optimistic and ignore fundamental underlying tensions unless coastal development is pursued in ways that intentionally aim to “tightly couple environment, society, and economy” (Singh et al., 2018, p. 229). Interpretations of the meaning of economic sustainability are also notably different across cases. Icelandic participants define economic sustainability in ways that are more aligned with SDG12: Responsible Consumption and Production, while Newfoundland participants define economic sustainability in ways that align more with SDG9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure. So, even though there are similar overarching patterns across the cases, there are also important nuances in how the SDGs are interpreted as locally relevant and meaningful.

In relation to our second research question about the role of governments and other institutions in implementing the SDGs, participants across both cases view government as the most important institution, with Icelandic participants pointing to the national parliament and Newfoundland participants pointing to the provincial government. Despite the difference in political scale, our results show a gap between perceiving government institutions as highly important for implementing sustainability and high levels of dissatisfaction with those same institutions (though reported dissatisfaction is higher in the Newfoundland case). The interpretation of government as an especially important actor for implementing the SDGs, coupled with a highly critical view of government performance on ensuring sustainability, is consistent with findings from Russell et al. (2021) and Tandrayen-Ragoobur et al. (2021). These findings point to the importance of SDG16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions as a foundation for ensuring successful translation of the other SDGs. Furthermore, participants in both cases see mixed records of success in implementing the SDGs and are especially critical on implementation of SDG12: Responsible Consumption and Production and SDG13: Climate Action. In order to rectify the lack of performance on these SDGs, in particular, it may be necessary to highlight potential “win-win” solutions (Tàbara et al., 2020) and develop “transformative narratives” (Hinkel et al., 2020) that demonstrate the synergies and co-benefits between SDG12 or SDG13 and the SDGs that already have greater traction among decision-makers.

In answering these research questions, we also gain theoretical insight into a broader question about whether it is state versus subnational jurisdiction distinctions, or whether it is shared islandness and small polity dynamics that appear to explain the similarities and differences in how stakeholders and attentive publics interpret the Sustainable Development Goals and the roles of government and other institutions in implementing the SDGs. The key takeaway from our analysis is that participants’ interpretations of regionalizing/localizing the SDGs are surprisingly similar, despite the different national and subnational political and social contexts of Iceland and Newfoundland. While there are nuanced differences between the cases, the broad similarities give credence to the view that shared social-political dynamics of islandness and small polities are at play (e.g., as per Brinklow, 2013; Lévêque, 2020; Vézina, 2014). Further consideration should be given to how the particular characteristics of islandness and small policy dynamics work to facilitate or impede SDG implementation.

There appear to be common underlying social factors related to small polity dynamics and islandness that create important contexts for how the SDGs are interpreted at the regional or local scale. However, we should not be too quick to throw out the national versus subnational island distinction. As an island nation, Iceland enjoys differences in government capacity, resources, and international connectivity that can open greater possibilities for SDG implementation. Conversely, as a subnational jurisdiction, Newfoundland and Labrador often depends on the political mediation of the federal government, which can be a hindrance for sub-national island jurisdictions (also see Stoddart et al., 2021).

We close with limitations and directions for further research. First, our survey and focus group participants come from a non-random sample of key stakeholders representing government, business, labour, civil society, academia, and youth/students. As such, we do not attempt to generalize our findings to the general publics of Iceland or Newfoundland and Labrador. A key direction of further research would be to carry out additional waves of survey data collection and focus groups, using the same research instruments, with a more representative sample of the general public.

Second, this is a paired comparison across two cases of the broader Sustainable Island Futures project. This paired comparison across island nations and subnational island jurisdictions in an intentional part of the project design. This allows us to identify key similarities and differences in SDG interpretations in islands that share important social-cultural or geographic similarities, while offering the different political contexts of island nations and subnational island jurisdictions. All twelve cases of the broader Sustainable Island Futures project are subject to similar paired comparisons. However, a key direction for further developing this research program is to extend the findings generated through paired comparisons through further comparisons and synthesis across a greater number of island societies. Extending this analysis to a broader range of cases would enable us to further test and validate the degree to which islandness and small polity dynamics underlie interpretations about the local/regional relevance and implementation of the SDGs in national and subnational island jurisdictions.